The original Inotrope Score proposed by Wernovsky,Reference Wernovsky, Wypij and Jonas 1 including dopamine, dobutamine, and epinephrine, was initially introduced as a measure of assessing total pharmacological support to aid interpretation of cardiac output measurements after the arterial switch operation.

The Inotrope Score and its more recent modification, the Vasoactive Inotrope Score,Reference Gaies, Gurney and Yen 2 have been used as markers of vasoactive requirements and surrogates for illness severity in cardiac critical care for the past two decades.Reference Friedland-Little, Hirsch-Romano and Yu 3 – Reference Bradley, Simsic, Mc Quinn, Habib, Shirali and Atz 9 The scores were originally not intended as illness severity scores, but they have been validated as predictors of early clinical outcomes after newborn and infant cardiac surgery.Reference Davidson, Tong, Hancock, Hauck, da Cruz and Kaufman 10 – Reference Gaies, Jeffries and Neibler 12

The advent of the electronic medical record and computerised physician order entry in day-to-day practice has brought with it the potential for more detailed interrogation of patient data, and importantly the ability to accurately study the temporal relationship between clinical status and multiple therapeutic interventions over a defined time period.Reference Leu, O’Connor and Marshall 13 A further refinement of the vasoactive score that can be easily calculated from the electronic medical records and computerised physician order entry, incorporating start and stop dates as well as dose changes, over specific time periods and across all age groups could be of additional utility in defining risk in postoperative cardiac patients. In order to further refine the Vasoactive Inotrope Score, we developed a modification of the Vasoactive Inotrope Score, which is the Total Inotrope Exposure Score. The Total Inotrope Exposure Score brings together cumulative vasoactive drug doses, together with dose adjustments, over time in infants and children of all ages after cardiac surgical procedures requiring cardiopulmonary bypass. The aim of this study was to compare and explore the association between this new vasoactive score – the Total Inotrope Exposure Score and outcome – and the established Vasoactive Inotrope Score in children undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass.

Materials and methods

Patients and demographic data

The study population included patients who were admitted to the cardiovascular ICU after open heart surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass at Texas Children’s Hospital between September, 2010 and May, 2011. These patients were already part of a prospective study of postoperative cortisol levels that was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Baylor College of Medicine. The population for the present study included all cases after the introduction of the Electronic Medical Records system in the institution. Demographics and clinical details such as age, surgical complexity by Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery (RACHS-1) score,Reference Jenkins, Gauvreau and Newburger 14 cardiopulmonary bypass time, cross-clamp time, duration of ventilation, ICU and hospital length of stay, hospital mortality, and need for cardiopulmonary resuscitation or mechanical circulatory support were collected. All data were extracted from the electronic medical record (EPIC Systems, Verona, Wisconsin, United States of America).

Vasoactive scores

Vasoactive Inotrope Score calculation

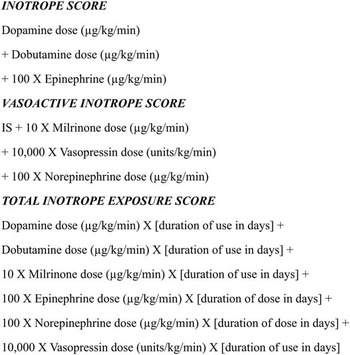

The score was calculated as proposed by Gaies et al by adding coefficients to the vasoactive medications and calculating the mean and the maximum scores over the first and subsequent 24-hour period after surgeryReference Wernovsky, Wypij and Jonas 1 , Reference Gaies, Gurney and Yen 2 (Fig 1). The mean and maximum Vasoactive Inotrope Score at 24 and 48 hours after surgery (VISmean24, VISmax24, VISmax48, VISmean48, respectively) were calculated for all patients.

Figure 1 The inotrope scores. Inotrope Score; Vasoactive Inotrope Score; and Total Inotrope Exposure Score.

Total Inotrope Exposure Score calculation

This score uses the same coefficients, or weighting, for a given vasoactive drug – for example, 100 for Epinephrine and 10 for Milrinone – that were used in the Vasoactive Inotrope Score (as shown in Fig 1); however, instead of calculating the average score or maximum at 24 and 48 hours in a conventional way, a time factor was added for each individual vasoactive drug to derive the new score. The Total Inotrope Exposure Score incorporates all changes to the vasoactive drug therapy throughout ICU admission.

