Since 2010, Taiwan has experienced a wave of protests against farmland expropriations. The first protest took place on 17 July 2010 after the government destroyed farmland in Dapu 大埔, Miaoli 苗栗 county, to make way for the construction of a new science industrial park. Since that initial action, protestors have banded together with civil society organizations to stage numerous local demonstrations and three nationwide mass actions to protest against land expropriation and to advocate for reform of the relevant laws.

This study focuses on Waiwuli, a village located on the rural–urban fringes and the centre of recent anti-farmland expropriation actions.Footnote 1 A former agricultural community located in the south-west corner of Zhudong 竹東 township in Hsinchu 新竹 county, Waiwuli is now part of the growing Hsinchu metropolis and has been coming under increasing pressure from the expansion of the world-famous Hsinchu Science Industrial Park (HSIP). Waiwuli was demarcated as part of the HSIP development in the late 1970s. While the government has never acquired and re-zoned the land, the community has experienced a significant population increase as the HSIP has grown over the decades.Footnote 2

The recent round of land seizure threats began in the early 2000s. Protests have intensified since the mid-2000s when the government declared its intention to launch a new urban plan in the name of high-tech industry development in Waiwuli. Many influential activists involved in national-scale mobilizations have come from this area, and local protestors have claimed proudly that their comrades’ mobilization capabilities and resolution to fight against farmland expropriation are the strongest among the movement's participants. It is possible that the story behind this specific community can shed light on our understanding of Taiwan's recent anti-farmland expropriation protest movement.

The analysis in this article focuses on the local causes of protest. Existing studies all identify the recent rural resistance against farmland expropriation for high-tech development in Taiwan as a peasant movement – because the local activists are peasants.Footnote 3 Environmental activists and agrarian advocacy groups, who oppose the environmental damage caused by high-tech industry development, the emergence of agri-businesses and free trade policies under globalization, have attempted to draw a connection between this so-called peasant uprising and transnational peasant movements such as the Via Campesina and its discourses regarding small-scale family faming. The conservation of family farms and the building of alliances with peasant households have indeed been fundamental to the campaign. Scholars relate the movement to the discussion of “new peasantries” or “re-peasantization”Footnote 4 and the “new agrarian question,”Footnote 5 all of which question the linear trajectory of de-peasantization and highlight the politics of the “peasant way” as a possible alternative to contest the conventional notion of developmentalism.

The linking of the local protests in Taiwan to a transnational peasant movement and the emphases on “re-peasantization” and the “new agrarian question” thesis did not occur until environmental activists and agrarian advocacy groups began to get involved in the protests. The original factors triggering local activists to mobilize have not been explored in the literature so far, aside from the seemingly obvious one concerning their peasant status.

Peasants have not always acted to preserve their agrarian land. For example, Partha Chatterjee observes that in India, owing to “the rapid growth of cities and industrial regions,” peasants often make “a voluntary choice, shaped by the perception of new opportunities and new desires” to shift to non-agricultural occupations, rather than departing reluctantly and/or by force.Footnote 6 Derek Hall also finds that peasants in South-East Asia have themselves called for their farmland to be re-zoned as non-agricultural to facilitate its sale and have taken action to destroy improvements on their own land to justify its conversion.Footnote 7

As the ecological and economic spaces that were once on the urban fringes become “mega-urban” regions, defining the residents of those spaces as peasants might not be reasonable, even if they are still farming and seeking to keep their land for farming purposes. In his study of western Nonthaburi, Thailand, Marc Askew shows that farming households actively participate in the country's economic development in areas such as industrial development and housing. Askew calls these households agriculturalists, because while agriculture is still actively practised, these farmers have to diversify their use of the land in order to generate more income. Moreover, the owners and users of farmland view it as an economic resource, the disposal of which is determined by strategies taken to support the livelihood of the household and reproduction.Footnote 8

The recent protest movement against farmland expropriation in Taiwan reveals a change from the previous norm. Until recently, agriculturalists on the fringes of Taiwan's major cities were, similar to Askew's observation, supportive of land expropriation policies. Prior to the mid-1980s, agriculturalists felt compelled to defend their property when faced with farmland expropriation – despite the high costs of participating in social protests owing to the authoritarian rule of the Kuomintang – because the government was paying less than the market price for expropriated farmland.Footnote 9 This situation changed, however, after the government implemented a new compensation scheme in 1986 that offered parcels of land in residential or business zones in exchange for expropriated farmland.Footnote 10 As the parcels of land offered as compensation generally appreciated in value over time, the land expropriation policy gained in popularity.Footnote 11 In other words, some farming households in Taiwan saw farmland expropriation as a chance to gain better economic rewards, rather than as a threat, and actively participated in this process. For example, Li Na Chung shows that from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s when the Second Science Industrial Park (SSIP) was designed and built, agriculturists welcomed the new high-tech industrial park and supported the land expropriation policy.Footnote 12 It is, therefore, difficult to explain the recent protests against farmland expropriation through the lens of peasant mobilization. This paper identifies the most prominent local participants in the recent protests in Taiwan to examine alternative triggers to the mobilization. It also looks at why the resistance of local activists to high-tech development projects diverged from agriculturalists’ earlier acquiescence.

