China's economic reforms since the late 1970s have been a dramatic negation of the country's former socialist economic system.Footnote 1 The mid-1990s witnessed the large-scale privatization of state-owned enterprises, which resulted in the layoffs of 26.8 million state workers.Footnote 2 Meanwhile, sweatshops mushroomed in urban coastal regions, attracting millions of rural migrant workers from the near-bankrupt countryside.Footnote 3

As China's urban economy continued to boom, its migrant population experienced unprecedented expansion, growing from 79 million in 2000Footnote 4 to 281.71 million in 2016,Footnote 5 becoming the dominant portion of China's working-class population. Among the 169 million “going-out” rural migrants (waichu nongmingong 外出农民工) in 2016, over 80 per cent worked in urban areas predominantly engaged in manual labour, with 50.2 per cent being employed in manufacturing and construction and 46.7 per cent in the service industries.Footnote 6 To distinguish them from workers under the old socialist system, some scholars call these migrant workers “China's new workers.”Footnote 7

They are “new” workers because unlike the “old” socialist workers, who were entitled to a full range of benefits in healthcare, housing, education, job security and political power, rural migrant workers enjoy little labour protection and endure long working hours, subsistence-level wages and harsh working conditions.Footnote 8 These “new workers” have made significant contributions to China's reform and growing competitiveness in the global market but are locked near the bottom of the production chain.Footnote 9 The term “China's new workers” belies the bitter struggles these rural migrant workers face.

Despite their numbers, rural migrant workers rarely take collective actions to protest against the injustices they experience. Instead, their forms of resistance are usually individualistic, such as changing jobs. Yet, as Jenny Chan and Ngai Pun conclude in their study of migrant industrial workers in south China, collective action is the central element for class formation.Footnote 10 Although an increasing number of rural migrants choose legal approaches and labour movements to protect their rights and interests, passive reactions in response to social inequalities are still prevalent among migrant workers,Footnote 11 demonstrating a lack of consciousness of their collective class fate.

This study aims to address the dearth of literature on the formation of migrant workers’ class consciousness. It does so not by focusing directly on migrant workers but rather on the state of class consciousness among migrant children. Research shows that the formation of one's consciousness of class structure can begin long before one enters the workplace.Footnote 12 Children of five to eight years of age are already aware of the inequities between rich and poor and associate having wealth with having a good job, good luck and personal merit.Footnote 13 From the age of eight onwards, children can classify and order social classes based on their understanding of occupational hierarchy.Footnote 14 As children grow up, they increasingly attribute social stratification and economic inequality to personal traits such as education, ability and effort.Footnote 15 Beyond 12 years of age, children are able to build a moderately elaborate picture of society and of the relationships between individuals and social structures.Footnote 16 The images of society and class structure constructed in one's childhood can be fundamental elements of the more explicit forms of one's class consciousness.

Most importantly, children of rural migrant workers in China are highly likely to reproduce their parents’ working class position when they join the workforce.Footnote 17 In Yingquan Song, Yubiao Zeng and Linxiu Zhang's five-year longitudinal study of 1,866 junior secondary school students in 50 migrant schools in Beijing, it was found that less than 40 per cent of students went on to high schools or vocational schools, and less than 6 per cent were admitted to university; most remained in Beijing, working for a pittance or merely walking the streets.Footnote 18 Therefore, it is of great importance to understand the state of class consciousness of migrant children, as they will become the new generation of migrant workers and their mindsets are malleable and open to new possibilities of class construction. Inquiries into migrant children's social consciousness could offer a window on the genesis of adult migrant workers’ class consciousness.

The Literature on Rural Migrant Children

The increasing population of rural migrant children makes it a group that China cannot afford to ignore. In 2015, there were 34.26 million migrant children (aged 17 or younger) in China, accounting for 12.6 per cent of all children aged under 18.Footnote 19 Much research has documented the hardships they encounter, including unequal access to urban public education,Footnote 20 discrimination in urban schools (if, indeed, they are admitted in the first place),Footnote 21 and various forms of social marginalization in host cities.Footnote 22

