Recent trends of globalization are marked by the rapid rise of countries from the Global South and the influences they project on to the international economic and political order established by the Global North.Footnote 1 Within such a context of shifting global power dynamics, the unprecedented growth of China–Africa cooperation attracts much discussion among policymakers, researchers and media agencies. Bourgeoning institutional reports, academic literature and news coverage have contributed both policy analyses of China's strategic agenda in AfricaFootnote 2 and field-based observations of the everyday activities of Chinese investors and migrants in specific African countries.Footnote 3 From ideological underpinnings to real-world practices, the China–Africa relationship is constantly understood as a distinctive module of international cooperation compared to the conventional North–South structure, one that is rhetorically based on principles of mutual respect, reciprocity and non-interference in each other's domestic affairsFootnote 4 and is characterized by pragmatism, flexibility and openness to negotiation.Footnote 5

Despite growing interest in China–Africa relations, Chinese overseas companies and their local strategies in specific African contexts remain under investigated. These companies are the meso-level agents of China–Africa cooperation and are connected to inter-state diplomacy on the one hand and day-to-day business activities on the other. They are the critical interface from which to examine the official construct of “Chinese exceptionalism”Footnote 6 and the real-world behaviour of concrete Chinese actors in Africa. Existing research, primarily drawing upon country-wide, multi-company surveys, has shed light on the overall patterns of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private companies in Africa.Footnote 7 They reveal the heterogeneous composition of Chinese companies and their varied investment agendas, operational logics and overseas capacities to organize production and workforces in different host African countries, which lead to contradictory impacts on local economic development and skills transfer.

While contributing important knowledge, two themes remain inadequately examined in the current literature. First, studies primarily focus on the role of the Chinese government in supporting the overseas ventures of domestic companies through diplomatic, financial and policy mechanisms, while largely neglecting how forces in the host country shape the local operations of Chinese overseas companies. Recent studies have interrogated the notion of Africans being merely passive recipients of Chinese investment by highlighting ways that state and non-state actors (pro)actively negotiate with and leverage support from Chinese and other foreign investors.Footnote 8 It is, therefore, imperative to critically assess the capacities and constraints of African agency in shaping the behaviour of Chinese overseas companies.

Second, while studies have identified the diversity of Chinese companies operating in Africa, there are insufficient analyses of the interrelationships among these companies in overseas ventures. These relationships, either cooperative, complementary, competitive or a combination of different forms, offer an important prism through which to examine the nature of Chinese investment in Africa. This approach entails viewing Chinese actors not as discrete entities doing business in an isolated manner and instead emphasizes a networked and relational perspective to examining how various actors support or undermine each other's overseas ventures and how their relationships align with or derail from the official commitment to China–Africa mutual development.

This article makes a modest effort to unpack these state–firm and firm–firm dynamics under China–Africa cooperation through a single company case study. The focus on one company allows for in-depth analysis of how specific firm characteristics (i.e. ownership status, institutional affiliation and internationalization trajectory) shape its overseas competitiveness, and how the host country exerts agency upon Chinese business actors and to what extent. The empirical research centres on a flagship Chinese company operating in the telecommunications sector of Ethiopia. Telecommunications, as a knowledge-intensive sector with a relatively high level of global competition, is seriously understudied in the China–Africa literature compared to industries such as manufacturing, construction and mining.Footnote 9 More importantly, the telecommunications sector in Ethiopia presents a unique case for research: unlike the liberal telecommunications markets in most African countries, Ethiopia's telecommunications sector is under tight state control,Footnote 10 allowing Chinese companies to dominate the local market by mobilizing relations between the Chinese and Ethiopian governments. The case company, to which I have given the pseudonym Huaxia Telecom in this article, is a Chinese parastatal that monopolized the Ethiopian market before it was surpassed by its Chinese rival – a private company introduced by the Ethiopian government. This local government-administered competition between two Chinese telecommunications companies led to a series of changes in the organizational structures and business strategies of Huaxia. By tracing the changes in Huaxia's operations in Ethiopia, this article explicates the interplay of local government intervention and inter-firm competition that shapes the local behaviour of Chinese companies in Africa.

In the remainder of the article, I start by reviewing two existing strands of theories commonly employed to understand the rise of national firms from East Asia – the developmental state (DS) and global production networks (GPN). I proceed by proposing a framework to integrate state agency and inter-firm dynamics to study Chinese overseas companies. I then briefly examine the development of China's telecommunications sector and the internationalization process of Chinese telecommunications firms using the case of Huaxia. I continue by elaborating on Huaxia's monopoly in Ethiopia and the subsequent local government strategies to contain its corporate power. The penultimate section traces the resultant changes in Huaxia's local operations. The last section concludes the article.

