Introduction

The definition of homelessness has been long discussed, and the different delimitation used by distinct authors is responsible for some of the heterogeneity between published articles studying this population.Reference Fazel, Khosla, Doll and Geddes 1 , Reference Hossain, Sultana and Tasnim 2

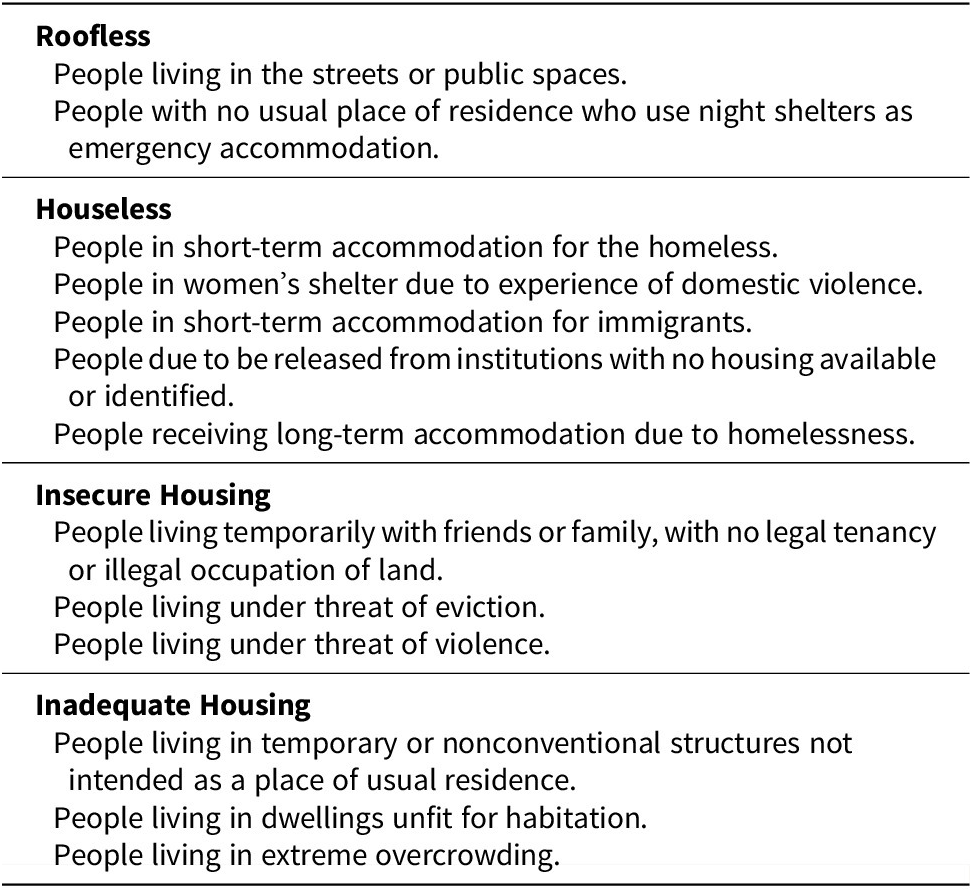

According to the European Typology of Homelessness and Housing Exclusion (ETHOS), there are four main categories of people that are included in the homeless definition: the roofless, the houseless, the ones with insecure housing, and the ones with inadequate housing (see Box 1). 3

Box 1. Homeless Definition Adapted from ETHOS (FEANTSA, 2005)

Abbreviations: ETHOS, European Typology of Homelessness and Housing Exclusion; FEANTSA, Fédération Européenne d’Associations Nationales Travaillant avec les Sans-Abri.

