Studying political mobility outcomes under China's cadre management system provides critical insight into how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) functions as well as the composition of the Party elite. The nomenklatura system is a key mechanism that the centre uses to exercise control over the leading officials within the CCP and government bureaucracies.Footnote 1 It also governs the top leaders of China's largest and most strategically important state-owned enterprises (SOEs).Footnote 2 Top executive positions in the core state-owned companies, officially designated as “important backbone state-owned companies” (zhongyao gugan guoyou qiye 重要骨干国有企业), belong to the central nomenklatura list managed directly by the Organization Department of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.Footnote 3 Specifically, these top executive positions are: Party committee secretary (dangwei shuji 党委书记), general manager (zongjingli 总经理) or president (zongcai 总裁), and chair of the board of directors (dongshizhang 董事长), if one exists. Although core central state-owned company leaders are not civil servants (gongwuyuan 公务员), they possess the equivalent rank of a vice-minister (fubuji 副部级).Footnote 4

Scholarship posits that there is a “revolving door” through which central SOE leaders rotate routinely between state-owned industry and successively higher-ranked positions in the Party-state.Footnote 5 I evaluate this phenomenon by analysing an original biographical dataset for all core central SOE leaders serving between 2003 and 2012 during the Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 administration. In contrast to the existing literature, I find that the majority of those who left their posts ended their careers, entering retirement directly. Of those who continued their political careers, virtually all advanced through lateral transfers (pingji diaodong 平级调动) along three pathways with little overlap: top executive postings at other core central state-owned firms; government or Party provincial leadership positions; or leadership roles in government or Party organs at the central level. I also consider the underlying aims and the implicit hierarchy of these three career pathways as well as the attributes of those officials who followed these routes.

As more than 90 per cent of the core central state-owned company executives who advanced politically during the Hu Jintao administration were appointed to positions of equivalent formal administrative rank, this paper highlights the importance of lateral transfer. Current scholarship focuses primarily on promotion and the factors affecting its likelihood.Footnote 6 Lateral transfer might be assumed to be a homogenous category, given the lack of change in formal administrative rank. It is rarely considered as a political mobility outcome worthy of closer study. However, lateral transfer is a critical element in many individuals’ career trajectories, particularly for vice-ministerial ranked officials.Footnote 7 Moreover, it is a crucial mechanism by which the cadre management system develops, assesses and selects the next generation of Chinese political leaders.Footnote 8 Disaggregating lateral transfers not only reveals subtle changes in the influence of individual officials over the course of their careers, it can also illuminate fluctuations in the balance of power among political elites, Party and government agencies, and between the centre and localities.

Existing Research

Seminal scholarship on the cadre management system and Chinese officials’ political mobility did not address central SOE leaders. Instead, it detailed the cadre management system and its evolving processes of appointment, assessment, transfer, promotion and removal.Footnote 9 Scholars debated its institutionalization – the extent to which elite appointment, assessment and termination is defined and executed by statute – and implications for the Chinese political system's stability and future evolution.Footnote 10 Others highlighted the decentralization and recentralization of personnel authority between the centre and localities, studying the shifting power of appointment in successive nomenklatura and the broader oscillations in Party authority under Mao Zedong 毛泽东, Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 and Jiang Zemin 江泽民.Footnote 11 Parallel empirical studies revealed a demographic transformation from an older, less educated revolutionary cohort towards a younger, more educated and technically qualified official elite across Party, government and military organs.Footnote 12 With control of what would become China's largest SOEs still fragmented among government ministries amid debate over a future system for managing state-owned assets, none of these foundational works considered how their leaders were selected, their attributes, or where their careers led.Footnote 13

Yet, current research on Chinese officials’ political mobility also omits state-owned company leaders. Their absence is particularly conspicuous in the contemporary “red” versus “expert” debate – that is, whether and under what conditions political connectedness or performance affects the likelihood of promotion. In this debate, one body of scholarship contends that economic performance increases Chinese officials’ likelihood of promotion.Footnote 14 Another holds that political connectedness and patronage relationships (assessed by measures such as central government work experience, factional ties or central appointments for officials at lower levels of government) make promotion more likely.Footnote 15 Still others argue that performance matters more for the likelihood of promotion at lower levels of government and more administrative positions (such as provincial governor), whereas political connectedness possesses a greater impact at the central level and for politically charged positions (such as Party secretary).Footnote 16 As central state-owned companies are ostensibly corporate in nature and leaders of the core firms belong to the central nomenklatura list, their omission from this performance versus patronage literature is surprising.

