CHDs are the most common, clinically significant birth defect with a prevalence of approximately 1 in 200 live births. Reference Botto, Correa and Erickson1,Reference Moons, Sluysmans and De Wolf2 Given medical and surgical advances, the majority of infants with even severe CHDs now survive into adulthood but require life-long medical surveillance for potential complications. Tetralogy of Fallot and d-transposition of the great arteries with an intact ventricular septum are two such common CHDs that require cardiac surgery within the first days to months of life with excellent results but require ongoing evaluation in the outpatient setting. While numerous studies describe the prevalence of clinical complications in these populations, the timing and prediction of risk for any individual patient are poorly understood and evidence-based guidelines to inform long-term ambulatory monitoring are lacking and difficult to develop given patient variability.

Given these gaps in knowledge, paediatric cardiologists monitor patients in the ambulatory care setting largely according to personal, patient, institutional, and/or financial dictates. Both the frequency of physician visits and the use of medical testing may therefore vary widely and may do so for largely non-medical reasons. In other realms of medicine, studies demonstrate that marked practice variability contributes to variations in quality and costs. Reference Fisher, Wennberg, Stukel, Gottlieb, Lucas and Pinder3,Reference Fisher, Wennberg, Stukel, Gottlieb, Lucas and Pinder4 Minimising practice variability has the potential to optimise quality of care while incurring lower costs and decreasing use of potentially rare resources. Reference Chua, Schwartz, Volerman, Conti and Huang5 Therefore, developing life-long ambulatory practice guidelines that provide both high quality and high value care for patients with CHDs is of paramount importance.

To inform ambulatory practice guidelines, our study sought to delineate current self-reported practice patterns and physician attitudes about factors influencing their testing strategies using vignettes describing common scenarios in the care of patients with tetralogy of Fallot and d-transposition of the great arteries. We also tested the association of physician age with practice patterns. We surveyed a sample of paediatric cardiologists attending a Continuing Medical Education conference and those in a single, large paediatric cardiac centre.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey using two convenience samples of paediatric cardiologists including attendees of a Continuing Medical Educational conference and paediatric cardiologists at a single, large paediatric cardiac centre, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia approved the protocol prior to its initiation.

Study population

We recruited the first sample from attendees at the 2017 annual Continuing Medical Educational conference on paediatric cardiology entitled “Update on Pediatric and Congenital Cardiovascular Disease”. Approximately 300 paediatric cardiologists participate in this conference each year. In its 20th year at the time of the survey, the conference was well established and drew broadly geographically from the United States of America as well as some international attendees. Both university-associated and independent practitioners attend. The second study cohort included 54 board-certified paediatric cardiologists employed by Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, a single academic centre. Physicians in the two cohorts were non-overlapping and they were administered the same survey separately.

Survey design

We developed an online survey explicitly for this study in conjunction with an expert in survey and study design (author JAS). We tested the survey among fellows in paediatric cardiology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for clarity, question content validity, and functionality of the link/site on the electronic survey before sending invites to the two study cohorts. Responses that were collected while testing the survey were not included in the final analysis.

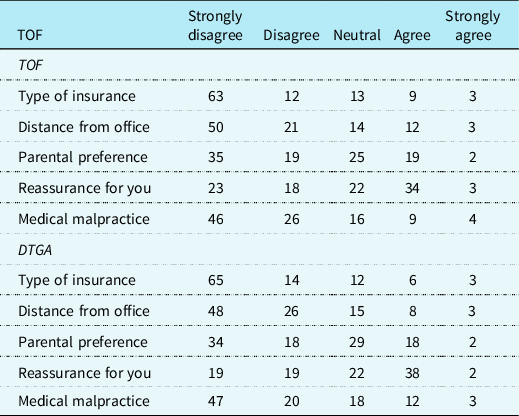

The survey had three components (Supplementary material Table 1). The first component inquired about physician characteristics including practice setting and frequency, date of birth, and years since completing a paediatric cardiology fellowship. The second component elicited self-reported practice patterns to monitor asymptomatic patients by providing vignettes that described common clinical situations, each followed by a series of questions in matrix form to report use of six medical tests [physical exam, electrocardiography, echocardiography, Holter monitors, cardiac MRI and cardiopulmonary exercise testing]. The vignettes were designed to present patients with different disease severity and age. The third component assessed physician age and attitudes towards factors that might influence their decision to order an echocardiogram for an asymptomatic patient with either tetralogy of Fallot or d-transposition of the great arteries, using a 5-point Likert scale. The factors included type of patient insurance, distance from the practice, parental preference, physician reassurance, and medical malpractice. Finally, they were asked about the need for guidelines.