Most extant literature identifies the hukou 户口 (household registration) system as the primary cause of the miseries endured by migrant children and families.Footnote 23 The hukou system mediates the distribution of public goods and entitles citizens to social welfare provision based strictly on their registered place of legal residence, rather than the location of their current home. Although it is not impossible to change hukou status, it is rarely achievable for rural people.Footnote 24 Therefore, most rural migrant workers and their families are not eligible for urban hukou status and the associated social welfare benefits, despite the fact that they live and work in urban centres. Hukou status greatly disadvantages the migrant population, severely restricting their access to local public resources in host cities, including school education. Without local hukou status, rural migrant families must overcome formidable institutional hurdles including, for example, the five-certificate (wuzheng 五证) policy in BeijingFootnote 25 and the points-based school enrolment (jifen ruxue 积分入学) system in ShanghaiFootnote 26 in order to enrol their children into public schools. Hukou status appears to be the biggest obstacle preventing rural migrant children from accessing public education in cities.

Upon closer examination of school enrolment requirements, however, there appears to be a distinct shift from exclusion by hukou to discrimination by class. Under these policies, educational opportunities for migrant children are no longer restricted by hukou per se but are contingent upon migrant parents’ educational level, employment status and economic means.

In Beijing, for example, some documents (for example, proof of employment and proof of residency) require the individual to have stable employment with enough income to secure decent housing; however, most employers of migrant labour fail to provide such packages. In 2007, only 10 per cent of migrant workers had access to medical insurance, 11 per cent to unemployment insurance, and 18 per cent to pensions.Footnote 27 By 2016, 64.9 per cent of rural migrant workers were still found to be working without legal labour contracts with their employers, and 2.37 million rural workers had wage arrears amounting to 27.1 billion yuan – an average unpaid wage of 11,433 yuan per person.Footnote 28 Also, in Shanghai's points-based hukou system, applicants who receive 120 points are qualified to apply for one public school place. Within this system, having a doctoral degree earns 110 points, while each year of social insurance payment is worth three points.Footnote 29 Clearly, such a points structure favours middle- or upper-class migrants with higher education credentials, steady employment and legal labour contracts. Most migrant workers’ harsh employment conditions, however, prevent them from accessing Shanghai's public resources and clearly fail to provide them with the prerequisites demanded for their children to attend public schools.

Rural migrant children are indeed excluded from urban public schools by both hukou status and family socio-economic status. Labour market status functions as a replacement for hukou and as a less overt barrier to migrant children's education. The complexity of this new scenario poses challenges to the explanatory power of the hukou discourse, which loses sight of the critical class effects in rural migrant children's adversities.

Moreover, the predominant hukou discourse confines the explanation of rural migrant children's social consciousness to the rural–urban dichotomy. Much effort has been invested to document migrant children's identity crisis, as they are trapped between urban and rural societies.Footnote 30 Rural migrant children inherit their parents’ rural origins but most have only a weak attachment to rural life.Footnote 31 Living in cities for years or even since birth, they identify much more with the urban lifestyle but feel unaccepted by urban society, owing to various discriminations.Footnote 32 In these studies, rural or urban identity is the only marker available for rural migrant children and the main conflicts are conceived as being between migrants and locals. This binary view of migrant children's subjective world largely ignores their daily exposure to the class-based inequalities experienced by their families. Research is needed to expand concepts of rural migrant children's identity and must include the important dimension of class.

In sum, hukou or the rural–urban distinction tells half of the story of rural migrant children, and the prevalence of the hukou discourse conceals rural migrants’ lived experiences of class conflicts. It is therefore of paramount importance to include class in migrant education research and to expand the narrow, yet dominant, framework of the rural–urban binary.

False State versus Critical State of Social Consciousness

This study borrows Paulo Freire's framework of false and critical consciousness.Footnote 33 The state of false consciousness contributes to the reproduction of the exploitative relationship between the capitalist and working classes. With false consciousness, workers fail to recognize their exploited status and the possibility of transforming the social structure. They therefore tend to adopt accommodative strategies in reaction to class inequalities and social oppression.Footnote 34 The state of critical consciousness, in contrast, enables people to penetrate the systematic mechanisms of exploitation and domination and identify common interests within their own class. With critical consciousness, oppressed workers transform their individualistic resistance into collective actions that embed individuals’ futures into the shared destiny of their class.Footnote 35

