If there's already a scenic park, the local government will build a temple inside the park; if there's already a temple, it will build a scenic park around the temple; and if there's nothing, the local government will build a temple and then a scenic park around it.Footnote 1

Senior monk, Temple DragonThe temple needed this money at the beginning. Now we have accumulated some assets and no longer depend on the entrance fee as a major source of income. We discussed this with the local government and just two months ago we cancelled both admissions: 10 yuan for the temple and 50 yuan for the scenic park.Footnote 2

Abbot, Temple WestControlling religion has been a major task for the Chinese state.Footnote 3 The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has devoted major resources to this project, as manifested by the political co-optation of religious groups in its united-front work policy and the campaigns to eradicate religion altogether during the Cultural Revolution. The restoration of religion in the reform era has ushered in a period of dramatic religious revival but has also brought a variety of challenges to the Party's authority.Footnote 4 Chinese Buddhism and Taoism have been hailed as model religions and are routinely perceived to have a less contentious relationship with the regime.Footnote 5 The state's favouritism towards these two religions can be seen in its recent policy of religious “sinicization,” which demands that religions in China incorporate Chinese characteristics into their beliefs and practices.Footnote 6 This seemingly amicable relationship, however, obscures a highly controversial dimension of the interactions between the communist state and the Chinese Buddhist and Taoist establishments: religious property and, particularly, the commodification of temple assets by agents of the state.

Religious commodification, also known as “religion building a stage to sing an economic opera” (zongjiao datai jingji changxi 宗教搭台经济唱戏), has been a popular local developmental strategy since the 1990s. It manifests in various forms, including constructing temples and outdoor Buddha statues for tourism purposes, leasing temples, publicly trading temple assets and impersonating monks. According to the central authorities, these practices violate state regulations, disturb normal religious activities, profane religious sentiment and defame Chinese religions. The commercial exploitation of temple assets has been the defining challenge of the state's management of Chinese Buddhism and Taoism. In addition to a series of central prohibitions,Footnote 7 the recently revised Regulations on Religious Affairs (which came into effect in February 2018) – the highest level of religious regulation in China – seek to ensure the religious use of temples by stipulating that a religious group has the right to access and manage the state-owned and collective properties which it legally occupies.Footnote 8

This paper investigates the contentious use of temple assets, an understudied and yet focal point of the state–temple relationship in China. What drives local state-led religious commodification? Amid the central state's repeated failure to rein in its local agents, how do temple leaders maintain the religious use of temple assets? What impact does this contention have on state control over organized Chinese Buddhism and Taoism?

Research Data

This paper covers the period from the 1979 publication of a People's Daily editorial calling for the implementation of a policy of religious freedom to the end of Xi Jinping's 习近平 first term in office in 2017.Footnote 9 The qualitative and observational data come from interviews, official documents, regulations, research papers, news archives and publications issued by the Chinese government as well as by religious associations. The fieldwork was conducted between June 2012 and May 2015, during which time I investigated the property politics of 22 historic Chinese Buddhist and Taoist temples. These temples are predominantly located in eastern and south-central China, which is home to almost two-thirds of the 163 temples of national significance. I selected these temples as they represent the variation in religious commodification. In most cases, I had direct access to the temples’ leaders and sites not open to the general public. Between April and July 2013, I worked as a volunteer-in-residence at one of the temples in order to learn how a free-access temple operates. Although they make up only a small portion of the full spectrum of temples in China, historic temples are significant because they disproportionately affect the state's religious policy. Thus, a study focusing on this group of temples helps to shed light on the relationship between the state and temples in contemporary China.

Temple Commodification as an Institution

A temple can be the materialization of, among other things, a local community's desire to rebuild a previously oppressed collective identity, the clerical activism of individual monks and nuns who aspire to have their own lineage homes, an overseas religious community's search for ancestral roots for authenticity, or the entrepreneurship of business men and women who seek to profit from religious tourism.Footnote 10 Scholarly attention paid to these diverse interests and the concerns of a variety of social actors has enabled researchers of contemporary Chinese religions and politics to situate temple reconstruction in the nexus of religious revival, tourism and economic development. Previous literature has found that temples often form a symbiotic relationship with the local government when their interests converge, for instance for charities, public welfare projects and tourism.Footnote 11 Yet, this collaboration has also created potential conflicts as local state interests rarely move beyond economic development. Religious leaders run the risk of corroding their spiritual authority by being associated with such economic interests.Footnote 12 Furthermore, conflicts almost always arise when it comes to the allocation of temple revenues, the use of temple property and the accessibility of the temple.Footnote 13 This research builds on the literature but focuses on the state and monastic institutions whose distinctive logics inevitably foster contention over the use of temple property.