This paper suggests that the daily struggles of ordinary workers in Waiwuli to survive amid rising economic and employment insecurity prompted the protests against farmland expropriation. In line with Askew's observations in Thailand, the community's farmland, situated on the urban fringes, has been at the core of the local households’ economic strategies.Footnote 13 During a period of rapid industrialization, it played a significant role in “accumulation without dispossession.”Footnote 14 It continues to function as means of subsistence, social reproduction and economic security for ordinary working families under the intensification of the Taiwanese labour regime's market despotism. The recent farmland expropriation threatens key resources for individual and household coping strategies as working-class employment and entitlement are collapsing or revamping. In this sense, local mobilization against the expropriation of agrarian land is a movement against increasing economic and employment insecurities.

In the context of the escalation of market despotism, increasing economic insecurity and the relocation of firms to China, local activists in Waiwuli began to question the utility of a new industrial science park. Rather than understanding the project as a government-led drive for productive industrialization, local protestors saw it as a real estate development project in which the government and business enterprises were colluding. In other words, they viewed it as a conspiracy, hatched by a private–public partnership, to dispossess them of their private land, spark real estate speculation and benefit from capitalist accumulation.

Polanyi-type Labour Unrest, Livelihood Struggles and Private Ownership of Land

Karl Polanyi's “double-movement” concept is based upon the notion of “fictitious commodities.” He argued that counter movements avert painful social disasters caused by the commodification of “fictitious commodities,” including land and labour, by seeking social protection against the penetration of the law of market.Footnote 15 Although Polanyi focused on the period ranging from the 1830s to the 1940s, his discussion has significant implications for our time because market fundamentalism has resurged since the 1970s.Footnote 16 As Edward Webster and his co-authors observe, market despotism has returned under neoliberal globalization. As the employment conditions change from “full-time, indefinite employment” to “precarious fixed-term, part-time and outsourced employment,” work has intensified and insecurity has grown.Footnote 17

Along with the re-emergence of a self-regulating market that robs people of protective institutions and melds individual human beings into masses, a new wave of social mobilization has begun to counteract this tendency towards commodification, as has been documented by scholars. For instance, in Latin America, as Kenneth M. Roberts shows, varying types of market insecurities have led to increased popular mobilization since the late 1990s when market globalization intensified.Footnote 18 Eduardo Silva contends that neoliberal reforms in Latin America provided the motive for popular mobilization to take place in the 1980s and to gather force and coherence in the 1990s.Footnote 19 Mobilizations against neoliberal globalization can also be found in IndiaFootnote 20 and in Asian labourers’ responses to labour system reform in China, the Philippines, South Korea and Thailand.Footnote 21

Ching Kwan Lee adopts the lens of a Polanyi-type movement to analyse China's rust-belt regions where the collapse and reworking of working-class employment conditions and entitlements have left workers struggling to maintain a livelihood. Despite the fact that China has become the world's powerhouse of global manufacturing and capital accumulation, the dismantling of state-owned enterprises during the process of market reform has unmade its socialist-state working class. Formerly a labour aristocracy with access to employment security, pensions, welfare services and housing under the communist regime, unemployed and retired workers in rust-belt regions where state industries have declined drastically have struggled against the demise of the socialist state's social contract.Footnote 22

In addition to launching collective actions to protest against wage and pension arrears, problems with the maintenance of utilities and public service provisions in working-class neighbourhoods, and issues related to the bankruptcy of state-owned enterprises such as compensation and severance packages, former socialist-state workers have to resort to individual and household coping strategies to maintain a livelihood. Such strategies include relying on their housing, which was previously distributed to them by state-owned enterprises and then became privately owned in the process of market reform, to accommodate unemployed family members or to generate additional income.

Private property ownership plays an even stronger role in Taiwan as it has been the source of social wages, unemployment insurance and old age security for the labouring population during rapid industrialization. They kept hold of their land and their household incomes relied on both farming and wages, a phenomenon described by Gillian Hart as “accumulation without dispossession.”Footnote 23 Hill Gates demonstrates that members of peasant households in Taiwan worked self-exploitatively to support the industrial workforce. Agricultural productivity increased, not only owing to the introduction of new technologies but also because of the rise in the number of working days devoted to agriculture. In addition, when factories shut down, or workers were laid off, young people could be sent back to the farms and be supported by their large and frugal households.Footnote 24 In other words, agrarian land and farming activities not only provided a supplemental income but also an economic fall back when family members lost factory jobs.