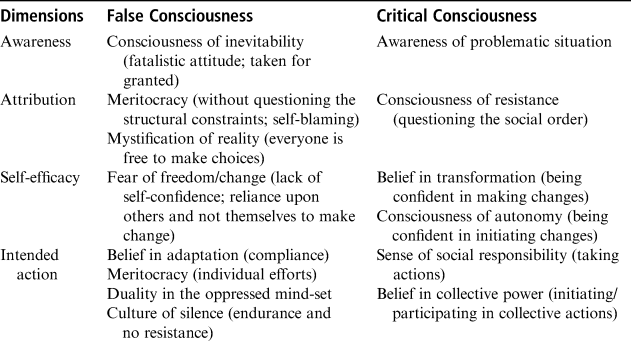

Four dimensions emerge from Freire's studies to distinguish the critical consciousness from the false one (see Table 1).Footnote 36 The first dimension, awareness, refers to people's understanding of their current situation and whether they can recognize the problems in their current social reality. The second, attribution, refers to how people perceive the social, economic and political causes that perpetuate the inequalities and injustice they face in society. The third dimension, self-efficacy, involves whether people believe in their ability to bring changes to social and political conditions, while the fourth dimension, intended action, concerns people's beliefs about how to act to make changes.

Table 1: Dimensions of Social Consciousness Based on Freire's False/Critical Consciousness Theory

These four dimensions set up important parameters for understanding the state of migrant children's class consciousness. Grounded in this four-dimensional framework, this study seeks to answer the following three research questions. Are migrant children aware of the class position of rural migrant workers? To what causes do they attribute the injustice encountered by migrant workers? Finally, whom do they see as change makers and what do they see as feasible ways of changing their fate?

Methods

This study chose Beijing as its research site. As China's capital and one of its mega-cities, Beijing has a large migrant population and a large migrant child population. Of Beijing's 21.5 million residents in 2014, 38.1 per cent were migrants,Footnote 37 including over 480,000 rural migrant children of compulsory-education age.Footnote 38

Qualitative investigations were conducted in two primary schools – one migrant school and one public school – in the Sun district (pseudonym) of Beijing between June 2014 and January 2015. The migrant school was situated in a predominantly migrant community and offered affordable education for 484 migrant children who had been excluded from public schools in Beijing. In the public school, 90.1 per cent of all students were rural migrant children whose families had somehow succeeded in presenting the five required documents for enrolment. The public school was staffed by certified teachers, whereas the migrant school could only hire temporary teachers, most of whom lacked professional training.

Student participants were recruited from the two schools’ fifth and sixth grades, the highest two primary school grades in China. Fifth and sixth graders in China are usually 10 to 12 years of age and can, according to psychologists, construct a moderately elaborate conception of class structure.Footnote 39

Data were drawn from questionnaires, interviews and observations conducted in the two schools. Informed consent was obtained from principals, fifth- and sixth-grade teachers, parents and the children before the investigation began. First, a student questionnaire was distributed to the children to garner information about their family backgrounds and their perceptions of their lives in the family, school and community contexts. A total of 324 of the 382 returned student questionnaires were valid (see Table 2 for respondents’ characteristics).Footnote 40 Data generated from the questionnaire helped to identify and reduce idiosyncratic findings from interviews, serving as an effective means of triangulation.

Table 2: Respondents’ Demographic Information

Notes: a There may be discrepancies between their responses and the actual length of time they spent in Beijing (probably higher than the real data); b student interviews revealed that the income of self-employed parents usually fluctuates widely in reality; c employee includes highly educated professionals, technicians and skilled workers; d self-employed occupation refers to those who are not involved in a formal, traditional employer–employee relationship and who are self-employed, such as small business owners, street peddlers, individual-contracting workers, garbage collectors and so forth.

A total of 87 fifth- and sixth-grade students (43 from the public school and 44 from the migrant school) participated in the interviews. The interviews followed a semi-structured protocol to explore the children's beliefs, values and attitudes towards social problems, class-related issues and school education. To ensure that they felt safe when discussing issues and sharing their opinions, students could either nominate the students with whom they would be interviewed in a focus group or choose to be interviewed individually. Based on the children's choices, seven individual and 25 focus-group interviews were conducted at the schools by one of the authors. The interviews lasted from 45 to 90 minutes, depending on group size. Focus-group interviews enable participants to listen to others’ opinions and allow the researcher to observe how participants respond to and utilize others’ ideas and understandings to form their own.Footnote 41 In this study, the focus group activated multiple peer inputs on the same topic, stimulating richer and deeper conversations among the migrant children. It proved to be a more efficient approach to data collection than the individual interviews.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim. Earlier transcripts, field notes and documents were coded and analysed throughout the data collection process to inform subsequent interviews and observations. Patterns of children's perceptions were explored using Friere's four constructs of social consciousness (awareness, attribution, self-efficacy and intended action). Self-efficacy and intended action were combined into one section (“possibility of changes”), owing to the high degree of overlap between the two dimensions in the children's responses.

