Rapid urbanization in China has profoundly altered the landscape of its local governance, calling for a refocused inquiry into the impact of this transformation on the restructuring of power relationships between the socialist state and villagers in grassroots elections. In 1987, the promulgation of the Organic Law of Villagers’ Committees formally established the rights of villagers to elect their own leaders (cadres, or cun ganbu 村干部) and to participate in the making of decisions concerning village affairs.Footnote 1 Some research has found that grassroots elections have formally empowered villagers to vote out incompetent cadres who do not serve the interests of the village.Footnote 2 However, other works argue that village elections have remained state-manipulated owing to two main reasons. First, the socialist state has “no intention of relinquishing control” of rural society, despite a process of political decentralization that allows peasants to defend themselves, through elections, against abuses such as unscrupulous “gangster capitalism” by local cadres.Footnote 3 Second, village elections were not welcomed by local officials who worried that elected cadres might side with the voters to defy implementation of or compliance with unwelcome state policies.Footnote 4 Studies have found village elections to be fundamentally flawed processes, driven by rapacious and deceitful local officials seeking to maximize personal gain and sustain their positional power.Footnote 5 Consequently, the “feigned compliance” of local officials in promoting village electionsFootnote 6 and the ongoing attempts by the local state to manipulate election processes have constrained the effective participation of villagers striving for democracy.Footnote 7

The existing literature on grassroots elections in China seems to have overlooked how an authoritarian party-state has sought to transform itself at a time when rapid urbanization has heightened villagers’ awareness of social equities, economic interests and political rights. Over the past four decades, more than 500 million rural peasants have become urban residents in China. Land disputes and social conflicts have accompanied this massive wave of urbanization in many localities. To safeguard their interests, villagers have organized collective actions and resistance against rapacious land grabbing attempts orchestrated by corrupt, self-serving local officials.Footnote 8 Moreover, villagers have increasingly exercised their voting rights in formal elections to support village leaders who are prepared to repel top-down national policies that threaten to compromise their benefits and welfare.Footnote 9 As Huaiyin Li suggests, “for the younger generation of villagers growing up in the reform era, the traditional gap between the city and countryside was no longer unbridgeable; they strived to change their status from the stigmatized peasants to citizens who would be on equal footing with the rest of the nation and whose individual rights and choices would not be compromised.”Footnote 10

In the face of this shift towards villager “empowerment,” the socialist state cannot simply rely on coercive measures to maintain effective social control. Rather, as an emerging body of literature suggests, the socialist state and its local agents have adopted a flexible approach in managing social conflicts, with the aim of enhancing the state's political legitimacy. For example, to placate “land-losing” villagers and to address their economic and social demands, a district government in Guangzhou implemented a series of conciliatory measures that not only included progressive social welfare provision and shareholding reforms but also involved subtle interventions in village electoral politics.Footnote 11 In Beijing and Shenzhen, district governments have managed dissent through “protest bargaining, legal-bureaucratic absorption and patron-clientelism,” giving rise to a market-like exchange of compliance for benefits between the state and the community.Footnote 12 In defusing resistance, some municipal governments have agreed to conduct unorthodox institutional experiments, such as the promotion of land-based shareholding cooperatives in Nanhai 南海 and a land bill system in Chongqing.Footnote 13 Similar arguments can also be found about the adoption of informal institutions and the rural collective system by the socialist state as a pragmatic response to the social housing and welfare needs of villagers.Footnote 14 The socialist state has also recruited successful businessmen and entrepreneurial village leaders to be local Party secretaries and to act as role models of marketization with the aim of legitimizing the Party's leadership in grassroots governance.Footnote 15

All these changes of governing strategy point to the need for a refocused inquiry into the restructuring of the state–villager relationship in the context of grassroots elections. A fundamental question here is whether a transforming socialist state which has become receptive to open, competitive grassroots elections would engender and enrich the development of self-governance and grassroots democracy in urbanizing China. In addressing this question, we provide an empirical study of how the lowest rung in the socialist state (the township government or the district government and its street offices) has managed to transform its methods of intervention as villagers have become more active in grassroots elections. In China's administrative system, local state refers to all levels of government below the central government; in this study, local state refers to the lowest level in the state hierarchy, the level which has direct interaction with villagers and village cadres during grassroots elections and the daily administration of Chinese villages.

The State's Two-pronged Approach to Intervention in Elections

This study examines the lived experiences of residents in Y district in southern China. With a total population of approximately 370,000, Y district was traditionally a rural area where villagers relied on growing rice and vegetables to earn a living. Since the 1990s, owing to rapid urbanization, many villages in Y district have seen a significant growth in the value of their collective land and assets, giving rise to widespread tensions between villagers and village cadres over the management and distribution of collective incomes.Footnote 16 Against this background, the district government issued a policy document entitled, “Implementing elections for the Party branch/committee and residents’ committee in new urban neighbourhoods,” with a view to using grassroots elections as a means to address the conflicts between cadres and villagers.