Today, workers, including those in the high-tech sector, continue to rely on their private ownership of land as a safety net. Although Taiwan has never had a socialist social contract and the Taiwanese labour regime has been known to expose workers directly to market risk,Footnote 25 the progress of the high-tech sector seemed to constitute a developmental social compact or promise for its workers’ families, because this sector offered stable employment with higher incomes. However, developmental promises have broken down and the land's role as a means for social reproduction has become even more significant in an environment of increasing casualization of employment and ordinary workers’ growing sense of economic insecurity.Footnote 26

Building on Polanyi's double-movement theory and Lee's analysis of workers’ livelihood struggles under market reform, this paper examines the link between the local origins of the protests against farmland expropriation for high-tech development projects and the trend towards the commodification of labour. This paper shows that rather than expecting exchange value from land and believing in developmental promises, families are fighting to keep farmland as a resource that will continue to provide economic security for the household and for the next generation.

Research Design and Data Sources

This paper is based on a case study of the protest participants living in Waiwuli. This community was chosen through a puzzle-driven case selection. Zhudong township and Waiwuli are major beneficiaries of the employment opportunities created by the HSIP.Footnote 27 The fact that many small agriculturalists, as the case of the SSIP shows, supported farmland expropriation also adds to the interest of the case, as the reversal constitutes an unlikely or deviant case, according to Rebecca Jean Emigh's definition.Footnote 28 Such puzzles are valuable ways of examining extant theories.Footnote 29 Analysing this puzzle-driven case should enrich our understanding of Taiwan's anti-farmland seizure protests and double movements in capitalist development.

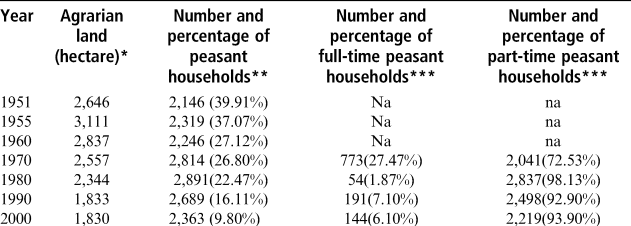

Examining whether the movement deserves to be called a “peasant” movement requires interrogating the term and reviewing the local agrarian changes in Zhudong township, including in Waiwuli. To begin with, “peasant” is a highly problematic category.Footnote 30 The distinction between peasants and other categories “is a particularly acute tension … between the concepts and the reality.”Footnote 31 Taiwanese official statistics essentially follow Alexander V. Chayanov's classical definition, which is based on the use of a familial workforce on family farms.Footnote 32 The official Taiwanese definition of a “peasant household” is a household that farms at least 0.05 hectares of land and hires less than five employees.Footnote 33 Table 1 lists the data based on this definition and shows that the focus area of this study has experienced de-peasantization. While peasant households accounted for 39.91 per cent of total households in 1951 and agrarian land reached its peak in 1955, they both declined rapidly afterwards. Moreover, demographic data show that while the peasantry was the largest segment of the labour force at the beginning of the 1970s, it was overtaken by workers in the manufacturing and service sectors by 1981.Footnote 34

Table 1: De-peasantization in Zhudong Township

Sources:

*Wang and Chen Reference Wang and Chen2007, 69–71, Table 2–1; ** Lu and Wang Reference Lu and Wang2011, 23–23, Table 1–14; *** Wang and Chen Reference Wang and Chen2007, 108, Table 2–238.

In the local language, however, “peasant” (nongmin 农民) has a complicated meaning. Although people growing up in small agriculturalist households and in rural areas may call themselves “peasants,” the term usually refers to people who actually make their living from farming, including small agriculturalists who generate some of their incomes from farming activities. It is exactly according to the latter meaning that local real estate agents and informants other than protestors described peasants as a minority portion of the current landowners in Waiwuli. Households that failed to generate sufficient income from farming had to sell their land as a last resort after real estate speculators looked to invest in expropriated land following the recent development project proposal to expand the HSIP.Footnote 35 Only those households with a relatively stable economic situation (mainly agriculturalist households with family members working in non-farming sectors) were able to hold on to their land.Footnote 36