“Building a stage to sing opera” (datai changxi 搭台唱戏) as a phrase and a strategy emerged from the rural development of the 1980s when local governments sought to mobilize surplus rural labour to support industrial production by providing the capital and technical support for small township and village enterprises.Footnote 14 By the late 1980s, the strategy had extended to tourism. Religion, owing to its still ambiguous status, entered into the frame under the rubric of “culture building the stage to sing the economic opera.” This developmental move was in response to the increased demands for temple reconstruction in the reform era. According to the China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database, the phrase “religion building the stage to sing the economic opera” first appeared in 1993.Footnote 15 The first official prohibition of such a practice was issued in 1994.Footnote 16 Despite being banned, the practice has, however, not ceased. To the contrary, its popularity among local state agents in the form of large outdoor religious statues has led to multiple references being made in the recent Regulations on Religious Affairs which forbid the commercial exploitation of religion.Footnote 17

Popular temples have a proven track record in attracting tourists and capital flow – a golden recipe for local GDP and fiscal revenues. In 2017, for example, the famous Buddhist pilgrimage centre, Mount Putuo 普陀山, welcomed 8.58 million visitors, which amounted to an admission income of 878 million yuan.Footnote 18 The direct income from a temple and its spill-over effects, including tourism consumption and the accompanying employment and taxation gains, have driven growth-minded local governments to mine the temple economy.

Local leaders’ motivation to benefit materially from temples derives from the cadre responsibility and evaluation system by which local cadres are evaluated according to a wide range of specific performance criteria, such as industrial output, taxes and profits remitted, fiscal income, retail sales, population growth rate, grain output, infrastructural investment realized, and compulsory education completion rate.Footnote 19 These criteria are assigned points, based on their degree of priority, and are divided into soft targets, hard targets and veto targets, which are tied to the promotion and annual bonuses of local leaders. Hard targets are almost always linked to economic criteria. Veto targets (yipiao foujue 一票否决) are political in nature, and the failure to achieve them cancels out all other successful achievements. This incentive structure is “high-powered” because strong performances generate payoffs that account for a large portion of the cadre's total income.Footnote 20 The leading cadres of a locality are evaluated by the next level up Party organ, but their bonus payment is financed by the locality's own collective funds. The percentage of cadres evaluated as excellent is limited, pitting local leaders against each other. The system therefore ensures state control over local state agents while maintaining local initiatives for economic development – an institutional arrangement fundamental to China's rapid economic growth.Footnote 21 Performance-based promotion particularly affects leaders at the lower level of government.Footnote 22

Local leaders are driven to pursue hard targets often at the cost of other incompatible tasks. This is further exacerbated by frequent cadre rotation.Footnote 23 According to the Olsonian theory of “roving vs. stationary bandits,” short time horizons incentivize the rational self-interested roving bandits to plunder and absolve them from accounting for the long-term consequences of their decisions.Footnote 24 This problem of “moral hazard” is well captured in a study by Sarah Eaton and Genia Kostka of the local implementation of environmental policies in three provinces, Shanxi, Hunan and Shandong.Footnote 25 Based on the data gathered on 898 municipal Party secretaries appointed between 1993 and 2011, it was found that local leaders in China had surprisingly short tenures, averaging 3.8 years. The study suggests that given the time pressure to perform in order to gain promotion, local leaders often select quickly visible and measurable projects despite the damage that these would do to efficient and sustainable growth.

The concentration of power in the Party secretary and the pressure to produce short-term economic growth more often than not override the protection duties of each functional department. For example, in a letter to the directors of lower-level departments concerned with protecting cultural relics, a provincial cultural bureau chief advised his subordinates not to openly confront the law-breaking and profit-seeking local leaders since this would only result in a meaningless sacrifice:

[Our] economy is growing rapidly; front runners naturally get to reap the greatest benefits … Some local governments inevitably resort to ideas and measures in order to bring about quick returns … But in the work of cultural relics, how [do we] stop the law-breaking behaviour of individual leaders? This is a matter of art and skills. First, [you] should report [the violation] in writing on behalf of [our] department to the said leaders as well as the next higher level department … Keep the documents of both issuing and receiving ends on file … to clarify responsibilities. Second, … do not talk about big principles to the leaders and to the related departments at various levels. Talk sense about where it matters. For example, [tell them that] the protection and good use of an ancient village can develop tourism … and increase village income … Third, let the People's Congress, Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, celebrities, and the masses speak on our behalf. Our small director's forthright opposition to the superior's improper policy is far less effective than that of the People's Congress, People's Political Consultative Conference, and celebrities. Even a joint petition of opposition by the masses is more effective than our opposition … Anyway, [you] grassroots directors … there is no need to tough it out against individual law-breaking leaders … and sacrifice in vain.Footnote 26

