Current anti-Chinese sentiment, especially in the United States, has been constructed based on a knowledge-production background consisting of two components: the material fact of China's rising power (which triggers a sense of fear regarding the replacement of an established order), and ideational factors based on how the rising China phenomenon is interpreted. The second component stems from at least two groups of analysts. The first analyses China using established Western IR theories that emphasize threats to and opportunities for the current international system. Accordingly, some Western observers use terms such as “Beijing consensus,”Footnote 1 “rise of the Middle Kingdom,”Footnote 2 and the “new centre of gravity”Footnote 3 when comparing Chinese and Western governance models. Despite the obvious international benefits of China's rise, sceptics continue to speculate on Beijing's plans to “pierce,” “penetrate” or “perforate” existing democracies,Footnote 4 or to establish a Sino-centric regional order based on yet-to-be-determined governance norms and rules.Footnote 5 Beijing's self-described pacifist leanings under Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 and “harmonious” discourses promoted by Chinese IR scholars exerted some persuasive power for a short while, but President Xi Jinping's 习近平 increasingly assertive foreign policy actions and oppressive domestic governance practices are prompting new perceptions of a China threat.

The second group of analysts expresses greater sympathy for China in its dealings with Western responses to China's nation-state building efforts. Members of this group are more likely to describe China's rise as an opportunity for establishing strategic alliances with other non-Western actors for purposes of challenging current Western-centred discourses. There are many examples of this standpoint, one of the most famous being Stanley Hoffmann's query concerning the centre of IR studies.Footnote 6 Two decades later, contributors to the edited volume International Relations: Still an American Social Science? called for greater multiplicity in the discipline.Footnote 7 In 2002, the British IR scholar Steve Smith strongly criticized the ways in which North American-centred IR had become the mainstream discourse, thereby inhibiting attempts to understand other cultures and nationalities.Footnote 8 In a 2007 special issue of the Journal of International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, Amitav Acharya and Barry Buzan were among contributors bemoaning the absence of non-Western IR theories.Footnote 9 In the past two decades, there has been a growing number of challenges to Western IR dominance and new efforts to establish what is now commonly referred to as “post-Western IR theory.”Footnote 10 While some members of the second group have attempted to understand China from the perspective of Chinese intellectuals, others have created categories such as “non-Western” that initiate additional ontological spaces for conflicting Chinese and Western IR discourses. Still others have created Chinese IR discourses that only reinforce existing beliefs about the expected actions of nation-states and authoritarian regimes – that is, the pursuit of national interests and one-party systems.Footnote 11

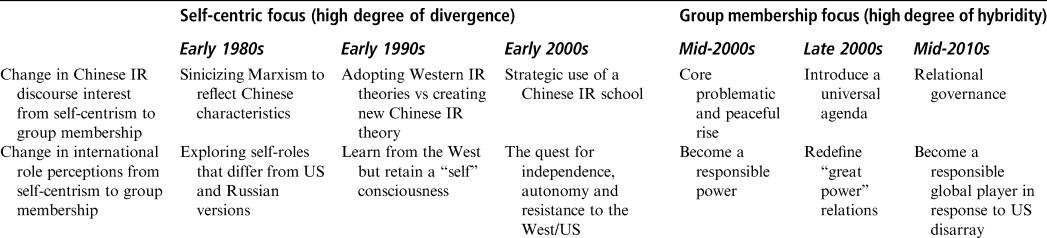

The two groups mostly view China as a rational actor with clear goals involving replacement of the current dominant power, making up for historical interventions by Western powers, and the general pursuit of national interests. According to these goals, Chinese IR scholarship reflects strong political and nationalist motivations to guide Chinese foreign policy through post-Cold War uncertainties,Footnote 12 with national survival and self-interests serving as the most important priorities.Footnote 13 However, there is potential for an alternative approach to understanding Chinese IR scholarship and China's rise as a relational, process-oriented epistemology,Footnote 14 one that simultaneously fulfils self-centric and group membership needs and reflects changes in self-role perceptions (Table 1).Footnote 15 In this context, relationality refers to the motivations and tendencies of Chinese scholars to link the IR discipline and its representations of China with those expressed by Western great powers. The shared purpose is to establish dual collective and hybrid ontologies that balance China's needs for self-centrism and inclusion. Examples are found in Chinese efforts to encourage greater-self and collectivist values.Footnote 16