Political science, legal and business scholarship specifically addressing Chinese central state-owned company leaders is growing but remains limited. A principal claim is that these individuals form a distinct elite group, the members of which rotate regularly between state-owned industry and Party and government positions, and whose representation in top leadership bodies such as the Central Committee is increasing.Footnote 17 Numerous studies posit that there exists a “revolving door” between the Party, government and state-owned industry in China, which is said to operate through repeated cadre transfers from state-owned business to the Party-state or vice versa, often to positions of successively higher administrative rank.Footnote 18 Other works highlight the nomenklatura system more broadly as a key institutional mechanism through which the CCP integrates and controls the largest SOEs.Footnote 19 Extant research includes qualitative and quantitative works that examine state enterprise managers’ career trajectories by industry, in China's largest non-financial state-owned firms, and in their publicly listed subsidiaries.Footnote 20

Although these studies open valuable inquiry into the political mobility of Chinese central SOE leaders, they exhibit several shortcomings. First, their empirical scope is limited. While examining individual company leaders or subgroups of top executives in specific industries is a critical step, these studies do not attempt systematic assessment of political mobility outcomes for central SOE leaders as a whole. Second, several studies pool together leaders of core and non-core state-owned companies as their subject of analysis, or combine within-company and after-company promotion as a single dependent variable.Footnote 21 However, this is not advisable since different bodies appoint the leaders for these two groups of state-owned companies, and also because the factors affecting intra-firm and post-firm promotion are likely to differ.Footnote 22 Finally, these works’ short timeframes cannot capture significant variation over time, which limits their ability to identify both systematic patterns and potential discontinuities.Footnote 23

Research Question and Data

Did central SOE leaders under the Hu Jintao administration rotate routinely between state-owned industry and successively higher-ranked positions in the Party-state? This study focuses on leaders of the core central state-owned companies because they belong to the central nomenklatura list managed by the Central Organization Department; executives of the other central SOEs are administered by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (guoyou zichan jiandu guanli weiyuanhui 国有资产监督管理委员会, hereafter referred to as SASAC). The term “leaders” here refers to individuals serving in one or more of the top three positions at the holding company level: general manager (zongjingli) or president (zongcai); Party committee secretary (dangwei shuji); or chair of the board of directors, if one exists (dongshizhang).Footnote 24 Within their companies, these executives possess the ultimate decision-making authority on matters ranging from investments to corporate strategy. While top leaders are supported by members of their leadership team (lingdao banzi 领导班子), their ranking, equivalent to vice-ministerial level, distinguishes them from other executives within their firms.Footnote 25

This paper examines the period between 2003 and 2012. The start year of 2003 is chosen to coincide with the establishment of SASAC. In that year, Chinese leaders advanced the process of separating the central SOEs from government ministries and other state organs by centralizing their administration under SASAC. The end year of 2012 is chosen because limiting the study to the Hu Jintao administration minimizes potential concern about discrepancies with the current Xi Jinping administration. Different regimes may exercise authority over personnel appointment in divergent ways, with differing goals for officials at various levels across the military, Party or government bureaucracies. Furthermore, changing policy priorities, such as fighting corruption or restructuring centrally-owned assets through government-directed mergers, also shape and interact with the approaches that different administrations take to cadre management.

This paper's analysis uses an original dataset of 864 leader–year observations for the top executives of the core Chinese central state-owned companies between 2003 and 2012.Footnote 26 Biographical information about these leaders’ backgrounds and their career trajectories was taken from their official CVs, which were available on company websites or publicly online, as well as from the Chinese Political Elites Database hosted by National Chengchi University.Footnote 27 This biographical information includes details about each individual's age, education, leadership tenure, number of years worked in a given firm before assuming a top executive position there, and prior work experience in other government or Party organs at central or sub-central levels. The following sections discuss how political mobility outcomes, biographical attributes, and these other factors are measured.