This same performance imperative has led to widespread local state initiatives to commodify temple assets and religious services, despite the repeated condemnations of the central authorities. As one Buddhist monk explained:

This is a matter of different interests … The centre and provincial governments may focus more on the [long-term] cultural and political effects that result, whereas local governments place more emphasis on local economic development. A local leader's promotion or demotion is contingent on economic development. Each term is only five years. As long as he ensures that no big social incident breaks out during his five-year tenure while he makes advances in the economy, he is likely to get promoted. Any repercussions from his tenure would be the problem of his successor … the benefits of promoting culture cannot be seen within one or two terms. [If he chooses to do so], he would be helping his [successors]/competitors by adding to their achievements. This has resulted in the short-sightedness of local officials. As far as they are concerned, the key is to turn a cultural brand into real, visible benefits during their tenure … [This is] the reason why local governments in China have constantly attempted to enclose famous mountains and great rivers (mingshan dachuan 名山大川) with scenic parks.Footnote 27

Unlike the institutional myopia of local Party leaders, the leaders of historic temples have a much longer-term outlook owing to beliefs that extend beyond this worldly existence, the spiritual lineage tradition and the immobility of historic temple assets.

The Logic of the Spiritual Economy

The Buddhist cosmology maintains that the universe is the result of karma, the law of causes and effects of actions.Footnote 28 People are bound to the cycle of death and rebirth (samsara), which spans millions of lifetimes. Good deeds bring better rebirths, whereas negative behaviour leads to bad results. Rebirth as a human is considered to be a privilege because the human faculty of free will and the combination of pain and pleasure that exists uniquely in the human experience is conducive to enlightenment through which one obtains a passage out of samsara.Footnote 29 Taoism has over the course of centuries appropriated Buddhist ideas about the afterlife.Footnote 30 Taoists believe that one can attain immortality through holistic self-cultivation to find harmony with the cosmic order (dao 道).

Merit (gongde 功德) is a Buddhist and Taoist reference to virtuous achievement. A person's stock of merit can bring benefits, such as immortality or deliverance from potential suffering, and a better rebirth, to this life and the life after. Merit can be transferred to another living person or redirected to the deceased. It can be earned and amassed through undertaking benevolent deeds and following the dao. In addition to doing good deeds, one can obtain merit by participating in Buddhist and Taoist rites. Ritual assemblies bring in crowds and provide opportunities for the temple to collect donations. Examples include regular ritual assemblies (every first and 15th day of the lunar calendar) and the annual festivals of the Taoist zhongyuan 中元 and Buddhist yulanpen 盂兰盆 (the 15th day of the seventh lunar month) when temples perform the rites of universal salvation (pudu 普渡) and almsgiving to hungry ghosts to deliver them from suffering, soothe their spirits, and therefore remit the harmful effects they might bring. Many temples also hold additional activities that cater to the interests of the community. Some temples, for example, perform merit rituals during the college and middle school entrance exams to give blessings to students hoping to gain better test results.Footnote 31

Most temples also provide a list of merit items that lay people can sponsor for themselves and their families. Common merit items can include the necessities that go with a ritual assembly (for example, altar construction, offerings, meals for participants), items for daily operation (for example, oil for eternal light, meals for the monks and volunteers, dharma instruments for the sangha, temple brochures), or materials for temple construction and maintenance (for example, statues, pillars, roof tiles, bricks, bells and drums). The price of a merit item can range from hundreds of thousand yuan to “merit donation at will” (suixi gongde 随喜功德). Lay people can also gain merit by volunteering at the temple. A free-access temple's day-to-day tasks, including cooking, gardening, cleaning, receiving guests, sales, tour-guiding and driving, rely heavily on lay volunteers. Individual contributions to the temple, regardless of the form and amount, are considered as equally meritorious and will therefore create boundless merit (gongde wuliang 功德无量). The continuous sponsorship of lay followers depends on the temple's welcoming reputation and its ability to sustain the belief that its followers are accumulating merit and advancing religiously.

The transhistorical nature of these beliefs tends to generate an outlook that extends beyond the rule of any political leader and has helped to sustain and is sustained by the fact that the existing major Buddhist and Taoist lineages and pilgrimage centres have outlasted all political governments in Chinese history. Regardless of the school, the concept of universal sangha allows all Buddhist lineages to be traced back to the Buddha; the line of the Celestial Master of the Taoist Zhengyi School has continued for 64 generations since it was first established in the second century.