The Rise of National Firms from East Asia

The DS and GPN are two major conceptual frameworks used to understand the rise of national firms from East Asia. The DS theory accounts for the miraculous economic performance of East Asian capitalist economies such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore.Footnote 11 Central to the theory is a strong, development-oriented state, which, through effective industrial policies and a competent elite bureaucracy, governs the market and assists the growth of national firms so that they occupy important niches in the global economy. In the process, the state and firms develop a relationship based on “embedded autonomy,” indicating that the state forges close economic and social ties with domestic elites but also retains the independence and power to discipline the behaviour of capital.Footnote 12

However, the focus on state power to interpret the East Asian economic miracle has been challenged by shifting national and international conditions.Footnote 13 Domestically, increasing factionalism and internal rivalries within the national socio-political system undermine the state's institutional capacity. Internationally, as national firms mature and become more integrated into the global production system, they transcend the territorial and institutional confinement of nation-states.Footnote 14 Vertical disintegration and fragmentation of production relations at the global scale further leave the state with little room to manoeuvre.Footnote 15 Given these conditions, scholars argue that the DS theory, as a peculiar historical and geopolitical construct, provides a limited conceptual approach to understand the rise of globally competitive national firms from East Asia.Footnote 16

Partly in response to the shortcomings of the DS theory, the GPN framework has been adopted to understand East Asian development. It shifts analytical focus from a state-centric view to a firm-oriented explanation of the East Asian economic transformations in an era of accelerated globalization.Footnote 17 The GPN involves a vast network of economic actors and institutions led by a global lead firm from advanced industrialized economies.Footnote 18 Through its coordination, the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services are arranged in different places across the globe. Firms in East Asia, in an effort to be more competitive and integrative in the world economy, need to couple with the global lead firms and hence dis-embed themselves from the national state.Footnote 19 This process of “strategic coupling” is achieved through firm-specific strategies such as acquiring technological and managerial know-how to improve firms’ global competitiveness and cultivate good relationships with worldwide customers and partners.Footnote 20

The GPN framework presumes that well-developed national firms are capable of growing and prospering without being confined by the regulations and resources of the home state. As these firms mature and globalize, they replace the national government to lead the development of their respective industries.Footnote 21 However, while this observation may be the true for a number of highly globalized firms in Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan, it remains a problematic assumption in understanding the recent rise of national firms from mainland China. The Chinese state plays an indispensable role in the globalization of Chinese companies, especially those under state ownership. Despite decades of SOE reform, the Chinese government still retains tight control over companies in strategic and key industrial sectors by holding the majority stock share and appointing SOE cadres under the nomenklatura system.Footnote 22 With the government's “go out” strategy, scholars observe a strategic entanglement of the geopolitical and diplomatic interests of the Chinese state and the corporate and market motivations of Chinese companies.Footnote 23 Therefore, instead of decoupling from the state, the Chinese “national champions” heavily rely upon policy and financial support from the government and national banks in order to venture overseas.Footnote 24

However, despite the importance of the state in the globalization of Chinese companies, it is still debatable whether China falls into a typical DS paradigm. Proponents see China demonstrating a number of features of the DS such as the state prioritizing economic growth, performance-based cadre evaluation systems, central control over strategic sectors, and export-oriented industrial policies.Footnote 25 Opponents, however, argue that the predatory aspects of state practices, the prevalence of corruption and the entrenched disparity between central and local governments have resulted in a lack of internal cohesion or bureaucratic rationality for the Chinese state to orchestrate nationwide industrial transformation.Footnote 26 As a result, scholars characterize Chinese development as a “dysfunctional agglomeration of numerous local initiatives”Footnote 27 and the Chinese state as “polymorphous” with “contradictory features of developmentalism and predation, rivalry and unity, autonomy and clientelism, efficiency and inefficiency, across time and space.”Footnote 28 Niv Horesh and Kean Fan Lim further argue that the Chinese government reworks certain elements of Western neoliberalism, East Asian DS and Soviet state capitalism to create its own version of state-led development.Footnote 29

Horesh and Lim incisively state that the DS framework is neither a static model nor a simple fact; rather, analysis of the state should be grounded in the historical and geographical specificities of national development. Echoing scholars such as Linda Weiss,Footnote 30 Jim GlassmanFootnote 31 and Peter Dicken,Footnote 32 this article posits that globalization, rather than diminishing the role of the state, actually demands a stronger and more proactive state with a higher level of sophistication and capacity. Although there is no scholarly consensus on the nature of Chinese development, the government and its interventionist policies have played an important role in the country's domestic economic growth and global ventures.Footnote 33 I argue that the Chinese state is “polymorphous yet capable” in spearheading the country's international presence, while not necessarily retaining complete control over the actual performance of overseas Chinese actors in specific host country contexts.Footnote 34