Our field research focuses on ten villages, which were reorganized administratively into “urban neighbourhoods” (shequ 社区) between 2003 and 2005. Within these transitional neighbourhoods, which we term “urbanizing villages,” village traditions and norms continue to affect daily governance despite the fact that the villagers have had to go through a process of rural to urban transformation. Villagers have had their hukou 户口 converted from “agricultural” to “non-agricultural” status, and their villagers’ committees have accordingly been renamed residents’ committees (RCs). In these transitional neighbourhoods, urban institutions and practices have been gradually adopted, but informal institutions and traditions indigenous to the rural communities, such as the villagers’ sense of collective identity, their shared norms about kinship relations and their perceptions of authority and legitimacy, continue to influence daily interactions among villagers. This was vividly reflected during our interviews when local residents adamantly described themselves as “villagers” (cunmin 村民), even though they had become urban residents in an official sense. Moreover, villagers continue to collectively own some land for commercial uses.

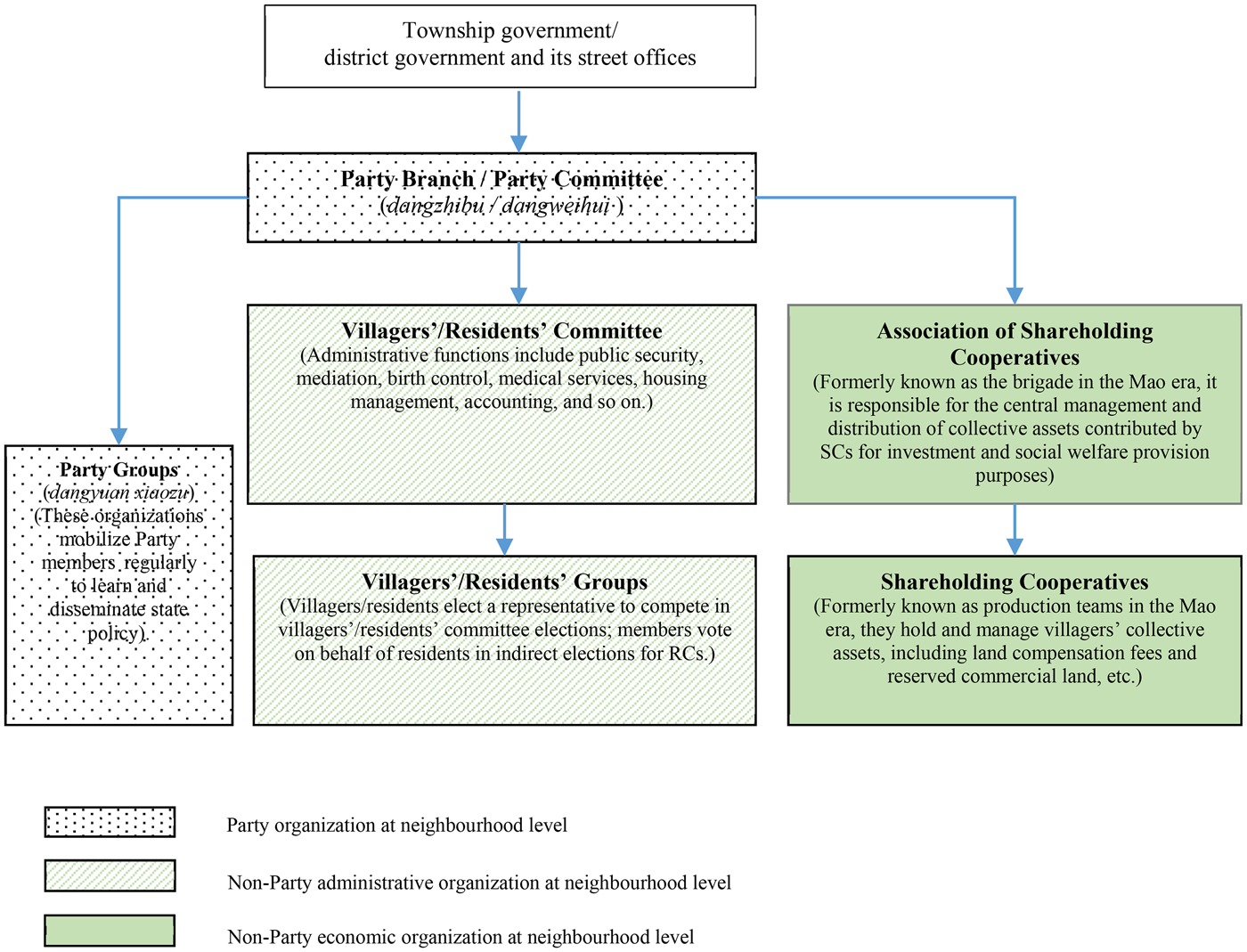

The transitional nature of these neighbourhoods is also reflected in their election arrangements, which still follow an organizational structure common to the Pearl River Delta called “two committees, one association” (liangwei yishe 两委一社).Footnote 17 The “two committees” are the Party branch/committee and the villagers’ committee (now RC) (see Figure 1). The Party branch/committee has the higher level of governing authority, while the RC oversees local administrative affairs including public security, mediation and birth control. “One association” refers to the association of shareholding cooperatives (ASC), which was formerly known as the brigade in the Mao era.Footnote 18 Under the ASC umbrella is a cluster of shareholding cooperatives (SCs), which were previously known as production teams.Footnote 19 Under the Maoist system, the management of collective assets was governed by three levels of authority: the commune, the brigade and the production team. In the 1980s, the commune in Y district was reorganized into a township government, although brigades and production teams continued to manage villagers’ collective assets. Under the shareholding reforms of the 1990s, the brigade and production teams were renamed the ASC and SC, respectively. These two levels of organization are also what villagers now call the village collectives (cunjiti 村集体).Footnote 20 Under the “two committees, one association” system, elections are held once every three years for each level – the Party branch/committee, the RC and the SC – to determine the administrative leadership and personnel in charge of these organizations.

Figure 1: Organizational Structure of “Two Committees, One Association” (liangwei yishe)

Between 2008 and 2018, we carried out intensive field research to investigate how these elections were conducted and the interactions between villagers and elected cadres in our case-study district. Through personal and professional connections with the local authority, we were granted on-site access to directly observe the behaviour of key local actors during the elections. Moreover, through conducting more than 150 structured interviews with local officials, cadres and villagers, we were able to evaluate the impact of the elections on a range of important local issues. Our findings suggest that the local state adopts two distinct strategies when managing Party and non-Party elections. On the one hand, it exercises tight supervision and close control of the entire election process for Party posts. On the other hand, it distances itself from elections for non-Party positions, including for the RC and SC, and actively encourages open and competitive elections. The remaining part of this article explores the reasons behind this two-pronged approach to local elections and its effects on grassroots governance. Grassroots governance here refers to how village affairs are governed, managed and administered. The study seeks to explore the interactions between local state actors (officials) and non-state actors (village cadres and villagers) in elections and the management of village assets and other activities. Local state actors here refers to the street offices, which are the administrative units of district government. It is the officials at these lowest echelons of the socialist state apparatus who are faced with the daily challenge of translating policy into practice and dealing with villagers’ demands for economic and social rights.

