Are We Getting Our Money’s Worth Treating Serious Mental Illness as a Crime?

U.S. health care costs are staggering, with spending at $3.5 trillion dollars in 2017.Reference Martin, Hartman, Washington and Catlin 1 Additionally, criminal justice system expenditures are estimated at $270 billion dollars. 2 Our nation’s most at-risk individuals are falling through the cracks and entering a vicious cycle of incarceration and temporary institutionalization, which only exacerbates these costs.

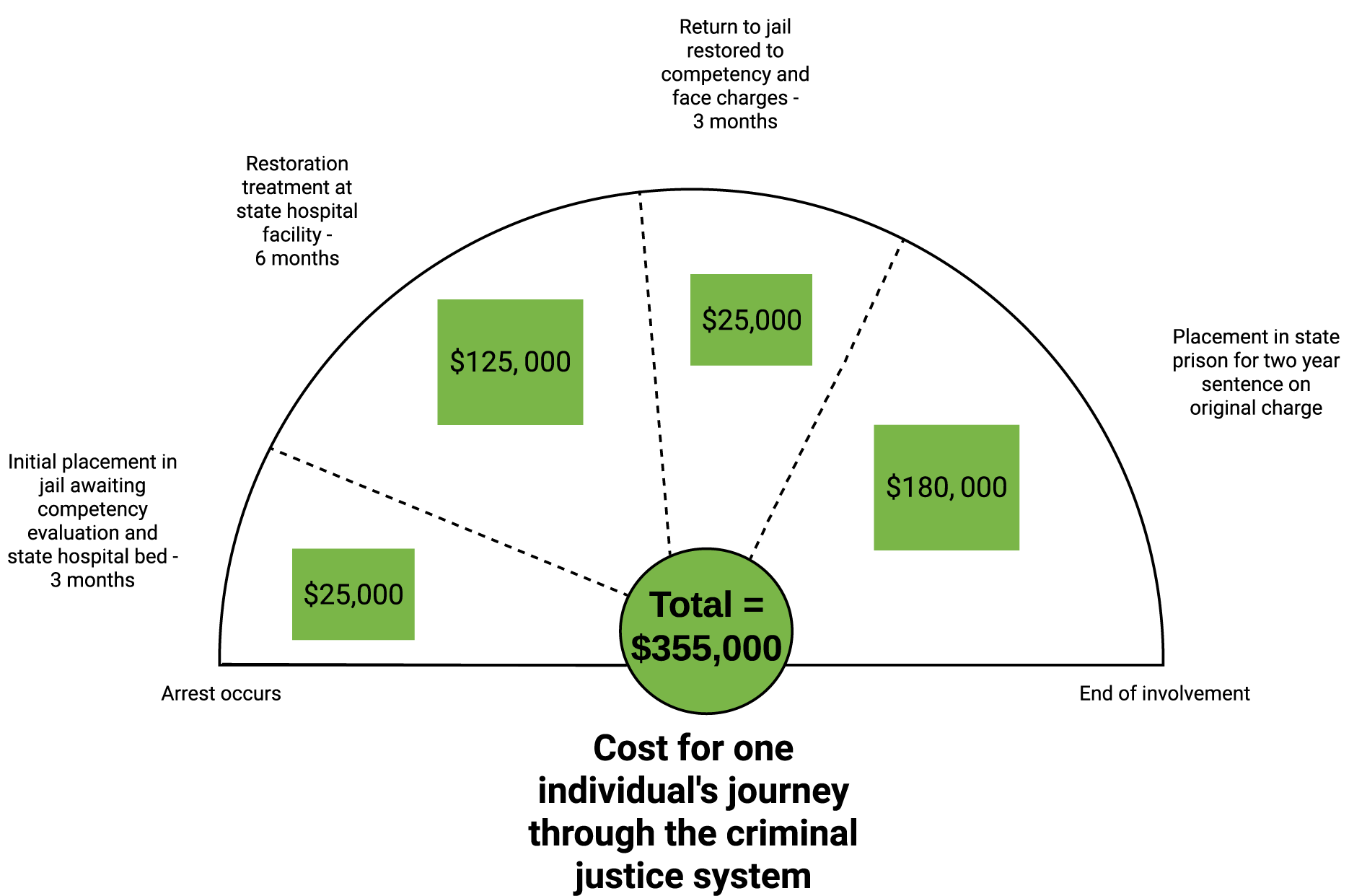

In Figure 1, the movement of a person through the criminal justice system is represented by squares for each institution or system that provides an individual with mental health treatment and include: county jail, state hospital, and prison. Within each of these institutions, costs for mental health treatment are staggering (Table 1). Estimates place jail treatment for individuals with mental illness at anywhere from $33 000 to $168 000 dollars per person per year nationally.Reference Giliberti 3 , Reference Salas 4 Additionally, once placed in state hospital treatment this cost increases to an average of $242 000 per patient per year in the United States (Email correspondence, S. Melching, 4/10/2019).Reference Lutterman, Shaw, Fisher and Manderscheid 5 The cost of a subsequent placement in state prison depends on whether an individual’s mental health treatment necessitates outpatient or inpatient treatment. The former costs are noted at approximately $80 000 to $100 000 per inmate per year while the range increases substantially if inpatient mental health treatment is required: $300 000 to $550 000 per inmate per year (email correspondence, L. Koushmaro, 8/30/2018). Even with utilizing the most conservative numbers, an individual who commits a crime, undergoes competency restoration, and serves a 2-year prison sentence will cost taxpayers somewhere in the range of $342 000 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1. Cycle of the criminal justice system for a person with mental illness.

TABLE 1. Cost of treatment per person per year.

FIGURE 2. Example of estimated cost of one individual’s journey through the criminal justice system.

Doing Well (for the Budget) While Doing Good (for the Forensic Patient)