The indispensable and distinctive roles of the Chinese government in firms’ globalization also underlines the need to seriously theorize the state into the conventional GPN framework. Recent scholarship has begun to centralize the state as an important conceptual and analytical factor in GPN theory.Footnote 35 Adrian Smith, drawing on Bob Jessop's strategic-relational approach, highlights the strategic coupling of interests between the EU and North African states to generate critical alliances in the pursuit of accumulation opportunities beyond state space.Footnote 36 Rory Horner identifies four roles played by the state in the GPN: as a facilitator of firms’ integration into the global economy, a regulator of economic activities, a producer via SOEs, and a buyer through large-scale public procurement.Footnote 37 In the case of China, Lim examines how the Chinese state, as a producer, forges new GPNs through mergers and joint ventures with multinationals in advanced economies.Footnote 38 His work interrogates the underlying assumption of strategic coupling that takes firms and the state as separate entities, i.e. firms are driven by private capital and profit motives while the state is in pursuit of public interests and political agendas. It also reverts the unidirectional and hierarchical North–South relationship in the GPN research to a South–North relation.

This article advances the ongoing efforts of integrating the state and GPNs in research by examining state–firm and firm–firm dynamics in a context of South–South cooperation. Specifically, drawing upon a flagship Chinese telecommunications company and its ventures in Ethiopia, this article makes two modest contributions. First, the case study not only sheds light on the ways that the Chinese state engages in the internationalization of Chinese companies and shapes their overseas operational capacity but also uncovers how the host government intervenes to contain the corporate power of foreign investors. By so doing, it moves away from the methodological nationalism of conventional DS research to the international dimension of state power.Footnote 39 Moreover, by contextualizing government strategies in the inter-state relations of China–Africa cooperation, it allows for a critical assessment of both the home and host state agency in shaping firm strategies. The case of Ethiopia is particularly illuminating given the country's endorsement of the DS model in its own national development.Footnote 40 In this context of close economic cooperation between two countries pursuing state-led development, it is imperative to examine how both states support and regulate Chinese overseas companies. The attention to the strategies used by the Ethiopian government also contributes to the recent scholarly call for reinserting African agency in research on China–Africa relations.Footnote 41

Second, while attending to both home and host government agency, the case study also forefronts the proactive and strategic activities of overseas companies in business operations. It shows that Chinese overseas companies are by no means the arms of the Chinese state but are capable of adjusting strategies in response to emerging circumstances in local and international contexts. In addition, different from the GPN's focus on the relationships between global lead firms in Western industrialized economies and the emerging national firms from East Asia, I examine the competition among Chinese companies operating in the developing world. With an understanding that Chinese overseas companies may engage in diverse relations, the focus on inter-firm competition specifically problematizes the widespread notion of Chinese companies being a coherent group of overseas players by revealing their internal dynamics and controversies. Given the predominant focus on the geopolitical aspects of China–Africa relations,Footnote 42 the firm-scale analysis also underlines the opportunities and challenges for the Chinese and host African governments in regulating the behaviour of firms in order to achieve mutual development goals, and contributes to the assessment of how the Chinese-led GPN in Africa influences local knowledge transfer, skills development and industrial transformation.Footnote 43

In summary, instead of assuming a zero-sum relationship between a singular-formed state and firms (i.e. the home state being a victim of the rise of national firms), I argue for critical investigations into the multifaceted relationships developed among home and host governments, as well as national firms with competing interests abroad. The rest of the article analyses the operations of one flagship Chinese telecommunications company in Africa. It takes an evolutionary perspective that views the firm's competitiveness as being built up in the past and continuing to develop through interactions with the government and other firms in the industry.

The Internationalization of Chinese Telecommunications Firms: The Case of Huaxia

Telecommunications is one of the fastest developing sectors in China. Between 1991 and 1999, telecommunications’ revenue grew by 2,050 per cent, reaching a turnover of 311.2 billion yuan in 1999.Footnote 44 Since entering the World Trade Organization in 2001, China has become a major global manufacturer of telecommunications equipment and provider of telecommunications services. In 2017, telecommunications accounted for 27.1 per cent of China's export of goods and 12.7 per cent of services.Footnote 45 The phenomenal growth of the sector is commonly attributed to numerous state initiatives to promote the transfer of foreign technologies and develop the competitiveness of local firms such as encouraging joint ventures, mandating the purchase of locally produced parts and equipment, and administering market competition to encourage in-house research and development activities.Footnote 46