Villagers’ Participation in Grassroots Elections and Local Conflicts

In Y district, the villagers’ enthusiasm for elections began in the early 2000s and has grown steadily since. In the last four rounds of grassroots elections (in 2005, 2008, 2011 and 2014) for the SC and RC, all villages under this study achieved a voter turnout of more than 85 per cent. Two main factors have contributed to this. First is the payment of wugongfei 误工费, a form of compensation for labour lost, to villagers who vote in grassroots elections. Historically, it has been common practice for each villager to receive 50 yuan after casting his or her vote.Footnote 21 In the 2011 and 2014 elections, this payment was increased to 150 yuan. Second, and more importantly, villagers have become increasingly eager to vote as the wealth of the village has grown with the requisitions of collective land for industrial development. Similar to villages all across rural China, many villages in Y district began to hold elections in the early 1990s.Footnote 22 At that time, the villagers’ principal earnings came from farming and selling fruit to nearby cities.Footnote 23 As the performance of elected cadres had little impact on their personal incomes, villagers were not particularly interested in voting.Footnote 24

Since the late 1990s, however, massive-scale land requisitions by the local state have completely altered villagers’ attitudes towards elections. As land requisitions have left them more and more reliant on the village's collective income, villagers have grown increasingly keen to have a say in the management of the collective assets. Following the land requisitions, villagers received two types of compensation. The first was cash compensation. As all arable land was collectively owned, cash compensation was not paid directly to individual villagers. Affected farming households received cash compensation only for the agricultural products they had grown on the requisitioned land. The remaining and larger portion of the compensation money was held centrally by the village collectives.Footnote 25 The second category of compensation was in the form of “reserved commercial land” (ziliu jingji yongdi 自留经济用地). Villagers received about 10 per cent of the requisitioned land, which was “returned” by the government as part of the overall compensation. This reserved commercial land remains collectively owned and is managed by village collectives. It cannot be sold on the open market but may be legally leased to outside investors for non-farming use. The resulting rental income is then used to support villagers who have lost their agricultural land, and thus their livelihoods, to urbanization. For example, the collective for one Y district village which had lost all of its arable land to urbanization by 2002, held nearly 100 million yuan in compensation.Footnote 26 Another village collective generated a total rental income of 3.3 million yuan a year by leasing 1,100 mu of “reserved commercial land” to investors for factory and office uses.Footnote 27 The income generated is usually split between funding village infrastructure projects and social welfare provision, and the payment of dividends to individual villagers.

Some scholars have suggested that residents in wealthier villages tend to be less politically engaged with village elections primarily because they derive their household incomes from economic opportunities outside the village.Footnote 28 In Y district, however, strong voter participation in grassroots elections is directly related to the growing economic wealth of the villages. After losing their land to urbanization, the villagers in Y district found it difficult to get non-farming employment and they had to rely on income from the collective assets. This meant that the villagers no longer had sole control over their economic well-being, as their assets were now in the form of cash (land compensation fees and rental income) and this huge sum of money was in the hands of cadres who decided what it was to be used for and how it was to be paid out. Many villagers started to worry that they might lose all of what they had owned if corrupt cadres, for example, were to run away with their money. Given these considerations, they chose to actively participate in elections in an attempt to hold cadres accountable for the management of collective assets.