This study identifies four types of political mobility outcomes based on an individual's immediate next appointment: in position, promotion, lateral transfer, and termination. A state-owned company leader is considered in position if he has not yet been appointed to a subsequent post during a given calendar year. Promotion is defined as appointment to a position of higher formal administrative rank at the provincial or central level. Lateral transfer takes place when an individual is appointed to another position of equivalent formal administrative rank, in this case to another vice-ministerial ranked position. Termination occurs if retirement is stated explicitly as the reason for exit, which constitutes the vast majority of cases, or if an individual takes up a so-called empty position (xuzhi 虚职) or “retires internally” (neitui 内退), for example by serving as a head engineer within his company but no longer holding a formal leadership position. The few publicly reported cases of disciplinary investigations or violations are also categorized as termination, because the use of forced retirement for disciplinary purposes prevents discerning definitively between them.Footnote 28

This study also includes two key individual-level attributes: age and educational background. Age is particularly important for political mobility because of mandatory retirement ages for Chinese officials. Executives of the core central SOEs with the equivalent of vice-ministerial rank are required to retire at the age of 60.Footnote 29 Education is also significant for political mobility because executives with higher educational attainment or degrees in a technical field may be more likely to advance politically, in line with the Party's ongoing efforts to professionalize cadres. Education is defined as an individual's highest scholarly attainment: high school education, undergraduate degree, master's degree (MA), or doctoral degree (PhD).Footnote 30 Separate measures are also reported for master's or doctoral degrees in management and in technical fields, specifically engineering (gongke 工科) or a hard science (like 理科).

Leadership tenure is also included as a standard factor in studies of Chinese officials’ political mobility.Footnote 31 It is defined as the total number of years that an individual serves in one or more of the top three leadership roles at a particular core central state-owned company. It includes both joint appointments (in which a single individual holds one or more top leadership roles simultaneously) and consecutive top leadership roles (if a single individual serves consecutively in different top leadership roles or combinations of those roles).Footnote 32 There is no fixed term limit for the top executives of central SOEs, in contrast to other Party and government officials who do face formal term limits.Footnote 33 Longer leadership tenure may be either an asset or a detriment to political advancement: it may signal depth of leadership experience, or it may imply a lack of ability or indicate that one is coasting to retirement.

This study also includes the total number of years that an executive worked in a given state firm before assuming a top leadership position. Company experience may either help or hinder subsequent political advancement. Long-serving executives in a single state firm may be less likely to advance after their leadership tenure because they are seen as having narrow professional expertise and experience specific to that company or industry. On the other hand, executives who fought their way to the top over a period of years, even decades, may be viewed as experienced leaders better suited for lateral transfer or even promotion.

Finally, this paper considers whether core central state-owned company leaders possess previous full-time work experience in central government or Party organs. In theory, this experience could enable them to cultivate informal connections or greater familiarity with performance assessment processes, which in turn might impact their subsequent political advancement. Time spent working at the centre may also make executives more responsive to, and likely to implement, central policies.Footnote 34 For central state-owned company leaders, however, work experience at the centre may have less impact than for local officials. Unlike local officials, who are distant from the heart of political power in Beijing, most central SOEs are headquartered in the capital and their leaders interact routinely with central-level government and Party authorities.

Changing Composition of Central State-Owned Company Leadership

Three key attributes are evident in core central state-owned company leaders’ backgrounds and career experiences between 2003 and 2012: significant advances in their professionalization through education; their emergence as a distinct group within China's top political elite; and their stable but relatively weakly institutionalized rates of termination. This section summarizes changes in the overall composition of the core central state-owned company leadership during this period. It then analyses the distinct pathways through which a minority of leaders advanced politically.

