The immediate goals of CPR for children experiencing an arrest are to deliver nutrient oxygen to peripheral vascular beds and reestablish spontaneous circulation. Since standard CPR provides only a limited percentage of normal cardiac output (approximately 15–30%), Reference Voorhees, Babbs and Tacker1,Reference Lurie, Nemergut and Yannopoulos2 blood flow to vital organs is severely compromised during prolonged resuscitation. As a result, increased duration of CPR has been associated with poor outcome. Reference Innes, Summers and Boyd3–Reference Matos7 Furthermore, the ability to achieve adequate “diastolic” blood pressures during the relaxation phase of thoracic compressions has been shown to be associated with outcome. Reference Meaney, Bobrow and Mancini8,Reference Morgan, French and Kilbaugh9 In adults, those who do not generate >16 mmHg diastolic blood pressure during resuscitation do not experience return of spontaneous circulation presumably due to poor coronary perfusion pressure. Reference Paradis, Martin and Rivers10 In children, Berg et al showed that a threshold diastolic blood pressure of 25 mmHg in those <1 year of age, and 30 mmHg in those >1 year of age, increased the probability of achieving return of spontaneous circulation. Reference Berg, Sutton and Reeder11 Standard approaches to elevate diastolic blood pressure during resuscitation include changing the force or location of compressions, allowance of full chest recoil, volume administration, and catecholamine/vasopressor administration. However, these treatments may have their own respective consequences such as heart distension (with worsened atrio-ventricular valve regurgitation and pulmonary oedema), and increased myocardial oxygen consumption. Thus, they may further strain the heart at a time when functional reserve is low and cardiac recovery is needed.

IAC-CPR is a technique in which force is applied to the abdomen during the recoil phase of chest compressions. It includes all elements of standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation, thereby serving as an adjunct to traditional resuscitation. IAC-CPR works by external force transmission through the abdomen to the aorta. This leads to an increase in aortic diastolic pressure and enhanced retrograde flow to the coronary arteries and prograde flow to the brain in a manner similar to intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation or external counterpulsation. Reference Taguchi, Ogawa and Oida12 It also results in hydrostatic compression of intra-abdominal veins, which advances blood into the thoracic compartment during the relaxation phase of chest compressions. This refilling of the intrathoracic blood pool improves cardiac output with subsequent chest compressions. Finally, IAC-CPR augmentation of baseline venous pressure coupled with maintenance of an adequate arteriovenous gradient overcomes capillary closing pressure and thereby improves vital organ perfusion. Reference Sack and Kesselbrenner13

IAC-CPR has been evaluated in both animals and adult humans. In a canine resuscitation model of electrically induced ventricular fibrillation, IAC-CPR was found to increase oxygen delivery, arterial systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and cardiac output compared to standard CPR. Reference Voorhees, Niebauer and Babbs14 IAC-CPR has also been shown to augment carotid arterial flow in dogs by direct intravascular measurement. Blood flow averaged 22.8% of control values during IAC-CPR versus 8.7% during standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Reference Einagle, Bertrand and Wise15 More recently, these data were corroborated in a swine ventricular fibrillation model. Animals receiving IAC-CPR as opposed to standard CPR during arrest demonstrated greater systolic and diastolic blood pressure, coronary perfusion pressure, and end-tidal CO2 (as a surrogate measure of cardiac output). Return of spontaneous circulation was greater in the IAC-CPR cohort, and neurologic examinations in survivors who received IAC-CPR were superior to those who underwent standard CPR. Reference Georgiou, Papathanassoglou and Middleton16

Human studies of IAC-CPR have yielded similar benefits. Data from four randomized clinical trials of IAC-CPR have shown improved resuscitation rates and survival for adult patients experiencing in-hospital cardiac arrest. Reference Babbs17 Formal meta-analysis of all clinical trials of IAC-CPR versus standard CPR revealed improvement in the rate of return of spontaneous circulation by 10.7% (p = 0.006), and a trend toward increased hospital discharge with intact neurologic function of 8.7% (p = 0.06). When meta-analysis was limited to in-hospital trials (n = 279), return of spontaneous circulation was 52% with IAC-CPR versus 26% with standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation (p < 0.0001). This suggests that only 4 patients would need to be treated with IAC-CPR to achieve return of spontaneous circulation in one additional patient. Reference Babbs18

