In 1956, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) conducted Japanese war crimes trials in Shenyang and Taiyuan. Six years earlier, the CCP had received 969 Japanese war crimes suspects, who had been extradited from the Soviet Union to Communist China, and detained them at the Fushun War Criminals Management Centre (Fushun zhanfan guanlisuo 抚顺战犯管理所), a detention facility in the People's Republic of China (PRC). The CCP also held in custody a group of Japanese servicemen who had fought on the side of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) against the CCP after the War of Resistance. Of these, 136 were regarded as serious war crimes offenders and were sent to the Taiyuan War Criminals Management Centre (Taiyuan zhanfan guanlisuo 太原战犯管理所) for war crimes and for fomenting counterrevolution - that is, for fighting against the CCP during the civil war.

What mattered most for the CCP was not necessarily administering justice and meting out punishment per se, but rather the process of reforming (gaizao 改造) these suspected Japanese war criminals and showcasing the effectiveness of their re-education about the criminality of their war crimes as well as the overall Japanese war of aggression. The war crimes trials constituted an important part of this reformation project.Footnote 1 During the CCP trials, only 45 war criminals were eventually brought to trial, while the rest were absolved of their war crimes and sent back to Japan in three waves between June and September 1956. The 45 former imperial officers were either of higher rank or were deemed to have carried out extremely heinous crimes. They stood trial in June and July 1956 and were sentenced to imprisonment for between eight and 20 years. No sentence of death or life imprisonment was passed down.

This paper examines accounts of sexual violence in the written confessions of Japanese war crimes suspects and the extent to which the CCP employed those accounts to prosecute the suspects during the trials. It first provides context for the CCP's legal approach to sexual violence by examining the coverage of cases involving rape and prostitution, with which the “comfort women” issue may have been associated owing to issues such as translation, in the People's Daily (Renmin ribao 人民日报), the Party's unofficial mouthpiece that targets a wide-ranging readership.Footnote 2 What is of interest here is that rape cases were frequently reported on alongside other crimes, and that the issue of prostitution was framed as a problem between brothel keepers and prostitutes, rather than between prostitutes and clients/foreign soldiers. This paper argues that the courts’ prosecutorial treatment was compatible with the contemporary discourse and state propaganda on legal decisions related to rape and prostitution as exhibited in the People's Daily. What then follows is, first, an examination of the written confessions of Japanese war crimes suspects, and second, an analysis of the CCP's prosecution of Japanese military servicemen for their acts of sexual violence against Chinese women in the 1956 war crimes trials. By contrasting representative descriptions of sexual violence in the confessions with the resulting indictments and judgments, it is shown that although accounts of both rape and comfort women can be found in the written confessions, the courts did not make rape a focal point of the prosecutions and did not pursue the so-called comfort women issue. Finally, the paper outlines probable reasons for this important discrepancy.

Existing literature concerning the CCP trials has explained the reasons and motivations for the magnanimous approach towards these suspected war criminals.Footnote 3 Marukawa Tetsushi and Barak Kushner have separately pointed out that the Japanese prisoners were dealt with humanely and received lenient punishment not only as a gesture of benevolence but also out of political considerations.Footnote 4 In the same vein, Ōsawa Takeshi has argued that the CCP viewed the war crimes suspects as “diplomatic cards” of high value during the early phase of the Cold War. Specifically, the CCP strove to secure a neutral stance towards Japan in the face of the US containment policy in the region.Footnote 5 Although unable to hold direct negotiations with the Japanese government, the CCP actively engaged with non-governmental agencies in Japan, arranging the repatriation of lesser war crimes suspects, in the hope of paving the way towards normalizing relations between the two countries.Footnote 6 Justin Jacobs has drawn attention to CCP efforts to prepare the Chinese people for a lenient handling of Japanese war crimes.Footnote 7 He points out that international developments such as the “Lucky Dragon incident,” which exposed Japanese fishermen to nuclear radiation in 1954, led to a change in PRC discourse on Japan, from vehement condemnation of Japanese wartime atrocities to a focus on cultural exchange activities. Following the deterioration in US–Japan relations in the aftermath of the Lucky Dragon incident, the CCP saw the war crimes trials as an opportunity to engage with Japan.Footnote 8 Through an analysis of diplomatic documents located in the PRC Foreign Ministry Archive, Adam Cathcart and Patricia Nash contend that the CCP's lenient policy towards Japanese detainees stood in stark contrast to its mass mobilization of Chinese citizens to report Japanese crimes in support of the Khabarovsk trials, in which the Soviet Union prosecuted Japan's use of bacteriological weapons in the former puppet state of Manchukuo 满洲国.Footnote 9 They, too, argue that the CCP trials were actually intended to usher in a new avenue of dialogue with Japan.Footnote 10 Separately, Adam Cathcart also examines the propaganda strategies employed by the CCP during the war crimes trials, demonstrating how the CCP strove to use Japanese war criminals to boost its image on the world stage.Footnote 11

