In his work The History of Sexuality, Foucault argues that state control of the individual's body and sexuality in the name of public health can be a source of repression.Footnote 1 Historians have produced an impressive account of the historicity of state discourses and disciplinary practices related to prostitution.Footnote 2 These scholars concur that the issue of prostitution control cannot be separated from the rise of public health discourse as a technology of power.Footnote 3

The latest figures released by the UNAIDS report estimated that there were 700,000 people living with HIV in China in 2007, including about 75,000 AIDS patients.Footnote 4 Among the newly reported cases in 2007, the government claimed that 37.9 per cent were infected through heterosexual transmission and singled out sex workers and their clients as high risk groups, among others.Footnote 5 UNAIDS estimated that there were 127,000 female sex workers and their clients living with HIV in China in 2005.Footnote 6 These figures are alarming, but at the same time need to be interpreted with caution because of what Mary-Jo Good termed the “aesthetics of statistics.”Footnote 7 In her book on the cultural politics of AIDS, Sandra Hyde convincingly showed how political, social and cultural prejudices have influenced the surveillance, screening and testing of HIV among the so-called risk groups, and hence the production and use of HIV/AIDS statistics.Footnote 8 While we have to rely on government statistics to grapple with the magnitude of the vulnerability of sex workers to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, we are constantly aware that these figures have been produced within existing social contexts which frequently mark sex workers as contaminated and needing to be rescued, disciplined and controlled. The AIDS crisis has further accentuated the disciplinary discourse. This article argues that it has prompted a gradual shift in the state narrative of sex workers as victims of social systems to victimizers who spread diseases. The victimizer discourse in turn has justified the introduction of harsher measures against prostitution since the late 1980s as a means of disease control.Footnote 9

State Discourse and Action before AIDS

After the Communist Party came to power in 1949, it made concerted efforts to eradicate prostitution. However, although its rhetoric in doing so was harsh, its measures were not intended as punishment. The closure of brothels and the detention of prostitutes was for rehabilitation rather than punishment.Footnote 10 While pimps, panderers and those who forced women into prostitution were treated as criminals and faced severe punishments, including the death penalty, prostitutes were viewed primarily as victims. In the words of the Party, they were “the most exploited women,” “fallen wanderers,” and the spirit of government action was not to punish them but to “restore to normal their distorted souls, eliminate their bad habits.”Footnote 11 The tone of state discourse at that time was one of sympathy rather than condemnation, and coercive measures were mainly seen as a necessary evil because the souls of prostitutes were supposedly contaminated by the trade.Footnote 12 Consequently, facilities where women were detained were named “shelters” (shourongsuo 收容所). State propaganda highlighted the role of these reform facilities in re-educating, training and nurturing (jiaoyang 教養) women to be self-sufficient new citizens (xinsheng renmin 新生人民).Footnote 13 Responsibility for handling prostitutes was not placed with the judicial system, but upon designated personnel within the Public Security Bureau, the People's Procuratorates and area members of the Women's Federation. The ultimate goal was to instil the moral standards of the new socialist state upon these women and to reintegrate them into family and work networks.Footnote 14 In legal provisions, such as the 1957 Act of the People's Republic of China for Security Administration Punishment, selling of sex carried a misconduct connotation. Under the provisions of the Act, a woman caught prostituting could be given a warning, or placed in detention for a maximum of ten days and fined up to 20 yuan.Footnote 15

The state's rhetoric about prostitutes as victims and its legal treatment of prostitution as a minor offence rather than a crime continued right up to the promulgation of the country's first modern legal codification, the 1979 Criminal Law of the People's Republic of China.Footnote 16 Because of the conception of prostitutes as victims, the law unleashed severe punishments on their supposed victimizers – the traffickers, pimps and brothel owners. Under this law, forcing a woman into prostitution carried a minimum sentence of three years’ imprisonment and a maximum of ten (article 140). Enticing a woman to exchange sex for money, or providing her with accommodation in which to do this, could carry a sentence of five years or more, in addition to a fine or confiscation of property (article 169). Human trafficking carried a five-year sentence.Footnote 17 On the other hand, the legal treatment of prostitutes remained a duty of the Security Administration Punishment Act under the Public Security Bureau.Footnote 18