Results

Awareness of class position

To understand their perceptions of migrant workers’ social positioning, the interviewed rural migrant children were asked to define the word gongren 工人 (worker) and to describe their parents’ occupations. Of the 87 migrant children, 69 perceived gongren to be people who engage in physical labour, including manual workers (carpenters, construction workers, plumbers), service and sales (cashiers, salespersons, drivers, cooks) or even small bosses (street peddlers, corner shop owners, leaders of construction groups). Over 60 per cent of these migrant children's fathers fell into these categories. The children described these jobs as “tiring,” “working from dawn till sundown” and “dirty,” and recognized that they were characterized by “low wages” or “wage arrears” and “being looked down upon.”

In addition to defining the nature of work, the migrant children also naturally paired the concept of “workers” with the concept of “bosses” (laoban 老板). Workers were seen as selling physical effort (mai liqi 卖力气) and bosses as spending money to hire workers, indicating that migrant children at this age already identify major categories of class.

The migrant children were fully aware of the power relationship between workers and bosses, perceiving the former as inferior to the latter: “boss and worker are like the superior and the subordinate. The boss has many people on hand and urges them to work” (student No. 2); “[workers] have to do whatever the boss asks them to do” (student No. 68); “[workers’ jobs are] very tiring, and I always feel workers depend on bosses for a living” (student No. 77); “Workers work for the boss, [and must be] obedient to the boss” (student No. 80).

The rural migrant children also observed instances of injustice in the employment relationship. Student No. 86, for example, recounted his mother's experience:

Workers are bullied [by the bosses], [who] hire workers and ask them to work. After that, bosses no longer take care of workers … My mum has done woodwork every day for five or six months. But the boss does not pay her anything. [The boss] sold the products but paid nothing to workers … My mum keeps working there… [and so] did the other workers.

Another student (No. 78) mentioned an incident she had seen on TV:

A man got hurt at work, but his boss would not pay him his wages and denied him any compensation. At last, the man went to the hospital himself and when he asked his boss to pay his wages, the boss ran away.

Of the 324 questionnaire respondents, 56.2 per cent reported that their parents sometimes or often told them about conflicts in the workplace, while 22 interviewees confirmed that they had seen or heard about unfair incidents happening to their parents or relatives. This implies that such labour right violations were daily experiences lived by some migrant children; inequality and injustice in labour relations were so prevalent in migrant children's lives that awareness of their parents’ class position was simply a part of their growing up.

Attribution of workers’ inferior position

In the questionnaire, migrant children were presented with a scenario in which an imagined worker working in a shoe factory had a salary so low that he could barely feed his family and raise his child. The migrant children were asked to select one of five options as the primary reason for the adversities in this worker's life. The result disclosed a conspicuous divide among the children, with close to half (46.6 per cent) attributing the shoe worker's hardship to his “not studying hard enough at school” and almost as many (46.1 per cent) pointing to “the boss not paying enough” as the chief cause.Footnote 42 Individuals’ qualifications and the employment relationship were seen as the top two reasons for workers’ disadvantaged class position.

The interviewed children articulated the same two primary causes. First, over half of the 87 student interviewees attributed workers’ being manual labourers to their earlier educational failures. As student No. 19 from the public school said, “workers’ jobs are tough … because they didn't study well in school and have low educational attainment.” People without educational credentials were seen as unqualified for high-skilled jobs. Thus, manual labourers were considered as “not as smart as their bosses” (student No. 86) and “uneducated” (student No. 69) – or, as students No. 31 and No. 87 put it, “workers do not have the same ability as the bosses, who use their minds” and “if workers had done well in school, they would not have ended up doing manual jobs like [they do] now.” In other words, workers were trapped in manual labouring jobs because of their educational failures. Ultimately, the children believed that the economic plight of the working class stemmed from such workers being limited to manual labouring jobs, a situation which the children believed could be avoided by school success. Their responses placed the blame for class inequality squarely on the workers themselves.