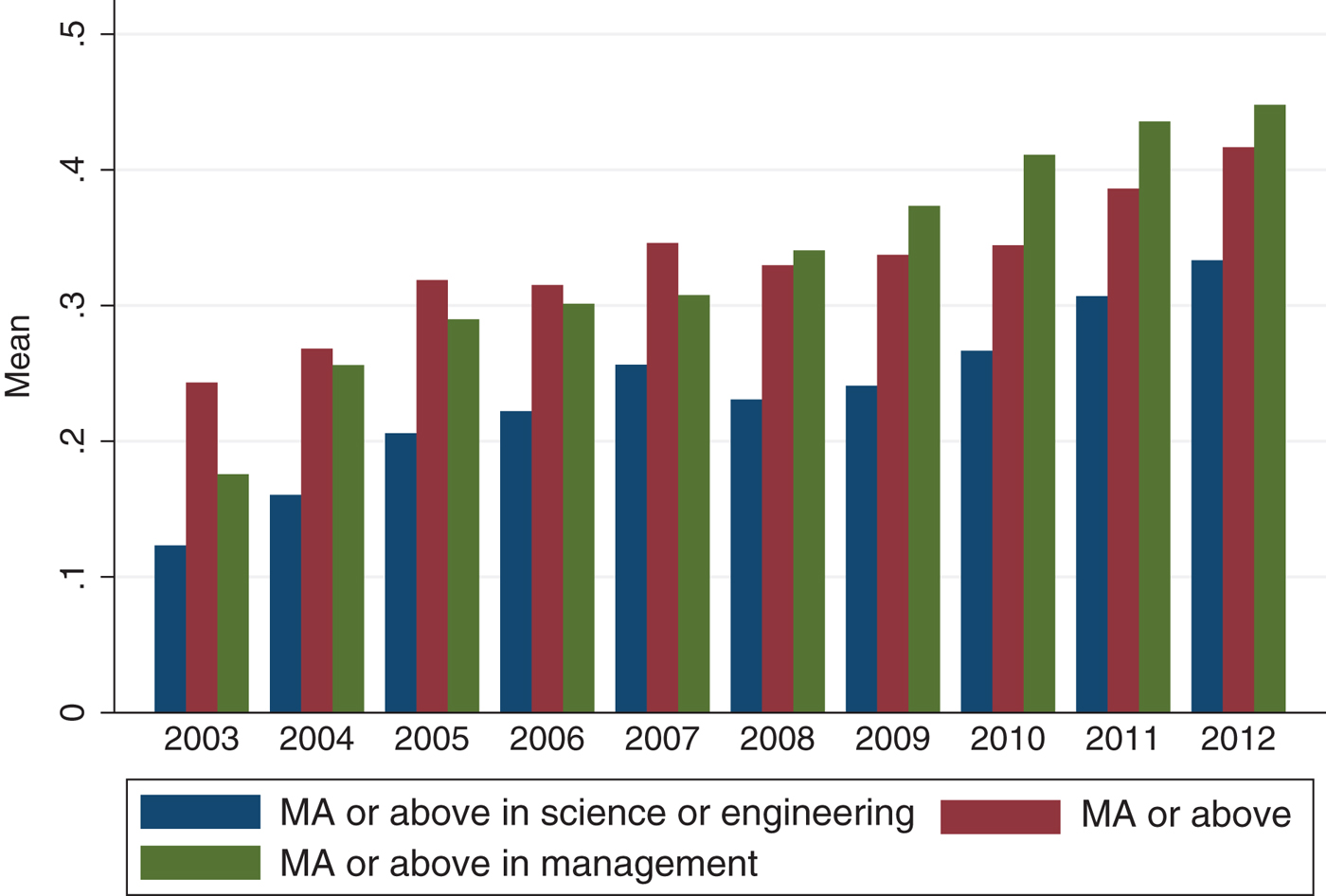

With only two exceptions, the top leaders of China's core central SOEs who served between 2003 and 2012 all had at least a college education (Figure 1). This level of educational attainment mirrors that of provincial governors and Party secretaries, and it accords with Party regulations that candidates for positions above the county level should possess a college degree.Footnote 35 The proportion of executives who held master's degrees or higher in engineering or science more than doubled from 12.3 per cent in 2003 to 33.3 per cent in 2012. At the same time, more individuals sought master's degrees in business administration (MBA) and/or PhD degrees in management; the proportion of executives with these qualifications jumped from 17.6 per cent in 2003 to 44.8 per cent in 2012. There was scant overlap between those with advanced degrees in science or engineering and those with higher degrees in management. This, together with the fact that numerous executives obtained MBA and/or PhD degrees in management during their leadership tenures, suggests that many sought deliberately to burnish their educational credentials in order to achieve political advancement.