In 1981, the Public Security Bureau issued a document to “sternly stop prostitution.”Footnote 19 Although this document criticized prostitution for damaging the moral culture of society (pohuai shehui daode fengshang 敗壞社會道德風尚) and for constituting a threat to social order and stability (weihai shehui zhixu de an'ding 危害社會秩序的安定), the tone remained one of acknowledging that those who forced women into prostitution were the criminals (fanzui fenzi 犯罪份子) who needed to be punished, while prostitutes continued to be regarded as victims who needed to be educated and rescued (jiaoyu wanjiu 教育挽救). The document also continued to place emphasis on women's ignorance as the main reason for their involvement in prostitution. It stressed the need to “patiently educate” (naixin jiaoyu 耐心教育) “fallen young females” (shizu nüqingnian 失足女青年). It also cautioned against discrimination (qishi 歧視) and intrusion into the work, study and life of those who had repented (gaizheng 改正).Footnote 20

State Discourse and Action after AIDS

Concomitant with the AIDS crisis, there has been a visible change in state discourse. In 1986, the State Council issued an announcement which asserted that its purpose was “to sternly uproot prostitution and stop the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STI).”Footnote 21 In this document, prostitution was portrayed as the main culprit for the spread of STI and subjected to increasingly severe legal treatment. Prostitutes and clients who were first-time offenders continued to be dealt with under the Security Administration Punishment Act, but this now contained an additional provision requiring the authorities to inform both the families of the offenders and local security bureaus.

For prostitutes and clients who were re-offenders, severe penalties were introduced (congzhong chufa 從重處罰). It is notable that the word “punishment” rather than the usual terms of “education” or “rescue” were used in respect of re-offenders. In a subsequent report entitled “Report about cracking down and uprooting prostitution and stopping the spread of STI,” this shift in state discourse to define prostitutes as criminals rather than victims was even more pronounced. Prostitutes and their clients were grouped together with other people involved in prostitution (pimps, panderers and traffickers) and categorized under the same term “illegal criminals” (weifa fanzui fenzi 違法犯罪份子). The report clearly implied that prostitutes were responsible for spreading venereal diseases by asserting that “following the increase of selling and purchasing of sex, STI also spread.” It further claimed that prostitutes participated in criminal activities by stating that “women who sell sex often gang together in groups of three, five, or even more than ten people according to their native origins. They are active in hotels and restaurants, and form a chain with other criminal activities” (xingcheng liansuo fanying 形成連鎖反應). It also distinguished prostitutes in old China from their contemporary counterparts by claiming that “the women who sell sex in contemporary times are completely different from those in old China who were mostly forced into prostitution for survival (poyu shengji er maiyin 迫於生計而賣淫). The prostitutes now mostly indulge in material comfort (tantu wuzhi xiangshou 貪圖物質享受), are lazy (haoyiwulao 好逸惡劳), and pursue the life style of parasites (zhuiqiu fuxiu de jisheng shenghuo 追求腐朽的寄生生活).”Footnote 22 By implicating them in criminal activity, by attributing their engagement in prostitution primarily to their moral deficiency and by alleging their role in the spread of STI, prostitutes were reflected in state discourses as victimizers who needed to be held accountable for their actions.

The boundaries between crime and non-crime with regard to prostitution have become even more indistinguishable since then. National and local official documents issued after 1987 have begun to group selling and purchasing sex with selling and using drugs, human trafficking, organized crime and gambling into “criminal activities” (weifa fanzui xingwei 違法犯罪行為).Footnote 23

The discourse of prostitutes as victims did linger to some extent, as shown by the focus on abductions of women and children during 1990 and 1991, the formulation of prostitutes as victims of traffickers and pimps by some segments of the government, and the enactment of the 1992 Law Protecting Women's Rights and Interests.Footnote 24 Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the victim discourse was gradually eclipsed by the victimizer discourse that found expression in an amendment to the Criminal Law in 1997. This amendment signalled an important turning point in the legal status of prostitution: a new clause stipulates that those who knowingly sell or buy sex while infected with syphilis, gonorrhoea or a sexually transmitted infection will be prosecuted and punished with jail sentences, criminal detention or public surveillance for a maximum of five years. Needless to say, this new provision targets and affects sex workers.Footnote 25