Table 1: A Comparison of Changes in Chinese IR Discourses with Changes in China's Self-perceived International Role

Understanding how Chinese IR scholarship is using an alternative epistemology to represent China's rise is academically important for its potential contributions to global IR knowledge production. However, there is a tendency to rely on established concepts and conventional views about world order without offering alternative interpretations of power politics and China's rise.Footnote 17 Therefore, this paper is aimed at both understanding the multiple dimensions of China's rise and assessing our openness to alternative assumptions. I will discuss changes in Chinese IR discourse and parallel perceptions of China's international role over the past three decades. In so doing, I reveal a move away from self-centrism and towards relational network construction.

Creating Hybrid IR Discourses

When reviewing the processes underlying post-Cold War Chinese IR theory construction, one finds characteristics such as a sinicization of Marxist doctrine to resolve cultural inconsistencies; an IR school construct motivated by national identity; restraint in antagonistic, exploitative and rebellious language; and an idealist worldview. Changes in these characteristics do not necessarily indicate mercuriality or inconsistency as a trait of Chinese IR scholarship, but rather underscore an effort on the part of its practitioners to establish and maintain balanced relationships between self-centric and group membership needs. There are many examples of how China is trying to restore national pride by aggressively defending every inch of historically claimed territory, while concomitantly promoting a pacifist self-image meant to counter Western portrayals of China as an economic, political and military threat.Footnote 18 Since the primary motivation is not assimilation into the established world order but co-existence in a shared ontological space, the hybrid nature of Chinese IR scholarship is a useful starting point for discussing the composition of post-Western (rather than non-Western) IR, as well as Beijing's increasingly confrontational stances.

Initial efforts to create a Chinese IR discourse can be traced to the 12th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), during which Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 called for the development of “socialism with Chinese characteristics”:

In carrying out our modernization programme, we must proceed from Chinese realities. Both in revolution and in construction we should also learn from foreign countries and draw on their experience, but mechanical application of foreign experience and copying of foreign models will get us nowhere … We must integrate the universal truth of Marxism with the concrete realities of China, blaze a path of our own and build a socialism with Chinese characteristics – that is the basic conclusion we have reached after reviewing our long history.Footnote 19

Originally a domestic political slogan, “socialism with Chinese characteristics” encouraged scholarly reflections on how China could reconnect with socialist doctrine in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution. As part of its 1980s research agenda, the Party encouraged Chinese IR scholars to reconsider China's distinct features and to carefully review potential Chinese IR boundaries, concepts and goals for the purposes of establishing an operational foreign policy orientation based on a supportive mix of socialist values and Chinese realities.Footnote 20

China's understanding of international relations has long been dominated by political leaders wanting to promote a Marxist economic worldview; it was not until the 1987 Shanghai Seminar that Chinese scholars were encouraged to create new theory for policymaking and analysis. Previously, “Chinese characteristics” referred to a mix of Marxist-Leninist orientation, traditional Chinese cultural values and “New China” diplomatic practices. Coming at the end of the Cultural Revolution and a period of strict Party control, Chinese scholars naturally seized every opportunity to analyse China's relations with other actors, with the identification of IR patterns taking a back seat to addressing China's emerging role in world affairs and presenting the best possible image to an international community that seemed willing to accept its participation.