The religious beliefs and the institutional practice of undisrupted spiritual linages influence the temple leaders’ view of the physical temple and its relationship with the political government. First of all, temples are immovable, which renders them vulnerable to hostile governments. Historic temples are especially so because they are also irreplaceable. They are not just religious venues; they are the embodiment of their separate spiritual lineages. The survival of a historic temple's material and symbolic assets depends on state toleration, if not protection.

Second, temple properties are communal. Aside from being the nexus of social and spiritual life, a temple is above all the material manifestation of a communal network. Temple assets come from “ten directions” (shifang 十方). Temple construction and maintenance test a religious community's capacity to coordinate and pool resources. A successful temple often has a diverse and powerful patron base. The communal nature of a temple's properties means that the temple has the social and economic potential for popular mobilization.

Third, the majority of historic temples are also home to the sangha, making them not only immovable and communal assets but also residential sites. Most of these temples’ leaders are members of the local and national Chinese people's political consultative conferences or people's congresses. To the resident monks and nuns, a temple is more than a religious space: it provides all their social and material necessities, including education, shelter, livelihood, healthcare and old-age care. Residential monks therefore have a significant stake in the management of the temple. These temple leaders’ institutional positions have made them leading players in the contestation over the use of temple property.Footnote 32

Because a free-access temple operates through lay people's pursuit of religious merits, not only in the form of monetary donations but also in labour contributions, its leaders invest a great deal of time cultivating relations with lay followers. The logic of the merit economy is not based on commercial transactions but on merit exchange and accumulation under clerical leadership. A sizable free-access temple might therefore suggest an active religious leadership that is able to unite and mobilize the lay followers. However, commodified temple access and religious services can cripple a temple's religious functions and hinder the leadership of the sangha. It can also lead to a net loss of temple income that would otherwise be reinvested in religious development.

In sum, the pressure of pricing historic temple access and religious services is constant. Financially, temple leaders need income to support the sangha as well as the daily operation and maintenance of a temple. Politically, local state leaders, who control the Party apparatus, are incentivized to exploit temple properties commercially. To maintain free access, the temple leadership must keep the temple financially solvent while simultaneously resisting external pressures to commodify temple assets. The admission policy of an individual temple thus signals the degree of autonomy enjoyed by the religious leaders of that temple.

Admission as a Measurement of Religious Commodification

Owing to the disparities in institutional preference, local cadres and religious leaders tend to diverge on the usage of religious sites and temple incomes. On the one hand, self-interested local officials strive to produce short-term, measurable economic returns from temple commodification. On the other hand, religious leaders aspire to revive their spiritual lineage and monastic institutions by building a sustainable merit economy. As previously mentioned, religious commodification comes in a range of forms, but setting up a religious scenic park, which is managed by the local state-owned tourist agency or management committee, has been the standard formula. By enclosing a temple within a park, the local state is able to create and monopolize income otherwise unavailable to it, for example from admission fees, transportation, incense sales, and so on.

Park authorities and temple leaders often hold conflicting views regarding the use of temple property, but the tension drew public attention when the tourist agencies of China's four major Buddhist pilgrimage centres sought initial public offerings (IPO). The first, Mount Emei 峨眉山, went public in 1997. The company included admission revenues (roughly 40 per cent of its total income) in the IPO, sparking public outrage about what was seen as the privatization of religious properties and profit-making from sacred symbols.Footnote 33 State policy has since ruled against such practices. Mount Jiuhua 九华山 successfully went public in 2015, without bundling its admission revenues, but Mount Putuo's and Mount Wutai's 五台山 recent IPO applications have been withdrawn or rejected owing to strong opposition from the religious community and its supporters in the central state.Footnote 34

As far as temple leaders are concerned, free access not only distinguishes a temple from those controlled by the government and other commercial interests but it also showcases the clergy's leadership role in the spiritual community. During my fieldwork, I found this to be a commonly held view among both religious leaders and lay followers, who frequently emphasized that free access signalled a temple's authenticity. It is true that amid local state-led religious commodification, a high admission fee has been associated with “religion building the stage to sing the economic opera,” using religion to rake in money (jiejiao liancai 借教敛财), religious commercialism and a lack of religious authenticity and spiritual authority. But why do some temples continue to charge admission?