The competitive elections for the decision-making positions within the village collectives have rekindled the influence of kinship and lineage networks in the daily governance of villages. Throughout generations, lineage networks have long played an important role in many aspects of Chinese village life.Footnote 29 The origin of the villages in Y district can be traced back to the Song dynasty (960–1279), when the Zhong family was the first to move there and build a settlement. Gradually, more families with different surnames, such as Liu, Kong, Huang, He, Luo and so forth, arrived to build their settlements, the so-called “natural villages.” To illustrate with an example, one village in this study contained nine natural villages, in which three big families, Zhong, Liu and Lai, along with some minority families with the surnames Chan and Xiao, had lived together for centuries. During the Mao era, these natural villages were divided up into 13 production teams under the supervision of a brigade. The enduring efforts of the Chinese Communist Party to transform the countryside substantially undermined these traditional lineage networks.Footnote 30 Such effects served to weaken but not dismantle the traditional social organization of the villages.Footnote 31 After the implementation of the household responsibility system in the early 1980s, the Chinese government shifted its policy focus to the development of cities. Consequently, the retreat of the state from villages allowed a revival of informal village norms, culture and customs, which continue to influence daily governance practices.Footnote 32

Since the early 1990s, traditional clan-based power blocs have re-emerged in Y district because of two main reasons. First, the implementation of the “reserved commercial land” policy, coupled with an urban-biased development strategy, has consistently undermined the presence of the state in rural areas. Throughout the 1990s, the township government devoted all its energy to strategic industrial development, leaving villagers to rely on their own village collectives for both social welfare provision and personal income. This provided an opportunity for resurrected clans to take over village administration and grow their villages into wealthy and autonomous entities.Footnote 33 Second, the promotion of self-governance and democratic elections has enabled powerful village families and clans to extend their influence over local decision making through village elections and the management of the villagers’ committees. At election time, unsurprisingly, the voting behaviour of villagers is influenced by informal institutions such as kinship ties, family power relationships, and so forth. While villagers in general first pay attention to a candidate's credibility, leadership and administrative capabilities, particularly his/her integrity and past performance in the management of collective assets, blood ties and family lines still play a significant role when villagers come to decide for whom they will vote. In general, many villagers still favour a candidate from their own lineage to represent them in the management of the community.Footnote 34

A village cadre indicated that he had devoted all his energy to winning the election because his defeat would shame not only himself but also his entire lineage.Footnote 35 Candidates not only appeal to voters on the basis of their personal attributes or administrative calibre but also on the basis of blood ties and family connections, capitalizing on voters’ preference to see one of their own in a leadership position within the community. Such lineage-based loyalty is not without problems, however, especially for those elected on this basis. In order to secure the support of their clan members, cadres are expected to consistently favour their own clans in local administrative matters. One cadre indicated that he felt extremely frustrated, as his relatives treated him as an enemy after he had become involved in demolishing their “illegal houses.”Footnote 36 To demonstrate his impartiality, he chose to start enforcement actions against the buildings owned by his sister and other close relatives. However, most members in his clan condemned him and refused to maintain contact with his family afterwards. Losing the support of his clan, he was worried that he would be voted out in the next round of elections.

Politically unified clans and large families are more likely to gain control over the management of the village's collective assets and affairs. In Y district, members of the Zhong and Liu clans have occupied the key posts in the villagers’ committee for over ten years. These elected cadres tended to implement measures that favoured their kinsmen, at the expense of the villagers from other, smaller clans. From the perspective of local officials, village elections can lead to a “tyranny of the majority,” which can be a source of social instability in villages.Footnote 37

State Intervention in Grassroots Elections

Villagers versus cadres: a potential crisis in grassroots governance

The existing literature emphasizes the role land disputes between the local state and the villages have played in shaping the complexity of local governance restructuring.Footnote 38 In the case of Y district, however, the potential conflicts between the indigenous cadres and the villagers were decisive. Implementation of the “reserved commercial land” policy, as part of the compensation to villagers during the state-led urbanization process, contributed to a rapid growth in the value of the property assets of the village collectives during the 1990s.Footnote 39 As mentioned above, following land requisitions, cadres were responsible for managing all collective assets, including the land compensation fees and the rental income derived from “reserved commercial land.” The revival of clan-based power blocs and the ambiguity of collective ownership created many grey areas which cadres could manipulate when managing village assets and wealth to the detriment of non-clan villagers. This situation was exacerbated as the rise in the value of the collective property assets generated greater incentives for cadres and Party members to engage in cheating, fraud and illegal undertakings.