Figure 1: Post-college, Advanced Science, and Management Educational Attainment, 2003–2012

Leaders of the core central state-owned companies emerged as a distinct, if not insular, group among top Chinese officials during the Hu Jintao administration. The majority were “state-owned industry careerists” who built their careers working in SOEs. In 2003, 69.3 per cent of serving executives had not worked previously in a Party or government position at the central level. By 2012, this proportion increased to 86.3 per cent. In 2003, 71.6 per cent had not worked previously in the provinces or municipalities. By 2012, this figure rose to 79.2 per cent.Footnote 36 At the same time, both the number of years that serving executives had worked previously in their firms and the average length of their leadership tenures increased steadily throughout the decade (see Figure 2). Years of work in one's firm before assuming a top leadership position rose from an average of 5.3 years for executives serving in 2003 to 8.1 years in 2012, while leadership tenures lengthened from an average of 3.9 years for leaders serving in 2003 to 5.6 years in 2012. Finally, SOE executives' political circulation was significantly less than that of other vice-ministerial ranked officials during the same period. Between 2003 and 2012, 4.3 per cent of core central SOE leaders were transferred laterally and .4 per cent were promoted, compared with rates of 8.7 per cent lateral transfer and 4.0 per cent promotion for executive vice-governors (vice-governors serving on a provincial standing committee).Footnote 37

Figure 2: Years Worked in Firm Before Leadership and Leadership Tenure, 2003–2012

Finally, most of the core central SOE leaders whose leadership tenures ended between 2003 and 2012 had their careers terminated, with the annual termination rate stable but mandatory retirement ages weakly enforced. During this period, 53.9 per cent of individuals who vacated their executive positions during this period had their careers terminated. Their mean age in the year of termination was 62 years old, compared to the average age of 53 years old for in-position executives during this period (see Figure 3). Annual termination rates declined from a high of 12.9 per cent in 2004 and stayed at 7.5 per cent or less for the remainder of the decade. However, the relatively high proportion of leaders serving over the mandatory retirement age of 60 demonstrates the weakly institutionalized, if stable, career termination of central SOE leaders during the Hu Jintao administration. Of leaders serving between 2003 and 2012, 10.1 per cent exceeded the mandatory retirement age of 60. While this proportion may appear low, it is in fact quite high compared with other Chinese officials. For instance, only one mayor and six municipal Party secretaries exceeded the mandatory retirement age of 60 between 2000 and 2010, constituting approximately 1 per cent of cases.Footnote 38 In every year between 2003 and 2012, less than 1 per cent of serving provincial Party secretaries exceeded the mandatory retirement age of 65; no provincial governors surpassed it during this period.Footnote 39

Figure 3: Age of Core Central SOE Leaders, 2003–2012

Three Career Pathways from Core Central SOEs

To executive leadership in another core central SOE

Among the minority of core central SOE leaders who advanced politically between 2003 and 2012, lateral transfer constituted more than 90 per cent of all appointments. During this period, 14 individuals were transferred laterally to leadership positions at another of the core SOEs.Footnote 40 As a group, they reflected core central state-owned company leaders as a whole in their age and with a lack of previous experience outside of state-owned industry. Their average age in the year of transfer was 53 years old; they ranged in age from as young as 46 years old (Ning Gaoning 宁高宁, transferred from China Resources Group to China National Cereals, Oils and Foodstuffs Corporation) to 60 years old (Fu Chengyu 傅成玉, transferred from China National Offshore Oil Corporation to China Petrochemical Corporation). Half had post-college educational attainment, with 35.7 per cent of the group holding advanced degrees in science or engineering; 42.9 per cent held a master's degree or above in management.Footnote 41 The majority had never worked previously in central government.Footnote 42 Apart from the previous service of Wang Jianzhou 王建宙 in the Zhejiang Bureau of Posts and Telecommunications, none possessed earlier work experience below the central level. Individuals following this career pathway worked a total of 2.8 years on average in the companies they led before assuming their executive positions and had leadership tenures of 4.9 years on average.