As domestic companies mature, the Chinese government further provides financial incentives such as tax credits and soft loans to facilitate their globalization.Footnote 47 This financial support allows companies to adopt low-pricing strategies in the early years of their overseas ventures. A common globalization trajectory of Chinese telecommunications companies is to enter developing countries with price advantages and then expand to developed countries after establishing brand reputation.Footnote 48 In addition to financial support, telecommunications companies also benefit from close diplomatic ties between China and developing countries. Henry Wai-chung Yeung and Weidong Liu use the term “economic diplomacy” to describe the process of companies entering the markets of developing countries by undertaking Chinese government-funded projects.Footnote 49 Tokunbo Ojo identifies a triadic interdependent relationship between the Chinese government, developing country governments and Chinese companies, which is characterized by the entanglement of business interests and political relations.Footnote 50

The corporate history of Huaxia follows the overall growth trajectory of China's telecommunications sector. Founded as an SOE, Huaxia adopted a business model known as “state-owned and private-operating” in the midst of SOE reform. After being chosen by the State Council to be one of the 300 key SOEs in 1996, Huaxia began to export its products and services. So far, it has established partnerships with telecommunications service providers in more than 160 countries and regions and employs over 60,000 staff worldwide. Between 2004 and 2016, the accumulated revenue of Huaxia's overseas businesses reached 399.35 billion yuan, which accounted for nearly half of the company's total revenue (Figure 1a). Asia was a major foreign market, contributing an average of 46 per cent of the company's overseas revenue. Africa was a small but growing market, accounting for an average of 23.6 per cent of the overseas revenue. Yet, Africa contributed the highest gross profit margin – an average of 42.26 per cent during the period between 2004 and 2016, indicating that it is a highly lucrative market (Figure 1b).

Figure 1: (A) Operating Revenue and (B) Gross Profit Margin of Huaxia Telecom

Source:

Data obtained from the company website.

Given the importance of the African market to Huaxia, it is imperative to examine the company's entry strategies and local operations. Empirical research presented in this article draws upon the author's field research in the Ethiopian subsidiary of Huaxia between 2014 and 2017. Semi-structured interviews and informal conversations examining the company's local operations were conducted with 19 Chinese and 33 Ethiopian managers and employees. Participants were approached individually and randomly during the author's visits to the company.Footnote 51 Efforts were made to cover employees from different departments and at varied administrative levels. To cross-validate the information collected, all participants were asked the same set of questions. The data were then complemented by secondary information published on the company's website as well as the local and international news outlets.

Gaining and Losing the Monopoly in Ethiopia

Telecommunications is one of the least developed sectors in Ethiopia, lagging behind the regional average on multiple indexes.Footnote 52 The federal government controls the development of the sector through the only state-owned service provider, Ethio Telecom.Footnote 53 Reluctance to liberalize the sector has led to a retrieval of development assistance from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, pushing the Ethiopian government to seek alternative sources of capital.Footnote 54 Chinese telecommunications companies have, as a result, emerged as a major player in the Ethiopian market given their access to vendor financing from Chinese national banks.Footnote 55

Huaxia's monopoly in Ethiopia's telecommunications market began in 2006 during the third ministerial meeting of the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in Beijing. During the meeting, Huaxia and Ethio Telecom established a programme of cooperation, which granted Huaxia exclusive access to Ethiopia's national telecommunications projects, as set out in the Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty (PASDEP, 2005–2009). Funds were provided through vendor financing from the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (EXIM). With a total investment of US$1.9 billion, the PASDEP project was at the time the largest telecommunications contract undertaken by a Chinese company in Africa.Footnote 56 For a time, Ethiopia was Huaxia's “granary in Africa,” accounting for almost 50 per cent of the company's African revenue. As a project manager from Huaxia commented:

In 2008, [the Ethiopian subsidiary of] Huaxia made a lot of money and surprised the headquarters. Each project manager received an annual bonus of a few hundred thousand yuan. At that time, people in the headquarters were saying, “if you want to make money, go to Ethiopia.”Footnote 57

Huaxia and its monopolistic position in Ethiopia, however, soon attracted local and international criticisms about the quality of its products and services and its local business practices, especially the possible facilitation of the Ethiopian government's surveillance activities.Footnote 58 There were also growing concerns about the over dependency of Ethio Telecom on one Chinese company. With existing equipment being replaced by products from China, Ethio Telecom relied on Huaxia for spare parts, maintenance and the upgrading or expansion of services. The incompatibility of Chinese equipment with equipment from other countries gave Huaxia the opportunity to overcharge on subsequent projects.Footnote 59