Despite their preference, temple leaders have to adjust their behaviour according to the material and institutional resources available to them. After the Cultural Revolution, in order to re-establish temples as religious institutions, the sangha had to be revived and the physical temples reconstructed. At the time, there were very few practising monks and nuns left, and a new generation had yet to come of age. Temples in general were not equipped to perform ritual services and the lay community was yet to be established. Most temples were in need of repair and reconstruction, but the state policy of “self-supporting temples and self-financing reconstructions” (yisi yangsi, zichou zijian 以寺养寺, 自筹自建) in the early 1980s put a stop to financial aid from the government. Many temples resorted to collecting admission fees to support the sangha and fund temple reconstructions.Footnote 35 The early reliance on admission fee income reduced the urgency and necessity to cultivate a lay following, making it difficult for temples to become completely self-sufficient and withdraw from this initially expedient practice. Some continue to charge admission fees but their religious predilection would prevent them from charging high admission fees or commodifying religious services.

Varieties of Temple Autonomy

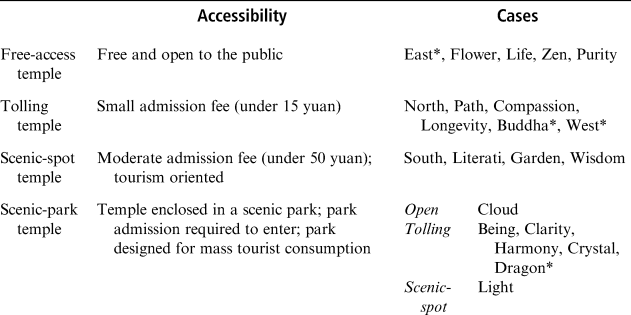

I chose to examine the state of affairs of 163 “temples of national importance.” These historic temples have prominent linages and were among the first sites to be selected by the Buddhist and Taoist communities to return to the religious community as part of the Party's policy of religious restoration in 1983. In 2013, 162 of the temples were open to the public. The highest temple admission fee was 80 yuan, the lowest was zero, and the average admission fee was six yuan. However, as 61 temples were located inside scenic parks, where additional admission fees were collected by the park management, the real average temple admission can be deemed to be 59 yuan. I identified four categories of temples based on their accessibility using temple admission: free access, tolling, scenic spot and scenic park (see Table 1).

Table 1: Temple Cases According to Accessibility in 2012

Notes:

* Changed category during the period of this research.

First, a free-access temple has a free-for-all entry policy, which means that it is able to maintain internal financial solvency and so resist external commodification pressure from local state agents. A free-access temple has the highest level of autonomy. Second, a tolling temple collects a small admission fee from non-members (i.e. visitors who do not provide proof of having converted to the religion) and does not share the admission income with any state agents. A tolling temple has a high degree of autonomy but has yet to achieve financial solvency through its merit economy. Third, a scenic-spot temple is officially classified as a scenic spot. It is also under the supervision of the tourism bureau whose interests in tourist flows often limit the religious leadership's course of action. In addition, the temple has to meet a variety of requirements with regard to tourist services, security, sanitation, transportation and communication. With higher operational costs, a scenic-spot temple's admission fee tends to be higher than that for tolling temples. Finally, a scenic-park temple is enclosed within a scenic park managed by a local state tourism agency. Visitors must purchase a park ticket before being able to access the temple. Temple leaders have little say in the management of the scenic park. Often, enclosed temples collect their own admission fees rather than partner up with the park authorities to set a unified price policy.

The cases in Table 1 were selected to capture the range of this variation. An analysis of the cases shows that the average admission fee rose from eight yuan to 31 yuan if park admission is included. Among the sites surveyed, the leaders of the five free-access temples all emphasized that free access was a marker of their religious authenticity, a discourse which resonated with the statements I collected from lay people. The evidence shows that, given the choice, a great majority of temples would prefer to charge lower, if not zero, admission fees.

A temple can transfer from one category to another depending on its internal material circumstances and ability to override external pressures to commodify temple access. Among the 22 temples surveyed, three changed their admission policies during the period of this research: Temple Dragon, Temple Buddha and Temple West. Temple Buddha and Temple West joined the ranks of free-access temples in 2012 after previously being a tolling temple and a scenic-park/tolling temple, respectively. The transition to free access is not unilinear. Temple Dragon, previously a free-access temple, became enclosed after the independent-minded leadership of Temple East withdrew from the site. In what follows, I will discuss in detail how the leaderships of all four temples confronted the pressure to commodify temple access.

Transition to free access: (re-)building religious authenticity

Temple West's transition to a free-access temple was only possible thanks to three decades of monastic reconstruction. According to the abbot, the temple used to be home to over 500 resident monks until they were forced to disband in 1969. By the end of the Cultural Revolution, most of the temple structure remained, but all sutras and statues were destroyed. It was one of the first temples to reopen, owing to its lineage connection with Japanese Buddhism. The government supplied the initial funding for the temple reconstruction, and 50 monks returned in 1980 – a small number compared to previous times, yet still remarkable when considering that these monks had recently endured severe persecution. After the state introduced the policy of “self-supporting temples and self-funding reconstructions” in 1985, the temple began to collect entrance fees.