Homeless people are inevitably more vulnerable due to their living conditions, with the mortality in this group up to five times higher than the rest of the population.Reference Fazel, Geddes and Kushel 4 This high mortality is associated with a higher incidence of infections, heart disease, accidents, homicide, suicide, substance misuse, with drug overdose being the leading cause of death among the people living homeless.Reference Fazel, Geddes and Kushel 4 – Reference Ventriglio, Mari and Bellomo 6

The substantial amount of psychiatric disorders in this population is well documented.Reference Fazel, Khosla, Doll and Geddes 1 , Reference Nielsen, Hjorthøj and Erlangsen 7 – Reference Schreiter, Bermpohl and Krausz 10 According to a systematic review, the most prevalent mental disorder among the homeless people, in western countries, was alcohol dependence (8.1%-58.5%), seconded by drug dependence (4.5%-54.2%), and psychotic disorders (2.8%-42.3%).Reference Fazel, Khosla, Doll and Geddes 1 There is also high suicidal ideation in this population: Desai et al indicated that half of their sample, of 7224 homeless people with mental illness, had attempted suicide.Reference Desai, Liu-Mares and Dausey 11 , Reference Bauer, Baggett and Stern 12

Mental illness is an independent risk factor for homelessness; single adults with a major mental illness have a 25% to 50% risk of homelessness over their lifetime.Reference Bauer, Baggett and Stern 12 – Reference Shelton, Taylor and Bonner 15 The burden of the mental health is preponderant among other known risks factors for becoming homeless, namely foster care experience and history of incarceration, and also among the known risks factors that reduce the chances of exiting homelessness, including psychotic disorders, and drug use problems.Reference Nilsson, Nordentoft and Hjorthøj 16 The struggle of navigation in the mental health system, due to disorganization and severity of mental illness, also reduces the chances of homelessness escape.Reference Foster, Gable and Buckley 17 Some studies reported that most homeless first experienced symptoms of mental disorders before their initial period of homelessness and that the ones who reported no symptoms were likely to develop them over time.Reference Winkleby and White 18 , Reference Muñoz, Vázquez and Koegel 19 The identification of specific patterns of homelessness in homeless people with mental illness led to the creation of different classifications. In 1979, Leach subdivided them into intrinsic, people living homeless due to mental or physical disability; and extrinsic, people living homeless due to situational factors.Reference Leach, Wing and Olsen 20 , Reference Bhugra 21 In 1984, Arce and Vergare subdivided them into chronically homeless, predominantly older and with mental illness; episodically homeless, younger people who alternate between housing and institutional care, and life on the streets; and transiently homeless, people without identified major mental illness that got homeless due to an acute situational crisis.Reference Fazel, Geddes and Kushel 4 , Reference Arce, Vergare and Lamb 22 , Reference Kuhn and Culhane 23

Within the marginalized group of the homeless people with mental illness, there is an even more vulnerable group, the homeless people with dual diagnosis, that is, the homeless with a major psychiatric disorder plus a substance use disorder. Dual diagnosis people are overrepresented in the homeless population and are characterized by social isolation, including from support networks, having more difficulty accessing basic support like healthcare.Reference Schütz, Choi and Jae Song 24 , Reference Fischer and Breakey 25

In general, the contact of this population with the healthcare system is via the emergency department, using it more often and at higher rates than nonhomeless people.Reference Salhi, White and Pitts 26 The search for medical care often comes in cases of acute somatic crises, with the ones with mental illness among the group of people living homeless who use more health services.Reference Kaduszkiewicz, Bochon and van den Bussche 27 , Reference Bonin, Fournier and Blais 28 Despite the great prevalence of mental disorders in this population, there is a paucity of motivation among the homeless people to seek psychiatric treatment, and the ones who seek it often use the emergency department as their main source for psychiatric help, a place where there is no time and conditions to deal with the homeless people’s complex problems.Reference Kaduszkiewicz, Bochon and van den Bussche 27 , Reference North 29 , Reference Padgett 30 This disproportionate use of the emergency departments is an indicator of suboptimal utilization of primary care.Reference Bauer, Baggett and Stern 12 , Reference O’Neill, Casey and Minton 31

The people living homeless are more frequently hospitalized than the general population, for both medical and psychiatric reasons, and have a 45% increase in the length of psychiatric hospitalization stay, comparing with the nonhomeless psychiatric inpatients.Reference Bauer, Baggett and Stern 12 , Reference Tulloch, Khondoker and Fearon 32