Throughout the early 2000s, as more and more arable land was requisitioned, many internal conflicts over the management of the collective assets and the distribution of incomes were brought to the surface, leading to direct clashes between cadres and villagers. During our field research, we heard stories about cadres receiving kickbacks from contractors involved in village construction projects.Footnote 40 Even worse, some village cadres had used the collective funds for their own personal enjoyment and one had even gambled away all of the land compensation fees. In response to one such incident, some villagers vented their anger by burning down the villagers’ committee office. In order to resolve this particular dispute, the district government had to quickly inject money back into the village's collective account as well as penalize the cadres who had misappropriated the village assets.Footnote 41 On top of hostilities against cadres, villagers also raised their complaints with the local government offices, either through open protests or by submitting petition letters.

The villagers were not opposing the local state or government officials in any of these episodes of grassroots struggles. According to the villagers who participated in the petitions and protests, they only wished to reprimand the cadres who unfairly and consistently distributed collective incomes in favour of their own clan members.Footnote 42 Some villagers demanded that the local officials from the street office attend their meetings as adjudicators and to listen to their grievances and hear reports of cadre malpractice. Villagers’ welfare benefits such as medical services and pension schemes are all funded by the compensation fees and property assets held by the village collectives. The district government quickly recognized that any breakdown in this funding model caused by corrupt cadres would escalate into widespread social instability in the villages and inevitably undermine the political legitimacy of the Party. Therefore, a popular vote by the villagers to elect cadres to manage their village assets was not sufficient to ensure good village governance.

In an attempt to enhance the quality of village administration, the street offices experimented with appointing outsiders to govern these urbanizing villages. In the early 2000s, the district government launched an “undergraduate trainee programme” (peiyang daxuesheng cunguan jihua 培养大学生村官计划), through which it recruited fresh graduates to work in the RCs.Footnote 43 The primary purpose of this programme was to nurture young talent to be the new leaders and encourage them to participate in grassroots elections in order to neutralize the political influence of traditional village power networks. However, the programme failed in its objectives, as only one trainee was eventually elected to the RC.Footnote 44 The district government learnt from this failure that indigenous leaders were indispensable players in village administration.Footnote 45 It therefore became a political necessity for the local state to rebuild the villagers’ trust and confidence in their indigenous leaders. In order to achieve this, it was crucial to identify capable and respectable cadres from the villages. The district government put into practice two separate but interrelated governing strategies, one to manage the Party elections and the other to manage the non-Party elections. Put simply, the aim was to keep a firm control over the elections for Party branch/committee positions, but deliberately give free rein to elections for other non-Party grassroots organizations such as villagers’ committees (now RCs), villagers’ groups (now residents’ groups) and SCs.

Authoritarian Party electionsFootnote 46

In each round of grassroots elections, Party branch/committee elections are conducted prior to the elections for the RC and SC. Village cadres in these urbanizing villages described the process to elect members to the Party branch/committee as “two nominations and one election” (liangtui yisuan 两推一选). “Two nominations” means that candidates are nominated in two ways: internal nomination by Party members (dangnei tuijian 党内推荐) and external nomination by villagers’ representatives (qunzhong tuijian 群众推荐). The number of candidates typically exceeds the number of elected positions by 20 per cent. The Party branch first convenes a meeting of all Party members in the neighbourhood/villages to nominate candidates. Each nomination is valid only if it has the support of two-thirds of the members. Simultaneously, candidates are also put forward by a committee formed of non-Party members that includes villagers’ representatives, heads of residents’ groups and former members of the RC.

The list of nominees has to meet the approval of the street office. A primary concern for the street office is to make sure that the candidates have faithfully followed and implemented state policies and duties. This usually eliminates candidates who are known to have taken part in protests against the state or who have violated specific national policies such as birth control regulations. Party groups organize regular classes for their members to study Party policy, and require them to submit annual self-appraisals to the Party committee. This allows the street office level to have continuous assessments of its members at the village level.Footnote 47 The street office also welcomes candidates who are popular among the villagers. This generally rules out candidates with a record of wrongdoing in the management of collective assets and/or who have had open disputes with other clans in the village. After finalizing the list of candidates, the Party branch calls a general meeting to elect the secretary and the members of the Party branch/committee: the so-called “one election” after “two nominations.” The voting is done via a secret ballot during the meeting. The relevant policy document states that at least 80 per cent of the locally registered Party members must attend the meeting in order for the ballot to be valid. However, it does not specify the rules for determining the winning candidates, even though candidates with the highest number of votes are mostly declared elected. This leaves some room for the street office to have a final say when the results of the elections are submitted for its endorsement.

These procedures mean that not only are street offices empowered to influence the nomination of candidates but they also have much discretion over which nominees actually appear on the winning list. There are obvious reasons why the district government directed its street offices to concentrate attention on the Party branch/committee elections. As shown in Figure 1, the Party branch/committee is the highest level of authority in village administration. As the head of local authority at the grassroots level, the secretary of the Party branch/committee also assumes the directorship of the ASC. Therefore, in addition to handling community affairs, this person is also in charge of managing all collective assets held under the ambit of the SCs.