IAC-CPR has been recommended as an acceptable alternative to standard CPR for adult in-hospital resuscitation (Class IIb recommendation per the American Heart Association guidelines). Reference Cave, Gazmuri and Otto19 However, no experimental data on which to make paediatric recommendations, either for or against IAC-CPR, yet exist. Our interest in IAC-CPR arose from our clinical observation that children with palliated single ventricle lesions and shunt-dependent pulmonary blood flow are extremely difficult to resuscitate with good outcomes owing to their severe hypoxemia during CPR; and our concern that increased intrathoracic pressure transmitted to the lungs during standard CPR may limit pulmonary blood flow and reduce efficacy of resuscitative efforts. Thus, we postulated that IAC-CPR might provide a novel mechanism for counteracting the problem of pulmonary blood flow limitation during single ventricle resuscitation by increasing blood pressure during CPR “diastole,” and directly enhancing retrograde (in Blalock-Taussig-Thomas) or prograde (in Sano) shunt perfusion. Furthermore, we hypothesised that the increase in pulmonary blood flow during IAC-CPR would not diminish cardiac output compared to standard CPR via a steal phenomenon. Rather, IAC-CPR would increase overall cardiac output in addition to pulmonary blood flow through augmentation of venous return.

Materials and methods

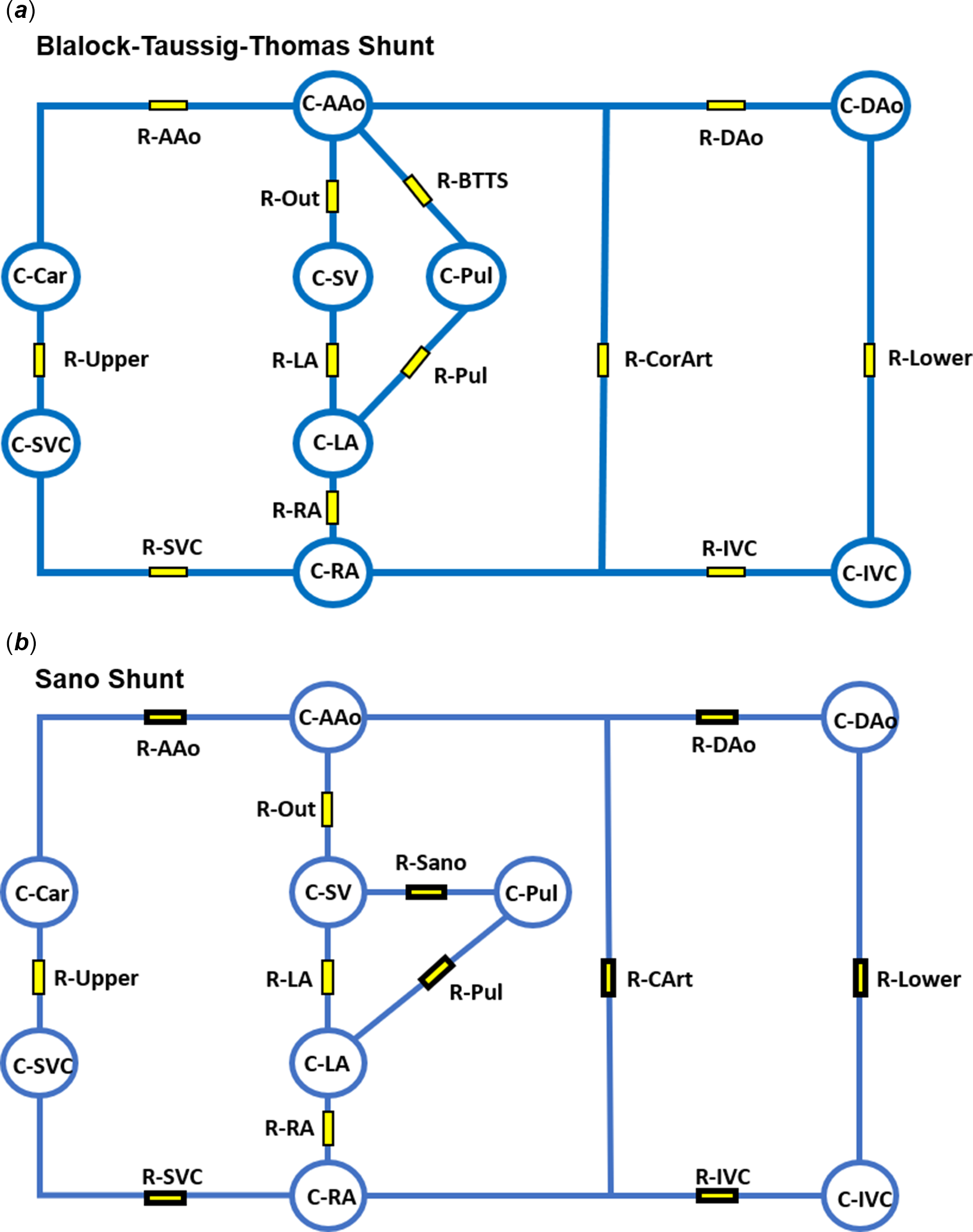

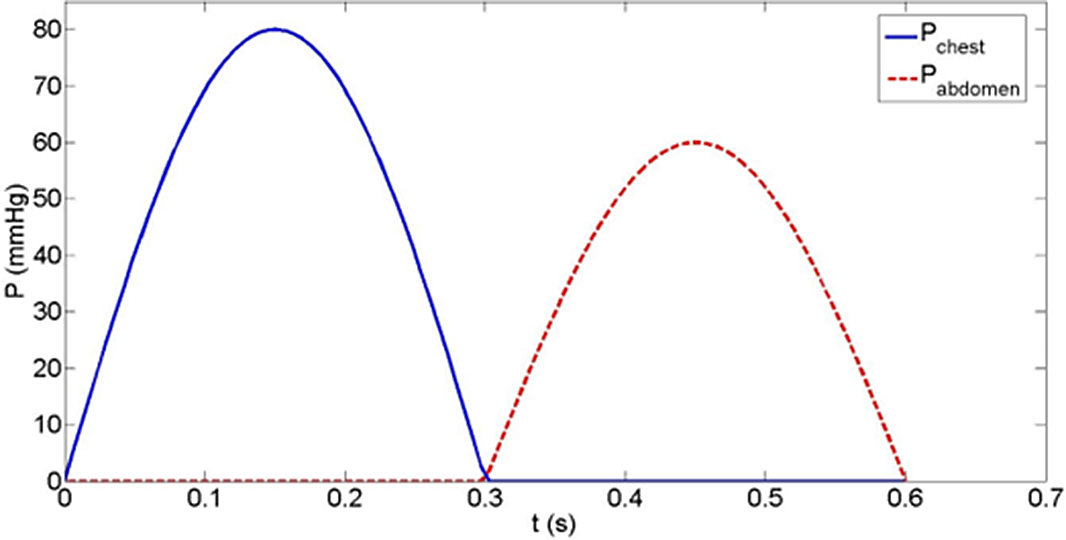