Multiple aims motivate the lateral transfer of executives from one core state-owned company to another. First, it can create organizational learning by bringing in individuals with successful experiences running other state firms. A second motivation is to limit the potential risk of departmentalism (benweizhuyi 本位主义) through intra-industry executive swaps.Footnote 43 For example, in 2008 Guodian Party secretary Li Qingkui 李庆奎 was shuffled to Huadian, while Huadian Party secretary and general manager Cao Peixi 曹培玺 was transferred to Huaneng. Yet another motivation is to facilitate planned consolidation of SOEs in a given sector. However, this aim does not appear to be significant between 2002 and 2012, as only two mergers impacting the core state firms with vice-ministerial rank occurred during this period.Footnote 44

Appointments to another core central SOE between 2003 and 2012 were all lateral transfers. They did not function as a “revolving door” with the Party-state, since these personnel moves occurred within state-owned industry itself. As of the end of 2012, only one of the 14 individuals was rotated outside of the core state firms.Footnote 45 Nor did appointment to another core central SOE act as a springboard for promotion: none of the 14 obtained ministerial rank during this period. Within this group, some variation existed in the combinations of positions they held and to which they were subsequently appointed.Footnote 46 Scrutinizing the differences between individuals’ top leadership roles held at time of transfer and those to which they were appointed suggests that implicit “promotions” occurred, even if their vice-ministerial equivalent ranking remained unchanged. One example is the appointment of general managers to joint general manager-Party secretary posts or Party secretary-chairman posts. Another example is lateral transfer to a larger core SOE in the same industry.

To provincial leadership

The second career pathway for core central SOE executives was lateral transfer to a Party or government provincial leadership position. Between 2003 and 2012, 11 individuals followed this trajectory.Footnote 47 As a group, they were distinguished by their relative youth and by more than half of the group's subsequent advancement to ministerial rank (see Table 1). Their average age in the year of transfer was a mere 49 years old. More than half had post-college educational attainment. Of these 11 executives, 27.3 per cent held advanced degrees in science and an equal proportion had earned a master's degree or above in management. Most were state-owned company careerists; only two of them had worked previously at the central level.Footnote 48 Individuals who followed this career pathway worked at their firms for a total of 4.5 years on average before assuming their executive posts and had leadership tenures of 5.6 years on average before their next appointments.

Table 1: Core Central SOE Leaders Transferred to Provinces Who Attained Ministerial Rank, 2003–2012

Source: Author's database

Note: Zhang Qingwei, appointed as acting governor of Hebei in 2011, already held ministerial rank from his 2007 appointment as chairman of the Commission for Science, Technology and Industry for National Defence.

Through lateral transfer to provincial government or Party positions, one of the Central Organization Department's principal aims is to cultivate officials with a breadth and depth of experience for potential future promotion. Individuals in this group stand out as both the most youthful and the most educated: more than half held master's degrees or higher, including in science or engineering. Transfer to a province or municipality therefore constitutes a deliberate diversion of promising younger cadres away from climbing the leadership ranks within state-owned industry: only three of the 11 individuals in this group had reached the position of chairman at their time of transfer.Footnote 49 And even for these three chairmen, their relatively youthful ages of 49, 50 and 52 at the time of transfer demonstrate that individuals belonging to this career pathway were just entering their prime decade of potential political promotion.