In an effort to take back control of the sector, the Ethiopian government, through Ethio Telecom, deployed two major strategies. The first was to introduce a third-party overseer to manage its relationship with Huaxia and re-adjust the balance of power among the different parties. In 2009, Ethio Telecom called for international tenders from major global telecommunications operators. Sofrecom, a subsidiary of France Telecom, won the bid and signed a three-year contract to oversee Huaxia's operations as well as supervise Ethio Telecom's internal structural transformation and transfer managerial know-how to local managers.Footnote 60

The introduction of Sofrecom aimed to strengthen government control over the sector and impose rigorous business supervision on Huaxia. It signalled the government's awareness of the risks of working with one Chinese company on national telecommunications development. However, collaboration between Sofrecom and Ethio Telecom failed to achieve the anticipated goals. The French chief executive was replaced in the middle of his three-year term, and French managers were not allowed to make independent financial decisions. Ethio Telecom was later criticized by French managers for its preoccupation with a short-term, quantitative expansion of telecommunications networks rather than a careful consideration of operational costs and long-term network security. By the end of the contract in 2013, Ethiopian managers, mostly cadres from the government, took over the key positions in Ethio Telecom.Footnote 61 Despite the proactive move, Ethio Telecom's collaboration with Sofrecom did not prove to be an effective mechanism to either restrict Huaxia's monopoly or push for critical reform of Ethiopia's telecommunications sector.

A seemingly more successful move was the Ethiopian government's introduction of a competitor company to Ethiopia – Guoxin Telecom, a privately owned company from China and a major rival to Huaxia in both domestic and international markets.Footnote 62 In 2013, Ethio Telecom called for bids for a new round of national telecommunications development – the first Telecom Expansion Project (TEP I). According to a former director of Huaxia, the move stemmed from broken negotiations between Huaxia and Ethio Telecom: “When we negotiated the TEP I project with Ethio Telecom, they expected us to upgrade the existing 2 G system to 3 G for free. We calculated the costs and found it unprofitable, and so refused. We didn't expect that they would turn to Guoxin.”Footnote 63

Confident of its monopoly of the local market, Huaxia refused to compromise on contract terms without knowing that Ethio Telecom was already in touch with Guoxin's leadership. Huaxia's managers were convinced that it was not economically viable for Ethio Telecom to shift to another partner and only realized later that “they [the leaders of Ethio Telecom] were more politically determined than economically minded.”Footnote 64

The public tender for the TEP I project ended with Huaxia and Guoxin sharing the US$1.6 billion contract, with vendor financing from the CDB and EXIM. As the TEP I moved to implementation stage, Guoxin quickly proved itself to be a ruthless breaker of Huaxia's local monopoly:

When negotiations [for TEP I] started, we took over 80 per cent of the contract, which later was reduced to 70, then 60, and now only 20 per cent. Guoxin took Addis and the northern part of the country, a total of four regions. We originally had six regions in the south and the west. Then Eriksson came in and took over four of our regions. But it later lost two of its regions to Guoxin.Footnote 65

The Swedish telecommunications company Ericsson was included in the TEP I one year after Huaxia and Guoxin signed the contract. It took over a portion of the project that was originally contracted to Huaxia. Although this was a move to further constrain Huaxia's business in Ethiopia, Ericsson did not perform in the way expected by Ethio Telecom:

Ericsson had a poor reputation [among Ethiopian officials] as it refused to do any construction work for Ethio Telecom. You know, we must do everything – groundwork, towers, line systems, flooring, etc., not just the telecoms part. The Ericsson folks refused and said they were only here for telecoms equipment and system installation.Footnote 66

Unlike Ericsson, Guoxin “was determined to lose US$100 million in order to enter Ethiopia,” according to a former marketing manager. Since its entry, Guoxin has engaged in cut-throat competition with Huaxia over local projects, finance and human resources:

Guoxin gave a lot of equipment [to Ethio Telecom] for free at first, but it later charged very high maintenance fees … It lured our local employees by offering salaries that were 2–3 times higher than ours and promised a bonus of a few thousand Ethiopian birr if anyone could persuade his or her colleagues to jump to Guoxin. It [Guoxin] did that just to cause damage in our daily operations.Footnote 67

Firm Responses: Changes in Local Operations

With deliberate host government intervention and the successful entry of Guoxin into the market, Huaxia lost a large portion of the TEP I project by 2016. This fierce competition, in part, triggered a series of changes in the company's local operations in terms of internal organization and business strategies. Numerous efforts were made to streamline the company's management structure, enhance employees’ loyalty, diversify business portfolio, increase political capital and improve local reputations.