However, scholarship related to the prosecution of crimes of sexual violence is relatively scarce. Arai Toshio, Kawada Fumiko and Ikō Toshiya have all separately shown that cases related to Japanese sexual violence surfaced in the war criminals’ confessions; Kawada in particular has analysed some of the sexual crimes mentioned in the confessions, based on the limited sources accessible in the 1990s.Footnote 12 With the declassification of the court records and the confessions written by the 45 war criminals prosecuted in the CCP trials, a comprehensive study of the treatment of sexual violence in the CCP trials has become possible: this paper attempts to address this under-researched topic and fill this academic lacuna. In 2005, the Central Archives of China (Zhongyang dang'anguan 中央档案馆) published these confessions in a ten-volume book series comprising a photocopied collection of records left by the 45 war criminals. The Chinese government later released 120 volumes of confessions in 2017, which were written by every Japanese war crimes suspect, including those exculpated in 1956, enabling scholars to comprehensively analyse various accounts manifested in the confessions. However, since the focus here is on the CCP's legal treatment of sexual violence, this paper limits its scope to the confessions of the 45 war criminals tried by the CCP.

Sexual Violence in the People's Daily

Before analysing the coverage of the CCP's legal approach to sexual violence in the People's Daily, it is necessary to provide an overview of the Party's legal statutes on rape. The CCP did not issue any laws on rape until the promulgation of the Penal Code in 1979. After founding the PRC, the CCP abolished all the codices previously implemented by the KMT but did not create new legal regulations and systems. This legal vacuum on civil and penal codes, however, did not mean that the CCP had no criminal regulations in place. It did publish three major acts stipulating the penalties for counterrevolution, corruption and activities that sabotaged the state currency.Footnote 13 Crimes such as rape, robbery and theft, along with some other serious offences, were absent from the published regulations.Footnote 14 Perpetrators of these offences were either tried in ad hoc people's trials with unknown standards, or in newly established judicial courts which adhered to a series of unpublished, confidential regulations circulated among the relevant personnel.Footnote 15 However, the unavailability of these documents renders it impossible to ascertain exactly how the CCP imposed penalties for rape and other sexual offences. The People's Daily, on the other hand, did report on rape cases from time to time, and can prove to be an alternative valuable source for understanding the CCP's legal approach to sexual violence. Equally important, unlike internal (neibu 内部) documents, the People's Daily has always enjoyed a wide readership. Its content can be said to reveal the way the CCP intended the general public to understand its legal approach. At the same time, with a legal discourse well established in the public sphere, the CCP's legal approach may have also been influenced or limited by the discursive norms regarding sexual violence.

The following examines the People's Daily coverage regarding the CCP's legal approaches to rape and prostitution, with which the comfort women issue may have been associated, from the founding of the People's Daily in 1946 to the commencement of the trials in 1956. Sexual violence is all too often politicized, whether in wartime or peacetime, but this section is not concerned with verifying the degree to which newspaper articles are based on facts or merely used for propaganda purposes. Instead, the purpose of the analysis here is to examine the representation of the CCP's legal treatment of sexual violence in the public sphere and to provide context for the Party's legal approach in the 1956 trials.

When a “well-to-do” student from Peking University was raped by US soldiers in December 1946, the People's Daily followed the case intensely. An article dated 12 February 1947 draws an analogy between Japanese crimes in the past and the American ones in the present, stating that even the Japanese had not dared to rape college students in the old capital of Beijing.Footnote 16 The emphasis on the victim's social status demonstrates a facile understanding of rape, as well as discrimination against rural and non-elite women, showing a tendency to downplay crimes against the latter group that was prevalent in Chinese society at the time.Footnote 17 The rape case triggered mass student demonstrations against the US military presence and American crimes in China, which received heavy coverage in the People's Daily. The two American perpetrators were first found guilty and then exonerated in a retrial. The People's Daily fervently denounced the Americans’ exculpation, regarding it to be an insult to the “honour and dignity of China.”Footnote 18 In this light, the People's Daily, whether intentionally or not, set a tone of condemning rape committed against Chinese women by foreign soldiers in the public sphere. With a discourse condemning foreign troops’ sex crimes well established, it now became more likely that the CCP would deal with these kinds of crimes in its own war crimes trials.

Later, articles in the People's Daily reported on a large number of sentences handed down to landlords, bandits and those labelled reactionaries during the “Campaign to suppress counterrevolutionaries” from 1950 to 1951, with rape being one of the charges. For example, on 23 May and 25 August 1951, the newspaper published long lists of court decisions rendered against defendants, some of which contain the crime of rape.Footnote 19 From March to May 1951, extensive coverage was given to crimes committed by KMT spies, landlords, bandits and those labelled reactionaries. Rape featured more than 40 times in articles published during this period, although it was frequently paired with other crimes, in the form of large numbers of people describing their bitterness and their recollections, and in the listing of punishments meted out to the perpetrators.Footnote 20 In this way, the consistent coverage of rape and legal decisions involving rape in the People's Daily communicated to the populace that the CCP regarded rape as a crime to be prosecuted and punished. Moreover, the pattern of mentioning rape in passing together with crimes labelled “reactionary” demonstrates that rape was worth mentioning only when it could contribute towards the goals of the Party's political campaigns. This pattern also set a precedent for the CCP's legal treatment of sexual crimes in the 1956 trials, as discussed below.