In an early attempt to create Chinese IR theory, Wang Jianwei, Lin Zhimin and Zhao Yuliang reconsidered Marxism-Leninism to test its potential use as a non-doctrinal tool for studying international politics.Footnote 21 Rather than challenge Western IR assumptions or concepts, they were more interested in using Marxist-Leninist theory to understand an evolving world while promoting the “four modernizations” economic development policy.Footnote 22 It was not until the Shanghai Seminar that they could openly discuss two topics of primary concern: identifying China's needs for the coming age and the utility of Marxism-Leninism for “correctly” (zhengquedi 正确地) dealing with new contexts. The idea that Marxism-Leninism would lose its strength while China made new world connections is a rational and functional way of approaching Chinese IR scholarship. However, from a relationality perspective, utility is the last concern of Marxist-Leninist theory. The first Chinese IR scholars viewed their most important task as retaining and clarifying Marxist doctrine while dealing with economics, war and peace, and other dominant topics.Footnote 23 In other words, making the necessary adjustments and arguments to ensure a central position for Marxism.

Adopting Western IR while Retaining a Consciousness of Self

Chinese scholars continued to debate the wisdom of creating their own IR theory in the early 1990s – a period marked by the wholesale importation of US IR concepts. At a 1994 national meeting on “Building an IR theory with Chinese characteristics,” Zhu Liang described it as complementing Deng Xiaoping's “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” Lu Yi emphasized the contributions of Marxism and Deng's ideas to Chinese IR theory construction, and Liang Shoude used Zhu and Lu's views regarding the roles of socialism and Marxism to make his case for an indigenous Chinese theory.Footnote 24 According to Liang, any emphasis on Chinese characteristics must acknowledge international differences, pluralism and China's development. He also argued that any Chinese IR theory must support the Party's domestic modernization policies, the country's national interests and Chinese autonomy.

Liang used the term zijue 自觉, referring to a China that is conscious of its specific needs and contexts, when encouraging his colleagues to consider Chinese IR theory content. When arguing that his peers could achieve self-confidence as long as they maintained zijue, he also described a need to correctly understand China's parallel statuses as a developing country, a political great power and a socialist great power, with all three emphasizing independence, autonomy and peace.Footnote 25 In hindsight, Liang was reminding his colleagues that regardless of the final form of IR theory with Chinese characteristics, they had a responsibility to correctly represent China's own needs – that is, to ensure that socialist political correctness took precedence over efforts to identify scientific truths.

Although the 1994 meeting failed to produce a consensus, it allowed attendees to identify requirements such as emphasizing Chinese culture but using universal language when describing historical conditions. Thus, in his 1995 book on contemporary international politics, Wang Yizhou encouraged Chinese scholars to “borrow” concepts and methods from other parts of the world to soften the effects of ideology.Footnote 26 In contrast to Liang Shoude's strategy, Wang Yizhou and Su Changhe and Peng Zhaocang discussed specific conditions for any Chinese IR school that might emerge, emphasizing patience in light of the inevitability of China having its own IR theory.Footnote 27 Patience was also associated with a perceived need for political correctness regarding Chinese expectations for its great power status, while still leaving the door open for hybridity.

Initial Formation of a Chinese IR School

The early 2000s witnessed an effort to replace Deng's “Chinese characteristics” with the more academic-sounding “Chinese school” – a change motivated by political correctness and a desire to emphasize independence and autonomy. The change also denoted a perceived need to connect with the English School to block American hegemonism, reflecting beliefs among some Chinese scholars that the English School's IR discourse could be used in support of China-specific knowledge and that their goals were unachievable if China's relations with Western countries (especially the US) continued to be based on unequal exchanges.Footnote 28 Chinese officials never missed an opportunity to remind others of their history of unfair relations going back to the late Qing dynasty.Footnote 29

