Background

Off-label placement of the Melody® valve (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, United States of America) in the mitral position in infants and young children was first reported in 2012 by Abdullah et.al. (Boston technique).Reference Abdullah, Ramirez, McElhinney, Lock, del Nido and Emani1 The current literature is limited to a number of reports which either describe different techniques of surgical valve implantationReference Hofmann, Dave, Hübler and Kretschmar2–Reference Stephens, Tannous, Nugent, Hauck and Forbess4 with only two case series and one case report describing catheter techniques that address other valve-related issues such as adjusting the valve size for somatic growth, valve stenosis, and paravalvular leaks.Reference Quiñonez, Breitbart, Tworetsky, Lock, Marshall and Emani5–Reference Sullivan, Wong, Kim and Ing7 We present a case study where severe paravalvar leaks were tackled using large low-pressure balloons in a child who had previously undergone Melody valve implantation in the mitral position.

Case report

A 14-kg 3-year old girl with Shone’s complex underwent two unsuccessful mitral valve repairs (that included resection of a supramitral membrane) followed by two mechanical valve replacements in the supra-annular position. Both mechanical valves prostheses (19-mm Saint Jude®) failed due to obstruction, within 6 and then 3 months of implantation. Removal of both mechanical valves revealed florid pannus formation with secondary thrombus formation, which significantly impinged on the valve mechanism, restricting leaflet motion. The mean echocardiographic gradient was 25 mmHg over the second mechanical valve at representation.

Given the preceding history, an 18-mm Melody® valve was implanted surgically as per the Boston Group technique (shortening and trimming the valve, creating a wide V shape opening to the outflow and distal valve stent fixation to the posterior left ventricular wall). The Melody® valve was balloon expanded up to 18 mm as this valve came to replace the obstructed 19-mm Saint Jude® valve. An atrial septal fenestration was created to facilitate future dilatation of the valve as necessitated by the somatic growth of the patient.

Following implantation of the Melody®valve, the patient developed complete heart block and a permanent pacemaker was implanted after 2 weeks of inpatient review. The mean estimated inflow gradient, post-operatively, through the valve was 4 mmHg and there was no regurgitation or paravalvar leak.

