Owing to a combination of birth control policies, urbanization, economic growth and the increases in educational attainment that began in the 1980s, most urban Chinese young adults now have no siblings.Footnote 1 In 2016, however, China ended the one-child policy that had limited most urban families to one child since 1979 and started permitting all couples to have a second child, with the aim of reducing the aging population, alleviating labour shortages and correcting sex imbalances exacerbated by previous birth control policies.Footnote 2 Now that they are allowed to have a second child, the question of how, why and to what extent Chinese couples are willing to have a second child will have important implications for China's future population size and structure.

China's one-child policy not only contributed to the fertility decline of the 1980sFootnote 3 but also led to increased investment in each singleton child born under that policy, which in turn spurred a rapid inflation of the costs of childrearing and education.Footnote 4 Recent studies suggest that these costs have become major considerations for Chinese young adults born under the one-child policy as they decide on how many children they themselves want.Footnote 5 No previous studies, however, have examined how these young adults feel about their experiences of siblinghood, or lack thereof, and how these feelings impact their own fertility preferences. This article helps to fill this gap in the literature by examining how Chinese young adults’ fertility preferences are influenced by their evaluation of the costs and benefits of having or not having a sibling in their own lives.

Intergenerational Transmission of Fertility: Siblinghood and Fertility Preferences

Studies of how siblings influence an individual's fertility in developed countries have usually demonstrated a positive correlation between one's sibship size and the number of children one has.Footnote 6 Individuals with more siblings tend to prefer and have more children, and those with fewer siblings tend to prefer and have fewer children. The intergenerational transmission of fertility preferences and behaviour has been observed in many countries and historical periods. Using survey data from 46 populations in 28 developed countries, Michael Murphy has documented a robust positive intergenerational fertility correlation across these countries and finds that the association does not appear to weaken over time.Footnote 7 In populations that practise widespread contraception, among whom fertility behaviour is deliberately and efficiently controlled, the level of intergenerational transmission of fertility preferences and behaviour is even higher than in the past, and the magnitude of the association between sibsize and fertility preference is comparable to the magnitude of the effect of education level on fertilityFootnote 8

While some studies in the US, Netherlands and Denmark argue that the intergenerational transmission of fertility behaviour may be owing partly to the genetic heritability of fertility,Footnote 9 studies which find that sibship size influences one's fertility preferences as well as behaviour suggest that socialization plays a large role in the transmission of fertility behaviour.Footnote 10 Laura Bernardi suggests that the family structure children experience during their early formative years will lead them to want to create the same kind of family that they experienced as children.Footnote 11 Fertility preferences may be formed indirectly by the passive internalization of parents’ expressed ideals for family size or more directly as a result of parents’ pressure or support. In addition, the direct experiences of the consequences of parents’ fertility behaviour, such as experiences of siblinghood, may also influence a person's fertility preferences.Footnote 12

The effects of childhood interactions with siblings may attenuate as young people grow older and face the realities of parenthood. Studies in the US and France have found that young people's fertility preferences become more realistic as they enter adulthood and parenthood, leading to the consequent modification of their ideal number of children.Footnote 13 Socio-economic changes, societal fertility transitions, increased individualism, decreased family stability, wider opportunities for labour force participation and diminished religious and parental influences may reduce the likelihood of children displaying the same fertility preferences and behaviour as their parents.Footnote 14 Other studies in the US and Denmark, however, have found robust continuities in fertility behaviour across generations of the same families, despite the big changes these societies experienced over the last half of the 20th century.Footnote 15

Drawing on data from the Norwegian and Swedish series of the Generation and Gender Survey, Felicia Wibe is among the few who have looked specifically at the fertility preferences of singletons.Footnote 16 She has found that singletons are more likely than siblings to want, and have, singletons of their own. In addition, studies examining the determinants of having just one child in France and Australia have found that even after controlling for marital status and women's age at first birth, a parent's own singleton status significantly increases the likelihood of that parent having a singleton.Footnote 17 These findings suggest that the transmission of fertility preferences and behaviour from parents to children has been common among singletons in Western societies.