Appointment to provincial leadership positions during this period rarely functioned as a “revolving door” up to the centre or back into state-owned industry. Most of the core central SOE leaders who transferred to the provinces were still there in 2012.Footnote 50 It did, however, serve as a pathway to political promotion. Apart from China Commercial Aircraft Corporation Party secretary and chairman Zhang Qingwei 张庆伟, who already held ministerial rank, five core central SOE leaders were promoted after their appointments to provincial leadership posts (see Table 1). Some, like Wei Liucheng 卫留成 and Su Shulin 苏树林, were promoted almost immediately after their initial lateral transfers. Again, it is possible to assess implicit “promotions” by looking closely at the executive posts these individuals held at transfer and the provincial leadership positions to which they were appointed. Compare, for example, Chen Weigen 陈伟根 and Zhu Yanfeng 竺延风, both of whom were transferred in 2007 to Jilin province. Chen, formerly the chairman and Party secretary of China General Technology Group (Genertec Group) was appointed as a provincial vice-governor at the age of 52, while Zhu, previously the general manager of China First Automobile Group, was appointed as a provincial vice-governor and provincial standing committee member at the age of 46. Overall, given their rapid career advancement and relative youth – on average five years younger than executives appointed directly to the centre from state-owned industry – those who followed this career pathway appeared to be the best poised for future political rise.

To central leadership

The third political pathway for core central SOE leaders was appointment to a government or Party position at the central level. Between 2003 and 2012, 15 individuals followed this career pathway: 12 were transferred laterally and three were promoted.Footnote 51 As a group, they were relatively less educated, older, and had longer leadership tenures than core central SOE leaders overall. They also largely lacked previous experience at the central level. Those who were transferred laterally to the centre had an average age at transfer of 55; none had earned more than a college degree in a non-management field or held advanced degrees in science or engineering, although 54.5 per cent of them had earned a master's degree or higher in management.Footnote 52 They worked a total of 2.7 years on average in the companies they led before assuming their executive posts and had leadership tenures of 6.3 years on average. For the three individuals promoted to the centre, their average age at transfer was 54; two had post-college educational attainment, one had an advanced degree in science or engineering, and none had degrees in management. They worked a total of 3.0 years on average in their firms before assuming a top position and had leadership tenures of 6.7 years – the longest of any of the executives during this period. Only four of the 15 appointed to the centre had previous work experience at the central level.Footnote 53

Several objectives motivate appointment of core central state-owned company executives to positions at the centre. First, many were appointed to regulatory or ministerial positions requiring specific industry or technical expertise in the sectors in which they worked previously.Footnote 54 For example, China Eastern Airlines Party secretary Li Jun 李军 (2006–2011) was appointed as deputy director of the Civil Aviation Administration of China. Similarly, State Nuclear Power Technology Corporation general manager Wang Shoujun 王寿君, China Nuclear Engineering and Construction Corporation Party secretary and general manager Mu Zhanying 穆占英, and Datang Group Party secretary and chairman Liu Shunda 刘顺达 were transferred to the Board of Supervisors for Key Large State-Owned Enterprises (guoyou zhongdian daxing qiye jianshi hui 国有重点大型企业监事会) to monitor firms in their areas of previous industry experience. Particularly for those not yet approaching retirement age, appointment to the centre may reflect the Central Organization Department's intention to broaden their experience beyond state-owned industry as part of a grooming process for continued political advancement. But for many, it marked the last chapter of their official careers before retirement.

For core central state firm leaders appointed to the centre between 2003 and 2012, there was limited evidence of a “revolving door” at work or immediate promotion. As of the end of 2012, only three of the 15 had been appointed to positions outside of central government.Footnote 55 Only four of the 15 were promoted to ministerial rank during this period, with three promoted immediately (see Table 2). Instead, for most individuals in this group, a central leadership posting would be their final stop before retiring.