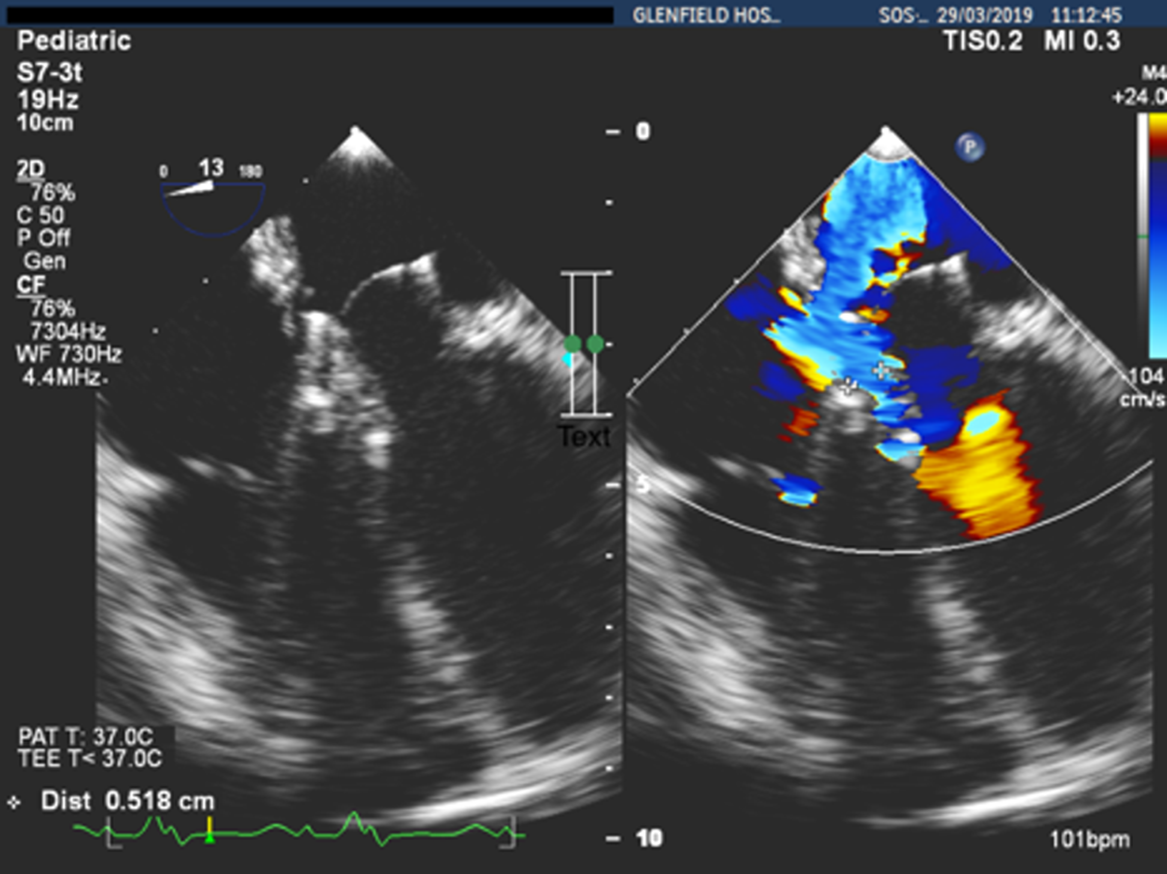

During follow-up, two mild paravalvular leaks were documented on echocardiography. Five months after valve implantation, the child presented with symptoms and signs of right heart failure. Echocardiography then showed the two previous paravalvular leaks: one anterolateral with a vena contracta of 3 mm, and a second one posteromedially with a vena contracta of 5 mm (Fig 1). The atrial septal fenestration was still open with a diameter of 4 mm and was associated with a left to right shunt (Fig 2).

Figure 1. Posteromedial leak with a vena contracta of 5 mm.

Figure 2. Atrial septal fenestration (ASF) covered by the atrial part of the Melody valve.

A multidisciplinary discussion concluded that an interventional attempt to dilate the valve through the fenestration was indicated. Although the inter-atrial fenestration appeared to give an easy and direct approach to the valve, at catheterisation this proved not to be the case as progressive enlargement of the left atrium appeared to have pushed the fenestration slightly inferiorly where it was overlapped by the posterior struts of the valve stent. Hence, only a Terumo 0.018 inch wire could cross through this, making balloon dilatation impossible.

After giving consideration to these findings, it was felt that a hybrid approach with transapical access to the left ventricle would give an easier, straight, and direct approach to the valve, which would enable valve dilatation using large balloons.

The procedure was guided by transoesophageal echo in order to demonstrate (in real time) abolishment of the paravalvular leaks and to assess any iatrogenic obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract due to stent distortion following balloon dilatation. Additionally, the transoesophageal echo could give us clear picture of the balloon positioning prior to the inflation as well as the leaflet positioning in systole and diastole in order to avoid the risk of dilating the valve during systole and distorting the leaflets of the Melody®valve.