Singletons may favour having singletons themselves because they know from their own experiences that undivided parental time, money and energy can be allocated to a singleton to maximize that child's well-being and success. Prior research in the UK and China has found a negative association between sibship size and the amount of resources a child receives from the family.Footnote 18 Studies in the US and the UK report that because they did not have to share family resources with siblings, singletons tend to have more educational attainment and self-esteem than their counterparts with siblings.Footnote 19 Drawing on Gary Becker's theory on human capital and family formation,Footnote 20 Wibe argues that singletons who benefit from concentrated family resources in childhood, and consequently more resources in adulthood, may be more likely to have or prefer to have singletons themselves.Footnote 21

But, having no siblings can also be regarded as a disadvantage. In studies conducted in China and the US, wanting to prevent the firstborn from being a singleton was among the most frequently cited reasons for wanting more than one child.Footnote 22 Ann Laybourn explains that in the UK, few parents choose to have only one child, and singletons are widely perceived to be spoiled, lonely and maladjusted.Footnote 23 Similarly, Judith Blake reports that in the US, singletons on average want fewer children than do people with siblings; however, singletons are not more likely to prefer to have singletons, as they are influenced by the negative stereotypes of singletons.Footnote 24 In the US, singletons were often perceived as selfish, spoiled and unsociable.Footnote 25 Toni Falbo and Denise Polit explain that because singletons are deprived of the social experiences that siblinghood offers, they are more often seen as lacking social competence than are those with siblings.Footnote 26 Additionally, singletons are often depicted as anxious, domineering, self-centred and quarrelsome.Footnote 27 In South Korea, singletons score higher in “brattiness” when compared to those with siblings, although singletons’ scores for popularity and sociability are similar to those of siblings.Footnote 28 In the Netherlands, Ruut Veenhoven and Maykel Verkuyten report that singletons are often perceived to be “little eggheads” who perform well in academic subjects but poorly in athletics and social life.Footnote 29

Many studies have examined the idea, widespread in China as well as abroad, that Chinese singletons have grown up as spoiled “little emperors.” The implementation of China's one-child policy led many in China and abroad to fear that the resulting generation of singletons would grow up with more socio-emotional problems than previous generations had.Footnote 30 Studies investigating the actual effects of singleton status in China, however, show mixed results. Using a comparative study of rural and urban Chinese schoolchildren, Shulan Jiao, Guiping Ji and Qicheng Jing together have found that when evaluated by peers, singletons are regarded as less independent thinking, less persistent, less cooperative and more egocentric than children with siblings.Footnote 31 Drawing on data from a similar Chinese sample, however, Falbo and colleagues find that there are no significant differences between singletons and children with siblings with regards to how likely their teachers and mothers are to report that they have undesirable personality traits.Footnote 32 Studies comparing singletons with siblings in China are often confounded by the selection bias built into the implementation of China's birth control policies under which siblings were more likely to be born to rural or ethnic minority parents, who were often allowed to have two children, and to wealthier families, who were more willing and able to pay the fines levied on those who defied the one-child policy.

While many studies in China and worldwide have found that worries about singletons developing undesirable traits motivate parents’ preference for having a second child, little is known about how the subjective experience of being a singleton might affect a singleton's own desire to have a singleton rather than two children. One of the few studies addressing this question was undertaken by Lisen Roberts and Priscilla Blanton, who report on how young American singleton adults evaluate the effects of their singleton status.Footnote 33 Singletons in their study suggested that singleton status offers them a lack of sibling rivalry, an enjoyment of solitary time, an appreciation of being the sole recipient of parents’ resources, and the development of close parental relationships. On the other hand, these singletons also felt that they lack a sibling confidante, experience greater pressure to succeed, have difficulty in social interactions, have more stress relating to caring for aging parents and more emptiness after parental deaths than they imagined they would have if they had a sibling. Overall, though, Roberts and Blanton found that most singletons are accepting of their singleton status since most adult singletons in their study did not feel unhappy about their lack of siblings or wished they had a sibling.