Survey administration

The conference organiser provided the list of attendee emails for the explicit purpose of distributing the survey. A link to the survey with a brief cover letter was distributed through email to all conference attendees and all paediatric cardiology attendings at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The email was sent at 10 days, 1 week, and 2 days prior to the conference, and then 1 week following the conference. The data were directly entered by the respondent via a secured survey link into the Research Electronic Data Capture database housed by the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Only those respondents who reported being a paediatric cardiologist in the first question of the survey were invited to continue the survey.

Statistical Analyses

We display physicians’ responses to the vignettes’ questions in the survey with stacked bar charts and use counts and proportions to show responses to the Likert scale questions. We present the continuous variables of physicians’ age and number of years in practice as a paediatric cardiologist with medians and range. We calculated the Pearson correlation between the physicians’ age and years in practice to determine whether one or both should be used in tests for association with physician practice patterns. To test whether physicians’ self-reported test frequency differed by vignettes of patients with different age and tetralogy of Fallot severity, we performed Skillings–Mack test, Reference Skillings and Mack6 a non-parametric generalised variance test of ratings, on physicians’ responses to the four tetralogy of Fallot vignettes. We assigned numerical values to test frequency (every 6 month = 1, every year = 2, every other year = 3, every few years = 4, every 5 years = 5, and never = 6) and calculated the overall test frequency across the four tetralogy of Fallot vignettes for each physician. The assigned numerical values only reflected the order of test frequency, and we did not assume mathematical linear increase/decrease between adjacent values. Then we ranked physicians by overall test frequency and displayed their consistency of prescribing each test using heat map. We used a dark colour to represent “more frequent tester” and used a light colour to represent “less frequent tester”. Physicians who answered test frequency as “other” or did not provide an answer were assigned a colour of white for that specific question in the heat map. To examine whether physicians’ age was associated with test frequency, we performed univariate regression analysis for each of the six tests in each vignette.

All the analyses were performed using Stata, version 15 (StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.). Tests were two-sided and significance was assessed at an α-level of 0.05.

Results

Study cohort

Of 691 non-Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia affiliated Continuing Medical Educational conference attendees, 213 (31%) reported being a paediatric cardiologist, among whom 97 replied they were practising paediatric cardiologists and were invited to continue the survey. A total of 27 from the 54 invited Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia paediatric cardiologists responded to the survey. The two cohorts were ultimately combined for analysis given that the vast majority (80%) of paediatric cardiologists from the Continuing Medical Educational conference were affiliated with an academic centre and respondents in both cohorts participated in a similar number of outpatient sessions per week. After combining the two cohorts and excluding physicians with partial responses, a total of 110 paediatric cardiologists were included in the analysis. Approximately one-third of respondents reported holding 1–2, 3–5, and >5 outpatient half-day sessions per week.

Reported practice patterns

For each vignette, the frequency with which physicians reported prescribing each of the six different tests is shown in Figure 1. Among 92 physicians who answered all the vignettes, 70–80% physicians reported performing a physical examination and electrocardiography on an annual basis across all vignettes (orange shading). A minority reported performing more or less frequent physical exams and electrocardiographies. Around 65–75% physicians reported performing an echocardiogram on an annual basis across all vignettes, except for teenager patients with d-transposition of the great arteries (56.5% reported performing annual echocardiograms). In the setting of “mild” disease (mild tetralogy of Fallot and d-transposition of the great arteries vignettes) as compared to the physical exam and electrocardiography, 25–35% physicians reported ordering echocardiograms less frequently.

Figure 1. Frequency of physician testing for each modality for six clinical vignettes. Bar chart describing the frequency with which physicians prescribe each test for each of six vignettes is displayed. ( a ) patients with mild TOF, between age of 2 and 12 years; ( b ) patients with mild TOF, between age of 13 and 18 years; ( c ) patients with moderate TOF, between age of 2 and 12 years; ( d ) patients with moderate TOF, between age of 13 and 18 years; ( e ) patients with dTGA, between age of 2 and 12 years; ( f ) patients with dTGA, between age of 13 and 18 years. Frequency of testing is colour coded as detailed in the key ranging from “never” to “every 5 years”. Those responding “other” could not be coded and some failed to reply. Each vignette is represented by one graph.