The study sample reflects the de-peasantization of Waiwuli. Among 15 agriculturalists interviewed by social movement activists in 2009, only three earned a living from farming.Footnote 37 Among the 15 households I spoke with when conducting field research, only one of them was a full-time agriculturalist household, and only three of them earned a living primarily from farming. Most of the other households owning farmland derived their incomes principally from non-farm jobs, including eight households with family members who used to or currently worked for the HSIP firms. The farming workforce generally consisted of family members who were either retired or laid off. Alternatively, households rented out their farmland, let it go fallow or turned it into a “hobby farm.”Footnote 38

This study relies on multiple data sources. First, fieldwork was conducted between late October 2011 and June 2012 and included mostly informal conversations as well as several in-depth interviews with local activists participating in the social protest movement against the government's expropriation of farmland for high-tech development.Footnote 39 This part of the fieldwork aims at exploring the local origins of the activists’ mobilization, as well as uncovering their understanding of and experience in high-tech development projects and farmland expropriation. Moreover, in order to understand the recent changes in high-tech sector employment, this fieldwork includes interviews with members of the human resource departments of high-tech firms. Along with fieldwork, this study analyses official statistics. Additionally, secondary data, including newspapers and published or unpublished materials documented by activists and graduate students, provide valuable information for this study.

Growing Economic and Employment Precarity

It was a cold and windy evening after the 2012 Lunar New Year when I visited Sister Chang's family. Sister Chang was dedicated to fighting the farmland expropriation, and she invited many neighbours who also had participated in the protests to join our conversation. When I asked for their thoughts about the promises offered by the development to expand the HSIP, all expressed scepticism. Mr Cheng said that one of his sons worked as an operator in Company A. Although he worked very hard, the pay was low and job insecurity was high. Sister Chang's husband, Mr Huang, added that Company A had already laid off workers in 2012. As a senior worker for a customs agent whose business depended significantly on the prosperity of HSIP firms, Mr Huang had a clear idea of their financial situation. Moreover, his wife, Sister Chang, was laid off in 2003 after working in the HSIP for 13 years. His neighbour, Sister Cheng, was forced to retire in the same year after working in the HSIP for 23 years. Sister Cheng recalled the day she lost her job: “a member of the human resources department unexpectedly informed me that I was on the retiree list and then ordered me to immediately leave the company under the escort of security guards.”Footnote 40

It has been argued that the recent emergence of welfare programmes that integrate unemployment benefits with job-skills training in Taiwan is a step towards providing more inclusive social protection to labourers; however, the opposite trend has not been considered.Footnote 41 As the country pursues its “Silicon Island” dream, workers in the high-tech sector are experiencing a decline in stable employment and benefits. The Taiwanese labour regime has in the past exposed workers directly to market risk.Footnote 42 But, employment in the high-tech sector was considered to be an exception as Taiwan's high-tech sector offered profit-sharing schemes, linking the profitability of companies to their employees’ incomes.Footnote 43 The relatively high incomes these schemes created and the secure employment offered during the high-tech boom of the 1990s made employment in this sector highly desirable, seemingly constituting a developmental social contract – stable growth in the high-tech industry guaranteeing good jobs and incomes. Starting in the early 2000s, however, the degradation of work in this sector was underway to such an extent that a business magazine termed workers in the sector “the high-tech working poor.”Footnote 44

Two significant changes regarding industrial relations in the high-tech sector accelerated the realization of economic and employment insecurities. The first change, as documented by Chien-Ju Lin in her study of the SSIP, is the casualization of employment in the HSIP.Footnote 45 A contract engineer working in a large high-tech factory reported that all new employees in his company were contract workers.Footnote 46 My interviews with human resources staff revealed that following on from the move towards the casualization of employment in the SSIP in 2002, firms in the HSIP and in other northern Taiwan areas had begun to collaborate with temporary work agencies which were initially used to recruit temporary contract workers for firms in the SSIP. The firms now hire only through these agencies, and only offer permanent positions to contract workers who perform well.Footnote 47 Mr Cheng's son reported that his company, which was located in the HSIP, had replaced permanent workers with contract workers.Footnote 48 Moreover, according to the Labour Party's executive general, many enterprises have set up small companies to operate as contractors to their parent companies and have transferred workers to those contractors. Although still working in the same factory and performing exactly the same tasks, these workers are now employed on a contract rather than permanent basis.Footnote 49

Harsh working conditions that violate labour laws have accompanied the casualization of labour. Reports by the Control Yuan and the Council of Labour Affairs on temporary contract workers in the high-tech sector reveal examples such as illegal overtime shifts and payments, seven-day working weeks, withheld wages and even the use of child labour.Footnote 50 The health hazards caused by increasing workloads, labour flexibility and the casualization of labour have attracted public concern and research interest.Footnote 51