Changes in firm organization

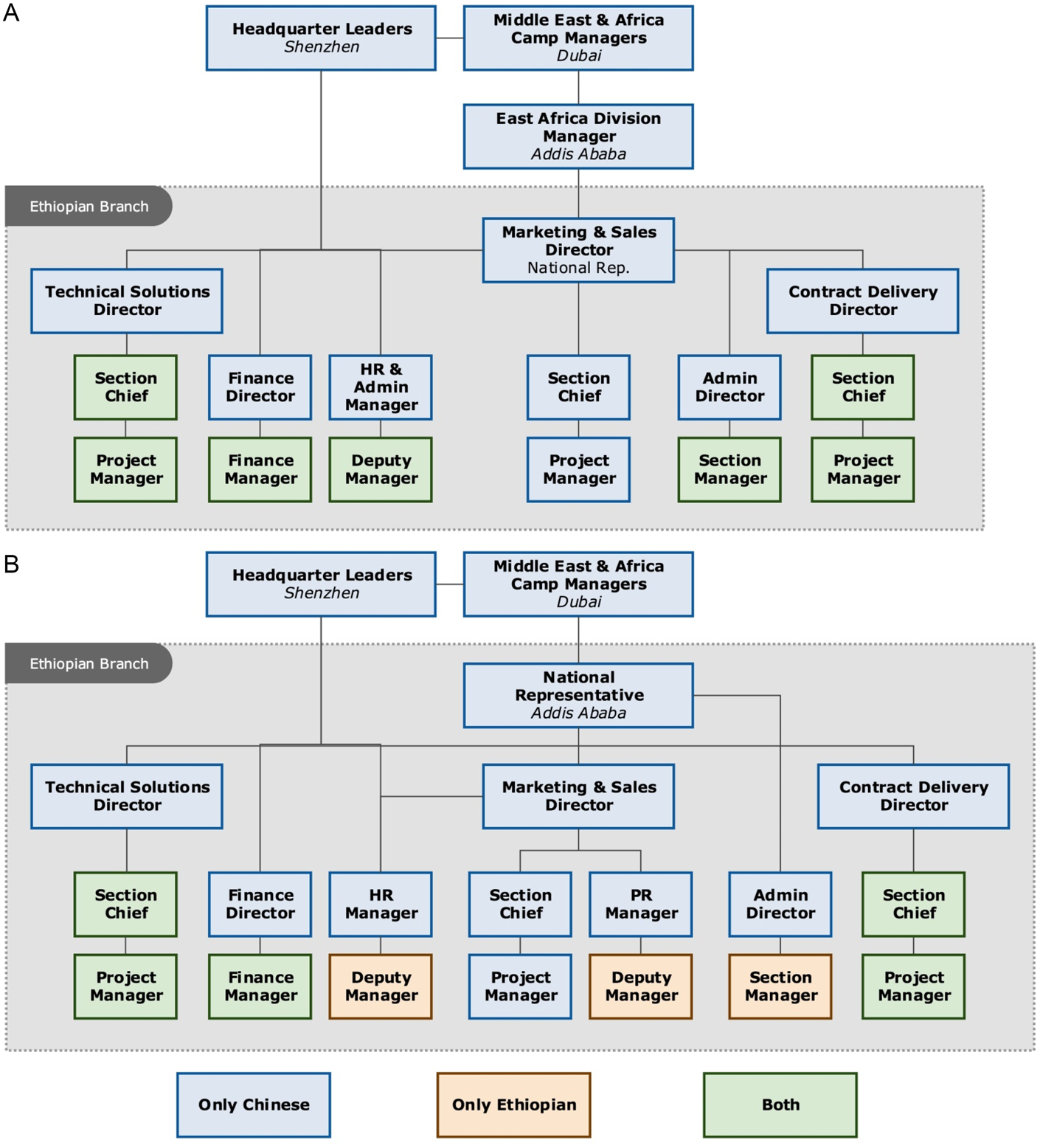

Huaxia maintains a complex organizational hierarchy that includes five levels of management. Below the top-tier management in the headquarters, there are managers at the regional, sub-regional, national and project levels. Before 2017, the Ethiopian subsidiary was under the East Africa Division, which was part of the Middle East and Africa Camp (Figure 2a). As the head of the East Africa Division, it supervised subsidiaries in Eritrea, Djibouti, Sudan, South Sudan and Uganda.

Figure 2: Management Structure of Huaxia (a) before and (b) after 2017

In the Ethiopian subsidiary, top-level management used to include an East Africa Division manager, who was a third-level manager within the entire company, and three directors who supervised three core departments of Marketing and Sales (MS), Technical Solutions (TS), and Contract Delivery (CD).Footnote 68 While these three directors were considered to be fourth-level managers, the MS director had conventionally been a half-rank higher owing to his dual post as the national representative of Huaxia in Ethiopia.