Since 2016, when the Chinese government began to allow all of its citizens to have up to two children, scholars, journalists and policymakers have wondered whether the current generation of Chinese young adults would take advantage of this policy change.Footnote 34 Now that they are legally allowed to have two children, will their fertility preferences resemble those that have led to the two-child family that is common in Europe?Footnote 35 Or have they become so comfortable with the single-child family model that they grew up with that they will prefer to re-create such a norm even in the absence of a government-imposed one-child policy? To help answer such questions, this article examines Chinese young adults’ evaluations of their own experiences as singletons or siblings and how they believe these evaluations are affecting their own fertility preferences. We also examine the perspectives of singletons’ spouses and former classmates with siblings to provide a comparative perspective.

Research Methods

Our data come from a longitudinal study of China's singleton generation started by Vanessa Fong in 1999 when she surveyed 738 singletons while they attended eighth or ninth grade at a middle school in Dalian 大连 in Liaoning province.Footnote 36 She purposively chose the school because its student population was academically, demographically and socio-economically similar to the overall population of Dalian middle school students in 1998–1999.

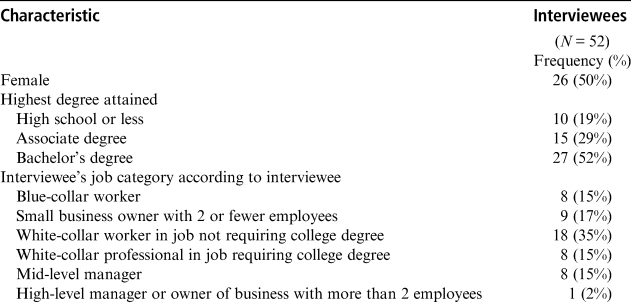

This article draws on interviews with 29 of those respondents and their spouses, which were conducted within the first two years after their first wedding, while they were childless newlyweds (see Table 1 for interviewees’ demographics). These 29 were selected as a socio-economically and demographically representative subsample of our childless newlywed survey respondents.Footnote 37 We focus on childless newlyweds in order to examine how interviewees’ own experiences as singletons or siblings shaped their fertility preferences, before they were influenced by the needs and opinions of a first child.

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of Childless Newlywed Respondents, 2012–2018

Fong interviewed and surveyed all 29 alumni and their spouses in Mandarin Chinese between 2012 and 2018. Six of our 29 newlywed alumni interviewees were married to each other, so our interview subsample includes 26 heterosexual couples (52 interviewees). All interviewees’ names in this article are pseudonyms.

Among our 29 alumni interviewees, only two had siblings, as all but one of the alumni interviewees were born in urban areas, where China's one-child policy applied to almost every family. Among the 23 non-alumni spouses, however, seven had siblings, as some of them were born in rural villages where more families were allowed to have two children.Footnote 38

Wanting Two Children as a Result of Valuing or Missing Siblings

During adulthood, both singletons and siblings valued siblings as people they could talk to, receive support from and share the burden of filial responsibilities with. Most singletons and siblings alike also recalled valuing siblings as companions during childhood (see Table 2). This led most of them to want or consider wanting two children. When they were interviewed as childless newlyweds between 2012 and 2018, our 52 interviewees (who were on average 30 years old) all wanted at least one child, and only 35 per cent wanted one, and only one, child (see Table 3). All interviewees who wanted or considered wanting only one child attributed this desire to fear of not having enough time, money and help with childcare to raise two children well, and not to a belief that it was better to be a singleton than to be a sibling. All interviewees who wanted or considered wanting two children, however, attributed their desire to belief in the social and psychological value of siblinghood.

Table 2: Views on Singleton vs Sibling Status of Childless Newlywed Respondents, 2012–2018

Table 3: Fertility Desire of Childless Newlywed Respondents, 2012–2018

When asked what they considered to be the ideal age and gender for a sibling, most interviewees indicated a preference for a sibling of similar age and the same gender as themselves. Of those who wished for a sibling of the opposite gender, most wished for older sisters, since, as singleton male Shi Yuan said, “an older sister would be especially caring.” For similar reasons, of those who preferred a sibling of a specific age, most preferred an older sibling, both while they were children and now they were adults. Their desire for an older sibling during childhood was based mostly on their desire for someone who could protect them from bullies and serve as an additional source of the kind of care and guidance their parents provided, while not outcompeting them for family resources as a cuter, more helpless younger sibling might. During adulthood, though, they focused on how an older sibling could serve as a mentor who understood the social norms and workplace challenges their generation faced, which were quite different from those their parents had faced as young adults in Maoist China during the 1960s and 1970s.