The children also attributed workers’ hardships to their employers; however, rather than blaming the exploitative employment regime per se, rural migrant children in this study saw two kinds of bosses, good ones and bad ones. They blamed the bad bosses for poor treatment of employees and regarded workers to be unlucky if they fell into the hands of such bosses. From their perspective, workers could choose to change jobs until they were “lucky enough” to find a good boss:

Some bosses are really kind people … But there are some bosses who are rich but really bad. They have so much money but are still mean to others. (Student No. 28)

[Workers] can choose to work for you or not. They can decide to quit this job and work in another factory. In the end, they will find a factory somewhere not like this place [with wage arrears and poor working conditions]. (Student No. 54)

In line with the students’ belief in the “good boss” concept, wage arrears were deemed to be the result of employers experiencing a shortage of funds. Accordingly, workers with wage arrears issues should understand their employers’ difficulties and give them time to find money for workers’ wages:

If the boss does not have money now, not receiving wages for a while is fine. (Student No. 26)

It is definitely not because the boss does not want to pay workers’ wages on time. It must be a funds shortage problem … They will pay the wage immediately when they have enough money. (Student No. 40)

In short, the causes of the social injustices encountered by migrant workers were seen as owing to individual factors. Workers ended up in manual labour jobs because of their personal failures at school, and it was only their own bad luck if they came across “bad bosses” who violated their labour rights. These migrant children had developed an emerging interpretation of social classes which was overwhelmed by the ideology of meritocracy and individualism but precluded criticisms of the systematically exploitive employment relationship.

Worth noting also is the migrant children's strong sense of the rural–urban divide in urban society. According to student No. 9, a girl from the public school, “many people, like my neighbours, always say that the locals look down upon migrants, and bully them.” Once, she witnessed a man come into her parents’ convenience shop begging for a free beer, because his boss had not paid him anything for almost two months. Although “he did not say whether he was local or migrant,” she believed the man was a rural migrant who was being bullied by his Beijing employer. Student No. 78 angrily described having witnessed street peddlers being expelled from an area by a rude city inspector, even though the peddlers had done nothing wrong. The students’ common experience of being marginalized in urban society reinforced their collective identity as migrants, highlighting local–migrant boundaries but clouding their burgeoning class awareness.

Possibility of change

Seeing manual work as the root cause of poverty and lack of status, the children in this study rarely aspired to do manual work even though the majority of their parents worked in such jobs. To some children, being a worker was shameful and caused a loss of face. Two boys from the public school illustrated this in the interviews:

If I finally have no choice, I may be [a worker] … [Then,] I will keep my mouth shut, wear a mask … [I] do not want other people to see me [doing it]. (Student No. 31)

Being a worker, you may be looked down upon sometimes. And then, your friends may laugh at you when gathering together at a party. (Student No. 43)

Refusing to follow in their parents’ footsteps, the rural migrant children stated they wanted to change their fate by working as highly educated professionals, company owners and government officers – white-collar positions that generally require university credentials (see Table 3).

Table 3: Respondents’ Expectations of Future Occupations

Conscious of the significance of education, rural migrant children displayed a strong desire to pursue tertiary education and a firm belief in individual meritocracy. For instance, student No. 15 stated:

[S]tudying is for our own future. Learning well can help me enter into a key point middle school, then key point high school, then first-class university … it will be easy for me to find a job and get a high salary with my university degree.

The survey found that 65.9 per cent of the 308 respondents expected to go to university in the future. These migrant children believed that gaining an education was a crucial means to changing their fate and avoid living what they saw as the pitiful, shameful lives lived by their manual-labouring parents. However, over 30 per cent of the survey respondents had lost hope of ever gaining a higher education as early as in primary school, and instead they planned to either enter the job market directly or attend vocational school after middle school.

In addition, migrant children hoped employers, particularly good ones, would make a difference to their future if they did eventually have to join the manual labour force. Their top strategies for success were “enduring hardship” and “pleasing employers through hard work.” Sometimes, it would not be enough to “accept wage arrears” and some students, like student No. 83, said they would need to “endure [their] superior's hitting and cursing,” and hope that “the boss would trust us and be happy. If [the bosses] are pleased, they may promote us and increase our salaries.” Moreover, some migrant children expected their future employers to be open to negotiation about working conditions. Student No. 77 imagined suggesting to her future bosses that they set up a suggestion box to collect workers’ views:

After seeing lots of suggestions [on the same issue], the boss may know the problem and decide to increase our salary. [Otherwise,] if [the boss] disagrees with our [wage] request and thinks we are dispensable [to the company], we cannot do anything but endure the hardship.