We employed a previously described lumped parameter model wherein heart chambers and blood vessels are represented as a series of resistor and capacitor circuits to simulate blood flow. Reference Babbs20 The lumped parameter model was modified to represent single ventricle circulation with either a Blalock-Taussig-Thomas or Sano shunt (Fig 1). By making an analogy between blood flow and electrical current in which pressure drop is analogous to voltage, and flow rate is analogous to current, flow Q through a vessel was determined by Ohm’s law (Q=P/R), where P is the pressure drop across the vessel and R is the resistance. For a capacitor that represents vessel compliance, the flow–pressure relationship was given by dP/dt = Q/C, where C is the capacitance (Fig 2a). When an external force is applied to the capacitor chamber, we defined dP/dt = Q/C + (dP_chest)/dt, where P chest is the compression pressure; the same reasoning was applied to abdominal compression using P abd during IAC-CPR (Fig 2b). To model the aortic, atrioventricular, and internal jugular valves, unidirectional flow was allowed for R_Out, R_LA and R_SVC. By applying these pressure-flow equations to each component in the lumped parameter model, we derived an ordinary differential equation system that was solved numerically by a standard explicit fourth order Runge-Kutta method. Since initial pressures and flow in the lumped parameter model were set to zero, and variations between cycles due to the transient response of resistors and capacitors existed before a stable state was achieved, we simulated 15 cycles to obtain periodic results and used the last five cycles to calculate the quantities of interest. Time integration step size was set to 0.00075 second to avoid numerical oscillations caused by a large step size.