Siblings as companions and protectors

Singletons who recalled wanting a sibling while they were children believed that a sibling would have alleviated their childhood loneliness. Singleton Yang Xu said he wanted a sibling when he was a boy because “I wanted to have a companion. This way I would be less lonely.” Female singleton Jin Ni said: “I felt that my parents were always busy at work, while I would be by myself at home. There was no one to play with, no one to chat with. It was too lonely.”

Many singletons also believed that a sibling (especially an older one) could have been an additional source of care and protection. Singleton Peng Hao, who wanted a sibling as a child and still wanted one as an adult, said that as a child he wanted to “have an older sister who would be very caring … It's that type of feeling, the feeling of being cared for, being loved, that is pretty nice … The type of care and love between siblings is not exactly the same as what you get from parents.” Singleton male Xu Jun said, “I want to have two [children]. Because of this one-child policy, I am a singleton and am too lonely. I want two so they have a companion.” Singleton female Feng Lan said, “I hope to have two because at the very least they would have a companion. Both my husband and I are singletons, not having a companion was pretty lonely.”

Most siblings’ descriptions of their own experiences of siblinghood were as positive as singletons imagined they might be. Wang Li, who has a sister three years younger, said she appreciated having a sister because “I didn't feel lonely … when I was alone at home, my younger sister provided me with company, I felt that was good. There were also times when I had secrets I could not share with my parents, but I could share them with her … Sometimes, if others bullied me, my younger sister helped me. She protected me.”

Similarly, Wang Li's husband Yi Nong, who has a brother five years older, said that he appreciated having a brother, “because you had someone to help you in fights.” When asked if he felt more or less fortunate than the singletons he grew up with, he enthusiastically replied that he felt more fortunate than them. He also appreciated the positive effect that his brother had on his own growth and character and said that he felt fortunate to have his brother as a role model even though, Yi Nong added, he was unable to continue his education after ninth grade because his parents had already used up their savings by then to pay for his brother's high school education. Yi Nong related his positive experiences of having a brother to his desire to have two children, saying, “If we have time, of course we will want to have two.” Yi Nong's wife, Wang Li, likewise said, “If circumstances allow, I would want to have two, because I feel that nowadays children are very lonely. I have a younger sister and I feel very good about this.”

Pan Hong, who has a sister nine years older, said she wanted to have two children so they could protect each other from loneliness and boredom, just as she and her sister had: “With two children, they can discuss things and talk with each other … one would be too lonely.” Bai Lin, who has a brother 18 months younger, said she wanted two children because “two children wouldn't be lonely, and later on, they can take care of each other and support each other – a sibling can be as close as a mother.”

Lei Lu, who has a sister four years younger, said she wanted two children because “singletons are more selfish and focused on themselves when they try to deal with things.” She wanted her own children to be more caring, like her: “I have a younger sister, so I tend to think more [about others].”

Zhou Ting, who has a sister 12 years older, said that growing up with a sister made her more compassionate than most singletons tend to be:

I feel that, not being a singleton, it may be that I have a better understanding of sharing. If you are alone, your parents might spoil you, everything is yours. You may have a more selfish way of thinking. But, like this [with a sister], you may sometimes be more considerate. For example, if you had something, you would share it with your sister, you would be thinking of her.

Although she acknowledged that she and her older sister occasionally fought as children, Zhou Ting appreciated having developed into a more caring person as a result of having a sibling, and therefore hoped to have two children herself.

Many singletons also believed that singletons might be at disadvantage when it came to developing social skills. As singleton Yang Xu said, “Singletons may grow up lacking communication and social interactions with kids of their own age. Lacking these abilities will more or less impact their future in negative ways.” He wanted two children because he believed that “with two children growing up, they will keep each other company and it is like growing up in a small collective group.” Singleton Lin Jia likewise said she wanted two children because “they may be more able to interact with others of the same age” if they grow up with a sibling. She hoped that “maybe their experiences in such a small collective group will later help them develop a larger collectively oriented mind-set after they start going to school.”