Overall, other ancillary tests (Holter monitors, cardiopulmonary exercise tests, or cardiac MRIs) were prescribed less frequently than the physical exam, electrocardiography, or echocardiogram (Fig 1). However, physicians were less uniform in their use of these additional tests across all vignettes. In addition, many provided alternative (“other”) prescribing strategies rather than routine surveillance testing.

Individual practice consistency

We display individual level consistency in physicians’ testing patterns in a heat map format (Fig 2). Each physician was categorised as a “more” or “less” frequent tester as compared to the other physicians (x-axis) based on their prescribing patterns in all four tetralogy of Fallot vignettes (y-axis) for each test (panels a–f). Responses for each physician for each vignette are shown moving from less frequent on the left to more frequent on the right. The uniform distribution of colours for the physical exam, electrocardiography, and echocardiogram suggests that individual physicians demonstrate consistent ordering patterns regardless of the vignette (Fig 2a–c). Those ordering these three tests “more” or “less” frequently consistently congregated at either end of the heat map regardless of the vignette; those with the most common practice patterns congregated in the middle. The pattern of individual use was less consistent for the Holter, cardiopulmonary exercise test, or cardiac MRI (Fig 2d–f) represented by the more varied colours or the relative lack of congregation of colours at either end of the heat map. Thus, the use of these latter three tests had both inter-individual variability (Fig 1) and intra-individual variability (Fig 2).

Figure 2. Consistency of physician’s testing frequency for four clinical vignettes. Physicians were ranked by overall testing frequency (high frequency testers towards the right versus low frequency testers towards the left) in the vignettes addressing care for patients with tetralogy of Fallot. Then using heat maps, their consistency of testing was visually displayed across different vignettes for the same modality in each heat map. The frequency of testing was colour coded as noted in the key. MildYoung refers to vignette 2; ModYoung refers to vignette 3; MildTeen refers to vignette 4; ModTeen refers to vignette 5, as detailed in Table 1.

Factors related to ordering practices

We found the majority of physicians disagreed that the patient’s type of insurance, distance from the office, or the threat of medical malpractice influenced practice decisions (Table 2). Some physicians agreed that “parental preference” (20–21%) and “reassurance for the physician” (37–40%) influenced testing patterns.

Table 1. Contents of survey

Table 2. Factors that influence a practitioner’s decision to order an echocardiogram (%)

Physician’s age was not associated with reported testing frequency in older and/or more severely affected patients (p-value > 0.05). However, physician’s age differed significantly between categories of reported testing frequency in the context of younger patients with mild disease (mild, child tetralogy of Fallot: p-value = 0.0007 and child d-transposition of the great arteries: p-value = 0.0094). Specifically, “high frequency” testers were 7.2 (95% CI 3.1, 11.2) years younger than “low frequency” testers in the vignettes of the child with mild tetralogy of Fallot and were 5.1 (95% CI 1.3, 9.0) years younger in the vignettes of the child with mild d-transposition of the great arteries.

A total of 67% responders reported that current testing volume was sufficient as compared to 25% who thought too much testing was performed. Overall, 83% of responders supported the development of outpatient practice guidelines.

Discussion

To date, most clinical guidelines addressing the patient with CHD call upon expert opinion given the lack of data informing best practices. Reference Warnes, Williams and Bashore7–Reference Wernovsky, Lihn and Olen11 Recent attempts to develop metrics by which to standardise care and measure the quality of care have been hampered by the paucity of longitudinal data and at times, the lack of consensus among experts. Reference Villafane, Edwards and Diab10,Reference Wernovsky, Lihn and Olen11 Unfortunately, the absence of evidence-based guidelines can lead to variability in management strategies, costs, and quality of care. Reference Baker-Smith, Carlson and Ettedgui9–Reference Wernovsky, Lihn and Olen11 In one recent study, the authors compared practice patterns to centre-designed standards for the management of the asymptomatic child with a patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect. Reference Ziebell, Ghaleb, Anderson and Statile12 Retrospective chart review identified a significant difference in actual charges as compared to that deemed necessary by their internal standard, highlighting the need to scrutinise practice patterns and define low versus high value testing.