The second change to industrial relations in the high-tech sector is the upsurge in companies’ use of “unpaid leave.” In Taiwan, unpaid leave practices mean that employers actively and unilaterally insist that employees reduce their working hours in line with the company's financial health. Furthermore, workers’ wages are tied to the “no work, no pay” principle. Although in earlier times there were instances when individual enterprises occasionally forced employees to take unpaid leave or imposed temporary wage cuts of up to 50 per cent, such practices have increased massively since 2008.Footnote 52 These labour practices violate labour laws. According to the Hsinchu Labour Investigation Team, enterprises often unilaterally impose unpaid leave on employees without their consent, or pressure them into taking it, and do not make the requisite monthly payments.Footnote 53 Lin Chien-Ju also reports similar treatment of workers in the high-tech sector.Footnote 54 During my conversations with local protesters, many expressed concern that the scale and impact of unpaid leave could increase owing to the recession triggered by the unfolding European debt crisis.Footnote 55

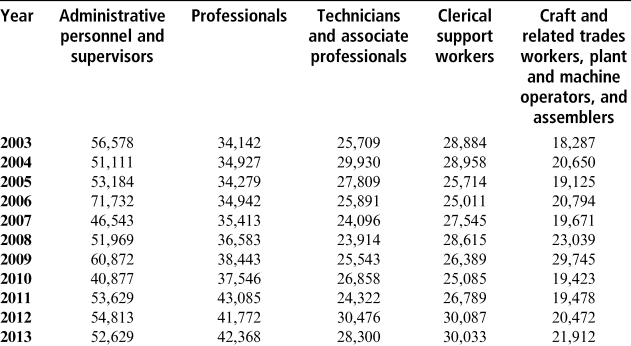

Economic insecurity has increased significantly for Taiwanese workers in general and high-tech workers in particular. Although the average number of working hours per month increased for Taiwanese workers between December 2007 and December 2009, their share of GDP declined.Footnote 56 Table 2 presents the monthly basic wage offered by HSIP firms for vacant posts between 2003 and 2013. It illustrates that ordinary workers’ wages remained low. This was especially true for craft and related trades workers, plant and machine operators, and assemblers. For the most part, companies’ hiring wages hovered at around NT$20,000 (US$630) per month. According to the government, in 2011 the monthly minimum living expenses per person in the Hsinchu area amounted to NT$10,244.Footnote 57 The low wages offered by the HSIP firms mean that single-income families whose breadwinners were ordinary workers working full time in the HSIP would have fallen below the poverty line if they did not have access to other sources of revenue.

Table 2: Monthly Regular Wages Offered by HSIP Firms (NT$)

Sources:

Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan. 2003–2013. “Shiye renli guyong zhuangkuang diaocha” (Job vacancy and employment status survey).

Researchers have also noted the emergence of a new class of young, working poor who are not necessarily less skilled or less educated.Footnote 58 Compared to the rest of the workforce, workers aged 15 to 29 years old are more likely to experience unemployment, underemployment and long-term unemployment (over 27 weeks). The percentage of young workers embarking on part-time jobs grew consistently between 1991 and 2005. Moreover, the young, working poor have few career prospects. They are more likely to experience persistent unstable employment between graduating from school and getting their first full-time job, or between two permanent jobs. In fact, they may remain in precarious work.Footnote 59 The casualization of work and insecure economic conditions not only make young workers feel financially vulnerable and doubt their career prospects but they also raise their parents’ concerns about their future survival and welfare.

Although increasing fears about employment and economic security have spurred workers to organize themselves and to launch collective actions, most workers still rely primarily on their own individual strategies to cope with rising market despotism and economic difficulties.Footnote 60 Landowners view farmland as an economic resource, the disposal of which is determined by whatever strategy the household adopts to maintain its livelihood. In this context, local protestors fought to retain their land, even though the government improved its compensation scheme for farmland expropriation. The compensation scheme offered from the late 1980s to 1990s included a cash payment and a provision for accommodation. The government unilaterally set the amount offered in cash, which was considerably lower than the market price. Furthermore, the provision of accommodation disadvantaged owners of larger pieces of land since the formula was capped at 1.9836 hectares; thus, regardless of how much land they had, households were only given a housing unit of 991.71 square metres.Footnote 61 The cap has since been abolished. Landowners can now exchange all their farmland for land located within the planned commercial or residential zones and avoid any cash compensation below the market price.Footnote 62 However, agriculturalist households are reluctant to give up the farmland that their families acquired through Taiwan's post-war redistributive land reform because that land forms part of those households’ strategies to combat increasingly unstable employment conditions and economic insecurity.