Siblings as mentors and confidants

During adulthood, interviewees’ desire for a sibling's companionship, care and protection persisted, but shifted to how such benefits might matter in adult life. Interviewees imagined that their own children would also need sibling companionship in adulthood.

Singleton Shi Yuan, who recalled having yearned for an older sister during childhood because “sometimes if I had some thoughts, or if there were some things I didn't understand, I could have communicated with her, and just the feeling of being cared and loved would have been very good,” said that he still yearned for an older sister in adulthood, but for more mature reasons:

Sometimes, there are matters, pressures and hardships that cannot be discussed with parents for fear of adding to their worries. Because if the child's career or family is not going well, they will be very worried. But things can be much better if there is communication between siblings, because they have gone through similar things, similar experiences. Some mentalities they should be able to understand. In other words, they wouldn't take these things as seriously as parents would; they wouldn't let it affect their emotional state.

Singleton Qian Rui said that he had no desire for a sibling when he was a child but he yearned for a sibling now that he was an adult:

If I encounter immense pressure or trouble from work, I don't want to bother my parents with these issues. First, my parents may not be able to help; second, it would only make their burden heavier … A sibling would understand everything I have to say about the pressure and stress at work … I would like a sibling, especially an older brother or sister so we can talk about these issues.

Because they were born under the one-child policy at a time when economic reforms ushered in increases in globalization, individualism, competition, job insecurity, income inequalities, economic growth and educational attainment, our interviewees (most of whom had college degrees) felt that their parents (most of whom had no more than a ninth-grade education) could not understand or help with the problems they faced at work or in relationships as well as someone of their own generation, such as a sibling, could. As female singleton Hu Fei said:

Because there is a generation gap between us, they [parents] would not understand. But, if there were someone around my age, either an older or younger sister, as long as our ages were not too far off, one or two years in difference, there would be greater understanding and we would be more emotionally sound.

Pan Hong, who has a sister nine years older who, she said, had been even more important than her parents in helping her to choose her vocational high school major in computer science, confirmed that a sibling could indeed provide unique kinds of help, communication and understanding that a parent could not. When asked about the differences between her experience as a sibling and those of singletons, she responded:

I feel a situation with two children is still better … because when you encounter something or when you want to talk about something, there is still a generation gap between you and your parents … These types of things, you can only discuss with your sister, and having these kinds of heart-to-heart talks is good … If you were by yourself and you didn't want to discuss things with your parents and you could only keep it to yourself and swallow it, you might create psychological pressure and distress.

Many singletons attributed their desire for two children to wanting to prevent their children from feeling as lonely they themselves had felt as children and, indeed, continued to feel as adults. Singleton Qian Rui, who yearned for an older sibling to understand and guide him in times of stress and trouble, believed his children “will also encounter similar situations some day” and would need a sibling to help during these “moments of helplessness.”

Some interviewees feared that if they had only one child, their singleton children would have no one left in the family to connect with once they passed away. Singleton Tang Xin said she wanted two children so that “they can at least have someone to discuss matters with” after she and her husband passed away or were too old to help them with decision making. Singleton Jiang Tao said he wanted two children so that they could provide each other with companionship after he and his wife died: “We'll have to leave something for our children to inherit, and of all the things we could leave them, a kinsperson would be the best.”

Siblings as sharers of filial responsibilities

As they had become adults and realized how difficult it would be to shoulder their filial responsibilities alone, many interviewees were more aware of how siblings might lighten each other's filial responsibilities. Our interviewees had higher incomes and better pension plans and insurance policies than their parents did, and therefore were less likely than their own parents to believe that they would have to depend on their children for financial support in old age. However, they still recognized that it was possible that their plans for relying on savings, pensions, insurance and paid care would be inadequate in their old age. In addition, many of them knew, based on their own experiences of caring for parents and grandparents, that there would be social and emotional aspects of elder care that money could not buy and that only trusted, loving adult children could provide. They recognized how difficult it would be for their own mostly singleton generation to find the time, energy and emotional strength to provide companionship, nursing care and assistance with everyday tasks to parents and grandparents facing increasing levels of loneliness, disability, illness and sometimes cognitive decline, and feared that it would be even more difficult for their own future children (who would be part of the first generation in which most urbanites will lack aunts, uncles, cousins, nephews and nieces) to provide such elder care without siblings. Some therefore said they hoped to have two children so that these offspring could eventually share the burdens of elder care with each other.