Two articles published in the early 2000s mark the first official use of “Chinese school” as a replacement for “Chinese characteristics.” Mei Ran and Ren Xiao both cite US dominance in international political scholarship when arguing that the “Chinese school” has fewer ideological connotations.Footnote 30 In Mei's view, since the US approach emphasizes strength and power, a Chinese-style approach should emphasize the needs of victims.Footnote 31 In contrast, Ren Xiao's call for a “Chinese school” emphasizes Chinese–US cultural parity.Footnote 32 According to Ren, the problem of US dominance in IR theory and research is owing to the US belief in Enlightenment-derived monism and its tendency to describe its own systems, institutions and values as universal. He cites the pluralist views of British philosopher Isaiah Berlin when discussing the dangers of this tendency and encourages theoretical analyses addressing the potential for cultural co-existence. In Ren's opinion, Chinese culture emphasizes harmony while Western culture emphasizes power, Chinese culture promotes a middle way while Western culture views things as black or white, and Chinese culture looks for common ground as opposed to Western confrontational tendencies. Note his use of a Chinese-versus-Western duality when discussing the perceived Western habit of black-and-white reductions.

The next call for connection with the West emerged in the mid-2000s, with some Chinese scholars discussing a Chinese IR school in the context of a “core problematic” (hexin wenti 核心问题) based on three assumptions: a distinct approach to analysing international politics based on a Chinese worldview, a potential for learning from the English School's success in a US-dominated field, and inspiration from China's peaceful integration into international society since the 1980s.Footnote 33 Based on his interpretation of this core problematic, Qin Yaqing assumes that when China becomes a great power it will develop an IR theory that meets its specific needs.Footnote 34 Noting the US IR theoretical focus on that country's post-Second World War hegemonic status versus the English School's emphasis on creating an international society in response to the UK's declining hegemonic status, Qin believes that peaceful integration into international society will be the core problematic of any Chinese IR school that emerges.Footnote 35 Qin's main point is that China can follow the same path as previous great powers in identifying and pursuing core concerns while formulating a discourse of peaceful integration into international society.

A review of the Chinese IR literature reveals an idealist view of international society, with China's peaceful rise tied to its changing identity and integration into existing institutions. According to Zhang Xiaoming (an English School supporter), the primary characteristics of China's rise are material power and acknowledgement of its great power status.Footnote 36 One of his biggest concerns is “whether the attitude of [a] rising China should be to become accustomed to, accept, revise, or challenge [Western-established] norms, or include all possible choices” – an integrationist perspective based on the English School's contextualization of China's rising power as part of a Euro-centred international society in which identity, norms and institutions are key concepts for understanding Chinese relations with other actors.Footnote 37 Accordingly, China must acknowledge the presence of a Euro-derived international society, with its own core values and norms, rather than “standards of civilization” that all countries must abide by. Zhang thus believes that China should continue to participate in international society, accept greater responsibility and learn how to react to and accommodate changes in international norms. Zhang might be considered an optimist in that he does not perceive inevitable cultural conflicts between China and a Euro-centric international society but asserts that China would be wise to accept human rights and democratic values with the idea that it can eventually influence reforms – that is, pursue a strategy based on accommodation and revision.

Universal Agendas and a Call for Relational Governance

In the late 2000s, Chinese scholars started experimenting with a universal agenda – an effort reflecting China's expanding self-confidence about its international roles and responsibilities. Two discourses emerged, the first based on tianxia 天下 (“all under heaven”). In addition to being the focus of philosopher Zhao Tingyang,Footnote 38 this centuries-old idea is at the centre of vigorous debate within a group of IR scholars that includes Qin Yaqing,Footnote 39 Xu JianxinFootnote 40 and Zhang Feng.Footnote 41 Zhao's version of tianxia extends beyond current state-centric IR thinking. In his comparison of Chinese and Western worldviews, Zhao asserts that “Chinese political philosophy defines a political order in which the world is primary, whereas the nation/state is primary in Western philosophy.”Footnote 42 Zhao says his intent is not to emphasize ontological or other fundamental differences between China and the West, nor to enhance China's identity in opposition to Western thought. Instead, his motivation is to use the history of Chinese political institutions to create a system corresponding to Kant's “perpetual peace” or the Chinese concept of “universal harmony.” Zhao's tianxia argument also addresses issues regarding co-existence between China and other nation-states resulting from an overemphasis on state sovereignty.