On the other hand, terms such as “enforced prostitution” (qiangzhi maiyin 强制卖淫) or “comfort women” (weianfu 慰安妇) do not appear in the People's Daily until years later. However, the Japanese terms for “comfort women” and “prostitutes” used by Japanese war criminals in their written confessions were translated as weianfu and jinü 妓女 (prostitutes) in Chinese. The newspaper's portrayal of “prostitutes” is therefore worth scrutinizing. In contrast to rape, which was mainly regarded as a crime committed against women by both foreign and domestic enemies in the past and present, prostitutes were primarily considered as victims of the “old society” in the People's Daily. Who, then, was to be held accountable for their sufferings?

The answer, in short, was that previous regimes in feudal societies were the culprits, and criminal responsibility was primarily attributed to brothel owners and pimps. An article dated 9 February 1950 notes that the old society and brothel owners were at the root of the suffering endured by prostitutes in the past.Footnote 21 In this same month, the People's Daily also reported on punishments handed down to brothel owners and pimps.Footnote 22 In the following two months, two other groups were also found guilty of running brothels and exploiting prostitutes.Footnote 23 Foreigners made appearances in the coverage on prostitution, but overwhelmingly as customers and rarely as the culprits forcing Chinese women into prostitution. As pointed out by Gail Hershatter, ever since the May Fourth movement, prostitution in China had been redefined and reconstructed “as an exploitative transaction,” with the exploitative relationship existing primarily “between the prostitute and her madam, not the prostitute and her customer.”Footnote 24 This logic corresponds to the media discourse and propaganda during the early 1950s. By upbraiding the KMT government and brothel keepers for prostitution, the People's Daily obscures other factors such as patriarchy, class and gender. The problem of prostitution was addressed in the Chinese public sphere by verbally condemning old society and by announcing the punishment of criminal procurers. The People's Daily therefore domesticated and localized the issue of prostitution together with the social problems associated with it. It was within this local discursive context that the CCP had the Japanese suspects write confessions. The Party then initiated the war crimes trials.

Sexual Violence in the Japanese Confessions

It is important to note that individual scholars still have limited access to the original manuscripts of confessions and copies of the court records. As a result, one may cast doubt upon the authenticity and veracity of such accounts. Scholars such as Marukawa Tetsushi, after talking to many of those suspected of war crimes, argues that it is hard to deny the psychological pressure exerted upon them, but he points out that such pressure exists in all societies to a certain degree.Footnote 25 James Dawes interviewed some of the Japanese detainees held by the CCP and also contends that the re-education project involved psychological coercion. However, he suggests that the detainees honestly recorded the crimes they perpetrated despite this coercion.Footnote 26 Importantly, we cannot ignore the fact that most of the CCP detainees continued to offer testimony against the excesses of war while calling for reconciliation between Japan and China upon their return to their homeland, where they had the chance to openly recant their confessions and denounce the CCP trials. The continuity in their post-war testimonies and activities give the confessions used in the CCP trials historical value.

The confessions were first collected in 1954, then rewritten and expanded up until the trials were held in 1956. The 45 Japanese war crimes suspects who eventually stood trial were divided into three groups for prosecution according to their military affiliation and activities in wartime China: higher-ranking military officers, Manchukuo officers, and those who fought for or worked for the KMT during the civil war. The first two groups were prosecuted in two cases in Shenyang, and the third group in two other cases in Taiyuan. The 28 Manchukuo officers, who were tried in one case in Shenyang, were high-profile officials. Their confessions primarily recounted details of the military operations of the puppet state. These included anti-espionage policies and the forced recruitment of local Chinese for construction projects. There were no specific references to wartime sexual violence, except for a brief mention of the comfort women system in the confession of Nakai Hisaji, who recounted his arrangements for constructing a house to be used as a military comfort station in Aihun 瑷珲, Heilongjiang province, at the behest of the Japanese military in May 1939.Footnote 27 The fact that this was the only link to sexual violence in the confessions of the 28 Manchukuo detainees in part explains why the CCP did not prosecute them for crimes of that nature. However, as Kumano Naoki has pointed out, the Kwantung Army was involved in the establishment and maintenance of comfort stations along the borderlands between Manchuria and the Soviet Union.Footnote 28 Mark Driscoll has also shed light on the massive scale of Manchukuo administrators’ participation in human trafficking and prostitution rings.Footnote 29 It is therefore highly probable that the officers prosecuted in the Shenyang trials were also directly or indirectly involved in sexual violence. The reason for their selective recounting of crimes cannot be determined, although Driscoll speculates that as human trafficking was so common in Manchukuo, female experiences did not particularly stand out. He also conjectures that, to some extent, Manchukuo itself had become a comfort station where human trafficking was taken for granted.Footnote 30 However, since the former Manchukuo officers, excluding Nakai, did not mention such crimes in their confessions, the present paper examines only the confessions written by the remaining 17 defendants accused of war crimes.