This pattern of healthcare use, notably delayed presentations for medical attention, high emergency department reliance, high rates of hospitalization and extended length of hospital stays, and the overall poor health of the homeless leads to increased healthcare costs.Reference Bauer, Baggett and Stern 12 , Reference Salit, Kuhn and Hartz 33

Examining Portugal’s situation, there have been informal reports of mental illness afflicting the wanderers of Lisboa, the capital and major city, for almost 100 years.Reference Cebola 34 Unfortunately, these were the times when people living homeless could be nicknamed as vagabonds and other equivalent pejorative designations in our country.

More recently, in one night during 2009, in Portugal, 2133 people were identified as homeless. 35 In 2015, in Lisboa, there were 818 people sleeping rough (roofless) or in overnight shelters (houseless). 36 In 2013, the Portuguese homeless people, in Lisboa, were mostly men (88.6%), mostly aged between 35 and 64 years old (68%), and only a few less than half (44%) had no Portuguese nationality. 36 Concerning the mental illness, a study of 2002, again in Lisboa, pointed to a worrying prevalence of 96% of psychiatric diagnoses among a sample of 1000 homeless people.Reference Cruz, Bento and Barreto 37

The multiple problems that the people living homeless recurrently present and the categorization of them as off-limits or distracting makes their treatment perceived as demotivating among the health workers, the so-called “difficult patients” or even “super difficult patients.”Reference Padgett 30 , Reference Carnot and Gama Marques 38 , Reference Barreto, Bento and Luigi 39 A good example of the complex problems psychiatrists have to deal with on a daily basis was published as a case report, by one of the authors, describing one particular super difficult patient, living as homeless, with 85 hospital admissions in a 25-year span.Reference Gama Marques 40

Healthcare usage by homeless people remains a challenge worldwide, a truly composite problem that led to the proposition, by some authors, that homeless people with mental illness should become the object of Marontology, a new medical specialty, named after the Greek word marontos, which means unwanted.Reference Gama Marques and Bento 41

The study of the national homeless population is fundamental to the understanding of a phenomenon conditioned by the social picture of each country, providing the national social and health services a better source for policy implementation, allowing a more evidence-based approach targeting the well-being of the homeless.Reference Aldridge, Story and Hwang 42 Considering the lack of updated research concerning the mental health problems of the homeless population in Portugal, our main goal with the present study was to explore the demographic and clinical profile of the homeless people with mental illness living in Lisboa, Portugal, in particular those living in primary homelessness (ie, roofless) and secondary homelessness (ie, houseless), according to the ETHOS. 3

Methods

Study design, setting, and participants

We used a cross-sectional design, collecting data for 4 years (from January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2019) among people living homeless, in Lisboa, Portugal, that were referred to our psychiatric hospital team at Centro Hospitalar Psiquiátrico de Lisboa (CHPL) as possible homeless people with mental illness by the town hall social bureau workers at Câmara Municipal de Lisboa (CML). The contact with the homeless people occurred mostly on the streets, with our psychiatric hospital team reaching them at their usual place for sleeping. However, some homeless people were reached during appointments or during an open psychotherapeutic group, at CHPL, many times sent by other nongovernmental organizations. To be eligible, the homeless had to provide their full names and their date of birth, which we assembled into a preliminary Microsoft Excel document, either to the town hall social bureau workers, or to the psychiatric hospital team, so that these data could be cross-checked with our CHPL hospital electronic database, looking for patient matches and the respective records. The electronic hospital archive had a 20-year range (from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2019), thus yielding a two-decade retrospective search. After the cross-check was performed, we proceed to data anonymization in the definite Microsoft Excel file. The confidentiality of the participants was completely assured by excluding all identification information into our final database file. Therefore, we felt no need in contacting the research ethics board of our hospital (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the participants.