Towards this end, we sought to describe ambulatory practice patterns among paediatric cardiologists. We chose to study tetralogy of Fallot and d-transposition of the great arteries because they represent two common, complex forms of CHDs with excellent peri-operative and long-term results. Reference Jacobs, Mayer and Pasquali13–Reference Khairy, Clair and Fernandes15 Despite this success, many patients experience well-known, associated morbidities and thus undergo life-long monitoring in the ambulatory setting with frequent testing. Relatively familiar and straightforward clinical vignettes that varied by patient age and disease severity were constructed for this survey. We asked only about asymptomatic children over 2 years of age to avoid the immediate peri-operative period.

The vast majority of physicians reported examining post-operative patients on an annual basis with a physical examination, electrocardiography, and echocardiogram. The reported use of additional modalities, including Holter monitors, cardiac MRI, and exercise stress tests, was far more variable. Nonetheless, an important minority reported more frequent or less frequent testing as compared to the majority. Our data also suggest that individual practitioners testing patterns are consistent, falling into either “high”, “common”, or “low” frequency subgroups.

Physician attitudes underlying their reasons for testing varied but many denied ordering tests on the basis of patient insurance, patient distance from the office, or malpractice. Physician age correlated with testing practices but only in the setting of younger patients with mild disease where younger physicians ordered more tests than older physicians. Perhaps younger physicians ordered more tests, in the absence of evidence-based guidelines, because they are less confident in their skills and less familiar with the longitudinal course of patients.

While common, annual visits and testing are not evidence based and as such, not necessarily the “best” strategy. The relationship between more or less frequent testing and clinical outcomes could not be assessed in this survey. However, to devise best practices, the association of practice patterns with long-term outcomes is critical to test in real-life settings and important to understand before developing evidence-based practice strategies. At least one group has suggested a “road map” of less frequent routine testing at particular points of childhood until transitioning to adult CHD care. Reference Wernovsky, Lihn and Olen11 They propose just five comprehensive visits scheduled throughout childhood that provide cardiac and non-cardiac care at natural developmental points. The road map would be modified by reported symptoms or concerns. They point to the necessity of detailing the schedule and setting expectations with the family so they understand from the outset, a life-long plan. Reference Wernovsky, Lihn and Olen11 Such a conversation and plan might alleviate the oft experienced parental anxiety surrounding annual visits to the paediatric cardiologist and may reinforce a culture of health and wellness rather than disease management.

The conclusions that can be drawn from surveys are limited. The results may not be representative of all paediatric cardiologists given the relatively low response rate. In addition, the majority of respondents were affiliated with an academic centre and approximately 25% of respondents derived from a single centre. Thus, physicians from other centres and those in private practice might be underrepresented. As well, the study cohort does not represent all geographic locations or settings equally. Moreover, a survey only reflects recalled rather than actual practices. However, there are currently no guidelines followed by the single centre, whose members practice independently in different clinical settings. More important, the advantage of surveys is that all practitioners respond to the exact same medical vignette in the absence of the well-recognised patient variability that may at times appropriately influence clinical decisions. Indeed, studies have demonstrated the validity of vignettes to isolate physician decision making to assess quality of care delivered. Reference Peabody, Luck and Glassman16–Reference Evans, Roberts and Keeley18 In contrast, detecting and controlling for variable patient characteristics in real-life settings introduces significant challenges while vignettes have demonstrated translation into “real-life” settings. Reference Evans, Roberts and Keeley18 The results of the current survey begin to highlight both the common (i.e. annual visits, electrocardiography, and echocardiograms) and variable (i.e. other modalities) testing patterns but do not provide data supporting one or other strategy.

In order to develop evidence-based guidelines, this work must next be carried into real-life settings. Within paediatric cardiology, work to evaluate the utility of cardiac testing in a limited number of common ambulatory settings has been performed. Extensive studies have tested the appropriateness of performing electrocardiographies, echocardiograms, and exercise stress tests in the setting of an innocent murmur, chest pain, and syncope. Reference Kwiatkowski, Wang and Cnota19–Reference Lu, Bansal and Behera21 Even with data informing practice patterns, implementation of guidelines and adherence to them present additional challenges but are important to pursue to decrease variability in care, minimise expensive low value testing, augment testing where needed, and ultimately optimise the quality of care.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951121004303

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Elizabeth O’Grady for her assistance with survey construction and management.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (United States) and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, revised in 2008, and have been approved by the Internal Review Board of the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.