Consider the following example – if, for a given patient, Milrinone at 0.25 μg/kg/minute was used for 1.75 days and Epinephrine at 0.02 μg/kg/minute was used for 0.5 days, the VISmean24 and VISmax24 would be 3.5 and 4.5, respectively. To derive the Total Inotrope Exposure Score, a time coefficient was added. Thus (Milrinone=0.25×10×1.75=4.3)+(Epinephrine=0.02×100×0.5=1) would give a Total Inotrope Exposure Score of 5.3. If the inotropes were stopped and re-started within the 48-hour period, the score corresponding to the inotrope and duration of time was added to give the total inotrope score. Dose changes were similarly incorporated in to the score. In summary, Total Inotrope Exposure Score is a weighted summation of the inotropes used in the ICU. It is mathematically not very dissimilar to the VISmean48. The power of each of the scores – VISmean24, VISmax24, VISmean48, VISmax48, and Total Inotrope Exposure Score – to predict the primary and secondary outcomes was studied as outlined below.

Analysis

The primary outcome was a composite measure of poor outcomes. This included death before hospital discharge and the need for cardiopulmonary resuscitation or extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation. If multiple poor outcomes including death occurred in the same patient, then the scores were calculated till death; otherwise, the computation of scores was stopped when a primary outcome occurred. The secondary or additional outcomes were prolonged ventilator support and prolonged ICU and hospital stay, and these were considered to be prolonged if they were in the upper 75% for the outcome of interest for the cohort.

Descriptive statistics are given for demographic, clinical, and outcome data using means and standard deviations, medians and 25th and 75th percentiles, or frequencies and percentages as appropriate. To define the best metric for the primary and secondary outcomes, the receiver operating characteristic curves for VISmean24, VISmax24, VISmean48, VISmax48, and Total Inotrope Exposure Score were compared using the log-rank test and confidence intervals to represent plausible values for the true population. Logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between the inotrope scores and outcomes with and without adjusting for baseline characteristics. Kaplan–Meier curves were analysed for freedom from invasive mechanical ventilation, extubated for at least 48 hours, time to ICU discharge, and time to hospital discharge. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess the relationship of the inotrope scores and the time to event – freedom from invasive mechanical ventilation and ICU and hospital stay. Multiple Cox proportional hazards models were used to adjust for baseline characteristics. Analyses were conducted with and without repeated observations.

Results

The study cohort included 167 separate admissions with 10 (6%) patients having more than one surgical admission. The study cohort included 37 (22.2%) neonates and 65 (41.3%) infants aged between 1 month and 1 year. The mean (standard deviation) age was 2.9 (6.0) years. The other demographic and patient details are shown in Table 1. Nearly a quarter of the cohort had higher-complexity operations with a RACHS-1 category of 4–6. The 75th centile cut-off for the duration of ventilation, ICU stay, and hospital stay were 4.8, 9, and 26 days, respectively Thus, durations exceeding these respective cut-offs were considered to be prolonged.

Table 1 Patient characteristics

CBP=cardiopulmonary bypass; CVICU=cardiovascular ICU; ECMO=extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation; RACHS-1=Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery; VIS=Vasoactive Inotrope Score

* Three patients had more than one adverse outcome

Primary outcome

The primary outcome – death or other adverse events – occurred in six out of the 167 admissions in the cohort. The Total Inotrope Exposure Score had an area under the curve of 0.92 (0.86, 0.97) (Fig 2a). A Total Inotrope Exposure Score cut-off value of 23.5 best predicted poor outcome in the cohort with a sensitivity of 85.7% and a specificity of 87.5%. The unadjusted odds ratio for a poor outcome was 42 (4.8, 369.6). Although the area under curve was higher than other scores as shown in Table 2, this difference did not reach statistical significance at the 0.05 level. As a poor outcome was present in only 4% of the cases, multiple logistic regression was not performed. Results were similar after excluding patients with repeated observations.

Figure 2 ( a ) Total Inotrope Exposure Score (TIES) and Vasoactive Inotrope Score (VIS) average 24 for predicting primary outcomes; ( b ) Kaplan–Meier curves predicting freedom from mechanical ventilation. ROC=receiver operating characteristic.

Table 2 Receiver operating characteristic of scores as predictors of primary outcome.