Variables and data sources

This analysis explored clinical records from the CHPL database, a psychiatric hospital founded in 1942, previously known as Hospital Júlio de Matos, integrated in Portugal’s publicly funded healthcare. These records included sociodemographic (sex, age, nationality, city of origin if Portuguese, and usual place for sleeping), diagnostic, primary care registration (Centro de Saúde) and CHPL’s hospital admission information. We transcribed the clinical records from the CHPL database to Microsoft Excel 16.0, excluding all the patients’ identification information.

The mental disorders’ diagnoses were made according to the World Health Organization’s tenth edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), 43 and we separated these diagnoses into primary and secondary for a better assessment of the dual diagnosis burden in this population, using the respective diagnostic codes.

What we called primary diagnosis included the main psychiatric diagnoses, with obvious hierarchy importance, as classically included in the Axis I of the fourth edition of the American Psychiatry Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR). 44 This includes diagnoses such as other mental disorders due to known physiological condition (organic psychosis; ICD-10 F06), schizophrenia (ICD-10 F20), schizoaffective disorders (ICD-10 F25), unspecified psychosis not due to a substance or known physiological condition (ICD-10 F29), bipolar affective disorder (ICD-10 F31), recurrent depressive disorder (ICD-10 F33), and acute stress reaction (ICD-10 F43).

The secondary diagnosis regarded comorbid psychiatric disorders, with less hierarchy importance, such as alcohol and drug abuse, usually essential for the dual diagnosis category, and/or the ones classically included in the DSM-IV-TR 44 second axis (mental retardation and personality disorders). Here, we included mental and behavioral disorders due to use of alcohol (ICD-10 F10), mental and behavioral disorders due to multiple drug use and use of other psychoactive substances (ICD-10 F19), unspecified disorder of adult personality and behavior (ICD-10 F69), and unspecified mental retardation (ICD-10 F79).

Whenever a patient had only a diagnosis included in the secondary diagnosis group, it was considered as his/her primary diagnosis, for example, if a patient had a single diagnosis of ICD-10 Diagnosis Code F10, then alcoholism was considered his/her primary (and unique) diagnosis.

Our dependent variables were the number and duration of total psychiatric hospitalizations at CHPL, and the total years of follow-up at CHPL, based on the length of time between the first and last contact with CHPL.

Statistical methods

The sample of this study was characterized by descriptive statistics including mean with standard deviation and median with interquartile range for continuous variables, and frequency with percentage for categorical variables.

To test the hypothesis that there would be one or more mean differences (MDs) in the length of follow-up between the different primary psychiatric diagnoses, we used a Welch’s t-test, followed by a Games–Howell’s post hoc test. To test the hypothesis that the higher the number of psychiatric diagnoses, the higher the years of follow-up, we used another Welch’s t-test, followed by a Games–Howell’s post hoc test. To test the hypothesis that multiple psychiatric diagnoses were associated with statistically significant longer lengths of follow-up, we performed a nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test.

To test the hypothesis that the homeless with primary care registration had a higher number of psychiatric diagnoses, we conducted a nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test. To test the hypothesis that the Portuguese homeless had a higher number of psychiatric diagnoses, we executed another Mann–Whitney U test.

To test the hypotheses that there would be one or more MDs in the number, as well as in the duration, of psychiatric hospitalizations between the different primary psychiatric diagnoses, we used two Welch’s t-tests, followed by two Games–Howell’s post hoc tests. Finally, to test the hypothesis that multiple psychiatric diagnoses were associated with statistically significantly higher and longer psychiatric hospitalizations, a nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was performed.

We chose an alpha level of P ≤ .05 to report significance for the estimated parameters.

We used IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM Corp. Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) to conduct these analyses with professional supervision.

Results

Of the 500 individuals living houseless or roofless, in Lisboa, Portugal, referred to our team as possible homeless people with mental illness, 467 (93%) had already a clinical record at our hospital (see Table 1). Thus, we excluded from further analysis the remaining 33 (7%) homeless people without clinical records in our archive. Our sample of 467 homeless psychiatric patients was predominantly male (77%), with a mean age of 46.16 years (standard deviation [SD] = 12.82). Mostly were Portuguese (59%), born from Lisboa (68%). The foreigners (41%) were from 52 different countries. The most represented foreign countries were Angola (17%), Iran (8%), and Guinea-Bissau (8%).