Another major means used by the state to combat prostitution is campaign-style policing (yanda yundong 嚴打運動). This is the use of concentrated efforts to target special categories of illegal activities within a fixed time for arrest and severe punishment. The most prominent nationwide campaigns targeting prostitution were organized between 1983 and 1987, and between 1990 and 1996.Footnote 26 They are characterized by large waves of arrests, swift trials without due process, heavy official publicity, public parading, mass sentencing rallies and public displays of crime scenes.Footnote 27 Arrest figures reflect the intensified control of prostitution since the onset of the AIDS crisis in the late 1980s. In 1982 a total of 11,500 arrests related to prostitution were made. In the first six months of 2000 the number was 297,361.Footnote 28

The wordings used in the high-profile campaigns provide further evidence of the shift in state discourse about prostitution. When the first campaign was launched in 1983, it meted out severe punishment, including the death penalty, against those who “lure, house and force women into selling sex,” but did not specifically target the selling and purchasing of sex.Footnote 29 The relatively lenient treatment of prostitutes and their clients reflected the pre-reform and early reform period conceptualization of prostitutes primarily as victims of sexual exploitation. However, in the second nationwide campaign launched in 1990, severe punishments were also imposed on “unrepentant (lüquan bugai 屢勸不改) prostitutes and their clients.”Footnote 30 This shows an end to the pre-AIDS crisis attitudes, where legislation and provisions treated these two groups of people as qualitatively distinctive categories, with pimps and traffickers treated as criminals, and prostitutes and their clients as minor offenders.

By demonstrating how the AIDS crisis has prompted the post-socialist Chinese state to shift its discourse and intensify its control over prostitution, this article does not intend to suggest that the relationship between the state and prostitution is a simple oppositional one The Chinese state is not a monolithic subject; it is a complex institution with different stake-holders and a vast array of subjects who operate at different levels (national, provincial and local), who have a variety of interests and competing goals (such as disease prevention versus law and order versus income generation). While the dominant state discourse of prostitution has shifted, local law enforcement may not necessarily follow suit. In fact, scholars on prostitution in China have observed a pattern of private and public collusion in the operation of the entertainment industry, and the selective and discriminate enforcement of national law against sex workers working in different venues. In some instances government officials are major patrons of the sex industry in China, and many local governments encourage the development of the entertainment industry as a means of attracting investment and consolidating their legitimacy. This results in government and police protection for some well-connected entertainment venues, and crack-downs on others in order to be seen to comply with the political order from central government. When selective police enforcement of national orders on prostitution is practised, the most vulnerable section of the sex industry, such as drug-using sex workers and streetwalkers, often become the prime target of police arrests.Footnote 31

Beyond State Discourses of Victim and Victimizers: The Live Realities of Sex Workers in Post-Socialist China

Sex work arises under specific structural conditions of industrialization, urbanization and rapid rural-to-urban migration.Footnote 32 Although most sex workers face formidable structural constraints in both their work and personal lives, they cannot simply be construed as victims. The victim perspective is flawed because it ignores the agency of sex workers that manifests in their continued efforts to minimize the health, physical and emotional risks associated with sex work, their entrepreneurial efforts to maximize profits, their collective endeavours to formulate a counter-discourse challenging the cultural bias against them, and the novel strategies they deploy to manage a stigmatized identity.Footnote 33 The profiles and lives of our 245 respondents provide further evidence of sex workers as agents who navigate on the fringes of society in post-socialist China. Their agency is not only reflected in their role as breadwinners for their families and in their decisions to enter prostitution, but also in the numerous strategies that they devise in order to avoid contracting HIV.

Our research site was a medium-sized city (population 610,000) in south-western China. The research team identified 171 establishments providing commercial sexual services in the area. These included 63 hair salons, 35 karaoke bars, 19 beauty salons, 12 saunas, 12 massage parlours, 3 night clubs, 22 hotels and 5 hostels. Three locations where streetwalkers solicit business were also identified. With the assistance of outreach workers from an HIV intervention project sponsored by the UK Department for International Development, the research team (the author and five female outreach workers trained by the author) visited 114 entertainment venues and successfully completed in-depth interviews with 45 sex workers between 2003 and 2007. We also conducted two focus groups with over 30 frontline workers in intervention projects. In addition, a questionnaire survey of 200 sex workers was conducted in 2005.Footnote 34