This arrangement means that the leadership of the political and economic management of the villages falls under the direct guidance of the Party branch/committee. Furthermore, the Party branch/committee actively encourages new, capable villagers from within the neighbourhoods to become Party members and then nurtures them to become village leaders. By keeping control of the Party branch/committee elections, the state is able to cement its political interests and maintain an influence over the local administration and management of collective assets. In contrast to its deliberate attempts to manipulate Party elections and expand the Party organization at the neighbourhood level, the district government takes a very different approach to the RC and SC elections.

Open and competitive non-Party electionsFootnote 48

We found that the district government did not attempt to interfere with the nomination of candidates for the RC and SC elections. Although the Party secretary usually serves as one of the members of the electoral affairs commission, he/she cannot determine or dictate who is on the list of nominations directly, because the avenues for candidate nominations are open and the opinions of the other villagers’ representatives in the commission cannot be ignored. In fact, all eligible villagers are free to nominate and vote for their own candidates. In the final election, voters can write down their choice of candidate directly on the ballot paper if they disagree with the candidates already nominated on the list.

In 2005, villagers in Y district began to elect RC directors and committee members to fill positions concerned with accounting, public security, birth control, conflict mediation and conscriptions. Reorganizing villagers’ committees into RCs did not bring about any fundamental changes to the election procedures for these committees, but it did allow the villagers more flexibility in choosing their method of election. According to the Organic Law on the Organization of RCs, committee members can be elected by a direct ballot of all residents (direct election), or elected by the villagers’ representatives (indirect election). In the case of direct election, the quorum is set at 50 per cent and a candidate has to secure a majority vote in order to win the seat. In the case of indirect election, the quorum is set at a higher level: at least two-thirds of the representatives are required to attend the election meeting and the winning candidate has to win more than half of the votes.

The election method is decided by the electoral affairs commission, which comprises the Party secretary, the existing committee members and the elected villagers’ representatives. If the electoral affairs commission decides to go down the route of direct elections to choose RC members, all registered villagers aged 18 or above are eligible to vote for their preferred candidate. If the commission opts for indirect elections, committee members are elected by the voters’ representatives, who have been elected at the residents’ group level. In recent years, while many villages in Y district still continued with direct elections, some had switched to indirect elections by residents’ representatives. Village cadres and villagers suggested that two considerations had influenced their choice of electoral method.

First, indirect elections involve less complex procedures and thus incur lower administration costs. As a major part of the expenditures for elections are funded by the village collectives, villagers generally tended to support the cheaper election method.Footnote 49 Second, the election method also affects the decision-making process in day-to-day community management. This is because the same election rules are used when determining the collection of fees, the allocation of collective income, the construction of roads or other public projects, and the provision of welfare programmes in the villages.Footnote 50 Therefore, indirect elections were generally favoured by the villagers, because direct elections were considered to be too cumbersome and time-consuming for day-to-day decision-making.

However, there is a major shortcoming with indirect elections in that they make it easier for some powerful clans to dominate the political scene. Under indirect elections, every 20 to 30 households elect one villager to represent them on the residents’ group. These representatives then vote in the election of the RC on behalf of their voters. The total number of households in each village usually ranges from 400 to 800. If indirect elections are adopted, only about 20–50 representatives would be selected to vote in the final election of RC members. In this case, some candidates could easily lobby the villagers’ representatives and influence their decisions during the run up to the election. But, in the case of direct elections, it is considerably more difficult for candidates to influence the outcome, as they could not possibly sway the hundreds of villagers entitled to vote. Given the pros and cons of these two methods, those villages in Y district in which cadres and villagers had established a high degree of mutual trust tended to follow the indirect election route.Footnote 51 In contrast, the villages where tensions between cadres and villagers had long existed continued to opt for direct elections when selecting members of the RC.Footnote 52 For instance, one village we visited had initially opted for indirect elections. However, when it came to light that cadres had been using the collective income for their own private use, the villagers not only burned down the cadres' offices but also reverted back to the “one man, one vote” direct election system.Footnote 53

Both direct and indirect elections are subject to standardized government procedures. They generally involve five major steps. The first is to form an electoral affairs commission, which then proceeds to draw up a register of all qualified voters. The list of registered voters has to be made available for the villagers’ inspection for at least 20 days prior to the formal election. The third step is the nomination by villagers of candidates for election. Under a multi-candidate electoral system, two candidates are usually nominated to compete for the position of director or deputy director. For the election of committee members, usually two or three candidates compete for each position. The fourth step involves the selection of three to seven villagers’ representatives to act as election observers. They are responsible for monitoring the entire voting process and scrutinizing ballot-counting operations. The final step is the actual casting of ballots by all qualified voters. All ballots have to be counted and the results of the elections declared on the same day.