Figure 1. Schematic of single ventricle blood vessels and heart chambers represented as a series of resistor and capacitor circuits. ( a ) BTT shunt with connection between the aorta (C-AAo) and pulmonary arteries (C-Pul). ( b ) Sano shunt showing connection between the single ventricle (C-SV) and the pulmonary arteries (C-Pul). Capacitors: C-AAo = ascending aorta, C-Dao = descending aorta, C-IVC = inferior vena cava, C-RA = right atrium, C-LA = left atrium, C-Pul = pulmonary arteries, C-SV = single ventricle, C-Car = upper body arteries, C-SVC = upper body vessels/superior vena cava. Resistors: R-AAo = ascending aorta, R-Upper = upper body vessels, R-SVC = superior vena cava, R-RA = atrial septum, R-LA = atrio-ventricular valve, R-Out = neo-aorta, R-Sano = Sano shunt, R-BTTS = BTT shunt, R-Pul = pulmonary vessels, R-CArt = coronary vessels, R-Dao = descending aorta, R-Lower = lower body vessels, R-IVC = inferior vena cava. BTT = Blalock-Taussig-Thomas.

Figure 2. ( a ) Modifications of Ohm’s Law for resistors and capacitors in the lumped parameter model applied to single ventricle physiology. ( b ) Definitions of dP/dt relative to chest or abdominal compression. Key: Q = flow, P = pressure, R = resistance, dP/dt = change in pressure over time. P chest = pressure of chest compression, P abd = pressure of abdominal compression.

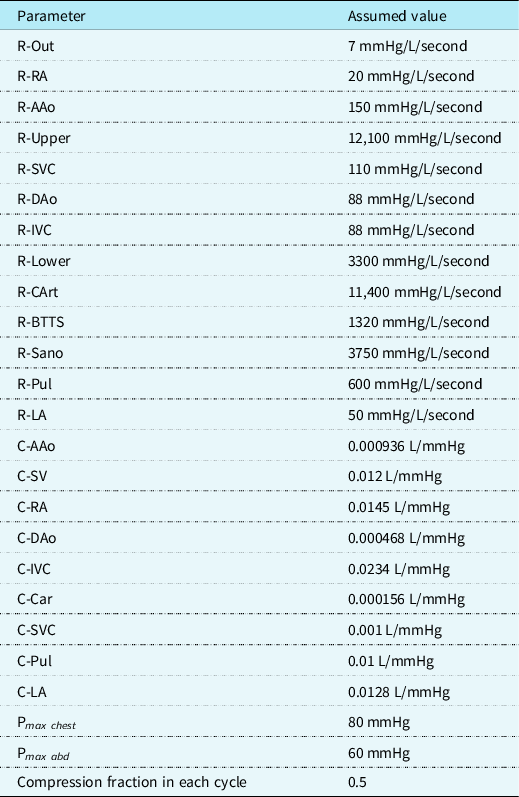

Assumed values for haemodynamic parameters are listed in Table 1. These were modelled after haemodynamic catheterisation data of single ventricle patients from within our institution in the last 2 years, and from published data. Reference Babbs20 For all forms of CPR, a chest compression rate of 100 was employed per American Heart Association Pediatric Advanced Life Support Guidelines. Reference Topjian, Raymond and Atkins21 External pressures (max 80 mmHg) were applied to the heart chambers and great vessels. One hundred percent force transmission was applied to the single ventricle, whereas 80% was applied to the pulmonary arteries to simulate a gradient for forward flow. IAC-CPR was modelled in both types of single ventricle palliations by adding additional phasic compression pressures (max 60 mmHg) to the abdominal aorta. A duty cycle of 50% was employed with half-sinusoidal functions (Fig 3). Reference Babbs20 Hemodynamic values are expressed as means, and percent differences between them.