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic background of the 200 respondents from the survey. The mean age of the respondents was 25. Three-quarters of them were migrant workers (69 per cent intra-provincial and 6 per cent inter-provincial). Among the migrants, the median length of stay at the site was four months. Over 60 per cent had secondary school education or above. Around 70 per cent had acquired other work experience before becoming involved in sex work. Around 40 per cent of the women had a primary sex partner and an equal percentage had children. Twenty per cent were divorcees. Around one-third (27.5 per cent) were one of the main carers of their children and 11.5 per cent were their children's sole carer. Around 70 per cent sent remittances home regularly. Over one-third said that they were the sole economic provider for their families. Nearly all (97 per cent) maintained regular contact with family members. Slightly more than one-tenth (11.1 per cent) were drug users. Over 60 per cent were under severe economic pressure. With respect to entrance into sex work, nearly 80 per cent were introduced by relatives, neighbours or friends.

Table 1: Socio-demographic Characteristics of Sex Workers Surveyed

As the figures show, most women had some education and previous work experience in other fields. Far from the trafficked, abducted or kidnapped victims formulated by the state and media discourses, all except three were connected to family networks even after becoming sex workers. Economic factors rather than coercion were the main reasons why women started doing sex work. The following narratives provide a glimpse of these economic factors.

Doing this work is all for a living (weile shenghuo 為了生活). My son is 12 years old; my mother is 69 and my father 72. My ex-husband gambles and visits prostitutes. I would be happy if he didn't try to extract money from me. I used to work in a factory, but the wage was only 300–400 yuan. It was hardly enough (genben bugou 根本不够). After paying for my son's school fee and giving some money to my parents, I didn't have anything left … but my son has an ulcer (liuzi 瘤子) that big [gesturing the size and position of the ulcer] on his left leg. I need to save money for his surgery. We have a mud house (niba qide fangzi 泥巴砌的房子), not a brick house (zhuanfang 磚房) and it looks as if it will collapse any time (dou yao dao de le 都要倒的了) … I need money to fix it … My parents are old. Old people get sick often, you need to pay for their medicine, and when they pass away, you need money to bury them, you can't just wrap them up in a mattress (xizi 席子)! (interviewee 4, streetwalker).

The engagement of this respondent in sex work was conditioned by dramatic economic and social transformation in the rural areas, which have altered opportunity structures in the job market, the value system, family structure and the role of the state in basic welfare provision. While there are more job opportunities for individuals, jobs for rural women are often low-end ones with wages that are hardly enough to make ends meet. Divorce rates are increasing and many men refuse to maintain their children after divorce. The reduced role of the state in the provision of education, health and old-age care means that families, particularly women, are forced to shoulder these burdens on their own.Footnote 35

For drug-users, sex work can become a means of survival. Although the provision of state subsidized methadone represents a great improvement in the state's handling of drug problems, current drug policy pays relatively little attention in helping ex-addicts to reintegrate into society.Footnote 36

Before I worked [sex work] because I needed money to buy drugs (maiyao 買藥). Now my husband and I both use methadone. It costs at least 600 yuan a month, and then we need money for food and rent. The minimum living cost (shenghuofei 生活費) is 1,500 yuan. We don't have work. We get some social security (shebao 社保), which is 140 yuan a month … That is why I need to do this [sex work] (interviewee 39, drug-using streetwalker).