Similarly, elections for SCs are held once every three years. They come after the elections for Party branch/committees and RCs. The SCs are the officially recognized self-governing bodies responsible for the management and distribution of collective assets. The SC elections follow the principle of “one man, one vote.” During the 1990s, the number of shares held by each villager in Y district varied from time to time, because the shareholding rights of all eligible individuals were re-allocated every three years to accommodate for the changes in age and size of the village population.Footnote 54 Each shareholder still held an equal vote despite holding different amounts of shares. In the early 2000s, the district government introduced a new policy termed the “consolidation of share right” (guhua guquan 固化股权), under which each villager was allocated an equal number of 200 shares and reallocation would no longer be permitted. The principle of “one man, one vote” was still maintained.Footnote 55

In each round of elections, villagers select candidates to fill the posts of director (shezhang 社长), deputy director (fushezhang 副社长) and accounting manager (chuna 出纳) in their respective SCs. These elected cadres are entrusted with two important tasks. First, they look after the daily management of villagers’ collectively owned assets. Another task is to represent their fellow villagers on the board of directors and the board of supervisors of the ASC, which makes decisions on the allocation of collective assets for the development of village facilities and social services. The number of directors (the elected leaders from the different SCs) varies from three to nine, depending on the size of the village population. Further, a board of supervisors, comprising three to four elected leaders from the villagers’ representatives, is formed to oversee the performance of the directors and monitor the financial affairs of the SC.Footnote 56 Compared with the villagers’ committee elections, more freedom and flexibility are permitted in the SC elections. Villagers are allowed to write the names of their preferred candidates for the three aforementioned posts on the ballot papers. After the election, the performance of these “write-ins” is closely monitored and supervised by their fellow villagers, who can then vote them out in the next election if they do not act in the interests of shareholders. The role of the local state in non-Party elections is to ensure that the election results are not manipulated and that the electoral procedures are strictly followed according to official guidelines. During the RC and SC elections, as some local government officials from the street office suggested, villagers are encouraged to wait at the polling station to hear the announcement of election results. Cadres thus take great pains to conform with every step in the election process in order to survive the scrutiny of the village electorate and the supervision of local government officials.

Grassroots Governance Capacity Building and State Penetration

A direct consequence of this two-pronged approach of state intervention into elections has been the rebuilding of the political legitimacy of RCs and SCs, which had been undermined by the persistent confrontations between indigenous leaders and villagers in village management. The street office desires the elected Party secretary and Party committee members to be not only loyal to the party-state but also popular among villagers. The nomination process in Party elections removes candidates who are known to be corrupt or incapable of balancing the interests of their own clan families with the interests of others. To enhance their accountability, the elected Party secretary and Party committee members are required to take part in the open elections for the RC and SCs. Most win positions in these two elections. Consequently, in most of the villages under this study, the Party secretary also assumed the position of RC director and Party committee members also served as director or deputy director of the SCs. The legitimacy of the elected leaders is effectively enhanced through these open and competitive non-Party elections, despite the fact that they are “hand-picked” nominees in Party elections.

From the perspective of the villagers, the elected cadres now had greater representativeness. Some villagers suggested that because the nomination and election procedures were very clear to them, the elections seemed more “democratic.”Footnote 57 Formal and rigorously designed electoral procedures are essential to increase villagers’ confidence in the elections and their trust in the elected leaders.Footnote 58 This was certainly the case in the villages under this study. Some villagers suggested they were more willing to accept the election results even though the candidates they supported did not win in the final election. Moreover, villagers considered that many of the elected cadres were more “dedicated” to fighting for their interests and to improving the welfare facilities of villagers. As evidence of this, they pointed out to us that the elected members of an existing RC had just renovated a building to house a neighbourhood clinic so that villagers now had access to better and more convenient medical services.Footnote 59

Some scholars have described the elected cadres as “Janus-faced intermediaries” who represented the party-state policies to the peasants and the peasants to the party-state.Footnote 60 Our field research shows that the cadres have become more willing to act as agents of the state and implement state policy for two main reasons. First, street offices are able to eliminate corrupt and incompetent Party secretaries by removing them from the Party organization. Second, cadres still have to rely on the support of the district government to reinforce what Dingxin Zhao calls “performance legitimacy” in the daily governance of the urbanizing villages after the elections.Footnote 61 For the villagers in Y district, democracy was a high-sounding principle, and it had to be backed up by material results. Whether something is democratic or not does not solely depend on the fairness of the electoral process and procedures; it is also judged by the outcomes of community management.Footnote 62 Villagers were most concerned about their social welfare provision and dividend payments. Yet, in order to generate stable collective incomes that could go towards improving village welfare and dividends, the elected cadres had little choice but to obey the district government, which held the decisive authority over land-use planning and the development of village property assets.

The local state could adjust its policy on village land development matters, and in so doing, affect the performance of cadres in the eyes of villagers. For instance, following a request by some cadres in one village, the local government agreed to sign a long lease on rented premises built on the village's “reserved commercial land,” thereby guaranteeing that the villagers received an annual collective income of nearly 40 million yuan.Footnote 63 Securing this contract meant that the cadres could demonstrate to the electorate that they were following through on their promise to fight for the best interests of their fellow villagers. The blessing of the local state was highly instrumental to the success of these elected cadres; if it had not lent its support to the proposals, the cadres could have “lost face” in the eyes of the villagers, who then might have voted for other candidates deemed more capable of securing a better deal in land leasing to the government.Footnote 64

