A key element in the “rise of China” narrative – and perhaps the most worrisome fact for many policymakers – is the sharp increase in Chinese military spending in the last two decades. According to official figures, China's military spending increased from 170 billion yuan in 2002Footnote 1 to 954 billion yuan in 2016.Footnote 2 This is an astronomical figure. But much remains unknown about how Chinese citizens view their government's military spending, and how they react to the “guns-versus-butter” trade-off. Do Chinese citizens prefer to spend more – or less – on the military? How do Chinese citizens want to divide scarce resources between domestic social programmes and military modernization? These questions have become increasingly relevant as China's economic growth slows and the tension between spending priorities increases.

To shed light on to these questions, we fielded a national online survey in China to study how its citizens perceive military spending. We found general public support for military spending that coexists surprisingly with anti-war sentiments and a significant strain of isolationism. The conventional wisdom suggests that nationalism should lead to higher military spending and more bellicose attitudes.Footnote 3 Our findings show, for the first time, that while Chinese citizens with a stronger sense of national pride support military investment, they also have stronger anti-war sentiments than other citizens.

Recent research suggests that the Chinese government is not immune to public opinion, even though public opinion does not transmit to policymaking through the same pathways as in democracies. This is especially so when the issue relates to livelihood or nationhood.Footnote 4 Previous findings suggest that public opinion can energize or constrain foreign policy in particular.Footnote 5 Furthermore, precisely because the opacity of the Chinese system makes it difficult for other nations to know for sure how the top leadership really thinks, objective information about how Chinese citizens think becomes a valuable resource. A deeper understanding of the Chinese public's preferences on military and foreign affairs may better inform China's neighbours of the strength of support for Chinese defence spending and the popular thinking behind it.

Our study was conducted in a period of economic slowdown. GDP growth has fallen from around 10 per cent to around 6 per cent since 2007,Footnote 6 and there are concerns that it might continue to drop to 3 or 4 per cent.Footnote 7 Consequently, as the national budget gets tighter, the competition between military and domestic priorities intensifies and the “guns-versus-butter” debate becomes more salient.

Existing Literature

Do Chinese citizens support military spending and what factors drive their preferences? Survey research on Chinese public opinion towards foreign affairs in the last decade has yielded many insights.Footnote 8 Attitudes towards military spending, or the “guns-versus-butter” trade-off, however, remain largely unstudied. An exception is Alastair Iain Johnston's survey of middle-class attitudes in the Beijing Area Study (BAS) in 1998–2002.Footnote 9 Although that research did not focus on military spending, one of the questions asked Beijing residents how they viewed military expenditure and found that the middle class was less enthusiastic than the average citizen. Meanwhile, a recent analysis of the BAS data by Jessica Chen Weiss found that a majority of Beijing respondents favoured increasing spending on national defence rather than on social welfare.Footnote 10

Our survey is based on a national sample beyond Beijing and covers a broad demographic spectrum beyond income and class. Chinese citizens today share a greater diversity of information in the public media – both old and new – than they did in the past,Footnote 11 fostering a public space where people articulate and amplify their views on policy issues.Footnote 12 It is in this expanded informational environment that our survey tests the demographic, economic and ideological correlates of attitudes towards military spending and the “guns-and-butter” trade-off.

Demographic and economic factors

Among the demographic factors, gender and age are frequently cited as influential in shaping attitudes to military affairs.Footnote 13 Surveys in Western democracies such as the United States, Canada, Britain and Israel have shown that male citizens are more supportive of military spending and combat deployments.Footnote 14 Previous research, however, is less clear about the effect of age.Footnote 15 Some studies suggest that older people are more likely to support military funding;Footnote 16 others have found no robust correlations.Footnote 17

Income and education are often linked to support for defence spending.Footnote 18 One argument is that people who depend more on government-funded social programmes are less supportive of competing priorities such as military investments.Footnote 19 Education has also been identified as a predictor of support in US and British surveys.Footnote 20 Louis Kriesberg and Ross Klein speculate that a better understanding of international affairs afforded by higher education may predispose people to support the military's role in global matters.Footnote 21

Political stances

Existing research suggests that conservatives, more than liberals, tend to view the world as perilous, which results in a heightened threat perception.Footnote 22 This disposition combines with preferences for order and social dominance to make conservatives more hawkish and more supportive of the use of military force.Footnote 23 Hawkishness may be defined (in contrast to dovishness) by a heightened suspicion of foreign rivals coupled with a greater readiness to use force and a stronger belief in the effectiveness of using force.Footnote 24