Figure 3. External compressing pressures in chest and abdominal compression cycles. Note the 50% duty cycle, the 80 mmHg max chest pressure, and the 60 mmHg max abdominal pressure.

Table 1. Input values for lumped parameter model

Results

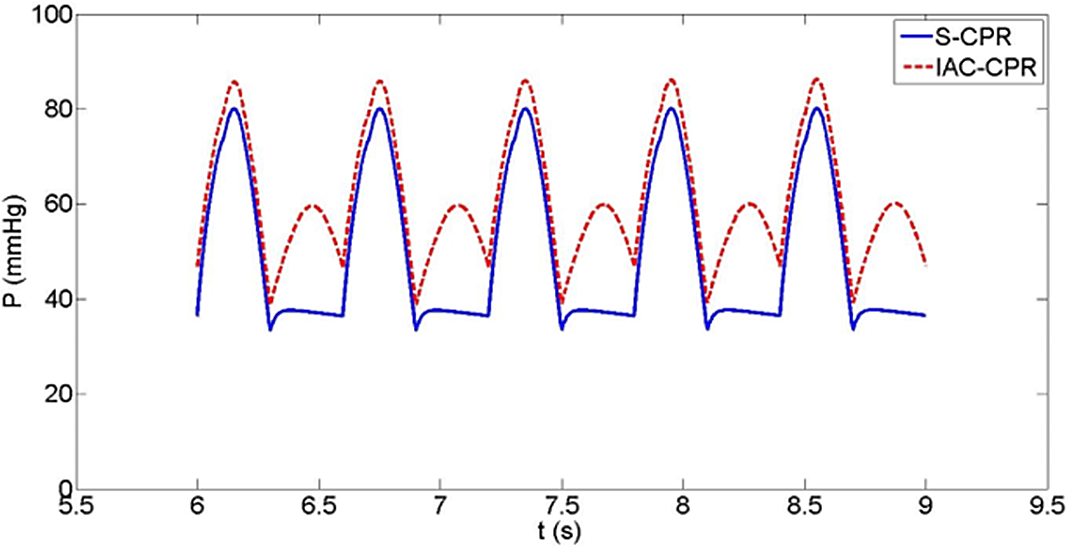

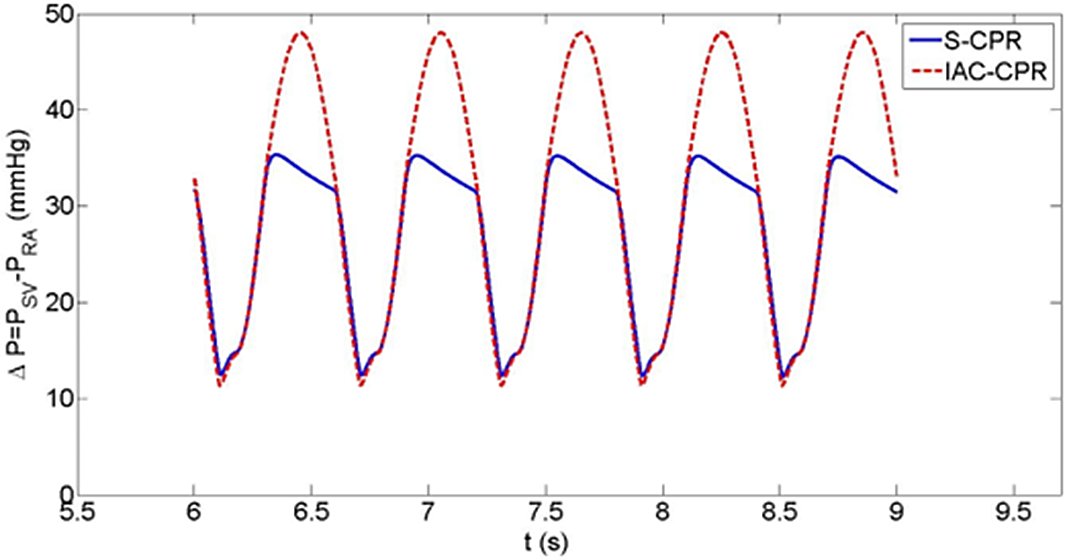

In the Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt model, pulmonary blood flow during IAC-CPR was 30% higher than pulmonary blood flow during standard CPR (0.92 versus 0.71 L/minute). Moreover, this did not occur at the expense of systemic cardiac output, as cardiac output in IAC-CPR was increased by 21% (1.75 versus 1.45 L/minute). Diastolic blood pressure was also higher during IAC-CPR (16% increase, 36 versus 31 mmHg, Fig 4), as were coronary perfusion pressure (17% increase, 27 versus 23 mmHg, Fig 5) and coronary blood flow (17% increase, 0.14 versus 0.12 L/minute). Systolic blood pressure was improved by IAC-CPR, though only by 8% (84 versus 78 mmHg).

Figure 4. Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt haemodynamics showing a higher diastolic blood pressure during IAC-CPR.

Figure 5. Coronary perfusion pressure during IAC-CPR in the Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt haemodynamics.

In the Sano model, pulmonary blood flow during IAC-CPR more than doubled compared to standard CPR (0.1 versus 0.04 L/minute). However, Sano pulmonary blood flow was considerably lower during both forms of CPR compared to the Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt condition due to a greater assumed shunt resistance, and a reduced pressure gradient from the single ventricle to the pulmonary arteries. Cardiac output was improved in IAC-CPR by 13% (0.94 versus 0.83 L/minute), as were diastolic blood pressure (18% increase, 39 versus 33 mmHg, Fig 6), systolic blood pressure (8% increase, 86 versus 80 mmHg), coronary perfusion pressure (15% increase, 31 versus 27 mmHg, Fig 7), and coronary blood flow (14% increase, 0.16 versus 0.14 L/minute).

Figure 6. Sano shunt haemodynamics also showing a higher diastolic blood pressure during IAC-CPR.