Female singleton Ji Ping said: “In the future, when they have to care for the elderly, one child would be too few, and would be too tired. Two children would be better.” Female singleton Xia Mei said that the burden of elder care would be doubled for the singleton couples, as husbands and wives would need to support parents from both sides: “Our singletons will have to care for four parents. When thinking about old-age care, it is better to have two children, so their burden can be lighter.”

Singleton Lin Jia said she longed for a sibling during both childhood and adulthood, but noted that her reasons for this had changed as she matured:

As a singleton, in the family, it's just one child faced with two parents, and my parents are getting older and older, and whenever it's the holidays or something's going on with the family, I would like to have someone with whom to discuss it … When I was little, I felt I would be very happy if I had someone to play with, like a very simple thought. Right now, I have that kind of feeling, like a more mature thought, which is that during happy times we could be happy together, and then, if there's a problem, we can talk about how to deal with it together and share the responsibility together.

Singleton Ma Hua said he had not yearned for a sibling as a child but realized how important a sibling would be as he grew older, and saw how difficult it was for singletons to deal with their parents’ illnesses, disabilities and deaths. He said:

When my friend's father passed away, he didn't have any siblings, and didn't have anyone to discuss decisions with. Take, for example, making decisions about the cremation and the funeral – he had to rely on his friend. Thankfully, he had such a friend. But, if he had a sibling, he could have, at the time, discussed things with them, even if it were just to get some ideas. It's like having a pillar. I thought that if something happened to my parents, and I had a brother or sister, I could discuss it with them. I wouldn't have to [make the decisions alone]. I feel that if I had to make these kinds of decisions on my own, I would feel uneasy if things went wrong, I would feel bad.

Singleton Jin Ni said she had wanted a sibling as a child because “my parents were very busy working while making me stay alone at home, and there was no one to play and talk with me, so it was too lonely.” As an adult, though, her yearning for a sibling changed focus: “Now that my parents are getting older, if there were two of us [siblings], caring for parents would be much easier. When one of us has trouble taking time off from work, the other could care for our parents.”

Singleton Xu Jun said he had yearned for a sibling as a child because “when I was bullied or wronged, I didn't have someone I could talk to about it. I couldn't talk to my parents about it, and could only talk to myself about it, and digest bad emotions myself.” As an adult, he said that “every day” he longed for a sibling to help share the burdens of elder care, because “like many others in China, I am a singleton, and now that I am married, I will have four elderly people [two parents and two parents-in-law] to take care of. Imagine how tired I will be! The pressure will be too great.”

Reflecting on his own experiences, singleton Qian Rui talked about the heavy stress many members of his own mostly singleton generation were already experiencing juggling career and family obligations. He worried that taking care of multiple elders would put an unbearable burden on the shoulders of already exhausted young adults. He said, therefore, that he wanted to have two children because he would not want to overstress one child by loading elder care burdens solely on that child:

One consideration [for having two children] is that when I am older, if there was only one child to take care of me, then he or she would be dealing with a career while also taking care of me. That would put too much pressure on his or her life, not only financially but also energy wise. He or she would have to spend a lot of time taking care of me, time which would otherwise be spent with his or her family. It would be too overwhelming for one person to deal with. This is why I hope to have two children because then they could at least share the burden.

Like many other interviewees, Qian Rui wanted his future children to pursue personal interests, happiness, upward mobility and success. He hoped that by sharing elder care responsibilities with each other, his two future children would have more time and energy to invest in their careers and children, and not be overstressed by filial obligations to provide nursing care and financial support for himself and his wife in their old age.