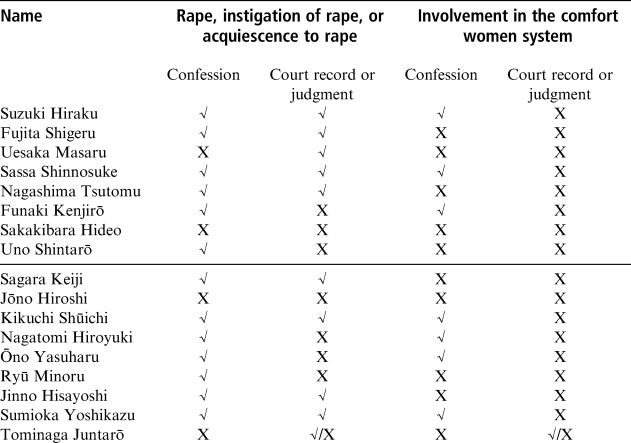

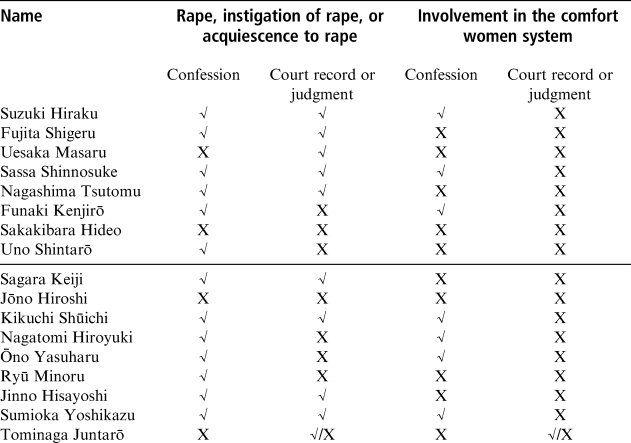

Among the 17 suspects tried in three cases in Shenyang and Taiyuan (separated by the line between Uno Shintarō and Sagara Keiji in Table 1), 13 confessed to sexual violence of one form or another, as noted in the columns designated “Confession” in Table 1; however, not all were prosecuted or mentioned in the final verdict, as illustrated in the columns designated “Court record or judgment.” In particular, the only mention of comfort women appears in the court record of Tominaga Juntarō, even though Tominaga did not mention any crimes of sexual violence in his confession. Instead, a witness named He Cheng 何澄 testified before the court that the military personnel under Tominaga's command raped women on many occasions. When asked by a judge how his Pacification Corps (xuanfuban 宣抚班) harmed Chinese on the battlefront or in areas already occupied by the Japanese military, Tominaga answered that, along with other crimes, his troops sent women to Japanese military comfort stations and raped them.Footnote 31 However, these crimes were not investigated further by the court and, as a result, Tominaga's sexual crimes did not figure in the final verdict.

Table 1: Statistics on Sexual Violence Recorded in Confessions and Dealt with in Courts

Notes:

√ – mentioned or treated; X – not mentioned or treated; √/X – mentioned before the court but not in the judgment.

From Tominaga's case and other examples, we can clearly see the emergence of a discrepancy between the confessions of sex crimes and the courts’ treatment of them as such. Owing to the abundance of information in these records, instead of examining all confessions, this paper focuses mainly on two case studies: Suzuki Hiraku and Kikuchi Shūichi, who were tried in the Shenyang and Taiyuan Special Military Courts, respectively. These accounts have been selected on the basis that they represent a comparatively well-rounded picture of sexual violence against Chinese women. Descriptions of other war criminals’ confessions are also incorporated as supplemental evidence wherever needed.

Suzuki Hiraku was a lieutenant general of the 117th Division of the Imperial Japanese Army when he was taken as a prisoner of war (POW) by the advancing Soviet army. He confessed in writing to acquiescence to rape, the establishment of comfort stations and the abduction of women. Suzuki mentions a case involving a mass raping spree. The Japanese troops under his command raped more than 100 women in a village named Lujiayu 鲁家峪, located in Hebei province, after a manoeuvre to mop up the Eighth Route Army, the military force under CCP command.Footnote 32 Suzuki's confession does not indicate whether he was personally involved in these egregious acts against women. By confessing to his role in this mass assault, however, one thing is certain: Suzuki, as chief of the 27th Infantry Brigade, considered himself to be accountable for the atrocities committed by his subordinates.

In terms of the comfort women system, his account is more substantive. Under the same military title of chief of the 27th Infantry Brigade, he issued a command to install comfort stations in places where Japanese military units were stationed, and instigated the abduction of 60 Chinese women for sexual service.Footnote 33 In addition, in a subsection entitled, “Crimes committed during the period of being commander of the 67th Infantry Regiment,” Suzuki describes ordering his adjutant, Major Horio, to set up a comfort station and how he had 20 Chinese and Korean women abducted to serve as comfort women.Footnote 34 When Suzuki was commander of the 4th Brigade of the 117th Division, he gave orders to establish comfort stations in all areas garrisoned by Japanese troops and to abduct around 60 Chinese and Korean women to act as comfort women.Footnote 35 In a separate document supplementing his written confession, Suzuki admitted that “when he received the order to transfer from Xinxiang 新乡 to the north-east in July 1945, he took five Japanese women from Xinxiang to Taonan 洮南 in the north-east.” He listed this under his category of “crime of abducting women.”Footnote 36 Similar accounts such as acquiescence to rape and involvement in the comfort women system are also found in other high-profile officers’ confessions, such as that of Sassa Shinnosuke, who served as commander of the 39th Division at the time of his arrest.Footnote 37 What the accounts of Suzuki and others spell out is the large extent to which they, as commanders of the Japanese military in various parts of China, were involved in the comfort women system as they gave orders for the establishment of comfort stations and the abduction of Chinese, Korean and Japanese women.

