Parental preferences for sons over daughters and technologies for sex-selective abortion have created the so-called “missing women” problem. Researchers claim that up to 100 million girls and women are “missing” worldwide – with strong adverse consequences for society. We revisit the empirical evidence for this problem in China, the country with the largest number of missing women. While nearly 15 million girls born in the 1980s and 1990s were originally believed to be missing according to census data collected in 2000, more than half of them re-emerge in more recent statistics. The reason is the extensive underreporting of (newborn) girls during the 1980s and 1990s. Parents may decide to postpone registration in response to economic factors (penalties associated with the one-child policy), but they may also intend to permanently hide their daughters from public view. We argue that many parents may have decided to hide their daughters from the census, but then changed their minds in response to recent policy changes encouraging truthful reporting. Important policy challenges remain. Since unregistered children can hardly access public services (for example, education and healthcare), they are severely disadvantaged compared to their registered peers.

Distorted Sex Ratios

Nobel prize winner Amartya Sen was the first to draw attention to the missing women phenomenon. Based on a comparison of measured sex ratios and “natural sex ratios,” the world was approximately 100 million girls and women short.Footnote 1 Later studies have updated Sen's estimate, in upward and downward directions, but his basic observation remains undisputed.Footnote 2 In many countries, especially in South Asia and West Africa, sex ratios are severely distorted. This is believed to have consequences for marriage markets,Footnote 3 (mental) healthFootnote 4 and crime.Footnote 5

China is the country with the largest number of missing girls and women. According to the 2000 census, the Chinese sex ratio was 1.23 in 1999, so 123 boys were born for every 100 girls. In some provinces, sex ratios were more distorted, reaching peak values of up to 1.36. This may be compared to the natural sex ratio, which is in the range of 1.02–1.05. For the period 1980–1999, approximately 15 million girls were missing according to the 2000 census.

The one-child policy (OCP) was an important factor shaping the Chinese missing women problem. The government's attempt to regulate fertility has prevented the birth of many millions of children;Footnote 6 however, in combination with strong parental preferences for male offspring, it has also contributed to distorted sex ratios. After ultrasound technologies became widely available, sex ratios started to increase, especially among those ethnic groups whose fertility was restricted by the OCP (for example, the Han Chinese).Footnote 7 In pursuit of a son, many households decided to have an abortion if their first child was a daughter. Or so it seemed.