Figure 7. Coronary perfusion pressure during IAC-CPR in Sano shunt haemodynamics.

Discussion

IAC-CPR has been shown to increase “diastolic” blood pressure during the relaxation phase of chest compressions, thereby enhancing retrograde coronary perfusion and prograde cerebral blood flow. Reference Voorhees, Niebauer and Babbs14,Reference Hoekstra, van Lambalgen and Groeneveld22 In theory, this diastolic blood pressure elevation should also augment flow through any shunt capable of producing aortic run-off, such as an aorto-pulmonary, or Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt. However, this phenomenon has never been studied during CPR nor scientifically demonstrated. Our investigation, using a single ventricle mathematical model, has demonstrated that IAC-CPR may augment Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt flow, and thus, pulmonary blood flow (by 26%) compared to standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation. In addition, our construct suggests that IAC-CPR increases both pulmonary blood flow and cardiac output (by 20%) compared to standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation, thereby avoiding a detrimental scenario in which the technique diminishes much-needed systemic output by preferentially routing blood to the lungs.

In a similar manner, IAC-CPR in the Sano model increased pulmonary blood flow and cardiac output by 100 and 15%, respectively, compared to standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation. However, Sano shunt flow was significantly lower than that of the Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt. The lower pulmonary blood flow calculated for the Sano model was not surprising given that Sano pulmonary blood flow is dependent upon the gradient between the right ventricle and pulmonary arteries at all points in the resuscitation cycle. This gradient is modest during chest compressions due to raised intrathoracic pressure in cardiopulmonary resuscitation systole, while during cardiopulmonary resuscitation diastole there is no aortic driving pressure to improve pulmonary perfusion as there is with a Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt.