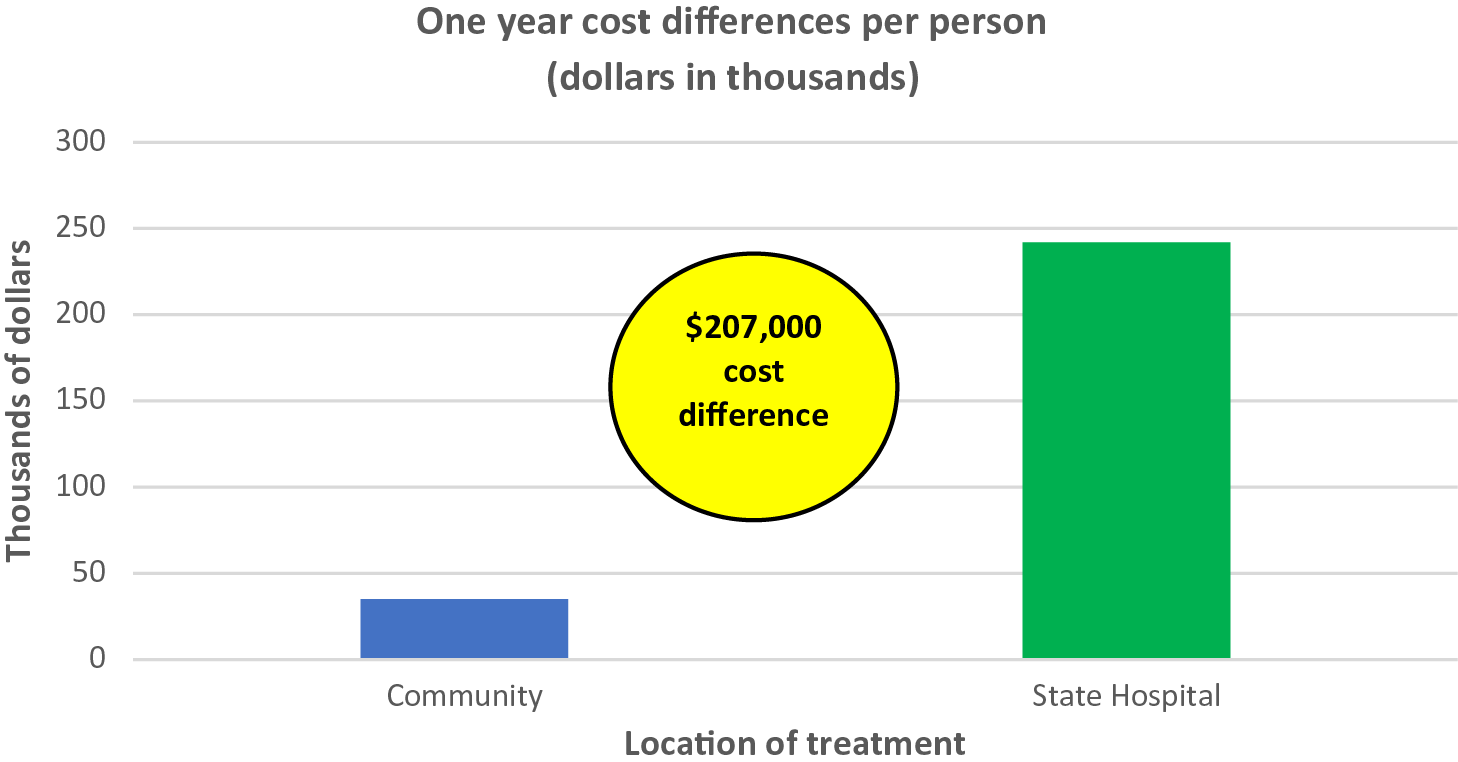

While these economic costs become astronomical when multiplying by the massive number of people who travel through the criminal justice system, the potential for change and fiscal improvement is equally considerable. The Sequential Intercept Model (SIM; Figure 3) conceptualizes how systemic interventions can break this cycle.Reference Munetz and Griffin 6 SIM provides a way for policies and programs to divert individuals out of the criminal justice system and into mental health treatment, long-term housing, and overall stability. Initial studies show promising cost-savings when implementing diversion programs.Reference Cowell, Hinde, Broner and Aldridge 7 , Reference Broner, Mayrl and Landsberg 8 As shown in Table 1, the annual cost of providing mental health treatment and housing to a person in the community ranges anywhere from $35 000 to $47 333.Reference Giliberti 3 , 9 By successfully implementing diversion with even a small group of individuals, cost-savings could be significant. Two recent examples of the potential cost-savings of these programs to communities are in San Antonio, Texas and Miami, Florida where diversion programs have saved taxpayers $10 million and $12 million per year, respectively.Reference Giliberti 3

FIGURE 3. Sequential Intercept Model.Reference Broner, Mayrl and Landsberg 8

Consider the potential fiscal outcomes of implementing mental health diversion programs across the United States. These hypothetical programs could specifically target individuals who, if not for an untreated or undertreated mental illness, would not be in jail. These individuals could receive treatment for their mental illness in the community, thereby breaking the cycle of inconsistent treatment providers across multiple systems (jails, prison, state hospitals).

Given these figures, conservative estimates can be drawn on the potential fiscal savings for implementing a mental health diversion program. Estimates of community mental health treatment costs indicate that mental health diversion would cost approximately $35 000 per person per year,Reference Giliberti 3 while a forensic state hospital bed in the United States averaged $242 000 per person per year.Reference Lutterman, Shaw, Fisher and Manderscheid 5 The mental health diversion of only one person could potentially save $207 000 (Figure 4). When including the estimated state costs of diversion participation to the annual cost of incarceration in a state prison for individuals with serious mental illnesses, the potential savings to the state are even greater Figure 5.

FIGURE 4. Prospective cost differences in 1 year of utilizing mental health diversion for 1 individual.

FIGURE 5. Prospective cost differences of state hospital treatment versus community diversion treatment.