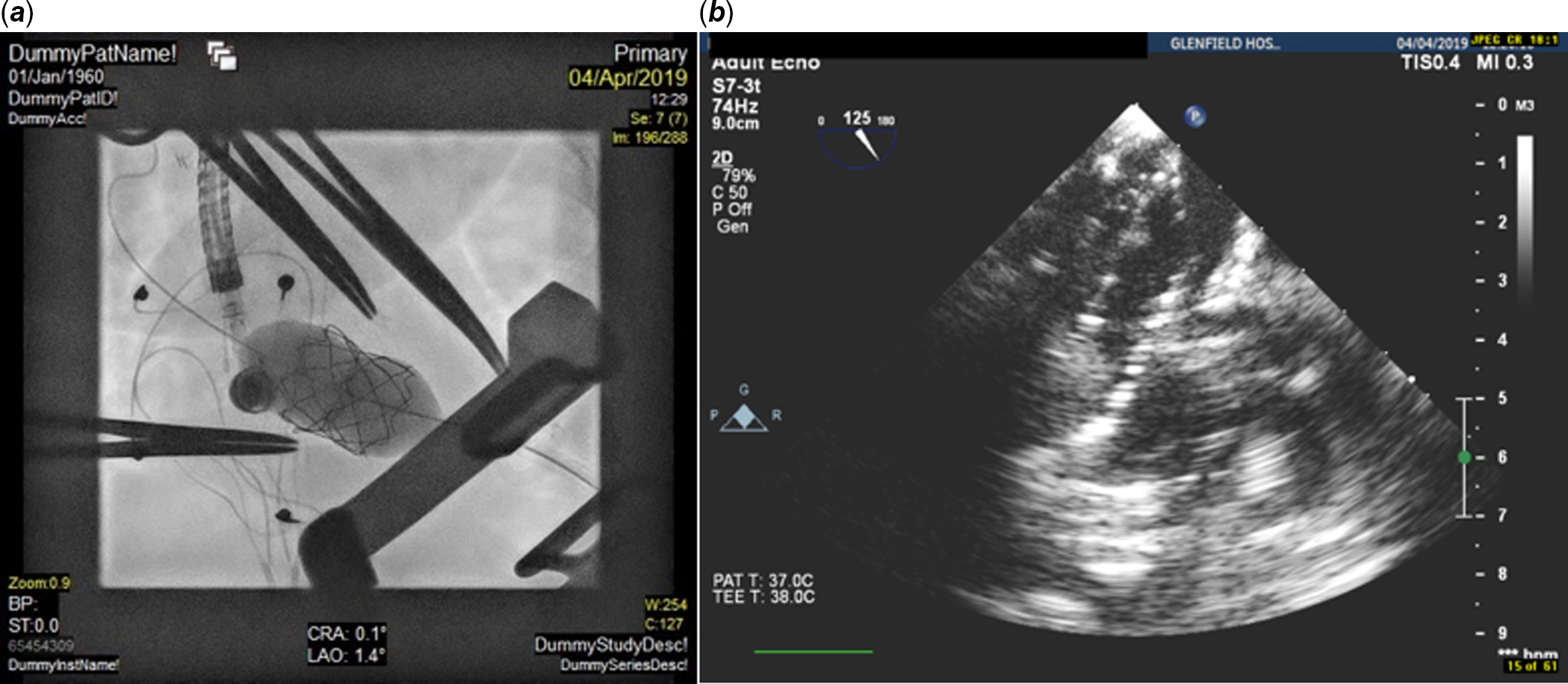

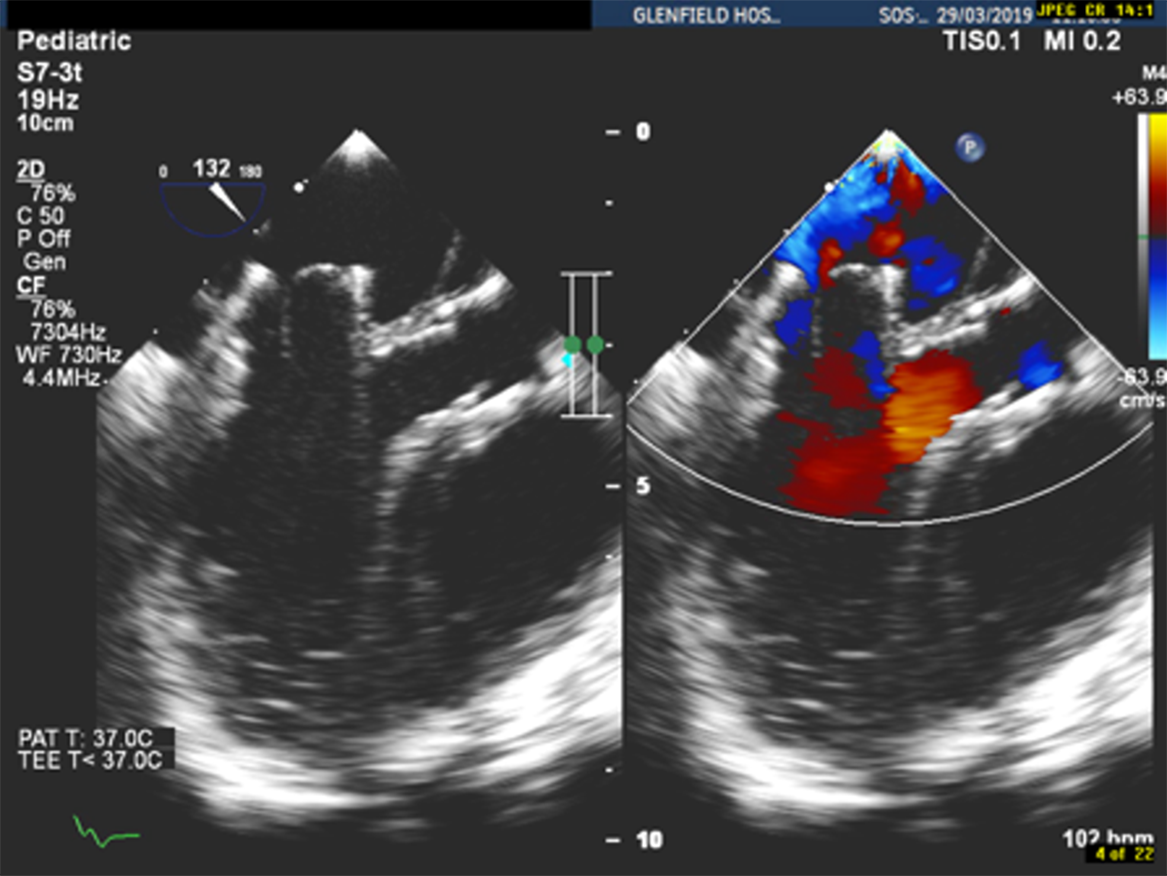

After opening the chest with a left mini-anterolateral thoracotomy (over the apex beat), a purse string suture was placed in apex of the left ventricle. A 6-F sheath was initially inserted and then exchanged with a 12-F Cook short sheath. Under transoesophageal echo guidance, the tip of the 12-F sheath was placed just at the apex of the left ventricle. Subsequently a 4-F multipurpose A2 (MP A2 Cordis) catheter was introduced into the cavity of the left ventricle. With a Terumo J-tip guiding wire, the valve leaflets were crossed and then the A2 catheter was passed over this wire and placed in the left atrium. The pressure gradient between the left atrium and left ventricle end-diastolic pressure was measured at 11 mmHg. As soon as the catheter was placed in right upper pulmonary vein, an Amplatzer super stiff exchange wire was placed in order to have stability during balloon dilatation. The valve was gradually dilated up to 24 mm with low-pressure balloons (Fig 3). The final outer diameter of the valve on fluoroscopy was 22 mm. Transoesophageal echo assessment showed abolishment of the paravalvular leak, an unobstructed left ventricular outflow tract, and the right and left lower pulmonary veins were seen to be free of any obstruction (Fig 4).

Figure 3 ( a, b ) Fluroscopy and TOE images of dilatation of the Melody valve via a transapical approach with a 24-mm Z-Med II balloon.

Figure 4. LVOT free of obstruction after Melody valve dilatation of up to 24 mm. Final fluoroscopic diameter of the valve was 22 mm.