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Our Sample of 467 Homeless Psychiatric Patients

Abbreviation: n, number.

The most significant places for sleeping rough, in Lisboa, were the parishes of Arroios (21%), Misericórdia (16%), and Santa Maria Maior (11%; see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Map of homeless’ usual place (parish) for sleeping rough in Lisboa.

Somatic disorders were present in 159 homeless (34%). The most prevalent somatic diagnosis category was neurologic (18%), and among this, the most prevalent diagnosis was dementia (64%). The percentage of the people living homeless registered in primary care (ie, Centro de Saúde) was 63%, being 73% of them Portuguese.

The most prevalent primary psychiatric disorder was acute stress reaction (ICD-10 F43; 23%), followed by mental disorders due to known physiological condition (ICD-10 F06; 17%), schizophrenia (ICD-10 F20; 15%), and unspecified psychosis (ICD-10 F29; 14%).

There were some differences in the psychiatric diagnoses’ prevalence between Portuguese and foreigner homeless people (see Figure 3). Of the 65 houseless homeless refugees (14%), 80% had a primary diagnosis of acute stress reaction (ICD-10 F43).

Figure 3. Prevalence of primary and secondary psychiatric disorders between the Portuguese and foreigner homeless.

Sixty two percent (291) of our patients had multiple diagnoses. The most prevalent secondary psychiatric disorder was drug abuse (ICD-10 F19; 34%), followed by alcohol abuse (ICD-10 F10; 33%) and personality disorder (ICD-10 F69; 24%; see Table 2). The most prevalent multiple diagnoses were the combinations of ICD-10 Diagnosis Code F06 + F10 (6%), ICD-10 Diagnosis Code F29 + F19 (4%), ICD-10 Diagnosis Code F25 + F10 + F19 + F69 (4%), and ICD-10 Diagnosis Code F33 + F10 (4%).

Table 2. Prevalence of Primary and Secondary Psychiatric Disorders in the Homeless

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; F06, other mental disorders due to known physiological condition (organic psychosis); F10, mental and behavioral disorders due to use of alcohol; F19, mental and behavioral disorders due to multiple drug use and use of other psychoactive substances; F20, schizophrenia; F25, schizoaffective disorders; F29, unspecified psychosis not due to a substance or known physiological condition; F31, bipolar affective disorder; F33, recurrent depressive disorder; F43, acute stress reaction; F69, unspecified disorder of adult personality and behavior; F79, unspecified mental retardation.

Of the 467 people living homeless with records at our hospital, more than half (56%), 260, had been admitted at our psychiatric wards. The participants had a median of 2.0 (interquartile range [IQR] 1.0, 6.8) psychiatric admissions and a median length of total psychiatric hospitalizations of 55.0 (IQR 23.0, 142.8) days.

The women (median [Mdn] = 5.50) and the Portuguese (Mdn = 8.00) had higher median years of follow-up. A Welch’s t-test demonstrated a statistically significant effect of the different psychiatric diagnoses in the length of follow-up, F(6, 37.41) = 12.91, P < .001. The Games–Howell’s post hoc analyses revealed that all the Diagnosis Code F25 post hoc mean comparisons were statistically significant (P < .001) and that two of the Diagnosis Code F20 post hoc mean comparisons were, as well, statistically significant (P < .05), namely the one with the Diagnosis Code F29 mean and the one with the Diagnosis Code F33 mean. That is, on average, the homeless people with schizoaffective disorders (ICD-10 F25) have longer follow-ups than the other homeless with mental illness, and the homeless people with schizophrenia have longer follow-ups than the homeless people with unspecified psychosis and also longer follow-ups than the ones with recurrent depression. Another Welch’s t-test showed a statistically significant effect of the number of psychiatric diagnoses in the length of follow-up, F(4, 28.75) = 11.07, P < .001. The post hoc analyses failed to prove the hypothesis that the higher the number of psychiatric diagnoses, the higher the number of years of follow-up, despite the fact that the mean of years of follow-up of our sample follows the increase in the number of psychiatric diagnoses. A Mann–Whitney U test revealed that the follow-up was longer for the homeless people with multiple diagnoses (Mdn = 7.00) than for the homeless with a single psychiatric diagnosis (Mdn = 1.00), U = 3795, z = −4.52, P < .0001 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Relation between the number of psychiatric diagnoses and the years of follow-up.