AUC=area under curve; CI=confidence interval; TIES=Total Inotrope Exposure Score; VISavg24=average Vasoactive Inotrope Score at 24 hours; VISmax24=maximum Vasoactive Inotrope Score at 24 hours; VISavg48=average Vasoactive Inotrope Score 24–48 hours; VISmax48=maximum Vasoactive Inotrope Score 24–48 hours

Secondary outcomes

The Total Inotrope Exposure Score best predicted prolonged ventilation with an area under the curve of 0.88 (0.81, 0.95) compared with VISmean24–0.73 (0.64, 0.82) (p=0.0001), VISmax24–0.74 (0.66, 0.83) (p=0.0011), VISmean48–0.74 (0.65, 0.82) (p<0.0001), and VISmax48–0.67 (0.58, 0.77) (p<0.001). The odds ratios for an association with prolonged ventilation after adjustment for factors that were significantly associated with increased length of ventilation on univariate analysis, including age, weight, use of preoperative ventilation, a high RACHS-1 score, and stress dose steroids, were calculated. Total Inotrope Exposure Score was the best predictor of prolonged mechanical ventilation with an adjusted odds ratio of 13.6 (3.9, 47.8) at a cut-off of 17.6. None of the other scores significantly predicted prolonged ventilation after adjusting for covariates in a multiple regression.

Similarly, the adjusted odds ratio for a prolonged ICU stay was predicted by the Total Inotrope Exposure Score as 12.7 (3.51, 45.7) at a cut-off of ⩾17.6. The other scores that predicted a prolonged ICU stay were VISmean24⩾4.5 OR 4.3 (1.3, 14.1), VISmax24⩾4.8 OR 7.3 (2.2, 24.2), and VISmean48⩾3.1 OR 3.5 (1.1, 10.7). The odds ratios for a prolonged hospital stay were 4 (1.37, 11.66) and 12.2 (2.5, 60.9) for VISmean48 and Total Inotrope Exposure Score at cut-offs of 3.1 and 17.6, respectively.

As the Total Inotrope Exposure Score is time dependent, in order to test its ability to predict secondary outcomes at different time points, Cox proportional models were used to assess the relationship of the different scores with the secondary outcomes – freedom from ventilation or ICU or hospital stay. As expected, this decreased with increasing scores (hazard ratio <1). After adjusting for age, weight, height, surgical risk, cardiopulmonary bypass, and cross-clamp times, the Total Inotrope Exposure Score best predicted freedom from ventilation with a hazard ratio of 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) (p=0.001). The corresponding Cox proportional models for freedom from prolonged ICU and hospital stay are shown in Table 3. Results were similar after excluding repeated observations. We also calculated the Cox regression models for assessing freedom from prolonged ventilation, ICU stay, and hospital stay for “high” and “low” scores according to the receiver operating characteristics cut-offs as shown in Figure 2b.

Table 3 Adjusted Cox proportional models for secondary outcomes.

CI=confidence interval; CVICU=cardiovascular ICU; HR=hazard ratio; TIES=Total Inotrope Exposure Score; VISavg24=average Vasoactive Inotrope Score at 24 hours; VISmax24=maximum Vasoactive Inotrope Score at 24 hours; VISavg48=average Vasoactive Inotrope Score 24–48 hours; VISmax48=maximum Vasoactive Inotrope Score 24–48 hours

Discussion

Our single-centre, exploratory study has shown that the new Total Inotrope Exposure Score may prove to be a useful, objective marker of postoperative vasoactive quantification and risk after paediatric cardiac surgery. The Total Inotrope Exposure Score was comparable with the Vasoactive Inotrope Score in its ability to predict death, cardiac arrest, or the need for extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation, although these primary outcomes were infrequent in our cohort. Total Inotrope Exposure Score performed superiorly to the Vasoactive Inotrope Score in its ability to predict prolonged ventilation and ICU or hospital length of stay, as might be expected, given that Total Inotrope Exposure Score is calculated beyond the first 48 postoperative hours. Importantly, this study represents the first application of a scoring system in paediatric cardiac patients undergoing surgery beyond infancy.

The Vasoactive Inotrope Score has previously been shown to predict mortality and morbidity in infants aged <1 year who may have a high vasoactive requirement because of a low cardiac output state early after cardiac surgery.Reference Gaies, Gurney and Yen 2 , Reference Davidson, Tong, Hancock, Hauck, da Cruz and Kaufman 10 , Reference Butts, Scheurer and Atz 11 The low cardiac output state is a significant cause of postoperative morbidity in young infants after heart surgery, with an onset typically occurring within 12 hours of ICU admission.Reference Wernovsky, Wypij and Jonas 1 , Reference Tweddell, Ghanayem and Mussatto 15 , Reference Duke, Butt, South and Karl 16 Although low cardiac output state may lead to early morbidity, not all adverse events are related to this. It has been recognised that adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes may be related to factors such as prolonged ventilation and hospital stay, which could in turn be related to secondary complications occurring in the ICU.Reference Newberger, Sleeper and Bellinger 17 – Reference Fuller, Nord and Gerdes 19 Thus, a score that is able to capture a prolonged use of vasoactive agents as opposed to just the immediate postoperative period may have additional merit.