The Low Importance of the First Child's Gender on Desire for Two Children

There was a strong desire among previous generations of Chinese parents to have at least one son in order to continue the family line and provide elder care. Thus, parents in previous generations whose first child was a daughter were especially eager to have additional children.Footnote 39 Studies have found that in the late 20th century, parents of firstborn daughters were much more likely than parents of firstborn sons to have a second child, both in cases where the second child violated the one-child policy and in cases where parents qualified for one of the exceptions to the one-child policy and therefore could choose whether or not to have a second child.Footnote 40 Although studies of generations closer in age to that of our interviewees revealed a shift away from son preference and towards a preference for one son and one daughter, they still found a continuation of the importance of son preference for motivating Chinese parents to have second children.Footnote 41 However, only one of our interviewees mentioned a desire for both a son and a daughter as a reason for wanting two children. None of our other interviewees mentioned the gender of their future children as a factor that might influence their views about how many children they would wish to have.

The low importance of their future children's gender to interviewees’ views about the number of children they wanted was reflected in their written responses to survey questions asking explicitly whether they would want to have a second child if their first child was a son, and whether they would want to have a second child if their first child was a daughter. Most (69 per cent) of our 52 interviewees indicated that having a daughter was equally as good as having a son, and their preferences for one or two children were rarely linked to their gender preferences: 40 per cent indicated that they would want two children regardless of their first child's gender, and 46 per cent indicated that they would want one child regardless of their first child's gender (see Table 4).

Table 4: Fertility Desires Based on Child Gender Preferences of Childless Newlywed Respondents, 2012–2018

The insignificance of child gender as a factor for motivating our interviewees to want two children may have been partly owing to the fact that most of them are from urban areas where the cultural and economic imperative to have a son (for example, the need for a son to carry on the family name as well as provide manual labour, protection from crime and old age support) is not as strong as in rural areas.Footnote 42 It is also possible that because our interviewees were childless when they were interviewed, they had not yet experienced the yearnings that might result from having a first child who was not of the gender they preferred; in the future, after most of them have at least one child, we hope to look at whether and how the gender of their first child affects their desire to have a second child.

Conclusion

Unlike singletons in other societies, most of whose parents chose to have singletons without pressure from their governments and were likely to have made that choice based on pro-singleton values that were passed on to their singleton children, our singleton interviewees grew up in families that were limited to only one child by China's one-child policy, and not necessarily by their parents’ pro-singleton values. Most of our singleton interviewees therefore had negative views of their experiences growing up as singletons and wished that they had a sibling. Their desire for a sibling was closely linked to why they would rather have two children instead of one. They did not want their children to experience the unsatisfactory singleton circumstances they themselves experienced. Instead, they wanted their children to have the benefits of siblinghood that they observed among their own parents and older relatives as well as among the few siblings they knew from their own generation. Unlike singletons in other societies, who have been found to want and have lower fertility compared to their sibling counterparts,Footnote 43 our singleton interviewees were less likely than our sibling interviewees to want one child instead of two: 33 per cent of our 43 singleton interviewees, and 44 per cent of our nine sibling interviewees, were certain that they wanted no more than one child (see Table 3). In our survey sample, the proportion of singletons who wanted more than two children was also higher than that of those with siblings: 238 of our 369 singleton respondents (64 per cent) and six of our 15 sibling respondents (40 per cent) reported wanting more than one child.

When they were children, interviewees considered siblinghood valuable mainly because it could prevent loneliness and boredom. As adults, most interviewees who wished they had siblings yearned for the practical and emotional support that siblings could offer. They wished for a close family member who would have a greater understanding of the concerns of their generation than their parents had, with whom they could discuss the problems they faced and the tough decisions they had to make about work and family life. They also yearned for a close family member with whom they could share the burdens of caring for their aging parents and the responsibilities associated with making hard choices about their parents’ end-of-life care and funeral arrangements. They recognized that providing elder care would be one of the greatest challenges facing their generation as their parents grew older. Despite the development of old-age insurance policies, the inadequacy of pension coverage, insurance and paid nursing care continue to ensure that parents’ old-age support falls largely on the shoulders of adult children.Footnote 44 China's one-child policy, which transformed the family structure to a 4-2-1 pattern (four grandparents, two parents, one child), also imposed a daunting array of obligations upon the singleton generation which will be responsible for the care of up to six family elders. Our singletons felt keenly the contradictions between their belief that they would have primary responsibility for providing elder care for their parents and the intense commitments they would have to their own children and careers. Their yearning for siblings in adulthood was therefore even more common and intense than the yearning for a sibling that they had felt as children.