These children imagined that they would be able to persuade their future employers to improve their working conditions. Failing that, they stressed that “voting with their feet” would offer a way out – i.e. they would leave the bad bosses in search of nicer employers who would offer better treatment:

If my boss failed to pay my salary on time, I think I would quit the job and seek another company. (Student No. 39)

The children's responses indicate that they believed that it was the bosses who were the change makers, not the workers. Thus, for some migrant children, receiving fair treatment as workers or employees was not their goal; instead, they believed that the best way to alter their fate was to become a boss. In interviews, 29 students mentioned having a “boss” dream. For example, student No. 48 described what he wished for his future: “I would like to start my own company … Actually, we all want to be the boss because the boss doesn't have to live a tough life.” The work of a “boss” was perceived to be the polar opposite of their parents’ manual labour. Bosses spend their time “sitting in the office” (student No. 63), “watching TV, drinking tea, making phone calls” (student No. 35), or “writing something or typing on the computer” (student No. 31), while “just collecting money and asking others to work for them” (student No. 68). In the children's eyes, the boss was more powerful and cleverer than the workers; however, this “boss” dream could only be realized through individual hard work.

Although the children had high expectations of bosses, they were not ignorant of alternative resistance or bargaining strategies. They did mention alternative worker responses to labour conflicts, including slacking off while working (five students), violence and sabotage (nine students), and seeking help from lawyers and police (25 students). Collective actions such as strikes and protests were mentioned by 19 students, suggesting an emerging awareness of collective actions among the migrant children. However, 37 of the 87 interviewed migrant children explicitly disapproved of going on strike for higher wages. This was because strikes cause trouble for “good” bosses and irritate the “bad” ones:

I think we should not go on [strike or protest]. Bosses have their reasons for not paying wages [on time], like a shortage of money. If you go on a strike, you will add to the employer's burden. (Student No. 40)

It is completely wrong [to request a salary increase through strikes]. Big bosses are always nice and generous. They will not be mean to [workers]. I will not participate in strikes. (Student No. 46)

Some students even perceived workers’ protests and strikes as “violence” that “disrupted” the social order and jeopardized public safety. This rejection of collective actions emphasizes the popular view among migrant children that workers owe their well-being to the mercy of their bosses and are dependent on bosses for their living. Their awareness of the constraints and dependency of workers reinforced their belief that workers must be obedient and tolerate injustices. Their rejection of workers’ collective actions revealed that the migrant children had yet to develop critical consciousness.

In sum, the migrant children subscribed firmly to the ideologies of individualism and meritocracy, which confirms the rising trend in individualization in China that has personal effort and self-reliance as its hallmarks.Footnote 43 Placing blame on the individual characteristics of workers or bosses for workers’ inferior socio-economic conditions conceals the exploitative nature of the class structure from the children's awareness.

Discussion: Family and School Influences

The false consciousness presented in the children's responses might be disappointing but is by no means surprising. Rural migrant children have been naturally exposed to cases of labour exploitation and oppression by directly observing their parents, relatives and neighbours in their surrounding migrant communities, so they are aware of the unequal class relationship. However, being aware of class exploitation is one thing; critical analysis of the situation is another. For a critical consciousness to emerge, children need opportunities to access critical interpretations that debunk the myths of meritocracy and separate systematic exploitation from individual morality. Such opportunities are, unfortunately, scarce or even entirely unavailable to rural migrant children. Instead, the dominant ideologies of individualism, meritocracy and the devaluation of physical labour prevail in their family and school environments.

At home, migrant parents’ passive acceptance of their bosses’ labour abuses – as demonstrated, for example, by student No. 86 who viewed his mother's salary arrears and continued working as “normal” – could send their children the message that workers are weak and have no choice but to swallow the abuse and endure.Footnote 44 Workers’ obedience is probably a carefully weighed action, selected from limited alternatives. Legal or collective actions are too costly or too risky.Footnote 45 Unskilled or semi-skilled workers, situated at the bottom of the labour market, are left to choose between salary arrears or no salary at all. The migrant parents’ low self-efficacy betrays the massive political and legal machineries behind the exploitative labour relations that force labourers to “voluntarily” accept unfair working terms. The resignation and passive attitude of the migrant parents endow their children with a sense of life's limitations and erodes their children's self-efficacy from a young age.