Yan Xuetong and his IR realist peers at Tsinghua University are behind the second discourse, which envisions a self-described “benign power” replacing a corrupt power as a global leader.Footnote 43 To apply modern state logic to China, Yan and his colleagues are searching for evidence of power politics (favoured by Western IR realists) in China's dynastic history.Footnote 44 For Yan, military and diplomatic strategies should not be motivated by power or security concerns but by China's return to centre stage in international affairs, with the former eventually sacrificed for the latter.Footnote 45 Note that Yan's approach is informed by his effort to establish a link between Chinese legalism and a universal global order.Footnote 46 For example, in an article on “moral realism” (daoyi xianshi zhuyi 道义现实主义), he addresses what he views as a misinterpretation of Hans Morgenthau's realist views.Footnote 47 Arguing that Morgenthau never denies a function for morality in international politics but emphasizes a proper evaluation of its role, Yan sees similarities between Morgenthau's ideas and Chinese cultural views. Accordingly, Yan sees an opportunity to generalize Chinese morality to Western assumptions rather than vice versa. His legalist-based argument in defence of a “humane authority” represents a potential link between Chinese cultural perspectives and Western IR theory that supports a Chinese interpretation of international peace and harmony.

During a period marked by Xi Jinping's support for participation in established multilateral institutions and the Belt and Road Initiative – a project described as emphasizing connectivity and a shared international destiny – Chinese IR scholars are calling for associations that emphasize a relational governance research agenda. In one of several articles published in one of China's top political science journals, World Economics and Politics, Qin Yaqing lists three IR assumptions for a relational theory of international politics: a world order built on relations, the unification of knowledge and practice, and zhongyong 中庸 (“middle-way”) dialectics.Footnote 48 In another, Su Changhe uses cultural and diplomatic examples to argue that the Chinese idea of “comprehensive understanding” is indispensable to relational theory and that relational concepts could replace rational concepts as a foundation for understanding international politics.Footnote 49

The Chinese relational governance vision entails moving beyond a preoccupation with nation-states as rational actors with self-subjectivities and multilateral relational objectives. Informed by Confucianism, this vision advocates a social greater-self involving actors who always consider the interests of others – that is, bilaterally based relationality within a multilateral framework.Footnote 50 This framework starts with the assumption that other countries will act according to both self-interests and the interests of their negotiating parties when addressing greater-self concerns. China's behaviour and expectations are subject to identical limitations for the same reasons, with relational concerns serving as reference points for judging content in terms of political correctness.

Conclusion

From a rationality perspective, Chinese IR scholarship serves as an example of how countries and cultures outside North America and Europe can resist long-dominant imperialist discourses. In contrast, there is a growing trend among Chinese IR scholars to reconnect with the outside world, with their perceptions of others driven not by divisions in terms of what nation-states are expected to do but by maintaining bilateral or multilateral relations according to an imagined shared ontology in which no actor is transformed according to the universal claims of others. As it evolves, Chinese IR scholarship is likely to contain a considerable degree of hybridity involving the synthesis of Marxist, Chinese traditionalist and Western ideas in terms of group membership, with local preferences based on China's perceptions of practical but politically correct self-centric needs. Table 1 presents the results of self-centric/group membership requirements by which Chinese IR discourses have evolved, with perceptions of China's international role serving as a starting point for assessing hybridity and divergence. Recent calls from Chinese IR scholars for a relational IR appear to be gaining strength, with subjectivity stepping aside in favour of a collectivist greater-self based on shared or identical responsibilities. The main question regarding this process is how Chinese IR scholarship might evolve should real politics and state sovereignty concerns emerge as the primary drivers of national rejuvenation – in other words, the potential effects of political correctness on relationality.

Acknowledgements

This research was, in part, supported by the Ministry of Education, Taiwan, ROC, and the Aim for the Top University Project to the National Cheng Kung University (NCKU).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical note

Hung-jen WANG is associate professor in the department of political science, National Cheng-Kung University, Taiwan (ROC). His research interests include non-Western IR theories, Chinese foreign policy and international security.