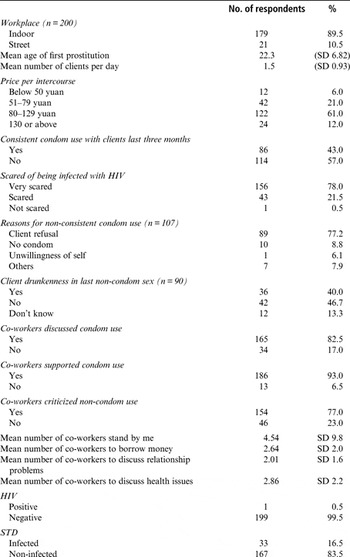

Turning to working conditions, 10 per cent of the women surveyed were streetwalkers (Table 2). The majority (89.5 per cent) worked indoors. The mean age of first sexual transaction was 22 years old. The mean number of clients per day was 1.5. Around 6 per cent of our respondents earned less than 50 yuan per intercourse. This group were all streetwalkers and would fit into tier 6 (jienü) of Pan Suiming's eight-category classification of sex workers in contemporary China.Footnote 37 Around 82 per cent charged above 50 but below 130 yuan per intercourse, and these were predominantly women working in hair salons, beauty parlours, bathhouses and saunas. They would fit into tier 5 (dingdong xiaojie) of Pan's classification. The remaining 12 per cent charged over 130 yuan per intercourse. This group all worked in karaoke bars and night clubs, and they would fit into tier 3 (santing) of Pan's schema. These figures suggest that the majority of our respondents were on the lower to middle end of the sex work spectrum.

Table 2: Working Conditions of Sex Workers Surveyed

With respect to the profiles of sexually transmitted infections, 0.5 per cent of our respondents were found to be HIV positive and 16.5 per cent were infected with a sexually transmitted infection. Nearly 80 per cent said that they were very scared of being infected with HIV. Despite their concern, only 43 per cent said that they had always used a condom with clients in the past three months.Footnote 38 Among those who did not always use a condom, around 77 per cent said that client refusal was the main reason. Around 20 per cent cited client drunkenness as the main reason for the last non-condom commercial sex.

This group of women was extremely vulnerable to client-perpetrated violence (Table 3). Over two-thirds of the respondents (68.4 per cent) reported that they had experienced some form of abuse from clients in the previous year. Among them, 63.5 per cent reported verbal abuse and 32 per cent reported physical violence (26.5 per cent were pelted with objects/pushed/shoved/grabbed/slapped, 15.6 per cent were hit with fists or bitten, 8.6 per cent were threatened with a weapon, 10.1 per cent were choked, 6.5 per cent were attacked with a weapon). With regard to sexual violence, a staggering 48.5 per cent were victimized by at least one form of sexual violence: 33.5 per cent were threatened into providing oral sex, 20.5 per cent were forced (forced is defined as the use of physical violence) to have oral sex, 8.5 per cent were threatened into providing anal sex, 7 per cent were forced to have anal sex, 33 per cent were threatened into having sex when they wanted to terminate the transaction, and 23 per cent were forced to have sex when they wanted to terminate the transaction.

Table 3: Client-perpetrated Violence against Sex Workers in the Last Year

The finding that the responsibility for the practice of unsafe sex lies mainly with clients contrasts strongly with state discourse which depicts sex workers as victimizers who are responsible for the spread of STI, and highlights the gender bias in this discourse. In fact, these women are exposed to the risk of STI because of men who place their own sexual pleasure above the health and well-being of their sex partners.

After a sex worker gains knowledge about HIV/AIDS, even if you don't give them condoms they will buy condoms themselves. Whether you have rice to eat or not is a more important problem (chifan wenti geng zhongyao 吃飯問題更重要).Footnote 39 If clients refuse to use condoms, they [sex workers] have no other ways but to accept. It is mainly a problem of clients (zhuyao shi piaoke de wenti 主要是嫖客的問題) (frontline worker, AIDS intervention project).

The prostitute as victimizer discourse not only overlooks the role of clients in safe sex practice, it also ignores the complexity involved in condom negotiation. Condom negotiation is not only about HIV knowledge and attitudes of sex workers; it also involves an array of actors, including their clients and the gatekeepers of entertainment venues, such as owners and managers. It is also shaped by cultural and structural factors beyond women's control, including gender norms of sexual negotiation, norms of trust and intimacy, poverty, gender inequalities, social attitudes towards sex work, and government policies.Footnote 40

Women's Strategies for HIV Prevention

Confronted with multiple health and physical risks at work, our respondents have devised novel strategies, such as screening, checking, vaginal douching, self-medication and negotiating condom use with clients, to protect themselves from STI. Client screening based on certain socio-demographic and behavioural markers is regarded as essential in order to reduce exposure to certain occupational hazards, including client denial of payment liability, perpetration of violence, forced unprotected sex and exposure to STI. Checking the genitals of clients for signs of abnormality and STI is another protection strategy women interviewed commonly use. By offering to help wash the genitals of a client, women take the opportunity to make a thorough examination of the client's sex organ before continuing the transaction. All of the 245 respondents interviewed reported purchasing disinfectant from pharmacies to cleanse their vaginas after each sexual transaction.