The number of diagnoses was higher for homeless people with primary care registration (Mdn = 2.00) than for the homeless people without a primary care registration (Mdn = 1.00), U = 14 471, z = −8.21, P < .0001 (see Table 3). The number of diagnoses was higher for the Portuguese homeless people (Mdn = 2.00) than for the foreign homeless people (Mdn = 1.00), U = 14 784, z = −8.65, P < .0001.

Table 3. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Homeless Who Use Healthcare

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; Mdn, median.

There was a statistically significant effect of the different primary psychiatric diagnoses in the number of hospitalizations, F(6, 45.21) = 6.83, P < .001, and in the duration of total psychiatric hospitalizations, F(6, 59.09) = 10.35, P < .001. A series of Games–Howell post hoc analyses were performed to examine individual MD comparisons across the number and duration of psychiatric hospitalizations and all seven primary psychiatric diagnoses codes (see Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4. Post Hoc (Games–Howell) Mean Comparisons of the Number and of the Total Duration of Hospitalization Between Different Primary Diagnosis

Abbreviations: F06, other mental disorders due to known physiological condition (organic psychosis); F10, mental and behavioral disorders due to use of alcohol; F19, mental and behavioral disorders due to multiple drug use and use of other psychoactive substances; F20, schizophrenia; F25, schizoaffective disorders; F29, unspecified psychosis not due to a substance or known physiological condition; F31, bipolar affective disorder; F33, recurrent depressive disorder; F43, acute stress reaction; F69, unspecified disorder of adult personality and behavior; F79, unspecified mental retardation; MD, mean difference.

a Statistically significant MD.

Table 5. Medians of Length of Follow-Up, of Number of Hospitalizations and of Duration of Total Hospitalizations, per Primary Psychiatric Diagnosis

Abbreviations: F06, other mental disorders due to known physiological condition (organic psychosis); F10, mental and behavioral disorders due to use of alcohol; F19, mental and behavioral disorders due to multiple drug use and use of other psychoactive substances; F20, schizophrenia; F25, schizoaffective disorders; F29, unspecified psychosis not due to a substance or known physiological condition; F31, bipolar affective disorder; F33, recurrent depressive disorder; F43, acute stress reaction; F69, unspecified disorder of adult personality and behavior; F79, unspecified mental retardation; Mdn, median; IQR, interquartile range.

The number of psychiatric hospitalizations was higher for the homeless people with multiple diagnoses (Mdn = 3.00) than the homeless people with a single diagnosis (Mdn = 1.00), U = 3106, z = −5.90, P < .0001, and that the duration of the psychiatric hospitalizations was longer for the homeless people with multiple diagnoses (Mdn = 71.00) than for the homeless people with a single diagnosis (Mdn = 34.00), U = 3990, z = −4.05, P < .0001.

Discussion

The sociodemographic features of our sample of mentally ill homeless were similar to the ones found in a study of 2013 that characterized Lisboa’s homeless population. Nevertheless, our sample had a lower prevalence of males (77% vs 89%) and foreigners (41% vs 44%). 36 The foreigners were mainly from the Portuguese-speaking African countries, representing 35% of our foreigner homeless. This high prevalence is related to the big migration movement from the Portuguese-speaking African countries toward Portugal, mainly due to historical and cultural connections. Nonetheless, our sample only included 1% of Brazilian foreign homeless, despite the great prevalence of Brazilian immigrants (22% of the immigrants in Portugal). 36 , Reference Reis Oliveira and Gomes 45 These data suggest that the lower socioeconomic status and race of the immigrants of the Portuguese-speaking African countries can have some influence on their outcomes, as suggested before, stigmatized groups are more likely to become homeless, in particular those with minority racial or ethnic status, being overrepresented among homeless people.Reference Laporte, Vandentorren and Détrez 46 As for the second most prevalent foreigner nationality in our sample, the Iranian, were mainly houseless refugees or political asylum candidates, living in temporary shelters, usually provided by other governmental institutions (eg, Conselho Português para os Refugiados).