The relationship between nationalism and support for military spending has yet to be clearly established, partly because defining the concept of nationalism is contentious.Footnote 25 Rick Kosterman and Seymour Feshbach draw a distinction between patriotism, which involves an affirmation of loyalty and attachment, and chauvinism, which expresses a desire to dominate.Footnote 26 While chauvinism reduces inhibitions on the use of force, patriotism is more benign and may translate to lower levels of foreign policy assertiveness.Footnote 27 With these caveats, Peter Hays Gries and colleagues find that Chinese citizens who are nationalistic are more sensitive to US threats and prefer tougher policies.Footnote 28 Meanwhile, Donglin Han and David Zweig find that Chinese students returning from overseas are more internationalist than the middle class but no less likely to support the use of force.Footnote 29

Data and Findings

We fielded a national survey in May 2016 that covered all provinces and capital municipalities in mainland China. We contracted a survey partner to recruit a sample of 1,485 Chinese citizens to match the 2010 National Census adult population on gender, race, income and geography. Appendix 1, available in the online supplementary material, compares our sample with the census benchmarks. We fielded our survey over the internet in order to overcome two major obstacles. First, this enables us to cover all of China and collect data from diverse regions of an enormous country. Second, this allows for greater anonymity and enables respondents to answer questions in a relatively unobserved, self-administered setting. Existing research suggests that these factors can effectively reduce social desirability and self-censorship biases, which are important in a politically sensitive environment such as China.Footnote 30 The trade-off is that the online population may diverge from the general population in systematic ways and our sample may not be fully representative. However, because of institutional and infrastructural constraints on running political surveys in China, true probability samples of the national population are difficult to obtain at this point. Nevertheless, the online population is important in its own right. It accounts for more than half of the Chinese population, jumping from 4.6 per cent of the population in 2002 to 53.2 per cent in 2016.Footnote 31 Public online opinion is also known to be politically important to the government.Footnote 32

We measured individual preferences for military spending with the following question, which was adapted from the American National Election Studies (ANES).Footnote 33

Some people feel that the government should decrease military spending. Suppose these people are on one end of the scale, at point 1. Others think the government should increase military spending. Suppose these people are at the other end, at point 7. And, of course, some other people have opinions somewhere in between. Where would you place yourself on this scale?

Before asking the question, we provided a contextual description of China's economic condition and external security environment (randomized in both positive and negative terms). These randomized factors allow us to explicitly identify and control for the effect of perceived economic condition and external security environment when we gauge public attitudes towards military spending.Footnote 34

Military spending: more or less?