The cardiac output in our model was determined by the pressure gradient between the ventricle and the ascending aorta (C-SV and C-AAO, Fig 1) since the resistance R-out was kept unchanged. Thus, in the presence of a Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt which increases cross-sectional area for flow and aortic runoff, the pressure gradient (and cardiac output) is increased. In contrast, the ventricular-aortic pressure gradient with the higher resistance Sano shunt is smaller, resulting in a lower calculated cardiac output. In both single ventricle palliation types, an increase in cardiac output was seen during IAC-CPR. This is concordant with a recent adult trial in which IAC-CPR increased end-tidal CO2, a surrogate measure of cardiac output, by 38% versus standard CPR. Reference Movahedi, Mirhafez and Behnam-Voshani23

The 19% increase in diastolic blood pressure demonstrated during IAC-CPR improved hemodynamic profiles – there was an increase in coronary perfusion pressure (13%) and coronary blood flow (17%) in the Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt model, and in the Sano model (coronary perfusion pressure increased 19%, coronary blood flow increased 14%). These virtual findings are consistent with the known physiologic effects of IAC-CPR seen in animal studies and human trials of the resuscitation technique. Reference Hoekstra, van Lambalgen and Groeneveld22,Reference Lindner, Ahnefeld and Bowdler24,Reference Adams, Martin and Rivers25 For example, in a recent swine ventricular fibrillation model, coronary perfusion pressure was increased by 19%; other animal models have demonstrated two-fold coronary perfusion pressure elevations, while human measurements have shown more modest improvements. Reference Lindner, Ahnefeld and Bowdler24–Reference Wenzel, Lindner and Prengel27 Similarly, in a ventricular fibrillation canine resuscitation model using microspheres, coronary blood flow was improved by 22.7% with IAC-CPR. Reference Voorhees, Ralston and Babbs28 These correlations imply that our model may accurately reflect hemodynamic conditions during CPR. Accordingly, our results may portend better outcomes for single ventricle patients who undergo IAC-CPR versus standard CPR.

While it is known that outcomes from single ventricle resuscitation with conventional CPR are poor, the influence of shunt type remains unclear. Single ventricle children have a higher rate of arrest, likely due to increased myocardial work demand on the single ventricle from volume overload, imbalances in Qp:Qs, and shunt occlusions. They also have a greater chance of demise from an arrest, and an increased need for rescue extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Reference Gupta, Tang and Gall29 Lowry et al, using an administrative inpatient database, demonstrated that single ventricle patients have five-fold increased odds of cardiac arrest compared to children with a biventricular circulation. Furthermore, single ventricle patients exhibit decreased survival after CPR (mortality OR 1.7), even after adjustment for covariates. Reference Gupta, Tang and Gall29 Alten et al, using Pediatric Cardiac Critical Care Consortium data, documented an arrest rate in single ventricle patients near 16%, with survival that was only half that of cardiac arrest in other surgical categories. Reference Alten, Klugman and Raymond30 Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation, utilised for failure to achieve return of spontaneous circulation after an arrest, is also common, occurring in 13–20% of stage one postoperative patients. Risk factors for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation include low birth weight, longer cardiopulmonary bypass time, small ascending aorta (<2 mm), mitral stenosis with aortic atresia, intraoperative shunt revision, and a Sano RV-PA shunt type. Reference Roeleveld and Mendonca31 This suggests that Sano patients may have a less favourable response to CPR (thus necessitating extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation), a fact which may be corroborated by recent examination of the PICqCPR arrest cohort wherein survival to hospital discharge was much better among Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt patients than Sano patients (89% versus 38%, p < 0.05). Reference Yates, Sutton and Reeder32 If our model is accurate with regard to the level of cardiac output achieved during resuscitation of Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt versus Sano palliation patients, one could speculate that the lower Sano cardiac output explains the outcome difference.