With increasing understanding about the transmission of HIV, many sex workers have learned that the above strategies are ineffectual methods for preventing HIV and cannot be a substitute for consistent condom use. They have therefore deployed strategies to persuade recalcitrant clients to use condoms.

If a client refuses to use condoms, I will say some flattering comments … flirting works wonders (interviewee 20, hair salon).

I will say, “What will happen if you get a disease and pass it to your wife?” I tell them they are out to have fun, not to get sick (interviewee 2, karaoke bar).

They [clients] complain that there is no flesh (mei de ganjue 沒得感覺) after using a condom. They said it was like wearing socks to wash your feet (chuan qi wazi xijiao 穿起袜子洗腳) … I will say that using a condom can prolong the time of love making (interviewee 19, night club).

I scare them [clients] by telling them that thousands of people have died of AIDS (interviewee 11, hair salon).

If a client refuses to use a condom … I say okay, if you don't care that I may have AIDS (interviewee 17, streetwalker).

The above quotations show the diversity of discursive tactics used by women. These included providing information about the health risk of STI and HIV/AIDS, their routes of transmission, the protection provided by condoms, the responsibility of men to protect their wives from STI, and the positive role of condoms in prolonging the time of love making. Although these discursive tactics do not always work, they demonstrate the resourcefulness and agency of our respondents and their willingness to practise safe sex to protect their own and their clients’ health.

The Consequences of State Control Tactics on HIV Prevention

Official discourse often justifies intensified control of prostitution on the ground that the state is forced to intervene because of the increased threat of venereal diseases. In spite of this ostensible justification, our data suggest the reverse effect: the Chinese state's intensified control and arrest of sex workers since the late 1980s has become a structural obstacle of safe sex practices. Repressive measures undermine the supportive professional networks of sex workers, increase economic pressure on them and increase their exposure to client-perpetrated violence. These negative consequences may in turn weaken the ability of sex workers to negotiate condom use with clients, and exacerbate their vulnerability to venereal diseases, including HIV/AIDS.

Sex workers working in the same establishment or location often share food and living quarters, and spend their waiting time chatting, playing mahjong, knitting and watching television together. These activities provide the basis for the development of a sense of community. The solidarity of such informal networks is further strengthened by native ties that channel women to work in the same establishments. For example, in our survey, the respondents said that on average they could count on between two and three friends working in the same workplace to lend them money in times of financial crisis, two friends to discuss relationship problems, and nearly three friends to provide information on STI. These informal networks also serve as conduits of information, and agents of social support that enhance women's ability to insist on condom use with clients and reduce their exposure to HIV-related risk behaviour.Footnote 41 Information about effective means of STI and HIV prevention, proper ways of applying condoms, strategies to prevent condom failure (slippage and breakage during intercourse) and methods to screen out potentially violent clients or clients who refuse to use condoms is circulated through these networks. For example, in our survey, 82 per cent of respondents said that their co-workers discussed condom use, 93 per cent said that their co-workers supported each other to use condoms with clients. Data from in-depth interviews also confirm the positive role of these informal networks.

We tell each other which one [client] was rude (xiong 兇), which one [client] was long (cha 長) [penis], which one last night refused to use a condom (bu dai tao 不帯套) (interviewee 3, hair salon).

That client had gone too far (tai gufen 太過份). He was very drunk, refused to use a condom, and slapped the xiaojie (小姐, a euphemism for sex workers). The owner (laoban 老板) was not there, so we [the other sex workers] argued with him and forced him to pay the bill and to compensate the girl 200 yuan (interviewee 31, night club).

I live with other girls. Many clients know that we do business and have money and will want to rob us. Sticking together is safer. If there are problems, for example clients refuse to pay or use condoms, we help each other out (huxiang bang yixia 互相幫一下) (interviewee 20, streetwalker, also peer-educator).