Mr Lin's story demonstrates that unemployed workers are not the only ones who look to the land to generate income after losing stable employment. Mr Lin was a young retiree in his mid-40s whose children were still in school or had just begun their working careers. Like many others in his age group in Waiwuli, he had become an irregular worker. For example, he earned a piece-rate wage based on the number of solar panels he installed. On the evening that I visited him, he was discussing the possibility of training to be a part-time construction worker with one of his friends. A few years before his retirement, Mr Lin had begun to grow rice on his 0.5 hectares of farmland. Since leaving the factory, he had also found some temporary work as a farmhand for an older farmer. Mr Lin used the income he gained from farming to support his mother.Footnote 63 Some members of Mr Lin's cohort had managed to find jobs in the HSIP but in much lower positions. After being laid off in 2005 and again in 2008, Mrs Yu had found a lower-paid job in another HSIP factory.Footnote 64 Mrs Lin had found a job in another HSIP factory after being laid off by the corporation she had worked at for 16 years. Her new employer treated her like a novice in spite of her years of experience. She also had to accept worse working conditions, such as lower pay, longer working hours and unstable employment.Footnote 65

Working on family farms offers an alternative to working in the factories. After an HSIP firm laid her off in 2003, Sister Chang initially intended to find a job in another high-tech factory, but ultimately decided not to:

I worked as a motherboard cleaner. Because of working in an environment filled with toxic materials, my health was getting worse. When interviewed by another factory, I had a chance to see its assembly line. I felt that the degree of protection it offered workers was less than that offered by my previous company. Moreover, the working conditions were not good. I thus decided not to go.Footnote 66

Instead, Sister Chang turned her hand to farming. She also asked her two sons, both college graduates, to help on the family farm instead of seeking high-tech work. She did not want them to suffer the health hazards and bad working conditions of high-tech production and hoped working conditions would eventually improve. Thus, while her husband, who worked as a customs agent, remained the primary breadwinner, Sister Chang and her sons generated a supplementary income from working the family farm. In Waiwuli, cultivation has intensified as the economic role of agrarian land has increased in recent years.Footnote 67

Sister Cheng and Sister Tseng had also begun working on their family farms after leaving factories in the HSIP. Sister Cheng's husband was a government employee and so her family had relative financial stability. Nevertheless, while her youngest son worked as an operator in the HSIP, her oldest son, in his early 30s, was still looking for a job. After being forced to take early retirement in 2003, Sister Cheng became a helper on the family farm in order to bring in supplementary income. The farm increased production and so her oldest son also began working there while he continued searching for a job.Footnote 68 Sister Tseng, whose husband was still working in the HSIP, had been helping her father-in-law farm his cash crop of sweet potatoes since leaving the HSIP. Her family also grew some vegetables and rice for household consumption.Footnote 69

Agricultural production for household consumption has grown in Waiwuli in recent years. Mr Lin showed me around the farms near his house on the day he introduced me to the old farmer who hired him as a temporary helper. According to Mr Lin, many farms had been left to lie fallow a few years ago but recent economic conditions had led local residents to resume farming and growing vegetables for their own consumption in order to cut living expenses. Sister Tseng informed me that the surplus harvest could also be used as gifts, which was another way to save money during an economic downturn.Footnote 70

Agrarian land also has accommodated workers who have had been hit hard by unpaid leave. Mr Tseng's son, in his mid-30s, came home to help grow tomatoes while taking unpaid leave in 2009. “It is lucky that our land is still there,” he said. The family farm could temporarily absorb his labour surplus.Footnote 71 It was in this context that local protestors frequently pointed to the growing significance of farmland as a means of subsistence as many local people are facing increased economic insecurity owing to the downgrading in employment and conditions in high-tech sector companies.

Even more than the boost to incomes and savings on food expenses that farmland provides, local protestors are concerned about the futures of the next generation. For example, Mr Lin said that while his parents could earn enough money to buy land and a house by working hard, economic opportunities appeared to be very limited for his children's generation.Footnote 72 Mrs Yu said:

People of my generation usually have some savings and a higher pension payment. We do not expect our children to take care of us when we are getting old. Thus, we keep working until jobs are gone. That is why we can live with a low-wage job now. For the younger generation, though, they cannot expect to have stable employment since high-tech production changes too fast. Moreover, they cannot save money, because of low wages.Footnote 73

Sister Cheng informed me that:

My children's generation enjoyed a good material life when growing up. They had good food and good clothes. Nevertheless, the situation is very difficult for them now when they start working. They can barely survive. They can hardly have enough money to get married. I do not even expect that they can afford to buy their own houses.Footnote 74