The most common psychiatric diagnosis in our sample of homeless people with mental illness was drug abuse (34%), followed by alcohol abuse (33%), personality disorder (24%), and acute stress reaction (23%). The acute stress reaction diagnosis was more prevalent in foreigner homeless due to 80% diagnosis of acute stress reaction in the refugees, mostly post-traumatic stress disorder. This was consistent with the literature, as several studies indicated alcohol and drug dependence as the most prevalent psychiatric disorders among the homeless.Reference Fazel, Khosla, Doll and Geddes 1 , Reference Schreiter, Bermpohl and Krausz 10 , Reference Fekadu, Hanlon and Gebre-Eyesus 47 , Reference Yim, Leung and Chan 48 Despite these similarities, there is a lack of diagnosis classification uniformity between studies and little or no reference to organic psychiatric disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder.

The diagnosis of organic psychosis (ICD-10 Diagnosis Code F06) was higher in our sample (17%) than in previous studies, probably because we believe extreme caution is recommended when diagnosing patients with severe psychotic symptoms, independently of their acute or chronic condition, as many different medical conditions are able to mimic functional psychosis such as schizophrenia, already nicknamed as the great imitated.Reference Gama Marques and Bento 49 , Reference Gama Marques 50 On the other hand, the higher prevalence of schizoaffective disorder (ICD-10 Diagnosis Code F25; 11%) might be explained by our theoretical background that perceives schizophrenia, and related disorders, as a broad spectrum.Reference Gama Marques and Ouakinin 51

There was a high prevalence of psychotic disorders in our sample: F06 organic psychosis (17%), F20 schizophrenia (15%), F29 psychosis not otherwise specified (14%), and F25 schizoaffective disorder (11%), that combined altogether were present in more than half (57%) of our homeless patients. These results are higher than a meta-analysis, conducted in 2019, that points to a prevalence of 29% of psychosis and 22% of schizophrenia in developing countries, and 19% of psychosis and 9% of schizophrenia in developed countries, among the homeless.Reference Ayano, Tesfaw and Shumet 52 Our psychiatric diagnosis prevalence may be higher due to our sample of mentally ill homeless, comparing with the broader sample of homeless people in most studies.

Sixty-two percent of our patients had multiple diagnoses, a close number to the described 55% prevalence of dual diagnoses, although previous studies usually conceptualize dual diagnosis as the combination of a primary psychiatric disorder plus alcohol or drug abuse.Reference Schütz, Choi and Jae Song 24 The number of diagnoses was higher for the Portuguese homeless people and for the homeless people with primary care registration, suggesting that closer contact and facilitated national healthcare engagement can promote medical diagnosis. Patients with multiple diagnoses had longer follow-ups, more psychiatric hospitalizations, and longer psychiatric hospitalizations than the homeless people with a single diagnosis. These findings are accordingly to the evidence that homeless people with dual diagnoses attend more primary healthcare services and emergency departments, have longer hospital stays, and have poorer psychological health.Reference Ding, Yang and Cheng 53 – Reference Khan 55

Of the seven primary psychiatric diagnoses included in our sample, the homeless people with schizoaffective disorder had statistically significant longer follow-ups, a higher median of psychiatric hospitalizations, and a higher median duration of total psychiatric hospitalizations. Despite these findings, the homeless people with schizoaffective disorder did not have a coherent statistically significant difference in the number and duration of hospitalizations compared with the other primary psychiatric diagnosis. These findings differ from older ones by Russolillo et al, who concluded that schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were the main predictors of hospital admission and length of stay.Reference Russolillo, Moniruzzaman and Parpouchi 56

Caution should be taken in the interpretation of these findings, since they do not apply to the general population of homeless people. Our initial sample of 500 people included only homeless people with suspected mental illness.