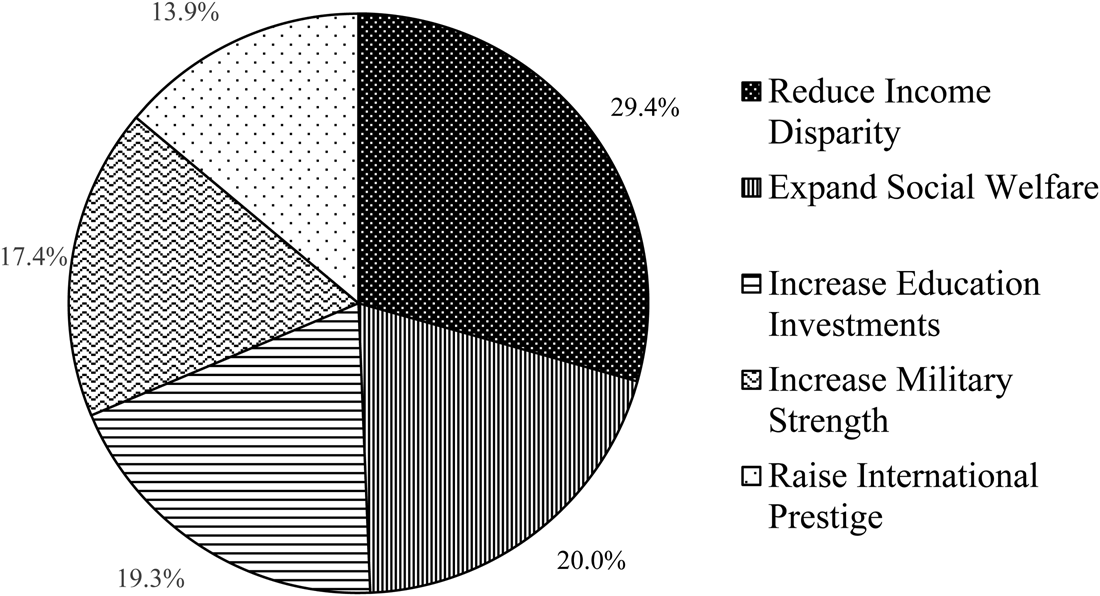

Chinese citizens generally support increasing military spending, as shown in Figure 1 in which higher scores indicate stronger support. The mean score is 4.7 (SD = 1.4, n = 1,484) on the seven-point scale. The distribution of responses is skewed towards support for increased military spending. Only a small minority of respondents (14.8 per cent) chose an option lower than the midpoint, indicating a preference for reducing military expenditure; 29.6 per cent selected the midpoint; 55.6 per cent (the majority) chose a response higher than the midpoint, conveying a preference for greater military expenditure. In addition, 27.6 per cent expressed a strong preference (six or seven) for increased military spending; in contrast, only 5.7 per cent indicated a strong preference (one or two) for reduced military spending.

Figure 1: Public Support for Increased Military Spending

Military strength as policy priority?

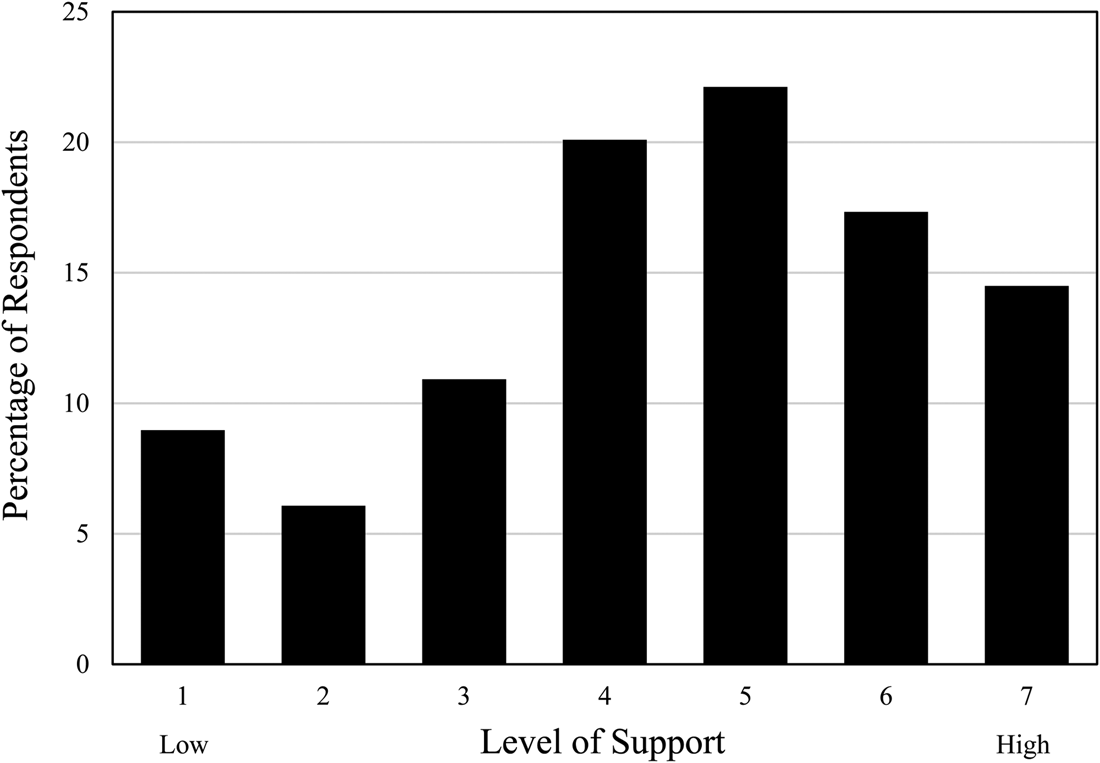

Although previous research has produced many surveys on Chinese public opinion, it has generally focused on attitudes towards either domestic affairs or foreign policy goals without focusing on the linkage or trade-off between the two domains. It is useful to calibrate preferences by placing them in a relative context. Thus, we test public support for military spending by comparing the importance of “increasing military capacity” against other policy goals. These goals included “expanding social welfare,” “increasing education investments,” “reducing income disparity” and “raising international prestige.” We asked respondents to rank these five policy options and checked how frequently respondents ranked “increasing military capacity” as the top or last choice. By doing so, we forced respondents to reveal their preference orderings when they prioritized among the different policy goals with the following question:

Please rank the following national goals from 1 (most important) to 5 (least important). You can change your rankings by dragging and dropping the relevant icons:

Figure 2 shows how often each of the five national policy goals was selected as the most important priority. Overall priorities focused on domestic goals rather than military capabilities when respondents were presented with a trade-off against other demands on the national purse. This result contrasts with the public support that military investments attracted in the abstract. Only “raising international prestige” (13.9 per cent) was chosen less frequently than “increasing military strength,” which was the top priority for only 17.4 per cent of the sample. Investments in social welfare and education were each ranked as the most important national goal by about 20 per cent of respondents, while the largest single group (29.4 per cent) proposed that ameliorating income disparity should be the nation's top priority. On the whole, public priorities appear to coalesce around non-military goals, with a significant majority believing that tackling domestic and social problems should be prioritized over efforts to enhance China's military power and international prestige.

Figure 2: The Public's Top Policy Priority

We also zero in on the 17.4 per cent of respondents who ranked “increasing military strength” as the top priority. We find that these respondents are more likely to support military spending and less isolationist than others. However, they are not significantly different in their attitude towards war avoidance. Appendices 4 and 5, available as supplementary material online, offer additional details on this subgroup, while the next section analyses the prevalence of isolationist and war-averse attitudes across all groups.

Is the Chinese public adventurist?

On the whole, the data suggest that while Chinese citizens support increased military spending, their policy priorities are inward-looking and domestically focused, rather than outward-looking or adventurist. To probe further, we measured the public's willingness to use force – an integral part of hawkishness – by asking respondents how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the statement: “The avoidance of war should be the most important principle in Chinese foreign policy.” We also measured preferences for isolationism by asking respondents how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the statement: “This country would be better off if we just stayed home and did not concern ourselves with problems in other parts of the world.”Footnote 35 Both measures used a seven-point scale from one (“strongly disagree”) to seven (“strongly agree”).

We find that most Chinese citizens believe war avoidance should be the chief goal of Chinese foreign policy, with a mean score of 5.2 (SD = 1.5, n = 1,484). As shown in Figure 3, a large majority of respondents (69.7 per cent) shared this belief, with only a small minority (11.9 per cent) who did not. Only 3.2 per cent disagreed strongly that war avoidance should be the most important principle in Chinese foreign policy.

Figure 3: “The Avoidance of War Should Be the Most Important Principle in Chinese Foreign Policy”

Public support for isolationism, shown in Figure 4, follows the same direction, with a mean score of 4.5 (SD = 1.8, n = 1,483). We detect a significant strain of isolationist sentiment, with the majority of respondents (53.9 per cent) favouring an isolationist foreign policy. However, there is also a sizeable minority (26.0 per cent) who disagreed with the isolationist majority. Only 9 per cent of respondents expressed very strong disapproval of an isolationist policy, in contrast to 14.5 per cent of respondents who expressed a very strong preference for isolationism.

Figure 4: “This Country Would Be Better Off If We Just Stayed Home and Did Not Concern Ourselves with Problems in Other Parts of the World”

Taken together, our results suggest that although Chinese citizens generally support military investment in the abstract, it is not a top priority for most people. Their policy priorities tend to be inward-looking, not outward-looking. A significant majority of Chinese citizens believe that war avoidance should be the most important goal of foreign policy, and many citizens feel that the country is better off disengaging from the rest of the world. This suggests that the Chinese public may be more isolationist than adventurist.

Correlates of preferences

We further test whether the demographic factors identified by previous studies correlate with preferences for isolationism, war avoidance and military spending, using ordered logistic regression. On education level, we divide our respondents based on whether they have a bachelor's degree or higher degree.Footnote 36 National pride is measured using the question: “Are you proud to be a Chinese citizen?” with a four-point scale from “not proud at all” to “very proud.”