Without the financial help of parents, it is difficult for the younger generation to survive financially. Sister Cheng's oldest son was unable to find work and her youngest son had been working as an operator for four years but still only earned NT$26,000 (US$815) per month. Sister Cheng, Mrs Yu and many others resisted farmland expropriation first and foremost because of their concerns about their children's economic security. According to these protestors, as long as their children were willing to live off the land, they would not starve and could have a place to stay, even if employment conditions worsened. A key local protest organizer told me, “at least I can give [my children] a hoe. If they still suffer with starvation, it is not my problem.”Footnote 75

It is clear that rather than a crisis over the immediate survival of agriculturalist households, the main concern behind the local mobilization against farmland expropriation is the survival of the next generation of the labouring population – many of them the young and working poor. Moreover, many are feeling financially insecure, to the extent that even some young local protestors who have decent jobs also worry about the economic difficulties their children will face in the future. Take Mr Fu and Mrs Chu's daughter-in-law as two examples. In his early 40s, Mr Fu worked as an engineer in the Industrial Technology Research Institute. He was determined to leave his 0.6 hectares of farmland, which he was renting out when I visited him, to his children.Footnote 76 Mrs Chu's daughter-in-law, in her mid-30s, was a government employee. Her family was also determined to keep its 0.3 hectares of a hobby farm for future generations.Footnote 77

A further point worth mentioning is that for local protestors, farming is seen as an interim measure towards land preservation since they do not necessarily expect their children to live solely off farming. In fact, the land use regulations regarding agrarian land in Taiwan have been relaxed since the 1990s, because the country gave up its food self-sufficiency policy.Footnote 78 As a result, farmland has become an even more valuable resource, because of its potential to satisfy diversified needs. For example, if children are unable to purchase their own home, then they could at least live on the family farm, however humbling this might be. It is also possible for children to use farmland to start a small business when under- or unemployed. In other words, preserving farmland does not mean that land use will never change. Instead, farming becomes a temporary fix – a kind of land use that members of the next generation could adapt according to their economic needs. Agrarian land is a valuable resource in the context of employment and economic insecurity, one that small agriculturalists are unwilling to relinquish now that the high-tech development promise has failed to deliver.

The Broken Promise Regarding High-tech Development

The degradation of employment terms and conditions has led many local protestors to doubt the high-tech development promise. They do not believe the claim that the expansion of the HSIP could resolve the younger generations’ economic difficulties and insecurity. Mr Zhang offered the example of his daughter, a college degree holder, to illustrate how HSIP firms treat their workers. His daughter had worked as an operator in the HSIP but had only been able to get irregular work after she was laid off in 2009.Footnote 79 Mr Lin and Mr Peng informed me that the expansion of the HSIP and the arrival of new factories would not guarantee their children jobs because they would have to compete for the jobs with people from other places. And, even if they managed to get work, there was no expectation of secure employment.Footnote 80

The relocation of Taiwanese high-tech manufacturing firms to China has also led many local protesters to suggest that the expansion of the HSIP would not attract more employers in any case. Both scholarship and a government document have revealed that heavy subsidies and tax cuts offered by the Taiwanese government have not deterred enterprises from relocating their manufacturing plants to China where labour costs are lower. Whereas every NT$10 billion (US$330 million) the government invests in the traditional industrial sector creates 16 jobs, comparable investment in the high-tech sector produces only 6.4 jobs. The government's spending on encouraging high-tech production has produced very little return.Footnote 81 Thus, there is a very real basis to local protestors’ concerns that factories built on their expropriated land might stand empty.

Sister Cheng's oldest son informed me: “if firms are willing to move in, it is fine. That can create jobs. However, given that most firms now move to China, is there any firm that really wants to move in?”Footnote 82 And, Mr Fu told me:

I have worked in the Industrial Technology Research Institute for a long time, and people there are very conscious of the relocation of firms during this decade. Ten years ago, when my colleagues, many of them engineers and technicians, were sought after by headhunters, they went to work at factories in the HSIP. Who is being headhunted by HSIP firms now? Most of them go to work for firms in China. How is it possible that enterprises will invest here under this kind of situation?Footnote 83

Mr Fan, an engineer working in the HSIP, was among many others making the same point.Footnote 84 He pointed out that some plants in the HSIP had already become vacant.Footnote 85 Given these realities, protestors suspect that the real rationale for farmland expropriation is land speculation.

Local protestors’ current doubts about the high-tech development promise contrast sharply to the reception farmland owners gave to land expropriation during the late 1990s when the Second Science Industrial Park Special District (SSIP Special District) was being established. Farmland owners in the SSIP Special District believed that the high-tech development project could create jobs, benefit local economic growth and boost land prices.Footnote 86 Agriculturalists in Waiwuli have no such faith.