It is also conceivable that single ventricle resuscitation outcomes are poor, and particularly those in Sano (vs Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt) patients, due to determinants of pulmonary blood flow. Chest compressions raise intrathoracic pressure and reduce pulmonary blood flow in both Sano and Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunted patients. Reference Peddy, Fran Hazinski and Laussen33 This results in systemic blood flow with low oxygen content, which in the presence of reduced coronary perfusion characteristic of CPR, may cause myocardial ischaemia. In addition, prolonged CPR in the setting of very limited pulmonary blood flow ultimately leads to progressively worsening oxygen delivery and end-organ injury. Sano patients must overcome the significant resistance of their lengthy pulmonary conduit and raised intrathoracic pressure during chest compressions to achieve pulmonary blood flow. Though Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunted patients tend to have shorter conduits with less resistance, they may experience pulmonary blood flow limitation both through raised intrathoracic pressure and poor diastolic driving pressure during CPR. The diastolic pressure achieved during CPR may be important to obtaining return of spontaneous circulation for reasons of coronary perfusion, but it may also be the case in single ventricle patients that diastolic blood pressure levels are crucial for pulmonary blood flow and systemic oxygenation. Given that IAC-CPR can augment venous return to the heart, raise cardiac output, and improve diastolic blood pressure, the technique could potentially increase pulmonary blood flow in both single ventricle constructs. In turn, this could enhance oxygen delivery and end-organ preservation. Such a mechanism is suggested by the findings of this mathematical model.

This study is limited by its virtual nature, and by the assumed inputs used which were not modelled for uncertainty and may only approximate the in vivo condition. Because our goal was to assess differences in physiologic parameters between IAC-CPR and standard CPR given reasonable inputs to the mathematical model, and not to validate the model itself, we did not perform sensitivity analyses of each physiologic component. The influence of different parameter values could be assessed in future studies, or an alternate single ventricle simulation model could be employed. Reference Jalali34 As previously published by Babbs, Reference Babbs20 only a half-sinusoidal function was used for external pressures which does not account for the possibility of compression release negative pressures. However, our model could be additionally refined to include compression data measured by a force sensor during CPR. In the lumped parameter construct used, the compliance of capillaries was not incorporated as a separate circuit element. Thus, we did not account for the possible effects of capillary closing pressure on venous capacitance (which in theory is overcome by IAC-CPR as another potential explanation for augmented cardiac output). In reality, CPR performance is very complicated and variable, influenced by periodic stoppages, with physiologic parameters changing over time. Nonetheless, IAC-CPR has been shown to be beneficial in several adult randomised trials. This fact, in conjunction with the preponderance of favourable animal data, and now our modelling information, should justify rigorous investigation of the technique in children. Furthermore, this study lends credence to the notion that CPR adjunctive techniques should be considered in paediatric cardiac patients to tailor resuscitative efforts to their unique physiology. However, the theoretical benefits of IAC-CPR for cardiac output in general, and coronary perfusion in specific, imply that the methodology need not be limited to cardiac patients alone. Non-cardiac patients may benefit from IAC-CPR once optimized methods for children are determined, instructions are disseminated, and caregivers are adequately trained. Such work is ongoing and may best be accomplished through multicenter resuscitation consortia.

Conclusions

We have employed an lumped parameter model of standard CPR and IAC-CPR in both Blalock-Taussig-Thomas and Sano single ventricle conditions. Results indicate that IAC-CPR augments Blalock-Taussig-Thomas shunt flow, and thus pulmonary blood flow, by 30% compared to standard CPR; pulmonary blood flow is also greatly increased by IAC-CPR in the Sano construct. In both models, cardiac output was increased by IAC-CPR, avoiding a potentially harmful steal phenomenon from the systemic circulation. Similarly, coronary perfusion pressure and coronary blood flow were increased during IAC-CPR.

This investigation is the first to advance IAC-CPR as a technique with mechanistically explicable utility in single ventricle patients with shunt-dependent pulmonary blood flow. Theoretical increases in pulmonary blood flow, cardiac output, and coronary perfusion pressure/coronary blood flow during IAC-CPR provide justification for rigorous clinical testing of the technique in children with and without congenital heart disease.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my collaborators at Stanford Engineering, Dr Alison Marsden and Dr Weiguang Yang, for their tremendous contributions to this project and the resultant manuscript.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant funding from any agency, either commercial or not-for-profit.

Conflicts of interest

None.