The Ethiopian subsidiary's under performance following Guoxin's entry into the sector led to a change in this managerial structure in 2017.Footnote 69 The East Africa Division was removed, leaving the Ethiopian subsidiary under the direct supervision of the Middle East and Africa Camp (Figure 2b). This change was intended to simplify bureaucratic procedures in the company and strengthen the headquarters’ control over overseas subsidiaries. The national representative position was then shifted from the MS director to the former division manager. This was seen, among the managers in Huaxia, as a transition to a smaller managerial class in the near future. Meanwhile, a Public Relations (PR) section was established under the MS department to handle the subsidiary's local relations.

In addition to changes in the management structure, the size of the workforce was reduced from 200 Chinese and 150 locals in 2014 to 120 Chinese and 100 locals in 2016. Following the loss of a major portion of the TEP I, Huaxia closed its sub-regional offices across Ethiopia, leaving just one in western Oromia, with 15–20 employees to handle its ongoing projects.

Together with downsizing its workforce, an effort was made to promote localization, i.e. replace Chinese expatriates with local Ethiopians. This was considered as a way to save expatriation costs and promote local employees’ loyalty to the company so as to prevent them from moving to Guoxin. Under the localization initiative, certain positions in the subsidiary were given over to local employees, some of whom were promoted to managers (Figure 2b). Especially within the human resources, finance and administration departments, positions that used to be filled by both expatriate and local employees were all transferred to Ethiopians.

Central to this localization was a “key staff motivation” programme, under which 25 seed local employees were selected as future leaders of the company. Each of the 25 employees received individualized professional development plans, salary increase guarantees and extra training provisions as well as opportunities to work on different projects. The 25 slots were updated on a quarterly basis according to work performance and supervisor evaluations. In this way, the company intended to incentivize every local employee to compete for the slots.

To further increase local employees’ sense of belonging, Huaxia also organized a number of company-wide social events such as Ethiopian New Year celebrations, sports games and other informal gatherings. With these various moves, Huaxia sought to distinguish itself from Guoxin's company culture, which values aggressive, competitive and predatory relations among employees and with its competitors. In contrast, Huaxia emphasizes a culture of perseverance, diligence and determination, which implies the development of a flexible, humane and respectful working environment and management–employee relationship.

Changes in business strategies

In Ethiopia, Ethio Telecom had been Huaxia's most important client, accounting for more than 80 per cent of the company's local business. However, with Guoxin aggressively taking over a major portion of the TEP I and outcompeting Huaxia on other public projects, winning bids and getting contracts became the top priority for Huaxia. Consequently, the MS department enjoyed an elevated status within the company. Employees in this department had substantial authority to mobilize company-wide resources for bidding purposes. Daily work in the department was considered top secret and the loss of bids could lead to the replacement of section chiefs or a heavy cut in annual bonuses. The competition between Huaxia and Guoxin became so fierce that employees from the two companies barely talked to each other even at social events organized by the Ethiopian government or the Chinese embassy. Both companies valued their respective competitive intelligence and offered special rewards to employees who managed to get their rival's bidding and contract information.

Meanwhile, Huaxia also actively sought out other contract opportunities to sustain its local business. One important source was gaining subcontracts from other Chinese companies. For example, China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation won a few economic zone construction projects across Ethiopia and subcontracted the internet development component to Huaxia. Huaxia also built the communications signal system for the Addis–Djibouti Railway under a subcontract agreement with the China Railway Engineering Corporation. Taking on subcontracts differentiated Huaxia from other major SOEs who, in most cases, only worked as main contractors. Nonetheless, acting as both a contractor and a subcontractor enhanced Huaxia's operational flexibility.

Although being an SOE did not protect Huaxia from inter-firm competition, it did give it access to subcontracts from other Chinese SOEs. To further build its connections with other Chinese companies in Ethiopia, the company served as the vice-chair of the local Chinese Business Association. It assisted in the organization of networking events and knowledge-exchange sessions among Chinese companies, hosted official visits by Chinese government or business delegations, and helped officials in the Chinese embassy to handle local affairs with regards to Chinese companies and citizens.