The Re-emergence of Missing Women

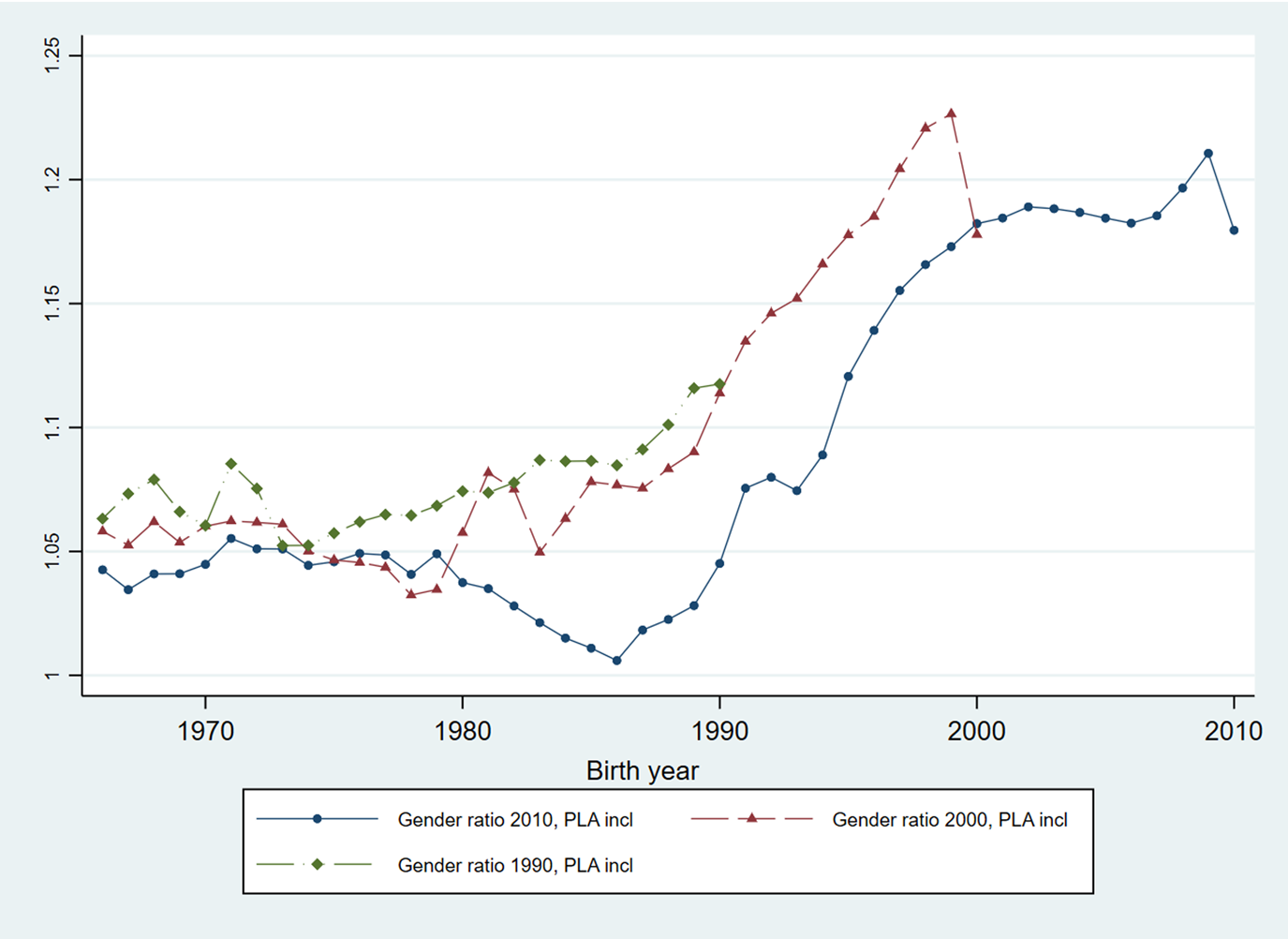

The most recent Chinese census, undertaken in 2010 and published in 2011, contained a major surprise. Compared to sex ratios calculated according to data from the 1990 and 2000 censuses, sex ratios were adjusted downwards for all cohorts born between 1980 and 1999. Importantly, the magnitude of this adjustment is massive. This is evident from Figure 1, which summarizes sex ratios for different age cohorts based on three different censuses, undertaken in 1990, 2000 and 2010. Three important observations can be made.

First, according to the 2010 census there is little evidence of distorted gender ratios during the 1980s. This stands in contrast to analyses based on earlier censuses, but it makes sense. Although ultrasound technologies started to spread during the 1980s, the great majority of Chinese households in the countryside could not access these technologies at that time.Footnote 8 Prenatal sex selection and differential abortion should have had little impact on Chinese sex ratios in the 1980s.Footnote 9 Instead, the OCP may have improved the nutritional status of girls in one-child families owing to a well-known quantity–quality trade-off. Consequently, measured sex ratios during the 1980s are among the lowest in the history of the People's Republic of China.

Second, the 2010 census indicates that sex ratios became increasingly distorted during the 1990s, as access to prenatal gender diagnosis improved. Changes in the number of missing girls correspond with the diffusion of ultrasound technology, which presumably lowered the cost of effectuating a preference for boys. In 1999, the average sex ratio was 1.17, which differs markedly from the natural rate.

Third, and most importantly, there is a large “gap” between sex ratios for 1980–1999 cohorts according to the 1990 and 2000 censuses, and sex ratios for these same cohorts according to the 2010 census. Earlier estimates of the number of missing women born between 1980 and 1989 appear to be overestimates of the actual number of missing women. Assuming a normal sex ratio for this age group is approximately 1.02–1.03, 4.55 million girls were missing in the 1980s and some 10.4 million girls in the 1990s.Footnote 10 Performing the same analysis, but now based on the 2010 census data, the number of missing girls falls to 200,000 in the 1980s, and to 6.3 million in the 1990s.

These are still large numbers that can be potentially disruptive for local marriage markets and a cause for concern and alarm. However, the missing women problem appears less pressing than initially perceived. By comparing the 2000 and 2010 census data, we “retrieve” no less than 8.4 million girls who were earlier considered to be “missing”: 4.3 million in the 1980s and 4.1 million in the 1990s. The underreporting of girls and young women in the 1990 and 2000 censuses accounts for most of the missing women problem. Migration cannot explain the patterns in these data, as Figure 1 is based on national statistics. Migration flows within China, from countryside to urban centres, surely influence sex ratios at the local or provincial level, but they cannot matter at the aggregate level where one province's “loss of men” is another province's gain.