Michael Levien's description of the politics of dispossession is applicable to the situation in Waiwuli.Footnote 87 According to him, dispossessing land “involves the use of routine and highly visible extra-economic coercion,” which cannot be obscured in land seizures, but instead must be “explicitly justified” (italics in original). This means that the government has to explain publicly why it is appropriate to violate citizens’ property rights. These justifications include material promises made by the government (jobs and compensation) and an ideology that “takes the form of explicit appeals to the ‘public’ or ‘national’ interests that are served by this coercive redistribution of property.”Footnote 88 As Levien points out, however, the persuasiveness of these justifications varies according to particular times and spaces. For example, in India, the government-led projects of productive industrialization through land dispossession had significant legitimacy in the Nehruvian era. In the neoliberal era, when the government has “become a mere land broker for increasingly real-estate driven private capital,” those justifications are much less persuasive.Footnote 89

Levien's framework sheds light on the dichotomy between different local responses to the land expropriation for high-tech development projects from farmland owners in the SSIP Special District and Waiwuli. The construction of the SSIP Special District began when the casualization of labour in SSIP had just started.Footnote 90 People did not expect to see an increase in precarious employment and economic insecurity but instead expected more prosperity and the fulfilment of the project's material promises. Moreover, if the high-tech production boom of the mid-1990s and 2000 could be reproduced in the SSIP, it would bring many public benefits. Owing to these considerations, farmland owners were willing to sacrifice their property rights and means of social reproduction in exchange for economic growth, new employment opportunities and a better material life. They also hoped that local economic growth would boost land prices.

These promises failed to materialize and hopes diminished with the emergence of unpaid leave and economic difficulties.Footnote 91 As a result, farmland owners in Waiwuli were sceptical of the proposed benefits offered by the 2004 development project to expand the HSIP. As the trend towards precarious employment and economic in security became clearer, local protestors were unconvinced by the development project's promises, although the government continually emphasized that land expropriation was a necessary measure to satisfy the need for high-tech development.Footnote 92 The protestors did not believe that this development project would bring decent jobs and new employment opportunities. Indeed, the land seizures were seen not only as an unnecessary policy but also as a conspiracy to trigger real estate speculation. Local protestors’ petition documents and my fieldwork reveal claims challenging the necessity of expanding the HSIP as well as the legitimacy of real estate development driven by the government in collaboration with enterprises. Local protestors characterized this public–private partnership as “a corruptive conspiracy between officials and businessmen” (guan shang gou jie 官商勾結).

Conclusion

The dynamics and protagonists in the above ethnographical work present a very different picture from the popular view of the protest. Taiwan's recent anti-farmland expropriation protest movement has been linked to the transnational peasant movement, and arguments have been made supporting the concept of “the new peasantries,” “repeasantization” and “new agrarian question” by agrarian advocacy NGOs, social movement activists and intellectuals. However, the movement stems from the mobilization of the labouring populations to protect their land. This is especially true for local communities on the “urban fringes” or in “mega-urban” regions that previously enjoyed stable employment and the economic fruits of high-tech development. Local activists in the area under study, Waiwuli, have been particularly determined to resist the recent developmental project and farmland expropriation.

Waiwuli resembles western Nonthaburi, Thailand, where Askew's study is set. He found that agriculturalists there treat their farmland as an economic back up for the household and actively modify land use according to the changing economic environment, even when still farming.Footnote 93 Households are holding on to their land for farming even when their family members work for high-tech firms and in spite of their dependence on high-tech sector jobs for income. Against a backdrop of increasing market despotism, economic insecurity and firms’ relocation to China, private farmland ownership in Taiwan has continually functioned as means of subsistence and social reproduction and as a source of economic security. Local protestors are especially concerned about preserving the farmland for the next generation. This does not necessarily mean that they expect the younger generation to earn their livelihoods from farming; the land could be used for housing or other economic activities in the future, as needed.

Just as workers in China's rust-belt regions relied on private house ownership as a resource for individual/familial coping strategies when faced with the collapse and revamping of working-class employment and entitlement, ordinary Taiwanese workers are now turning to their privately owned farmland in response to the demise of the high-tech developmental social contract. The government's promises and its “explicitly justified” reasoning for pursuing the “Silicon Island” dream through farmland expropriation hardly have any legitimacy now. These changes have led to the local residents’ doubts about the development project, which is attempting to expand the HSIP by taking away their resources for the social reproduction of labour and economic security. In this sense, the local mobilization aimed at protecting agrarian land forms part of the labouring population's livelihood struggles, a Polanyi-type movement against increasing economic and employment insecurities.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan for providing funding to support this study. The author would also like to thank the reviewers for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical note

You-Lin TSAI is assistant professor in the department of sociology at National Dong Hwa University, Hualien, Taiwan, ROC.