Table 2: Core Central SOE Leaders Transferred to Centre Who Attained Ministerial Rank, 2003–2012

Source: Author's database

Conclusion

This paper presents the first comprehensive analysis of the political mobility of a critical elite group – the leaders of China's core central SOEs. It identifies their key demographic attributes between 2003 and 2012: significant advances in professionalization through education, lengthening company and leadership tenures, and stable but weakly institutionalized turnover, with most retiring directly. These findings, summarized in Table 3, raise important questions for further investigation. Did the fact that most of these executives tended to remain within state-owned industry and then retire directly constrain the Party centre's ability to control them? Did their limited political circulation and promotion diminish their incentives to implement SOE reform, thereby contributing to its stagnation under Hu Jintao's leadership? While in theory the cadre management system functions as a key mechanism of Party control, whereby the prospect of promotion aligns officials’ aims with Party goals, disconnect between the two can occur in the state-owned economy just as it does in centre–local relations.

Table 3: Summary of Political Mobility Outcomes by Leader–Year, 2003–2012

Source: Author's database

Note: Summary statistics exclude Liu Benren, who was appointed to a non-core central state-owned company.

This study also demonstrates that a “one-way exit,” rather than a “revolving door,” best characterizes the political mobility of core central state-owned company leaders during the Hu Jintao administration. For most, their executive positions were their last. Those appointed to another political post followed one of three routes, with little overlap: to other core central SOEs; provinces or municipalities; or the centre. Moreover, more than 90 per cent of these appointments were lateral transfers, not promotions. Extant studies have focused on selected individual cases or else have cast a wider empirical net: tracing the career trajectories of state-owned company leaders with positions below the top executive level (for example, deputy general managers); tracking top officials with any former work experience in central state-owned companies, not only executive leadership; or using alternate measures beyond formal administrative rank to assess political mobility, such as Central Committee membership. By systematically analysing all core central SOE leaders between 2003 and 2012, this paper shows that rotation as well as promotion across multiple Party and government bureaucracies was the exception, not the rule.

Finally, this paper underscores the theoretical and empirical importance of lateral transfer – not simply promotion – in understanding China's cadre management system. Serving in multiple leadership positions of the same formal administrative rank, particularly for vice-ministerial ranked officials, is both common and crucial for potential promotion. Researchers should not assume that types and motivations of lateral transfers are homogenous, or that their frequency is constant. For example, the Xi Jinping 习近平 administration's increase in appointments of top executives from one core central state-owned company directly to another suggests that lateral transfers may be even more critical to understanding China's politics and economy in the future.Footnote 56 If scholarship on Chinese officials’ political advancement continues to focus on promotion as the sole political mobility outcome worthy of study, it will fail to identify such vital developments and risk giving a partial and potentially misleading portrayal of the cadre management system itself.

Future studies on Chinese SOE leaders’ political mobility could examine four areas. First, expanding research beyond top executives in the core central state-owned companies will better illuminate the personnel ties and evolving relationship between the Party-state and SOEs at both central and local levels. Second, further research should assess the effect of state-owned company leaders’ transfers on policy implementation and firm performance. Scholars have examined the impact of cadre rotation on policy diffusion and implementation, for example its effect on environmental policy implementation at the local level.Footnote 57 Do state-owned company leaders credited with success in a particular policy area better implement those policies where they are next appointed? Does the posting of high-performing executives to struggling firms or localities actually produce demonstrable gains? Third, when more data about central state-owned companies’ performance are available, statistical studies will be essential to assess the factors that impact their leaders’ subsequent appointments, including the likelihood of different types of lateral transfer.Footnote 58 Finally, network analysis would enable closer examination of the ties among individual SOE leaders and with their potential patrons and how these relationships might influence observed career trajectories. More broadly, it offers an alternative lens through which to examine the shifting balance of power between state-owned companies and other Party and government bureaucracies. These are only some of the important issues that future research on the political mobility of China's SOE leaders could address.

Acknowledgement

I thank Dominic DeSapio, Manfred Elfstrom, Nis Grünberg, Franziska B. Keller, Chien-wen Kou, Samantha A. Vortherms, Jeremy Wallace and Li-An Zhou for their comments on earlier versions of this paper. Support for this research from the Cornell University East Asia Program, the Jeffrey S. Lehman Fund for Scholarly Exchange with China, and the Chinese Scholarship Council is gratefully acknowledged.

Biographical note

Wendy Leutert is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania's Center for the Study of Contemporary China.