Registration of Girls

The importance of underreporting versus sex-selective abortion has received some attention in the literature. Gender biases in reporting emerge if parents register their firstborn if it is a boy but choose not to register it if it is a girl.Footnote 11 This makes sense in the context of the OCP if parents want to keep open the option of having a registered son.

Hukou 户口 registration is an important issue in China. It provides an individual with access to public services such as healthcare, education, welfare, and so on. Individuals without a hukou do not qualify for any public support and cannot even register for public transport passes.Footnote 12 Censuses are also conducted based on hukou registration.

There are two possible scenarios that may explain the non-registration of liveborn girls. First, parents may decide to postpone hukou registration – most likely until the girl should enrol in junior high school (usually at 13 years old). Parents may delay registration until they are able to pay the fine associated with reporting out-of-plan births. Second, parents may not plan to register their daughters at all, hiding them permanently from the government. It is, of course, difficult to hide young children in a small community setting, and local officials are typically able to observe these children.Footnote 13 However, local officials may not report these out-of-plan births since their incentives may be aligned with the parents – they will want to report as few deviations from top-down plans as possible, and are unable or unwilling to force the parents, who are typically co-villagers with strong social ties, to pay the financial penalty.

Distinguishing between these two scenarios is not easy but doing so may shed light on an important question: why did so many girls re-appear in the 2010 census? Can this outcome be explained by the desire for delayed registration, or did parents who intended to not register their daughters at all suddenly change their minds?

Delayed Registration of Girls

Delayed registration was proposed by Yaojiang Shi and John Kennedy.Footnote 14 They consider girls emerging in later censuses as delayed registrants, arguing that families may decide to register their daughters with a delay of several years – until these girls reach school age.Footnote 15 Yong Cai argues that if delayed registration explains under-registration, then missing girls should show up later.Footnote 16 Additional females should show up in national education statistics, which should be less distorted than earlier census data. However, Shi and Kennedy show that these education statistics are flawed and incomplete and, until 2010, failed to include migrant children.Footnote 17

Delayed registration likely explains part of the discrepancy between sex ratios in the 2010 and 2000 censuses. However, delayed registration is unlikely to provide a complete picture. If registration is delayed until girls reach school age, then the sex ratio of older cohorts in our sample should be less distorted than that of younger cohorts. Assume that children go to school out of their village when they turn 13 and need to have hukou then. In the 2000 census, the sex ratios of the pre-1987 cohorts should be more balanced than the sex ratios of the post-1987 cohorts. If delayed registration explains (temporarily) distorted sex ratios, then the discrepancy between sex ratios in the 2010 and 2000 censuses should be trivial for the pre-1987 cohort, but significant for 1987–1999 cohorts.

However, this is not evident from Figure 1. The sex ratios taken from the 2000 and 2010 census are almost parallel during the 1980s and 1990s. Moreover, if delayed registration was the reason for the difference in sex ratios between the 2000 and 2010 censuses, then there should also be a gap in sex ratios between the 2010 census and the 1 per cent national population sample survey of 2015. But Figure 2 shows there is no systematic difference in sex ratios between these two samples.

Policy Changes

We speculate that the most likely explanation is a policy change in the implementation of the 2010 census. Hukou registration serves as the basis for population enumeration in China's censuses. As an important part of the preparations for the censuses, a hukou rectification is conducted by the police bureau beforehand to correct non-registration or misregistration. The Chinese government was becoming increasingly concerned about the problem of the non-registration of Chinese citizens, which is rooted in the contradiction throughout the 1980s and 1990s between the local Family Planning Office (FPO), which aims to control out-of-plan births, and the police bureau, which aims to register all people (all births) regardless of their status.Footnote 18 To resolve this problem and improve the quality of hukou registration data, an announcement was made leading up to the 2000 census proclaiming that: “residents without hukou owing to a violation of the one-child policy are allowed to register hukou during the hukou rectification before the census.”Footnote 19 However, many parents still had concerns since no promise was made regarding the confidentiality of hukou rectification data.