In exchange for material concessions from the local state, elected cadres have to toe the line by implementing its policies and fulfilling duties in a range of areas including, but not limited to, building control, social security, conscriptions and village redevelopment. Since 2009, the municipal government of Y district has progressively promoted village redevelopment. One of the key tasks handed to the cadres by the district government was to combat and soften the resistance of some villagers who disagreed with redevelopment. To appease villagers, the district government used its discretionary power to relax some of the redevelopment restrictions, so that cadres could have more room for negotiation with the villagers over their requests for higher compensation.Footnote 65 In the process, the cadres turned the controversy about village redevelopment into a manageable task by focusing on practical issues that they could discuss with the local state on behalf of their fellow villagers. These issues included not only the amount of compensation but also the location of a new subway exit to improve village accessibility and therefore increase the value of the villagers’ own properties.Footnote 66 When the district government was able to be flexible in its response to villagers’ negative reactions to village development proposals, not surprisingly the cadres were more inclined to stand behind the state, even though the cadres repeatedly emphasized their role as an intermediary between the state and villagers.Footnote 67

Conclusions

Open and competitive elections of village cadres have provided formal channels through which villagers can defend their entitlement to the expanding collective assets and wealth generated by urbanization. To secure villagers’ support in elections, cadres need to honour the expressed demands of villagers for the fair distribution of collective income and adequate provision of welfare benefits in their villages. Our study, however, indicates that the current trend of villager empowerment in grassroots elections is still a far cry from being a driver of bottom-up political changes in urbanizing China. Drawing from the lived experiences of residents in Y district, we highlight two key observations about the effects of grassroots elections on reshaping state–villager relationships.

First, the villagers in Y district wished to use elections to regulate the behaviour of their cadres rather than the socialist state per se. With their primary concern focused on safeguarding the growth and distribution of their village wealth, the villagers were most interested in what material benefits they could gain through grassroots elections. Motivated by pragmatic considerations, they were not so eager to use elections as a political means to alter the prevailing political norms and structure when they were satisfied with and pacified by discernible improvements in their collective income, community facilities and welfare benefits. Thus, it is difficult to see how the active participation of villagers in elections will eventually evolve into a critical mass of autonomous forces with the potential to challenge the political regime of the socialist party-state.

Second, the local state's support to promote open and competitive elections was dominated by a utilitarian concern about how to eradicate social instability through the better supervision of village affairs and prudent management of collective assets. The effective political control of the state was not achieved through the direct appointment of local officials to grassroots administrative positions, nor by giving villagers a free hand to select their leaders through elections. Using a two-pronged approach, the local state first sought to tighten its control over Party elections by determining the candidature of the village leadership; and second, it progressively promoted competitive elections for non-Party positions in village collectives. Behind this strategy, the local state nurtured competent indigenous candidates to occupy key positions in villagers’ economic and administrative organizations by supporting them to gain popularity and build a rapport with the villagers through open and competitive elections. It also stepped up its timely intervention in potential confrontations between villagers and elected cadres to prevent them escalating into widespread instability at the grassroots level.

To conclude, the recent trend in the development of grassroots elections has involved both authoritarian state domination and democratic bottom-up participation. It has directed local governance in urbanizing China to what John Friedmann describes as a path of transformation, “between two poles of ever-present danger: the lapse into anarchy and the reimposition of a totalitarian rule leading to stasis.”Footnote 68 Alongside this transformation, there are encouraging outcomes of self-governance where grassroots elections have succeeded in warding off political instabilities caused by corrupt and incompetent village cadres. This, however, should not lead one to overlook the fact that villagers have had to increasingly rely on the local state to rein in the misconduct of cadres, adjudicate on inter-clan disputes, supply talented Party cadres to take up leadership positions, and provide economic opportunities to expand collective incomes. In other words, the local state holds the reins not only on the candidature of elections but also on the possible achievements of these elected cadres for the village collectives after elections. The current electoral arrangement actually constitutes a subtle form of political intrusion by the socialist party-state into village affairs, which may in turn impede the development of self-governance by villagers.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions on the earlier versions of this manuscript. We are particularly grateful to the late Professor John Friedmann, who gave tremendously valuable feedback on the first draft of this manuscript. The usual disclaimers apply. We are also indebted to all the interviewees who generously shared their stories and information with us in this study. The work described in this paper was supported by a research grant (Project No. PolyU 25203215) from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China, and an international grant (Grant No. 0175-1049) from the Ford Foundation.

Biographical notes

Siu Wai WONG is assistant professor in the department of building and real estate at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. She received her PhD in planning from the University of British Columbia, Canada. Her research interests are related to urbanization in China, urban planning and governance.

Bo-sin TANG is currently professor in the department of urban planning and design at the University of Hong Kong. He was previously professor and associate head of the department of building and real estate at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. His research interests cover urban planning, land development and institutional analysis.

Jinlong LIU is professor in the School of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development at Renmin University of China. His research interests cover forestry development, public participation and community development. He provides policy advice to the Chinese government, World Bank, Asia Development Bank, FAO and UNDP, among others, in the areas of sustainable forestry management, community engagement, sustainable rural development and poverty alleviation.