Towards the end of his confession, Suzuki refers again to his crimes of sexual violence:

For the purpose of the invading army, I set up the so-called comfort stations and had Chinese and Korean women abducted to serve as so-called comfort women. These abducted women wept while parting with their families. This situation brings into my mind the misfortune that befell Japanese women at that moment [after the war]. For the sake of survival, unfortunate Japanese women had to sell their bodies to the enemy Americans while shedding tears. Every time I think of how anguished the Chinese women must have been for selling their bodies to the invaders, I realize the gravity of my own crime. Also, how heart-wrenching it must have been for the husbands and families of those who were raped. Thinking of the wrath I felt towards the Americans who committed barbaric acts in Japan, I then understood how outraged the Chinese people must have felt about Japanese atrocities and how grievous my crimes were.Footnote 38

In the same section of his written confession, Suzuki narrates that upon watching Konketsuji (Mixed Race Kids, 1953), a movie about the unfortunate fate of a child of a black GI and a Japanese woman, he further comprehended the severity of his crimes.Footnote 39 It is not surprising that the Chinese detention centres showed the Japanese inmates films on the topic of occupation crimes and contemporary social problems resulting from the US occupation of Japan (1945–1952). The CCP propaganda was extremely critical of the US occupation, particularly after the so-called “reverse course” in which the priority of the US occupation policymakers switched from democratization and demilitarization to the reconstruction of the Japanese economy. The CCP denounced this policy shift as a US attempt to colonize Japan and rebuild the former enemy into a bulwark against the newly emergent Communist China.Footnote 40 Films of this kind were apparently intended to arouse a sense of empathy in their targeted audiences, compelling them to draw an analogy between American crimes in Japan and Japanese atrocities in China. Suzuki's reflection on sexual violence nevertheless fails to acknowledge the fact that prostitution as a livelihood in the post-war era was not the same as abduction for enforced prostitution during wartime. Furthermore, Suzuki's acknowledgement of sexual crimes is not entirely grounded in sympathy for the female victims. His self-reflection focuses largely on the sorrow he felt towards the families of the violated and the disgrace brought upon the nation as a result of its women being forced into having sexual intercourse with its enemies; there is little mention of the physical and psychological scars inflicted upon the female victims. Scholars elsewhere have pointed out that women's bodies have been made to embody the nation and its sovereignty, and thus sexual assaults inflicted upon them represent both men's failure to protect “their” women and the national humiliation of the conquered.Footnote 41 Suzuki's line of thinking, unfortunately, has once again become dominant in contemporary discussions on the comfort women issue, as some of the reparation movements and commemoration activities are politically and emotionally charged.Footnote 42 Japan's comfort women system is too easily associated with the national shame brought to the victims' countries, and thus politically galvanized nationalist causes sometimes take precedence over the healing of women's physical and psychological pain.Footnote 43 For Suzuki, national shame was highlighted, while individual victims’ experience, agency and trauma were downplayed.

Kikuchi Shūichi, a major general when he was captured by the CCP, confessed to multiple rapes and the establishment of comfort stations. As his accounts of sexual violence are far more detailed than those of Suzuki, only the most representative excerpts are examined here. Kikuchi writes that, between July 1938 and September 1945, he committed 57 instances of rape, according to his own estimation.Footnote 44 In most of these instances, he committed the crimes with either the assistance of Chinese interpreters employed by his troops or the Security Corps (baoandui 保安队), which was a collaborationist force made up entirely of Chinese nationals.Footnote 45 For example, on one day in June 1943, at 22:00, Kikuchi intimidated the company commander of the Security Corps, Li Yongqing 李永清, into guiding him to the home of a 16-year-old girl who was raped on the scene. Later, Kikuchi states that he raped this same girl three more times.Footnote 46 The interpreter's dwelling also became a place where Kikuchi raped other women who he ordered to be brought there, and it appears that it served not only as a raping station on a singular basis but also as an incarceration cell in which women were imprisoned for the purpose of multiple rapes, most likely over a span of several days. For instance, on a day in late March 1942, at 22:00, Kikuchi gave orders to the interpreter to bring to his house a 19-year-old woman, whom he later raped eight times.Footnote 47 Chinese women were not only confined to a place where they were repeatedly raped but also were at times coerced into accompanying Kikuchi as sex slaves. For example, in May 1940, he raped a woman when he was a contingent commander and thereafter sexually assaulted the same woman more than 20 times in Wuzhaicheng 五寨城 and Shenchicheng 神池城.Footnote 48 These multiple incidents of sexual violence against the same people in different locations indicate that these victims must have been detained by Kikuchi. Both the women made to accompany Kikuchi and those who were detained in a given location were evidently sex slaves, and the crimes Kikuchi confessed to ought to be considered as the sexual enslavement of women.

Kikuchi's confession is quite detailed, and information such as the exact date and time of day is recorded along with other confessed crimes including murder and looting. It is remarkable that Kikuchi's recollections of his crimes are so precise. Because he died in 1979, it is impossible to interview him about the veracity of his statements.Footnote 49 The detailed nature of his confession might have been in response to CCP pressures to recount his crimes in as much detail as possible. Whatever the reason, Kikuchi, like the other detainees, never denied the authenticity of his confession or denounced the CCP trials after he returned to Japan.