A mental health diversion program would not have difficulty finding participants within the large cohort of individuals with mental illness in the criminal justice system; a recent studyReference Ochoa, Kim, Appel and Stephens 10 found that over half (56%) of the mental health population in a large U.S. jail system could be safely treated in the community if sufficient services were available. In 2016 alone, 13 734 individuals were admitted to state hospital beds around the country for competency.Reference Lutterman, Shaw, Fisher and Manderscheid 5 If even 50% of these individuals (half of the 13 734 individuals admitted = 6867 people) could have instead been diverted and safely treated in the community, with a cost savings of $207 000 each, the criminal justice system would have saved a staggering $1, 421, 469, 000 (Figure 5). Over $1.4 billion dollars saved, and as a bonus, individuals with mental illness receive the treatment they deserve—in the community.

Conclusions

Mental health diversion programs are a promising solution to the difficulties resulting from a combination of deinstitutionalization and state/federal funding cuts in the community behavioral healthcare system.Reference Miller 11 States across this country are grappling with the deluge of people suffering from serious mental illnesses who often have no recourse for their illness except incarceration. The costs of this public policy problem to taxpayers is enormous and is exponentially higher for the people who cannot access needed treatment and for their families, friends and communities. Diversion programs are an attempt to change that—to provide treatment resources in the community that stabilize these individuals, allow them to function effectively in society, and break the cycle of recidivation. Not only can diversion programs improve both criminal justice and mental health outcomes,Reference Hoff, Baranosky, Buchanan, Zonana and Rosenheck 12 , 13–15 it is a fiscally responsible way to provide much-needed mental health treatment to a vulnerable population. For diversion programs to be successful, adequate financial resources must be provided during implementation and sustainability phases. Repeating past failures in community-based mental health treatment can be avoided by the provision of fiscal support for diversion programs. Such support is an investment in the future, as broad estimates demonstrate the potential for a 1-year cost-savings of over $1.4 billion dollars from diverting treatment out of state hospitals and into the community.

Disclosures

Dr. Delgado, Ms. Breth, Ms. Hill, and Dr. Warburton have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Over the past 36 months, Dr. Stahl has served as a consultant to Acadia, Adamas, Alkermes, Allergan, Arbor Pharmaceutcials, AstraZeneca, Avanir, Axovant, Axsome, Biogen, Biomarin, Biopharma, Celgene, Concert, ClearView, DepoMed, Dey, EnVivo, EMD Serono, Ferring, Forest, Forum, Genomind, Innovative Science Solutions, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, Jazz, Lilly, Lundbeck, Merck, Neos, Novartis, Noveida, Orexigen, Otsuka, PamLabs, Perrigo, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Reviva, Servier, Shire, Sprout, Sunovion, Taisho, Takeda, Taliaz, Teva, Tonix, Trius, Vanda, Vertex, and Viforpharma; Dr. Stahl has been a board member of RCT Logic and Genomind; he has served on speakers bureaus for Acadia, Astra Zeneca, Dey Pharma, EnVivo, Eli Lilly, Forum, Genentech, Janssen, Lundbeck, Merck, Otsuka, PamLabs, Pfizer Israel, Servier, Sunovion, and Takeda and he has received research and/or grant support from Acadia, Alkermes, AssureX, Astra Zeneca, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Avanir, Axovant, Biogen, Braeburn Pharmaceuticals, BristolMyer Squibb, Celgene, CeNeRx, Cephalon, Dey, Eli Lilly, EnVivo, Forest, Forum, GenOmind, Glaxo Smith Kline, Intra-Cellular Therapies, ISSWSH, Janssen, JayMac, Jazz, Lundbeck, Merck, Mylan, Neurocrine, Neuronetics, Novartis, Otsuka, PamLabs, Pfizer, Reviva, Roche, Sepracor, Servier, Shire, Sprout, Sunovion, TMS NeuroHealth Centers, Takeda, Teva, Tonix, Vanda, Valeant, and Wyeth.