Over the years, Temple West accumulated some assets as a tolling temple. By 2012, it had 110 monks in residence, a solid lay following and strong ties with overseas Buddhist communities. The monastic institution was well maintained because the new generation of monks were trained by a group of committed, elderly monks who still made up the substantive portion of the sangha. The current abbot described his appointment as a testament to the temple's long-held tradition as a public institution: if the residential monks are unable to agree on a new abbot among themselves, they “select the worthy from ten directions” (shifang xuanxian 十方选贤), based on the candidate's “integrity, Buddhist learning and patriotism.” Suffice it to say, the leadership of Temple West commanded the spiritual authority of a public temple. Yet, their decision to transition to free access was actually triggered by an external crisis.

Although the religious community reclaimed the temple's premises, the forest area that was historically considered to be an integral part of the temple was still controlled by the local forestry department, which charged a 20-yuan entrance fee. Beginning in October 2011, the district government blocked the path to the temple and the forestry area and imposed a 50-yuan admission fee. Visitors now had to pay 50 yuan to enter the forestry area and 60 yuan (50 yuan for the park entry and 10 yuan for the temple) to access the temple, which immediately reduced the number of tourists to the site by half. The temple therefore suffered a net loss in admission-fee income and donations and its religious outreach and reputation were also damaged. It was under this circumstance that the temple leadership pushed for the transition to a free-access temple.

Just six months after the path was blocked, the temple scrapped its entrance charge (10 yuan) and persuaded the local government to also lift the park admission (50 yuan). It was not a hard negotiation because the enclosure not only had failed to generate more revenue for the district government owing to the drop in tourist flows but it had also upset locals who had previously enjoyed low-cost access to both the temple (10 yuan) and the forest area (20 yuan). Faced with mounting criticism, the district authorities soon announced that local visitors could purchase the park ticket at a discounted rate of 20 yuan; the 50-yuan park admission remained in place for out-of-town tourists. The temple leadership was able to convince the government to re-open the path and reverted to its previous policy of charging 20 yuan for admission to the forest area. Now that there was no temple admission fee, the district government could hope to restore demand for the site and benefit from the popularity of a free-access temple.

The enclosure of Temple West and its conversion to a free-access temple affected Temple Buddha, which is only less than ten miles away. The district authorities had approached the Temple Buddha leadership multiple times with a scenic park proposal, which was repeatedly rejected by the monks. From a geographical perspective, enclosure of Temple Buddha would be unfeasible without the monks’ cooperation. Unlike Temple West, access to which is through government-controlled forest, Temple Buddha is located in an urban area. Enclosing the temple without the monks’ consent would require the local government to block access to the temple from all directions, making the project unworkable. During the enclosure of Temple West, Temple Buddha, then a tolling temple charging 10 yuan, received more tourists than Temple West for the first time, making Temple Buddha the true beneficiary of Temple West's enclosure. As might be expected, when Temple West proposed scrapping its entrance fee, Temple Buddha followed suit.

Temple West was not able to stop the district government from setting up a ticket booth on its doorstop until it became obvious that enclosure also hurt the political leadership as visitors voted with their feet and chose the much more accessible Temple Buddha. Temple West's leaders seized the opportunity to push for a change to free access in the hope that they could recoup the material and symbolic losses suffered by the temple during its enclosure. This move subsequently had an impact on its competitor, Temple Buddha. Both temples had been tolling temples for almost three decades and would probably have cancelled all admission fees eventually, given their institutional preference and improved material conditions. Yet, it was the crisis of enclosure that unexpectedly made free access the optimal choice for all parties involved, including the political leadership whose self-restraint was necessary not only for the creation but also consolidation of a free-access temple, a point to which I now turn in a comparison of the cases of Temple East and Temple Dragon.

The consolidation of free access: the role of local state agents

The reconstructions of Temple East and Temple Dragon were initiated by the prefectural governments with a view to expanding incoming tourism. The two governments invited the same eminent Buddhist master to re-establish the monastic institutions. Under their religious leaders, both temples had successfully inspired local followings. They were also presented as shining examples of their respective local governments’ achievements to upper-level officials on inspection tours. The religious leadership, however, withdrew from Temple Dragon after three years owing to the incessant conflicts with the political leadership over the temple's admission fees. It did, however, manage to consolidate Temple East's free-access status by signing a formal contract with the local government which protected the temple from any future enclosure.