Not in a position to change their own social positions, migrant workers, like many other Chinese parents, pin their hopes on their children.Footnote 46 Most of the migrant children interviewees’ parents had attained no more than a secondary education (79.3 per cent for fathers; 82.8 per cent for mothers), but made every effort to enrol their children in Beijing schools with the expectation that the better education provided in cities, compared with that in rural areas, would allow their children to forge a different career path and avoid a life of physical labour. The children confessed:

[Our parents] hope we study well. My parents want me to attend a good university and then find a good job, and not work as hard as them. (Student No. 33)

My mum keeps telling me every night that I have to study hard. Otherwise, I will be like mum and dad, doing hard manual labour. (Student No. 87)

With no collective action in view, education is perhaps the best chance migrant children have.Footnote 47 Nevertheless, echoing previous research, the parental expectations in this study affirmed the myth of meritocracy and the prejudice against physical labour in the minds of migrant children.Footnote 48

Outside the family, schools play a pivotal role in shaping children's social consciousness.Footnote 49 The author has discussed elsewhere that teachers at the two case schools approached inequality issues differently but were all committed to the ideology that “education changes destiny.”Footnote 50 The public school was reluctant to address inequality topics with its students, as its principal Qiao believed that “although the society itself is not that healthy and not pure, children should grow up in a pure environment” and that the negative side of society should be filtered out of the formal school curriculum since “we do not have to bring those social problems in front of [migrant children].” Despite this good intention, teachers in the public school admitted it was impossible to entirely hide harsh social realities from the children. Occasionally, problems like wage arrears, public school exclusion and protests by rural migrants were raised in school by the students themselves. Some teachers responded that these hardships were part of the cost of migration. Accepting marginalization and exploitation was articulated as a necessary sacrifice that migrant workers had to make when choosing to come to Beijing. Again, many labour issues were viewed from the perspective of the migrant–local/rural–urban dichotomy. In general, the rural migrant children in the public school were unlikely to lend themselves to a critical analysis of their own lives.

In contrast, the migrant school's teachers were active in discussing inequality issues. Class teachers were encouraged to lead student discussions on topics like the “documents needed for public school enrolment in Beijing” and the “lack of Beijing student status (xueji 学籍) in the school.” Unfortunately, the analyses were also dominated by the hukou discourse. For instance, discussions on the former topic centred exclusively on discriminatory government policies based on hukou identity, failing to note how unfair labour conditions constrained migrant families’ capacities to obtain the documents. In both the public and migrant schools, students more readily adopted the rural–urban or migrant–local discourse for causal attribution.

Labour issues were rarely addressed in either school, save for a few exceptions in the migrant school. Once, a volunteer teacher took a special interest in migrant workers’ labour conditions, sharing news with students about a series of worker suicides in Foxconn, a leading manufacturer of hand-held electronic devices in Asia. To his disappointment, the students were indifferent and asked why the workers had to work for others instead of starting their own businesses. The teacher had no good way to respond and so dropped the discussion. In other cases, some teachers used students’ parents, who were small business owners, as positive examples to persuade the class to study hard. Although migrant teachers in Beijing were found to be suffering from the same precarious and poor working conditions as rural migrant workers, they lacked the perspective of class either to analyse their own labour situation or to enlighten the children.Footnote 51 These cases indicate that teachers in general may be ill-prepared to address class issues in their teaching.

Further, both schools inculcated the hierarchical conception of occupations in students and emphasized education as the path to individual mobility. Good academic performance was perceived as the stepping stone to decent, professional work in the future and an escape from manual labour. As one class teacher from the migrant school said in an interview:

[I said to my students] you can choose. Would you choose to study hard and then find an easy job, or would you want to get a manual labour job just like you parents? … You know, our poor children … have to perform well. Because education is our only way out. (Teacher Ying)

Like migrant parents, teachers saw studying hard as the only conceivable way for migrant children to climb the social ladder, even though they knew only a token number of the migrant children would ever enter university and white-collar professions.Footnote 52 When the students failed in their schooling, the teachers mostly blamed them for their lack of effort or motivation, ignoring the subprime labour conditions that made it difficult for migrant parents to support their children's proper education.Footnote 53 Thus, the tenet of educational meritocracy was a perfect self-sustaining teleology, effectively impeding the formation of a truly critical understanding of class inequality.