Furthermore, such networks are agents of socialization and social control.Footnote 42 In our survey, over 70 per cent of respondents said that their co-workers criticized sex workers who did not use condoms with clients. A study in China showed that women working in establishments with established norms of condom use were less likely to experience condom slippage and breakage.Footnote 43 The authors argued that this was because women working in establishments with an established norm of condom use may receive training on condom use skills from their co-workers. Secondly, they may also be subjected to greater peer pressure to enforce consistent and correct use of condoms.Footnote 44 In establishments where all the women use condoms with clients, non-condom sex may be regarded as a lapse of the occupational code of conduct and hence be condemned, criticized or ridiculed.Footnote 45 Finally, clients visiting establishments with an established condom-use norm may feel a greater need to be compliant with the discourse of safe sex.Footnote 46

The formation of these networks, however, has been hampered by frequent police raids and arrests.Footnote 47 After release, sex workers may not return to the same venue for fear of becoming the target of further police action. The fear of police raids and arrests is part of the reason why sex workers change work venues and locations frequently, thus greatly reducing the stability and strength of their networks with co-workers.

I just arrived a few days ago. I will stay at a place for one or two months and then go home … now the police keep a close eye on us. It is really dangerous. If caught, it is even more humiliating (geng meilian 更沒臉) … so basically I change venues every one or two months (interviewee 16, sauna).

Our survey showed that women on average stayed in the same establishment for four months. The rapid turnover of women undermines the HIV prevention work of health personnel and outreach workers, because it creates great difficulties for outreach workers trying to build up a stable and trusting relationship with women.

Outreach work is very difficult. The lower the class (dangci 檔次) [of sex workers], the more suspicious (jiebei 戒備) they are towards us, probably because lower-class sex workers like drug-using sex workers and streetwalkers are often the target of police arrests. We need to let them know that we are not the police, we will not harm (weihai 危害) them … They worry that we are undercover police (gong'an jiaban 公安假扮) … Even if we give them money to talk to us, they still refuse … The only way to gain their co-operation is to visit them once or twice a week, to say hello and give them some small presents, and to slowly build up the friendship (pengyou guanxi 朋友關係) … The problem is that because of so many raids and crackdowns, the chance that we will find them again the next time when we return (huifang 回訪) is low … (frontline worker, AIDS Intervention Project).

Police raids and arrests also increase the economic pressure of sex workers, in particular drug-using sex workers and streetwalkers.Footnote 48 Studies in various parts of China suggested that around 10 per cent of sex workers are drug users.Footnote 49 These women face tremendous economic pressure because they need to earn enough money each day to support their drug habit.

He asked me my price. We were still bargaining … He said he would give me 50. He said he would not use a condom. I thought that maybe I could persuade him to use one after we arrived at the guesthouse. Yet he insisted on not using a condom. He said that it was uncomfortable. I didn't have any money at that time. If I still didn't get any money, I would definitely suffer the pain of craving (fa duyin 發毒癮) (interviewee 39, streetwalker).

In a climate where competition for clients is already intense because of the continuous supply of women from rural areas, police raids scare potential clients away, seriously interrupt the livelihood of women and put these women in an even more powerless position in negotiating safe sex with customers. In fear of losing their customers and suffering the pain of craving, women often succumb to pressure to have unsafe sex:

Competition is fierce … The police … are everywhere. How can we find business? If there is business, we need to take the opportunity (zhuajin jihui 抓緊機會) … even if they [clients] refuse to use condoms … If we don't make use of the time when the police are not around to do business, the police will return soon (interviewee 19, streetwalker).

Some customers don't use condoms. They stay for [the intercourse] a few minutes. They say using a condom would take longer time. They are afraid of the police (interviewee 23, streetwalker).

The fines imposed by police once sex workers are arrested directly increase their operational cost. Many women incur debts from owners and managers of the establishments where they work because they need to borrow money to pay for police fines. The average price per transaction for a woman working in a hair salon is around 80 yuan, from which she earns 50 yuan and the owner/manager 30 yuan for commission. The police usually demand fines between 2,000 and 5,000 yuan. This means that a woman has to serve between 40 and 100 clients to pay back a loan that she borrows to cover a fine. Taking the mean number of clients per day in the research site, this means that a woman will have to work for between one-and-a-half and three months to repay a police fine debt to her owner/manager. This indirectly increases the control that managers and owners have over sex workers, and reduces their ability to resist pressure from owners/managers to accept clients who refuse to use condoms, or clients who agree to pay a higher price for non-condom sex.