Temple East was rebuilt from scratch half a mile away from its original site, in line with the “relocation and rebuilding” (yidi chongjian 异地重建) strategy. This approach to temple revival is often used as the majority of temple structures in China were either completely destroyed or occupied by the state for other purposes over the course of a century of conflict and regime hostility. The prefectural government presented the reconstruction proposal to the temple's most famous living disciple, an abbot who had received dharma transmission in the historical Temple East, making the temple home to the spiritual lineage he had inherited. Since the original Temple East was completely erased and its original site had become a residential area, the local government proposed three locations for the abbot to choose from. One of them was in a scenic park that the authorities had already begun to construct; it was also the one that the abbot chose because of its splendid scenery, infrastructure and largely unpopulated space.

Locals returned three stelae that they had rescued from the original temple before it was destroyed. The government provided the first piece of land (a quarter of the land needed for the project) in 2004 to assist the reconstruction. The temple leadership would be responsible for funding the rest of the project and the government would provide the infrastructure around the temple.

The relationship between the local state and temple was initially amicable; however, the local public security monitored the temple's activities closely and, according to the monks, would arbitrarily stop a ritual assembly if it had not been made aware of the event beforehand. The constant local interventions caused a slowdown of the temple's expansion plans and forced the temple leadership to be more transparent with the local government with respect to its operations. This change had generated positive results:

We've learned to inform the government about our activities. They were suspicious at the beginning, but now they understand that we pose no threat. They have even been advising us about convenient ways to plan our activities. If a specific method won't work owing to official policy restrictions, they will help us to find an alternative.Footnote 36

The tensions arising from the state's demand for social control were basically resolved after Temple East became more transparent in the eyes of the local officials. Temple East's willingness to accommodate the regime's security concerns was shared by the leaders of other temples, who often stated explicitly in the interviews: “Buddhism (Taoism) does not oppose the Communist Party.” Yet, the abbot was well aware that this seemingly cordial relationship was owing to the lack of religious competition and the temple's contribution to the local profile and economy.

Of course, the government would [continue to] watch us and other religious groups would [still] be jealous. The local Buddhist Association is small, but we still have to respect them as our superior. We pay the annual membership fee. The bigger the temple, the higher the fee … This city was not famous. The local government wanted development. We have brought in tourist flows and we've created a very good image for the local government.Footnote 37

Over the years, the government had tried multiple times to fence in the scenic park and each time was dissuaded by the temple leadership. To counter the repeated pressure to enclose the park that stemmed from the frequent rotation of local cadres, the temple eventually proceeded with a formal contract:

Many local governments look at the temple as a source of revenue. The prefectural government developed the surrounding area as part of the attempt to enclose the temple so that they could collect admission fees. But the Master would never agree. He has made it clear that the moment we have to collect entrance fees to survive is the moment we close the temple. He has communicated with the local government and made the Party secretary promise that his commitment will still be binding to his successors. [Therefore,] we signed a contract with the local government, and [the contract] has the official seal on it.Footnote 38

The monks viewed free access as the marker of the temple's authenticity and their commitment to spread the dharma. It was mentioned in the standard introduction that the monks and lay volunteers presented to visiting groups of pilgrims. It also allowed the temple to attract an average of 2,000 visitors on a normal weekday. The small donations collected from the merit boxes (gongde xiang 功德箱) were enough to cover the utilities of the entire temple. The temple had two vegetarian restaurants, which were run exclusively by volunteers. The clergy held biweekly ritual assemblies to provide ritual services to the community and to attract donations. The temple funded its reconstruction by attracting separate donations through a list of merit items. “Where there is dharma, there is a way. The Buddha will not let me starve,” the abbot told me. With a viable merit economy and commitment in the form of a formal contract with the local government, Temple East finally consolidated its free-access status.

Similarly, all that was left on the original site of Temple Dragon was a pagoda. The prefectural government decided to build a new temple adjacent to the pagoda and make the complex a tourist attraction. The government planned a 77-acre scenic park and invested nearly 40 million yuan in the first stage of construction, which was completed in 2009. Meanwhile, the authorities, hoping to find additional funding for the temple's reconstruction, approached Temple East's leaders, who saw this invitation as an opportunity to revive Buddhism in a different area. Following the same model that was applied to Temple East, the leaders of Temple Dragon were expected to establish the temple's monastic institution and raise funds for the second and final stages of reconstruction. The local government would be in charge of land expropriation, including the cost of compensation and the relocation of local residents.