We find that males are significantly more supportive of increased military spending than females. Older respondents, as well as those with high income and strong national pride, also tend to be more supportive of military spending. We repeat the same analysis for war avoidance and isolationism. Respondents with high income and strong national pride report stronger war-avoidance sentiments, while respondents who are older tend to be more isolationist. Note that although the effect of a university education on war avoidance is statistically significant in the multivariate ordered logistic regression, the result is not robust. Appendix 3 in the online supplementary material compares the ordered logit results across different model specifications.

Conclusion

We find that Chinese citizens support military spending in the abstract; however, military spending is not a top priority for most people, who are generally domestically oriented. Public support for military spending is coupled with a domestically oriented worldview and an emphasis on war avoidance as the key goal in foreign policy.

It is notable that widespread anti-war sentiments coexist with public support for military spending. We think there are at least three possible reasons to explain this phenomenon. First, it may be that Chinese citizens see their military force as mostly defensive, or as Weiss points out, they may expect that funding a large military will deter challengers and strengthen coercive diplomacy, rendering military use in action less necessary.Footnote 37 In other words, those who may be willing to pay for the military may not actually wish to use the military. The second possibility is media socialization. The Chinese government often frames its foreign policy actions around a rhetorical emphasis on peace and stability, even when some of these actions are assertive in nature.Footnote 38 Because the media discourse places a rhetorical premium on peace, the same attitude might have permeated into public consciousness. The third possibility is that our survey question on anti-war sentiments is a question about general principle rather than a specific categorical imperative. Thus, even if a citizen believes that war avoidance should be the most important principle in foreign policy, it does not mean that he or she would be averse to the use of force when it is necessary to protect the country's core interests, such as security or prosperity.Footnote 39 While it is beyond the scope of the current study to determine the validity of each possibility, we believe that disentangling and testing the different logics will be a useful avenue for future research.

Our survey captures contemporary attitudes and aspirations on military spending following a period of considerable social, economic and technological change in China. Recent research suggests that the Chinese government is not insensitive to public opinion, even though the mechanisms of accountability may differ from those in democracies. The government is particularly sensitive to public sentiments on issues invoking nationalism,Footnote 40 and previous research suggests these sentiments can potentially influence policymaking.Footnote 41 Insight into how the public would like government to conduct its foreign policy may reveal to concerned observers the strength of public support for Chinese military spending and the rationales behind it. In particular, our findings offer an important nuance with regard to other research suggesting that hawkish views are widespread among Chinese citizens.Footnote 42 Although the Chinese public may exhibit high levels of national pride, this does not necessarily translate into bellicose attitudes.

Because there are limitations to what we can learn from a single survey, it will be useful for future studies to replicate and further investigate the nuanced relationship between nationalism and bellicosity. In particular, one dispositional factor calls for future research. While Gries and his colleagues find that Chinese patriotism aligns with a benign attitude towards the US, we find that those who exhibit stronger national pride also prefer increased military spending.Footnote 43 This speaks to the relationship between patriotism and foreign policy assertiveness and suggests the connection may be more nuanced than previously thought. Future studies may explore whether those who are more proud of their nation are also more attentive to and knowledgeable about the domestic and foreign implications of military spending; more attracted by the power and prestige that a strong military bestows; or more inclined to perceive the Chinese military as a protector of regional peace and stability.

Another avenue for future research is the impact of the “guns-versus-butter” trade-off. The rapid development of China's military power over the past two decades has been built on the basis of unprecedented economic growth. However, an economic slowdown is likely to undermine this foundation over time. Our survey reveals a more isolationist worldview that clearly prefers government investment in domestic priorities over international issues. This preference brings into question whether public support for military expenditure can be sustained if economic growth rates continue to fall at the same time as domestic needs continue to rise.

Biographical notes

HAN Xiao is a PhD candidate at the University of Hong Kong. His research focuses on Chinese military doctrines since 1949.

Michael SADLER is a PhD candidate at the University of Hong Kong. His research focuses on the efficacy of military reassurance.

Kai QUEK is an associate professor at the University of Hong Kong. His research areas include signalling theory, crisis de-escalation, and the nature and consequences of Chinese nationalism.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741020000260.

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their useful feedback, Mengqiao Wang, Jiaqian Ni, Samuel Liu and Eddy Yeung for their assistance, and the University of Hong Kong for financial support. The usual disclaimer applies.

Conflict of interest

None.