Client-perpetrated violence is an obstacle to the practice of safe sex because it may be directly used to make sex workers comply with unprotected sex, or it undermines the control sex workers have over enforcing the contract.Footnote 50

We agreed 50 [approximately US$6] for one [sex] … but then he wanted me to provide oral sex … I didn't want to … he jumped on me and grabbed my head and forced his penis into my mouth … no matter how hard I struggled, I couldn't get rid of him … I was infuriated because he ejaculated into my mouth … I felt so disgusted that I vomited … Then I wanted to go … He said it was just oral sex, he hadn't had the real one … he refused to give me money … when we were to have [vaginal sex] I asked him to put on a condom … he refused and threatened to ejaculate into my mouth again … I threatened to bite [his penis] but he said if I dared he would kill me right there … (interviewee 36, streetwalker).

Before we started, he asked if it would be okay if we didn't use condoms, I said no. But then when we started, he just pinned my hands down and entered [pushed his penis into her vagina] (interviewee 16, sauna).

The illegal status of sex work means that sex workers are unlikely to report violent crimes to the police.

This work is illegal. How can we seek help from the police? We worry that they will arrest us … Plus some of the police are rotten … what they want is to sleep with us … without paying (interviewee 36, streetwalker).

The police are a threat; I will never rely on them. Calling the police is like dragging yourself into fire (interviewee 16, sauna).

Because sex workers are afraid to report violent crimes to the police, perpetrators of violence are emboldened because they can be sure of immunity. A respondent recounted how, after raping her, her client boasted to her that he would never be arrested by the police.

He [the rapist] said “you are a woman for sale (waitou mai de 外頭賣的). At most the police would only treat the case as one of refusing payment liability (dang de shou bu liao qian 當得收不了錢) … Today I did not take your life (meiyou yao ni de ming 沒有要你的命), even if I kill you, nobody will care.” I guess he was right. Even if I call the police, when they hear that I am a xiaojie, they would probably think that I deserve that (huogai 活該) (interviewee 8, streetwalker).

The illegal status of sex work in China and intensified police crackdowns increase the suspicion of sex workers towards the police and their fear of being arrested. This in turn inhibits sex workers from seeking police help in order to deal with violence, and increases the vulnerability of sex workers to violence. Sexual violence in turn exacerbates women's risk of contracting HIV/STI because most sexual violence occurs in contexts without the use of condoms.Footnote 51

Conclusion

Historical analysis of prostitution in Italy, Great Britain, the United States, France, Argentine and China all show that concerns of venereal diseases were one of the major motivations behind the institution of a regulatory regime and tightening control of prostitution.Footnote 52 Mirroring these historical patterns, this article suggests that the crisis of AIDS and the rationale of public health have prompted a shift in state discourse from sex workers as victims to sex workers as victimizers who spread diseases. The victimizer perspective has in turn provided public security a de jure reason for forcefully intervening against prostitution in post-socialist China. Our data not only show that the victim perspective is fundamentally flawed, but also reveal the grave defects of the victimizer discourse. Furthermore, they question the effect of punitive measures in helping to combat the spread of STI.Footnote 53 Our data suggest that repressive control measures against sex workers undermine the supportive professional networks of sex workers, increase economic pressure on them, and increase their exposure to client-perpetrated violence. These negative consequences may weaken the ability of sex workers to negotiate condom use with clients and aggravate their exposure to HIV risk. Our data thus suggest that state control of prostitution may in the end exacerbate the very problem the state seeks to address.

Instead of locating prostitution in post-socialist China within the broader social milieu of rural underdevelopment in the midst of rapid economic modernization, the Chinese state views it as a “vice” and sex workers increasingly as vectors of diseases. Studies in other countries have demonstrated that interventions that encompass three elements – respect for the human rights of sex workers, using the principles of harm reduction to address the structural obstacles of safe sex practices, and championing community empowerment by acknowledging the agency of sex workers – are often more effective in increasing the rates of safe sex practice, health promotion and disease reduction.Footnote 54 In order to use innovative policy initiatives to promote safe sex practices among sex workers and protect the health of this group of women as well as the general public, the post-socialist Chinese state thus needs to thoroughly re-examine its existing policy and its underlying assumptions.