The Total Inotrope Exposure Score offers the potential advantage of capturing events leading to increased inotrope support that may not necessarily be related to the typically early low cardiac output state after cardiopulmonary bypass but to other factors that may complicate the postoperative course after surgery. The score attempts to capture dose and time duration of use of vasoactive medication after surgery – akin to the area under the curve of the interventions. In addition, the score could potentially be used as a clinical tool for caregivers, particularly if integrated into the electronic medical charting system. In addition to tachyphylaxis, the prolonged use of inotropes, particularly catecholamines, has been shown to have a harmful effect on the myocardium and also cause immune-mediated injury.Reference Limperopoulos, Majnemer and Shevell 18 , Reference Stamm, Friehs and Cowan 20 , Reference Zhuo, Wu and Ni 21 In view of this, the Total Inotrope Exposure Score may provide a target for newer therapies to improve outcomes in patients. Another potential role for the Total Inotrope Exposure Score would be in the context of research, and in assessing the impact of clinical interventions on vasoactive therapies. Interestingly, none of the existing vasoactive scores have been validated in the non-cardiac population, and it remains to be seen whether the Total Inotrope Exposure Score could be applied in the general paediatric ICU, as well as to assess its performance in patients presenting with haemodynamic instability, actual or pending shock, or in the evolution of this in an existing patient. With the advent of the electronic medical record with computerised order entry, it would theoretically be possible to continuously derive the Total Inotrope Exposure Score for all patients.

There are several limitations to our study. The main limitations relate to the relatively small cohort, within a single centre, as well as the low frequency of occurrence of the primary outcome event – death or need for cardiopulmonary resuscitation or extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation – which together limit the power of the study. We would like to emphasise that these pilot exploratory findings need further validation in a larger population across different centres. Indeed, we were interested to observe that the Vasoactive Inotrope Scores in our cohort were in general lower than those in other published studies.Reference Gaies, Gurney and Yen 2 , Reference Davidson, Tong, Hancock, Hauck, da Cruz and Kaufman 10 , Reference Gaies, Jeffries and Neibler 12 , Reference Crow, Robinson, Bukhart, Dearani and Golden 22 This is at least in part likely to reflect our local practice of using very low, if any, doses of catecholamines and more routine use of vasodilators, with avoidance of hypertension. An associated limitation of this – and indeed any score that does not include objective clinical parameters – is that vasoactive practice is variable, as is the approach to weaning these. Thus, the score may vary according to institutional practice, and a high score cut-off for our institution may not necessarily apply to other institutions, or vice versa. Importantly, however, this limitation would equally apply to the Vasoactive Inotrope Score. Another consideration is the confounding effect of duration of use of vasoactives within the Total Inotrope Exposure Score and the potential linking of this with secondary outcomes such as length of ventilation and intensive care and hospital stay; however, the score was designed to represent a single number for the “area under the curve” for the use of inotropes and aims to capture not only the initial use of inotrope therapy perhaps related to the initial post cardiopulmonary bypass period but also a prolonged low-dose use of inotropes or a later re-institution or re-escalation of inotropes because of other reasons. Our numbers are limited to test this in the present study. Although the Total Inotrope Exposure Score is mathematically similar to the average Vasoactive Inotrope Score during the initial period, it also captures patients who may not easily wean off vasoactives and have a sustained need for an additional period of time. Our numbers are small to differentiate the two patterns of inotrope usage and the association with the time of occurrence of the primary outcome.

Future analyses of Total Inotrope Exposure Score should evaluate whether the score can accurately predict future events and duration of therapy – for example, the association of a Total Inotrope Exposure Score calculated on postoperative day 3 in a patient still mechanically ventilated with total duration of ventilation and ICU length of stay. This type of analysis may fully demonstrate the potential of a continuously updated vasoactive use score and its advantage over other existing scores that are calculated only in the early postoperative period. Much larger cohorts of patients would be necessary for such investigations, ideally including patients across institutions and representing varying practice patterns. There would be significant merit in incorporating this score into collaborative databases, which would give us the ability to “test” its validity more extensively.

Conclusion

The Total Inotrope Exposure Score is a new vasoactive score that, at this preliminary stage, appears to have predictive value for postoperative adverse outcomes after cardiac surgery in infants and children of all ages. This warrants prospective validation across larger numbers of patients and across institutions.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

Approved by the Institutional Review Board of Baylor College of Medicine.