The duration of the procedure was 165 minutes with a screening time of 11 minutes and radiation dose of 166.1 cGy/m2. The patient was transferred to the paediatric ICU for recovery. Over the following few days, the signs of right heart failure reversed, and the patient was discharged home, in good condition, 1 week following the procedure. At 18-month follow-up, there was neither demonstrable paravalvular regurgitation nor central jet of regurgitation seen on echocardiography (Fig 5).

Figure 5. Follow-up at 18 months after Melody valve dilatation.

Discussion

Following introduction in 2012,Reference Abdullah, Ramirez, McElhinney, Lock, del Nido and Emani1 surgical implantation of the Melody® valve in the mitral position remains an off-label indication for its use, and long-term results currently remain unknown.

Only two case seriesReference Hofmann, Dave, Hübler and Kretschmar2,Reference Langer, Solowiejczyk, Fahey, Torres, Bacha and Kalfa3 describe subsequent valve dilatation percutaneously; however, these do not give a detailed account of the technical aspects of the procedure. In contrast, the case report by Sullivan et al.Reference Sullivan, Wong, Kim and Ing7 gives a detailed technical account of how to access the valve with a transseptal approach. The main pathology encountered in Sullivan et al case, however, was mitral valve stenosis. The inner diameter of the valve was 10 mm and they dilated the valve with a high-pressure balloon of 14 mm. Due to slippage of the balloon towards the left atrium, the valve became distorted at the distal ventricular end. They resolved this by re-dilating the distal part of the valve.Reference Sullivan, Wong, Kim and Ing7

In our case, there was a fenestration of the inter-atrial septum, but this was found to be covered by the left atrium portion of the stent. Creation of the second fenestration slightly higher was feasible, but we thought that the curve of the sheath and the stiff exchange wire (in order to accommodate the large 30-mm and 40-mm-long balloons) could cause significant tension on the valve whilst crossing the valve and inflating the balloons. Even if we used a steerable Agilis® sheath would still cause a lot of tension on the valve and the atria wall, the trajectory of the balloon wire ensemble during full expansion of the balloon even at low pressure. We also posited that the two significant paravalvular leaks may have resulted from a gradual loosening of the sutures at the suture line. Taking these two issues into consideration, we concluded that a hybrid approach with transapical access to the left ventricle would give a straight and controlled route through the valve. We assessed that the risk of crossing the valve opposite to the leaflet opening could be overcome partially using a floppy Terumo J-tip guiding wire as it is described previously. Moreover, the shaft of the balloon and the balloon did not allow the coaptation of the valve leaflets keeping them in that way with an inclination towards the left ventricle. Additionally, the transoesophageal echo guidance gave us a continuous view of the valve leaflets during systole and diastole letting us the leaflet positioning during inflation.

Aspects of our approach proved to be useful. Our goal was to appose the stent of the Melody® to the wall of the left atrium and this was achieved effectively using low-pressure balloons, without causing a lot of stress on the valve leaflets and on the atrial wall. This was aided by the guide wire remaining straight through each dilatation, providing the appropriate stability for controlled dilatations of the valve. Transoesophageal echo was extremely useful in providing real-time information about the size and the position of the leaks, and haemodynamic evaluation of the left ventricular outflow tract and inflow of the valve after each dilatation.

Conclusion

The Melody® valve should be considered as a treatment option for mitral valve disease in children, especially there when other techniques have failed. This technique, as described by the Boston Group, can be performed safely. Re-adjustment of the valve size to the size of the mitral annulus is mandatory, especially when paravalvular leaks are present, and transapical access is a safe and sustainable alternative for dilatation with large balloons of the valve.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Prof. Mario Carminati for his support and his suggestions.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

This case description does not contain any study with animal performed by any of the authors.

All applicable and international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the case were followed.

The procedure performed in the case description was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or research committee and with the declaration and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent was obtained from the parents of the individual included in the study.