The monks in Temple Dragon were instructed by their master to do all the hard work but let the local government claim the credit, a strategy that had worked well for Temple East. At the opening ceremony, the temple leadership mobilized nearly a hundred volunteers. In addition to the leaders from various temples and Buddhist associations, the provincial propaganda minister, deputy heads of the provincial religious bureau and cultural authorities attended the ceremony. The event also attracted thousands of lay people and tourists who participated in the ritual assembly led by the abbot. A ceremony of this kind was a great public relations coup for the leaders of the local government, who would not normally have had the opportunity to sit side-by-side with provincial-level officials. Temple Dragon became a popular destination for local leaders wishing to impress guests, so much so that the managing monks grumbled about finding the time to accommodate the various ranks of visiting cadres (who rarely bothered to notify them in advance) into their already busy schedule. The leaders of Temple East had to receive government officials as well, but since the temple's spiritual authority was already well established, they were no longer expected to personally receive political leaders from below the prefectural level.

Like Temple East, Temple Dragon held biweekly ritual assemblies which were open to the general public. In addition, the monks held Sunday dharma learning sessions whose regulars included the wives of local cadres. The free and high-quality ritual services quickly allowed the temple to develop a devout following. More importantly, the temple introduced a new way of practising Buddhism to the local community, which previously had not had much exposure to the sangha and religious services other than through simply visiting temples and making donations. Temple Dragon's success thus directly challenged the monopoly of the nearby Temple Unity.

Temple Unity was reconstructed in 1993 as one of the tourist attractions in a scenic park. Over the last decades, the temple leadership and the local authorities had forged a symbiotic relationship. The abbot provided local officials with economic rent and political loyalty in exchange for his ascendancy in the local Buddhist association and protection against accusations of misconduct such as drinking, gambling, bribery, misappropriation and violations of celibacy. As Temple Dragon's presence became an obvious threat to the existing local Buddhist establishment, Temple Unity's leaders exploited the government's distrust of mass gatherings by accusing Temple Dragon of spreading anti-government teachings during its ritual assemblies. The trust between Temple Dragon and the local authorities became even more precarious when a new local government cadre took office and Temple Dragon rejected his proposal to charge and split admission fees. In addition, the authorities had failed to expropriate enough land for further reconstruction. The Temple East leadership eventually decided to end its partnership with the local government and withdrew from Temple Dragon, which at the time created an outcry on the government's online forum.

Our followers were all crying as they were helping us pack … The prefectural government's online message board was flooded with messages requesting the government not to let us go. The authorities even asked us to tell our followers to stop posting messages. But those messages were left mostly by people who had visited the temple but were not followers themselves.Footnote 39

After the monks left, the government introduced a more cooperative temple leadership. Temple Dragon soon began to charge admission fees and the reconstruction effort was resumed, but this time with the support of Temple Unity and the local Buddhist association.

The four case studies show that a temple's transition from one category to another represents a change in its material circumstances and negotiation power vis-à-vis the local state agents. The move towards free access indicates an increasingly confident temple leadership capable of converting its spiritual authority into material income and political capital. Yet, the attitude of the local state remains the dominant factor in the religious usage of temple property. The leaders of all four temples avoided direct confrontation with the local authorities. This is because in an authoritarian setting, a temple's daily operations depend on the non-interference of the local state. Temple Dragon's leaders were forced to abandon the reconstruction project in the face of an increasingly hostile local government that was colluding with the co-opted monks occupying the leadership positions in the local Buddhist association.

Conclusion

This paper situates the commodification of and contestation over temple property in the institutions of local economic development and the material circumstances of the monastic institutions. I argue that the Chinese Communist Party's emphasis on economic growth has created behavioural incentives for local state agents to commodify temple assets, despite such practices violating the Party's own religious policy. As a countermeasure and given the choice, temple leaders strive for a donation-based merit economy in order to gain control over temple assets and demonstrate their spiritual authenticity. Hence, a temple's management autonomy must be negotiated on two fronts: internally with lay followers, so as to establish a sustainable merit economy, and externally with local state agents, by demonstrating political conformity and emphasizing the temple's economic contributions. These findings show the contradictions in the Chinese state's management of organized Buddhism and Taoism and help us to understand the antinomy of authoritarian state legitimation. In addition, the focus on property politics reveals the material foundation of organized Buddhism and Taoism's resilience as well their weakness: the merit economy helps to sustain the temple as a religious institution and enhances the leadership's spiritual authority. But, owing to the immobility and irreplaceability of historic temple assets, temple leaders try to avoid antagonizing local authorities, which in turn restricts a temple's potential for social mobilization. It is true that free access is demonstrative of a temple's institutional strength and a local state–temple relationship that is simultaneously contentious and conciliatory; however, as such management autonomy must operate within the authoritarian state's regulatory framework, organized Buddhism and Taoism's restrained contestation actually helps to strengthen the state's control over these religions.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their useful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Biographical note

Kuei-min CHANG is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica, Taipei. Her research interests include religion and politics, authoritarianism, property and state formation.