Family and school are the two most important institutions in shaping children's social consciousness. The false class consciousness held by the migrant children did not develop in a vacuum but was deeply rooted in both the migrant families and the schools, as the above discussions attest.

Conclusions

The state of the class consciousness of working class children has received scant attention in current China studies. This study has examined the class consciousness of rural migrant children who are about to join their migrant parents and become “China's new workers.” It shows that children in upper grades of primary school have already formed important constructs on social class. Living on the margins – both geographically and socially – of Beijing, many of the rural migrant children in this study observed the suffering of their parents and neighbours and were sharp enough to identify “workers” and “bosses” as the essential parties in labour conflicts. Even at their young age, they had already developed a sober awareness of the distinction between manual and mental labour and quite firmly subscribed to the superiority of the latter. These findings suggest the existence of a burgeoning class consciousness in their young minds.

Rural migrant children also actively interpreted the adversities confronting their parents and fellow migrant workers, seeing educational failure as the main reason for workers falling into and being limited to physical labour. Moreover, the migrant children tended to attribute unjust employment relationships to the moral quality of individual bosses and workers’ bad luck. In short, education, morals and luck, rather than class structure per se, were considered to be the causes of workers’ misfortune. Such attribution features self-blame and passive acceptance of inequalities as fate, making it unlikely migrant children would mobilize or take collective actions to improve their future employment relations.

Indeed, many of the children rejected collective actions, instead hoping that education will change their destiny. Also, they saw workers as weak and dependent on their bosses’ mercy to improve their lives. As such, they expected their future bosses to be caring, open-minded and willing to listen to workers’ voices. Many admired the work and lifestyle of “bosses” and dreamt of becoming one in the future. As Freire said, there is a duality in the oppressed mind, as oppressed people simultaneously submit themselves to the oppressor, while internalizing the image of the oppressor as their role model.Footnote 54 This is indeed the case with the migrant children under study. Their interpretations of the class-based inequality showed false consciousness, overshadowed by individualism, meritocracy and the duality of images.

These views are not plucked from the air but rather are shaped by and emerge from the social milieu.Footnote 55 Educational meritocracy and prejudices against manual labour were strongly embraced by both the migrant families and the schools in this study. Nevertheless, labour issues were mostly left untouched in school, while the hukou discourse dominated school efforts to account for the injustices plaguing the migrant population. On those occasions when labour issues were discussed, teachers were ill-prepared to address them. Public school teachers try to remain “apolitical” while migrant school teachers, who rarely engage in collective actions to fight for their own labour rights, are unlikely to introduce to the children a critical reading of the labour issues.Footnote 56 It is evident that neither the children nor the adults and institutions surrounding them had enough exposure to conceptual resources to form critical views of class issues.

The false consciousness found among the migrant children in this study reflects the overall political climate in Chinese society. On the one hand, with the rising culture of individualization, structural inequalities tend to be reduced to differences in personal efforts and qualities.Footnote 57 On the other, despite unprecedentedly large numbers of “new workers” and increasing levels of class conflicts, the vocabulary of class has ironically been mutedFootnote 58 and replaced by differences in identity in the public media, educational institutions and even among the working class itself.Footnote 59 The identity politics of hukou is prominent in China's political culture and blocks people from seeing the deeper, more covert exploitation intrinsic to capitalist labour regimes. Migrant children's lack of critical consciousness results from the paucity of China's larger political culture. Thus, it is imperative to move beyond the identity politics of hukou and reinsert the class perspective into scholarship on rural migrant population in China.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments and suggestions. This research was partially funded by the Seed Fund for Basic Research from The University of Hong Kong (fund No. 201611159140).

Conflict of interest

None.

Biographical notes

Jiaxin CHEN is a research assistant professor at the School of Graduate Studies in Lingnan University, Hong Kong. Her primary field of research is sociology of education. She is particularly interested in research on migration studies, educational inequality and social reproduction, citizenship and critical pedagogy.

Dan WANG is an associate professor at the Faculty of Education in The University of Hong Kong. Her research focuses on educational inequality and social justice issues in China, with a special interest in the rural–urban divide, class reproduction and the work and professional development of teachers. Her current work explores the role of rural education in local community reconstruction and sustainable development.