Kikuchi's acts of violence against women continued, albeit to a lesser extent, even after Japan's surrender. His confession indicates that from September 1945 to April 1949, when he was fighting on behalf of the KMT, he raped four women, one of whom was raped twice and another five times.Footnote 50 In addition to these incidents of rape, Kikuchi was also proactively engaged in setting up comfort stations for Japanese soldiers and officers who had agreed to stay in China and fight for the KMT. In late March 1948, at his suggestion, his corps paid 100 bags of wheat for a comfort station originally managed by the Sixth Corps of the Japanese Army. After some repairs, the new managers recommenced activities at the comfort station. Six Chinese comfort women were confined there.Footnote 51 This episode unambiguously demonstrates the involvement of Kikuchi, a Japanese military officer, in the establishment and operation of comfort stations, similar to Suzuki's confession noted above. It is unclear how these Chinese women were procured. However, it is clear that Chinese women were subjected to sexual violence by Japanese perpetrators between 1945 and 1949, after the end of the War of Resistance. Kikuchi's account suggests that the end of the war did not put a halt to the fear of abduction, enslavement and rape commonly shared by Chinese women at that time, at least not in Shanxi province, where Japanese servicemen remained.

Indictments and Verdicts: The CCP Trials, Reconsidered

The CCP trials were conducted expeditiously in Shenyang and Taiyuan from June to July 1956. The trials deliberately aimed at guaranteeing fair-trial protection, as the court assigned lawyers to war crimes suspects and granted the defendants the right to question witnesses and to defend themselves. As all the war crimes suspects had admitted to the crimes listed in the indictment and pleaded guilty as charged, there was no process of cross-examination in court. Therefore, instead of serving as a forum for prosecutors to provide a detailed case against a particular defendant, the trials focused on hearing cases from victims and witnesses, and having the defendants acknowledge their crimes and apologize in open court. The trials functioned to some extent as a stage on which to demonstrate the purported achievements of the CCP's re-education programme.Footnote 52 The performative nature of the trials thus informs the following investigation of the ways in which incidents relating to sexual violence were dealt with in the CCP trials. The examination below focuses on the legal proceedings against Suzuki and Kikuchi, who were tried in Shenyang and Taiyuan, respectively.

The indictments list chronologically the crimes the defendants committed. Each paragraph details atrocities perpetrated during a certain military manoeuvre in which the Japanese defendants were involved, or during a particular period in which the defendants were deployed at a particular military outpost in China. Overall, the judgments bear a remarkable resemblance to the indictments, as all the defendants acknowledged their crimes and readily pleaded guilty, with some supplementary testimonies heard before the court. In Suzuki's case, his crimes were substantiated by 181 letters of accusation from victims and relatives of victims, 45 testimonies from witnesses, 89 inquiry transcripts, one investigation report, 33 photographs, one copy of a Manchukuo newspaper and his confession.Footnote 53

Among the crimes committed in Lujiayu, the village Suzuki mentioned in his written confession where more than 100 women were sexually violated, the indictment details the case of Qian Lianfa 钱连发, who stated that his 18-year-old daughter was gang-raped to death after being poisoned by gas. The indictment also mentions the case of Liu Qinglong 刘清隆, who testified that his wife was burned to death after being raped.Footnote 54 Unlike Suzuki's confession, in which the large number of victims (more than 100) was discussed, the prosecution identified two victims of rape. Moreover, these descriptions are the only record of sexual violence found in Suzuki's indictment. The indictment was substantiated by a witness named Zhang Junjin 张俊金 who appeared before the court. Zhou Shuen 周树恩, another eyewitness who testified to the slaughter that occurred in Panjiadaizhuang 潘家戴庄 in Hebei province, where Suzuki's troops were stationed, also referred to the Japanese servicemen's mass sexual assault against Chinese women. He stated that the Japanese rounded up 100 young women and drove them to a large yard. There, they proceeded to rape and gang-rape these women, one of whom was his wife.Footnote 55

The sexual atrocities described in Zhou Shuen's testimony were not included in Suzuki's confession, but were included in the final judgment, because Suzuki confirmed the authenticity of this testimony during the trial. The concluding paragraph of the final judgment reads:

Based on the facts listed above, this court confirms that the defendant Suzuki Hiraku, during the period in which he participated in the imperialist war of aggression against China, committed the following crimes: executing a war of aggression; violating international law and humanitarian law; ordering troops under his control to create depopulated zones, to destroy towns and villages, and to expel non-belligerents; slaughtering and torturing non-combatants; looting and destroying property; releasing poisonous gas; forcing civilians into military labour; and conniving for his subordinates to rape women.Footnote 56

Suzuki was sentenced to 20 years of imprisonment on the charges recorded above. As the CCP trials did not break down the penalty handed out for each crime, we cannot ascertain exactly how much weight was given to sexual violence in the final deliberation of judgment.