In the newly established PR department, a Chinese manager was responsible for socializing with local Chinese officials from the embassy and the Chinese Mission to the African Union, as well as other major SOEs and private companies. Developing congenial relationships with members of the local Chinese business and political community allowed Huaxia to collect critical information on potential projects, forge timely collaborations and increase its leverage when negotiating with Ethiopian officials:

We need to make Chinese officials happy and maintain good relationships with other Chinese companies. Such relationships can help us win small projects, even if they are much smaller than the TEP.Footnote 70

When we plan a launch event for a new terminal product, we invite the Chinese ambassador or the economic and commercial counsellor. As long as he agrees, we are more likely to invite an Ethiopian official of a similar or higher rank.Footnote 71

In addition to building local business and political connections, Huaxia also put forth efforts to improve its social reputation through various corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities. It engaged in activities such as training community officials, sponsoring local events and donating telecommunications equipment to schools. The Chinese PR manager would select activities that “have the widest media and community influence.”Footnote 72 Meanwhile, an Ethiopian PR manager was appointed in 2016 to handle local media relations. He regularly communicated with a group of local and international media outlets to ensure the timely publication of reports on the company's progress with projects, charity work and other social activities.

Discussion and Conclusion

The global ventures of Chinese companies necessitate the development of a new, integrated framework in order to conceptualize the state–firm and firm–firm dynamics in the process. The existing DS and GPN theories, which take either a pro-state or pro-firm perspective, fail to acknowledge the intertwined forces of state agency and firms’ proactivity in shaping Chinese companies’ local operations in the developing world. Drawing upon an empirical case study of one flagship Chinese telecommunications company in Africa, this article posits that globalization should not entail the demise of the state as a powerful agent of firms’ global ventures, especially in places like China where state-led development remains the central political and economic reality. Rather, it necessitates a move away from nationalist accounts of state agency to understanding new configurations of state power at transnational geographical scales.Footnote 73 As the case study reveals, Chinese overseas companies, especially those affiliated with the Chinese government, are by no means disconnected from their home base. Despite being “national champions,” these companies are yet to fully articulate their global economic positions to trump the state. Instead, they rely on the economic diplomacy forged between China and other developing countries when establishing themselves in overseas markets.

While the Chinese state performs the roles of both a facilitator and a producer in developing Chinese company-led GPNs in Africa, once abroad, the host government actively works as a regulator of foreign investment activities and an enforcer of rules and laws.Footnote 74 Especially in Ethiopia, the federal government retains a massive presence in the national economy and tightly controls its strategic industries and key national projects. In the case discussed in this article, rather than being deprived of agency, the Ethiopian government took active measures to contain corporate power by introducing a third-party regulator and inviting another Chinese company to increase its leverage in contract negotiations. The introduction of Guoxin to the domestic market, according to Huaxia's manager, indicates that decision making in Ethio Telecom is not merely driven by economic rationality. Rather, the government officials were willing to sacrifice short-term economic interests in order to break Huaxia's monopoly of the sector.

In addition to active state roles, inter-firm dynamics in the case study highlight the diverse relationships forged among national leading companies from the same home country. These multifaceted relationships interrogate the notion of Chinese companies being homogenous, coherent, state-driven entities engaging in mutually beneficial operations abroad. The inter-firm competition, fostered by the host government, pushed Huaxia to undertake a number of organizational and business changes. Specifically, Huaxia streamlined its management hierarchy to improve administrative procedures, diversified its local businesses by taking on subcontracts, increased its local political and social capital through various PR and CSR activities, and promoted workforce localization in order to build a more cohesive workplace.

However, despite various promising changes, it remains unclear whether the Ethiopian government has the capacity and determination to continue managing inter-firm competition for the sustainable development of its telecommunications sector and the improvement of local skills. The telecommunications industry in China benefited from effective government intervention; yet in Ethiopia, such state control over national projects is yet to translate into improved local capacity or industrial transformation at large. From infrastructure construction to software development, the Ethiopian client prefers a wholesale operation by Chinese companies, rather than empowering local firms to build economic linkages.

Moreover, inter-firm competition can also have contradictory impacts on local employees. On the one hand, cut-throat competition may push Chinese companies to minimize costs by cutting salaries, dismissing employees and increasing workloads, all of which will transfer the business pressure down to individual employees. On the other hand, increased competition may improve workers’ job mobility as they become more valuable in the labour market. In the latter case, inter-firm competition can enhance employees’ positionality in production relations with the Chinese management. Future studies are therefore necessary to continue monitoring the development of the telecommunications sector and evaluate the local behaviour of Chinese companies to assess whether Chinese investment in Ethiopia is truly generating a mutually beneficial outcome as claimed by the government officials on both sides.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Professor Abdi I. Samatar and two anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier drafts of the paper. The usual disclaimer applies.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical note

Ding FEI is a development and economic geographer with research interests in the relationship between state, capital and human agency in the uneven process of China's globalization and its implications for industrial transformation and local capacity building in the Global South. Fei's empirical research examines the variegated construction of local work regimes by globalized Chinese state and private capital in Ethiopia, and she conducts case studies on Chinese companies engaging in multiple sectors of overseas investment.