This study’s sample excluded the mentally ill homeless who had no contact with the workers of Lisboa’s city hall bureau or with the CHPL psychiatric team, potentially excluding the John Does, such as homeless people with severe mental illness but without registered identity. These are indeed the super difficult patients, in theory, the end-of-the-line of psychiatry care, and we acknowledge having failed to include them in our study.Reference Carnot and Gama Marques 38 Just as an example, we would like to remember one patient of ours, living as homeless for more than two decades, that has been admitted in our ward, and has stayed with us, for more than 2 years, and still is a John Doe, after all identification efforts from competent authorities.Reference Gama Marques and Bento 57

Despite the homeless 93% match in our hospital’s database, we cannot assume that the excluded ones do not have mental illness, since the data obtained were limited to our psychiatric hospital records and these homeless can have medical files in other hospitals.

Primary care registration was not a reliable indicator of primary care attendance. We are all aware that, in the last decades, the “worried well” had easier access to mental health care than the “suffering sick.”Reference Fuller Torrey 58

The somatic diagnoses are probably underestimated due to the deficient registration of these conditions by psychiatrists in the patient’s clinical electronic records.

When analyzing the psychiatric hospitalizations’ determinants, we did not consider that the homeless with worse social support usually have longer hospitalizations due to difficulties in hospital discharge.

Conclusion

The greater challenges in the homeless people with mental illness treatment are legislative, with lack of legislation regarding the homeless disabled by their mental disease who refuse treatment, and lack of coordination between health and social workers.Reference Bento and Barreto 59 Nonetheless, deciding to intervene while balancing patient autonomy and the principle of beneficence involves much skill and experience.Reference Yim, Leung and Chan 48

Future research is needed regarding the homeless people with mental illness and their treatment, particularly the ones with multiple diagnoses, a subgroup with a high burden of mental illness, and worse determinants of health. It would be interesting to study the homeless with a primary psychiatric diagnosis plus an addiction disorder plus a personality disorder. Therefore, we recommend the use of the most recent classification by World Health Organization, the ICD-11 classification, by researchers in further studies to improve research heterogeneity. 60

A follow-up of the patients that did not have a match at our hospital’s database would be interesting for checking development of psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. In the future, we hope to perform a longitudinal study of follow-up with our full sample for better understanding of this phenomenon. For better retrospective and prospective research, and better health care delivery, we recommend electronic medical record implementation at centers caring for homeless people. Research has demonstrated its suitability and effectiveness in the homeless population, allowing better care coordination, outreach, follow-up, and assessment of outcomes.Reference Blewett, Barnett and Chueh 61 – 64

Finally, after realizing the high prevalence of personality disorders among homeless people with mental illness, we are now interested in continuing previous studies regarding attachment disorder in the homeless population.Reference Leach, Wing and Olsen 20 , Reference Stefanidis, Pennbridge and MacKenzie 65 – Reference Rodríguez-Pellejero and Núñez 67 In the future, we hope to be able to study potential biomarkers candidates and/or risk factors for homelessness, such as oxytocin, an hormone that has been already proposed as having an interesting correlation with attachment styles.Reference Buchheim, Heinrichs and George 68

Last but not least, we also propose ourselves to keep working with the open psychotherapeutic group, as it seems to be an open door for easy referral and free of charge psychiatric care for the homeless population in our city.Reference Bento and Guedes Silva 69

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Paulo Nogueira, from Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Lisboa, for assistance with the statistics. They would also like to thank Mrs. Laurinda Carona and Mrs. Carmo Duarte, from Biblioteca, Santa Casa da Misericórdia de Lisboa, for help with the bibliography.

Funding Statement

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Disclosure

The authors do not have anything to disclose.