Kikuchi's indictment was substantiated by 60 letters from victims and relatives of victims, 35 testimonies from witnesses, six investigation reports and his own written confession. Kikuchi was also charged for his post-war crimes in Taiyuan.Footnote 57 Despite the extensive accounts of sexual violence recorded in Kikuchi's confession, the only mention of them in the final indictment was that, “based on the accusation letters from victims […] and the defendant's former underlings […] from March 1944 to March 1945, the defendant […] raped and acquiesced to his subordinates raping women.”Footnote 58 Regarding these particular atrocities, the judge asked Kikuchi whether the charges that he had raped and connived for his subordinates to rape women were true or not. The answer was in the affirmative.Footnote 59 The final paragraph of the judgment passed down to Kikuchi reads:

Based on the facts listed above, this court confirms that the defendant Kikuchi Shūichi, during the period in which he participated in the imperialist war of aggression against China, committed the following crimes: violating international law and humanitarian law; ordering troops under his control to kill civilians and POWs; looting, burning, and destroying property; and raping women. After Japan's surrender, he committed the crimes of organizing the Japanese military to participate in Yan Xishan's 阎锡山 army; initiating anti-revolutionary arms; undermining the Chinese people's liberation war; plotting to revive Japanese militarism; killing POWs; looting; and destroying property.Footnote 60

Kikuchi was sentenced to 13 years for these crimes. The atrocities committed by Kikuchi against Chinese women after the War of Resistance were entirely absent from either the court proceedings or the judgment. This signals that the suffering forced upon Chinese women was understood to be secondary to the crime of fighting on behalf of the KMT.

The CCP trials as a whole, as illustrated by the Suzuki and Kikuchi cases and as shown in Table 1, did indeed hold war crimes suspects accountable for the rape of Chinese women. This is substantiated by the fact that rape was mentioned in both the indictments and the witnesses’ testimony heard before the court, which were included in the final judgments. It is noteworthy that the prosecution indicted these men for the crime of sexual violence. It is also worth noting that the court examined accusations of rape against Uesaka Masaru, who was found guilty of the crime in one of the Shenyang trials, despite a complete absence of any record relating to sexual violence in his written confession (see Table 1). The court examination and final judgments elucidate the CCP's willingness to deal with rape charges as long as there was sufficient evidence to substantiate the accusation. However, mentioned only in passing alongside other crimes, rape never became a focal point of the CCP's prosecution. Kikuchi's extensive accounts of the various incidents of rape in which he was involved were condensed into a single sentence in the court proceedings. Furthermore, no rape victims were called to testify before the court. As stated above, one of the objectives of the CCP trials was to hear from the victims and witnesses and to make it possible for the defendants to give an apology and express remorse.Footnote 61 Indeed, the victims and witnesses of many other crimes had their voices heard in this legal, public forum, but not the rape victims, whose suffering went unacknowledged in the public domain.

Except in the case of Tominaga Juntarō, the comfort women system did not figure in the court proceedings, despite 7 of the 17 – or 8 of the 45 if the case involving 28 top-level Manchukuo officials is included – war crimes suspects describing related activities in their confessions (see Table 1). Meanwhile, the legal negligence over the comfort women issue strongly suggests that the confessions of the war crimes suspects on this issue at least were not forced; if the CCP regarded the operation of comfort stations as a war crime and forced the Japanese detainees to confess to it, it would have dealt with the comfort women issue in the legal proceedings. It is difficult to ascertain the exact reasons underlying such a prosecutorial omission, but a few well-founded speculations may be made here.

First, the prosecutors might have encountered difficulties in building a case against the comfort women system, since it raised many questions regarding the evidentiary value of the personal accounts in the written confessions. The CCP trials strove to ensure the fairness of the trials and to make sure that all the crimes prosecuted were substantiated. Without other verifiable evidence, the confessions alone may not have been deemed sufficient to make a strong case in court. Furthermore, it was generally very difficult for female victims to attest to the sexual violence inflicted upon them, fearing further marginalization by China's patriarchal society.

Second, both the words chosen for the confessions and for the Chinese translations obscured the cruelty and coercion of the comfort station system. The detainees’ confessions were written in Japanese and then translated into Chinese for the purposes of the court. Some suspects used the Japanese word ianjo 慰安所 for comfort stations, while others such as Funaki Kenjirō, Ōno Yasuharu, Sassa Shinnosuke and Nakai Hisaji also used yūkaku 遊郭, gikan 妓館, shunya 春屋 and girō 妓楼, respectively, all of which denote brothels of different types.Footnote 62 The different terms used for comfort stations of various types to some extent support Sarah Soh's argument that there existed a wide range of Japanese comfort stations, and their functions and operational nature varied over time and across physical locations. Based on her study on Korean comfort women, she maintains that both commercial sex and sexual crimes took place in comfort stations.Footnote 63 Fujime Yuki, on the other hand, fundamentally questions the so-called commercial sex industry of Japan's pre-war state-regulated prostitution system, which she considers to have been a system of sexual slavery that placed women under constant surveillance by the state and subjected them to violence. She further argues that the wartime comfort women system amounted to a militarized, intensified and deteriorated version of the pre-war licenced prostitution.Footnote 64 Adding Chinese experience to the picture, Peipei Qiu and Su Zhiliang contend that what happened to the great majority of Chinese comfort women in various comfort stations constitutes sexual slavery.Footnote 65 The purpose of the discussion here is neither to establish a hierarchy among comfort women victims nor to conflate all comfort stations into one category, but to demonstrate that the variety of the terms used by the war criminals points to the existence of comfort stations of multiple types under a system that exploited women's bodies and sexuality. In fact, as Ueno Chizuko has pointed out, even for the comfort stations that went by the same name of ianjo and the slave-like conditions to which female victims were subjected, historical context and circumstances matter in our understanding of the comfort women system and the experiences of female victims.Footnote 66 Despite the various terminology used, the appearance of such words in the confessions provided a chance for the CCP to investigate this issue further. However, the translators of the confessions were unlikely to be able to capture the subtle nuances of these Japanese words accurately, and translation into equivalent Chinese terms was nearly impossible. The phrase “comfort station” (ianjo) is a euphemism, literally denoting a place for comfort, and in most cases was transliterated as weiansuo 慰安所 in Chinese. The Japanese terms yūkaku, gikan and girō were translated as “brothel” (jiyuan 妓院 and jiguan 妓馆).Footnote 67 Intriguingly, shunya was rendered as both chunwu 春屋 (meaning brothel or place for prostitution) and weiansuo.Footnote 68 Language does matter because it shapes and structures judicial understandings of crimes to a certain degree. The Chinese transliteration of the Japanese euphemism ianjo obscured the criminal nature of the Japanese comfort station system; furthermore, the translation of the term as “brothel” rendered victims as prostitutes, thereby further stigmatizing them for having made money by sleeping with the enemy.Footnote 69 Moreover, as noted above, prostitutes were regarded as the direct victims of brothel keepers and indirect victims of old society, a scenario in which foreigners were not involved.