In 2010, the census authority made a concerted effort “to promise that information would not be passed to the birth control authority as a basis for fines, nor would the rectified fertility data be used for the evaluation of local government performance in family planning.”Footnote 20 This followed an amendment of the Statistics Law of the People's Republic of China in 2009. An important revision stipulated that data collected for the census could only be used for statistical purposes and not for the enforcement of laws and policies. Only anonymized data would be shared with other government branches, and confidentiality regulations stipulated that “users” of these data should be unable to trace back information to specific households.Footnote 21 Following the amendment, it was emphasized that “information [gathered] from the hukou rectification is not allowed to be used as the basis for administrative actions, citation or penalty.”Footnote 22

Policy changes were widely publicized and communicated to the public in the period preceding the census.Footnote 23 In some regions, such as Beijing, census takers signed agreements of confidentiality with households before collecting data. Equally important is the fact that local officials were aware of the policy change and were given incentives to encourage residents without hukou to register during the hukou rectification stage running up to the 2010 census. As the policy changes temporarily severed the link between hukou rectification and punishment for out-of-plan births, local officials more likely placed “the accurate enumeration and full coverage of the population as a high priority.”Footnote 24

Nonetheless, not all families registered their girls. However, as any “information learnt from the census about any individuals shall be kept confidential according to the Statistics Law,” girls and young women without hukou but identified by enumerators in the census were recorded as “population with undetermined hukou” and details were not shared with FPOs.Footnote 25 As a result, the number of people with undetermined hukou increased by more than 70 per cent between the 2000 and 2010 censuses.Footnote 26

In other words, we believe “statistics by law” is a key reason for the success of the 2010 census.Footnote 27 The Chinese government succeeded in convincing a majority of its constituency to provide truthful demographic information. Although this can hardly be statistically proven, we believe the discussion provides an important starting point for future enquiry and discussion.Footnote 28

Another interesting possibility emerges, which must be treated as conjecture until future data become available. To the extent that citizens remained either uninformed about the judicial amendment or unconvinced about the nature of the confidentiality message they received, it is possible that they continued to underreport their children. In that case, the 2010 census-based estimates of the number of missing women could still be an overestimate of the actual number of aborted girls.

Determinants of Re-emerging Missing Women

We also analyse the distribution of re-emerging missing women at the provincial level, which may help us to understand the determinants of underreporting of women. People have an incentive to underreport if their fertility is restricted by the OCP and if enforcement of that policy is limited (so that they are unlikely to be caught and punished). As shown in Figure 3, underreporting was especially common in provinces with few ethnic minorities and in rural areas. The reason is that the OCP allows exemptions for some ethnic minoritiesFootnote 29 and the enforcement of the OCP in rural areas was relatively weak.Footnote 30 So, underreporting was rare in the ethnic autonomous regions (for instance, Tibet and Xinjiang) and more urbanized areas (for instance, Beijing and Shanghai).

Figure 4 confirms the pattern, and regression analysis provides further support.Footnote 31 Both the percentage of ethnic minorities and the degree of urbanization significantly reduce the percentage of underreported women.Footnote 32 The link between re-emerging missing women and enforcement (targeting) of the OCP is strong and direct.

Policy Implications

Our findings have immediate and urgent implications for policy. The gradual abolishment of the OCP in 2015 implies that the problem of underreporting will become less important in the future. But this does not diminish the fact that there are many unregistered individuals born before 2015 who have stayed under the government radar until now. There are strong reasons to suspect that not all is well with these individuals.

As mentioned, unregistered children in China do not have a hukou. And while young children without a hukou may be able to benefit from locally organized schooling (through home tutoring and domestic care, or otherwise), this is not a suitable option for children who should enter secondary education. On average, unregistered girls are likely to suffer from a large shortfall of human capital. This will adversely affect their quality of life and their employment and marriage opportunities. Unregistered girls are socially and economically vulnerable.

The state should help these individuals to gain access to public services by investing in the formation of human capital. Examples include programmes that provide unregistered girls with access to the education levels they need to qualify for gainful employment. Such public investments may not only have decent rates of return from an economic perspective but may also reflect an opportunity for the state to take responsibility for and remedy a situation that is to a large extent an unintended side effect of the one-child policy.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the insightful comments of the editor and two anonymous reviewers. We would also like to thank our research assistant, Sihan Zhang, for her excellent work. All errors are our own.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical notes

Erwin BULTE is professor of development economics at Wageningen University. He is also Flagship leader of the Policies, Institutions and Markets (PIM) programme of IFPRI, and a research fellow at the department of land economy, University of Cambridge.

Chih-Sheng HSIEH is associate professor at the department of economics, National Taiwan University.

Qin TU is professor of economics at the Center for Innovation and Development Studies, Beijing Normal University at Zhuhai.

Ruixin WANG is assistant professor of economics at the School of Economics and Management, Harbin Institute of Technology, Shenzhen.