Unlike singletons in many Western societies who tend to want to have singletons themselves, many of our singletons said that their own lack of siblings actually caused them to want more than one child. Many singletons felt that the absence of a sibling had caused them to miss out on, and continue to miss out on, valuable experiences that they hoped their children would have. They therefore wanted to have two children so that their own children would not miss out on those experiences. It remains to be seen whether the valorization of siblinghood prevalent among our interviewees will cause most of them to actually take advantage of China's new two-child policy to have two children, as limitations in time, money and biology may yet prevent them from realizing those desires.Footnote 45 Our study's findings suggest, however, that regardless of actual fertility outcomes, the valorization of siblinghood and concerns about singleton status will continue to play an important role in motivating young adults born under China's one-child policy to want to have two children.

Acknowledgements

This material is based on work supported by the National Science Foundation under grants BCS-0845748, BCS-1303404 and BCS-1357439. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. The research for this article was also supported by a Beinecke Brothers Memorial Fellowship, an Andrew W. Mellon Grant, a National Science Foundation Fellowship, a grant from the Weatherhead Center at Harvard University, a postdoctoral fellowship at the Population Studies Center of the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Demography Fund Research Grant, a grant from the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, a National Academy of Education/Spencer Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship, a visiting fellowship at the Centre for Research in Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities at Cambridge University, a grant from the Harvard University China Fund, grants from the Harvard University Asia Center, a grant from the Harvard University William F. Milton Fund, and grants from Amherst College. We thank Benjamin Aliaga, Greene Ko, Marie Leou, Ruoxuan Xing, Jiajia Zhang, Siyi Li, Maggie Wu, Silvia Huang, Kelsey Chen, Kate Finnerty, Meizhong Hu, Justin Sun, Yajie Wan, Keren Yi, Daniel Choe, Yixiao Hou, Lianbi Ji, Zhiyuan Jia, Hannah Joyce, Sara Kaufman, Sabrina Lin, Lexi Ma, Christianna Mariano, Chun-Tak Suen, Nicole Trezza, Haelim Youn, Lindsay Yue, Angela Zhao, Edward Kim, Kari-Elle Brown, Ha Ram Hwang, Bowen Yang, Hanqi Yao, Yushi Shao, Chenxi Zhang, Patrick Liu, Sydney Scanlon, Angelina Han, Vivian Wei, Lee Jiaen, William Lu, Alexandra Sala, Lynn Fu, Birkley Lim, Agnes Han, Jemima Park, Dian Yu, Zhengyuan Fan, Yun Zhu, Dante Papas, Samuel Stallop, Rache Seifert, Emma Wilfert, Jiwoo Park, Ezra Alexander, Dahyun Jeong, Emma McCarthy, Grace Haase, Katherine Krosniak, Dana Frishman, Margaret Werner, Serena Lee, Rachel Kang, Hui Min Tan and Yanjun Zhu for their advice and assistance.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical notes

Cong ZHANG is an assistant professor of social development and public policy at Fudan University. Her research interest lies mainly in parenting, grandparenting, gender, families and kinship in China. Her publications have appeared in the Journal of Marriage and Family and Journal of Family Studies.

Aaron Z. YANG is a teacher at the Anuban Muang Chiang Rai School in Muang District, Chiang Rai, Thailand. He received his bachelor's degree from Amherst College in 2019.

Sung won KIM is an assistant professor of comparative education at Yonsei University. Her previous research on parenting, gender and education in China and worldwide has been published in the Comparative Education Review, Comparative Education, International Journal of Educational Development, The China Quarterly, The China Journal, Gender and Education, Ethos, Journal of Educational Psychology and Educational Review.

Vanessa L. FONG is a professor of anthropology at Amherst College. Her research focuses on longitudinal studies of Chinese childrearing. She is the author of Paradise Redefined: Transnational Chinese Students and the Quest for Flexible Citizenship in the Developed World (Stanford University Press, 2011) and Only Hope: Coming of Age under China's One-child Policy (Stanford University Press, 2004).