Third, the prosecutors may not have viewed Chinese comfort women as victims. Yun Xia points out that the dominant public discourse under the wartime KMT regime condemned not only females who were genuine collaborators and thwarted the resistance efforts through their activities but also those who were closely associated with Chinese collaborators and/or Japanese, regardless of their political stance.Footnote 70 She further contends that women who maintained sexual relationships with either Chinese male collaborators or Japanese occupiers were equally defiled and stigmatized.Footnote 71 Likewise, Akiyama Yōko has noted that female Chinese soldiers who were taken by the Japanese military as POWs were ostracized by their local communities after their release and labelled as “women who slept with the enemy.”Footnote 72 In the case of the comfort women system, the reasoning was that however reluctant Chinese comfort women may have been, by satisfying the sexual desires of the enemy, they had inadvertently helped to maintain Japanese men's morale, and thus they had contributed to the Japanese war effort.Footnote 73 Instead of being victims of sexual violence, Chinese comfort women may therefore have been viewed as collaborators by CCP prosecutors and the Chinese populace in general.Footnote 74 As Nicola Henry has pointed out, wartime comfort stations blur the responsibilities of the perpetrators by implicating female victims for their alleged complicity.Footnote 75 What Henry calls the “victim hierarchy” thus becomes conspicuous in the CCP's prosecution of sexual violence: victims of enforced prostitution were not classed as rape victims and appeared less authentic in terms of their victimization.Footnote 76

Whatever the reason for the decision not to prosecute the Japanese servicemen for these acts, this omission rendered invisible the suffering inflicted upon Chinese comfort women. Legal proceedings in the aftermath of mass violence serve to produce an authentic record of the crimes, to attribute responsibility and offer acknowledgement of suffering, and thus to contribute to the formation of collective memories.Footnote 77 Female victims in China were excluded from justice and their victimhood was not acknowledged in the CCP war crimes trials nor in society in general.

Conclusion

The above examination of the written confessions of Japanese war criminals and court proceedings illustrates that although sexual violence was detailed in the confessions, the CCP trials fell short of giving sufficient judicial attention to rape cases and failed to pursue the comfort women issue at all. This may be described as a historical example of selective justice, in which the CCP chose to focus on prosecuting only certain categories of war crimes. The CCP's legal treatment of sexual violence in the 1956 trials dovetails with the discourse on legal approaches to rape and prostitution expounded in the People's Daily. Legal cases involving rape were covered in the newspaper, but rape was mentioned only in passing and alongside other crimes. Prostitutes, with whom comfort women may have been associated, were regarded as victims in the public sphere. However, the dominant discourse manifested in the People's Daily attributed the suffering of these women to the old society and to procurers and pimps, rather than to clients. The CCP may have thus regarded prostitution as an issue already addressed in the domestic sphere, thereby finding it unnecessary to deal with it further during the war crimes trials of the Japanese detainees.

The CCP's treatment of sexual violence in the 1956 trials was compatible with its approach to gender issues in general. Gender equality was only one of many grand schemes promoted by the CCP, and women's issues were taken up only when doing so would be seen to benefit the larger socialist revolution.Footnote 78 By the same token, although rape was treated as a crime in the 1956 trials, it was not a major focus of the trials and was used only to prosecute other crimes. The CCP's legal approach to the issue of sexual violence therefore took place within the context of the discourse and propaganda reflected in the People's Daily and its attitude towards women's issues in general.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to Matthew Augustine and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful, constructive and critical comments. I would also like to extend my appreciation to the Fuji Xerox Kobayashi Fund, which funded my research for this article.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Bibliographical note

Xiaoyang HAO is a PhD candidate at Kyushu University. Her doctoral dissertation examines how a series of legal trials, including post-war war crimes tribunals and civil reparation trials, have treated the issue of wartime sexual violence.