The use of cardiac pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators has been shown as an effective therapy in children for various arrhythmias, ranging from bradycardic arrhythmias for pacemakers and tachycardic arrhythmias and prevention of sudden cardiac death for implantable cardioverter-defibrillators.Reference Bostwick and Sola1 Despite the rather limited data in children, compared to the adult population, some childhood-specific problems have been revealed by these reports. Due to patient size and the absence of “child-specific” hardware, a great variety of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator and pacemaker implantation routes and techniques are reported. Yet, device-related complications, mainly due to lead failure, have been reported in about 10–44% of children, with the majority of complications occurring in patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator and rather acceptable complication rates in patients with a pacemaker.Reference Eicken2 There are several aspects like coping with the underlying disease, cosmetic aspects (e.g., scars after implantation of cardiac rhythm devices), reciprocating hospitalisation, regular cardiologic follow-up and exercise and behavioural restrictions that are indispensable in the living with an implanted cardiac device. Furthermore, lead-related complications and particularly inappropriate shocks are thought to represent a threat for mental health in children.Reference SILVA3–Reference Korte5 Hitherto studies reported especially preserved consciousness during a shock to be an underestimated burden for the patient as they represent an unpredictable threat that cannot be influenced by the patients themselves.Reference Van Den Broek, Habibović and Pedersen6–Reference DeMaso8

Although some studies picked up this topic during the last years,Reference Bostwick and Sola1–Reference SILVA3,Reference DeMaso8–Reference Pyngottu14 data in children and adolescents still remain scarce. Besides, most studies focused on implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipients rather than children with a pacemaker. Adolescent age, female gender, a higher number of experienced implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks as well as predictability and controlling possibilities of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks, social and family support and personality traits (e.g. tendency to anxiety symptoms) were evaluated as risk factors for the development of mental health problems in children with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators.Reference Bostwick and Sola1 Especially, young adults suffer from a reduced quality of life and increased psychological symptoms after implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation.Reference Eicken2,Reference Thomas7,Reference DeMaso8,Reference Webster11,Reference Hamilton and Carroll15,Reference DeMaso, Neto and Hirshberg16 Women and adolescent girls with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators are affected by anxiety and depression symptoms almost twice as often as men. This seems to result from a negative physical image and aesthetic aspects due to post-operative scars.Reference Sowell17,Reference Walker18 Da Silva et al. published a study that analysed quality of life and physical stamina of children after pacemaker implantation due to congenital atrioventricular block.Reference SILVA3 Children and adolescents with pacemaker implantation due to other cardiac arrhythmias were not included in the study. The study showed reduced mental health as well as reduced vitality and emotional functioning in children after pacemaker implantation.Reference SILVA3 Another study stated that at least 50% of the children with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator show symptoms of anxiety or depression.Reference Eicken2 Besides, the study showed an association between the number of experienced shocks and mental health as well as physical stamina and reduced quality of life.Reference Schron4

The current data relating to this topic are quite inconsistent so that there are even studies that did not show any association between the development of anxiety or depression and implantation of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in children or adolescents.Reference DeMaso8,Reference Leosdottir19 Another study did at least not show any association between the prevalence of depressive symptoms and the treatment with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in children or adolescents.Reference Webster11 Recently, a systemic review of 14 different studies concerning health-related quality of life and psychological adjustment in children and adolescent patients with pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator was published. Overall, the studies indicated that children and adolescents with pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator show a lower quality of life in comparison to healthy peers. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator patients showed more signs of anxiety in comparison to the control group but no differences in occurrence of depressive symptoms in children with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator as well as depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with pacemaker were found. But only 3 of 14 included studies contained data of patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator as well as pacemaker.Reference Pyngottu14 One study also showed no difference in quality of life between children and adolescents with pacemaker in comparison to children and adolescents with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator patients of that study showed higher current and lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in comparison to pacemaker patients and community samples. But higher anxiety rates may not be related to the type of device but to severity of underlying disease and older age at device implantation.Reference Webster11 In summary, there are several studies which analysed mental health and quality of life in children after implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation, but scarce data concerning children after pacemaker implantation and data concerning a comparison between those two device groups.Reference Eicken2,Reference SILVA3,Reference DeMaso8,Reference Sola and Bostwick9,Reference Webster11,Reference Costa12,Reference Pyngottu14,Reference Leosdottir19,Reference Freedenberg, Thomas and Friedmann20 Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate mental health and quality of life in children with cardiac active devices. Specifically, we examined depressive and anxiety symptoms as well as quality of life of children with a pacemaker and with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator and compared these to healthy peers. We expected higher psychological symptoms and lower quality of life in children with cardiac active devices in comparison to healthy peers. We hypothesised that children with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators show a lower quality of life and higher anxiety and depressive symptoms than children after pacemaker implantation. Moreover, we explored the potential effects of gender and age of some aspects in the patient group.

Materials and methods

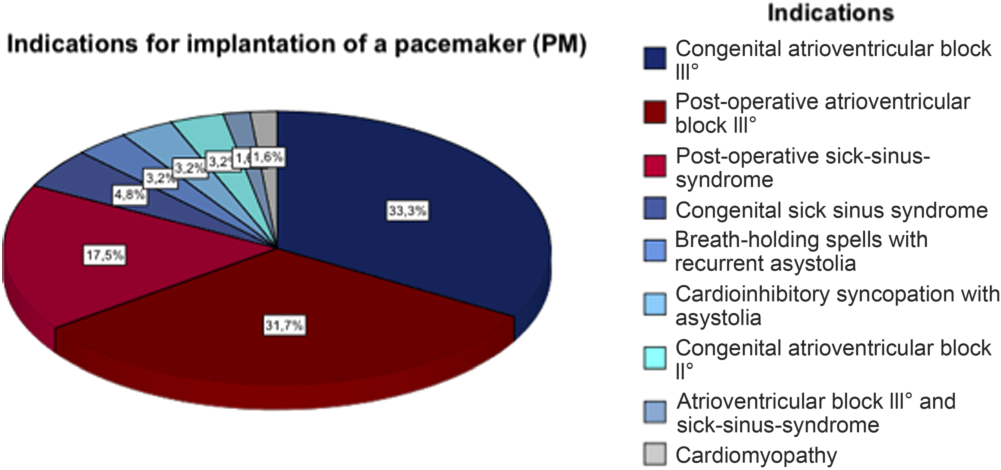

Patients’ recruitment: The patient database of the Heart Centre Leipzig, Department for Paediatric cardiology, was used to recruit patients who received implantation of a cardiac pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Key inclusion criteria comprised the age of 6–18 years, implanted pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, and the absence of exclusion criteria. Indications for cardiac devices were separated into congenital arrhythmias and post-operative arrhythmias. Post-operative arrhythmias were associated with different congenital heart failures and along-going surgeries. The different congenital and post-operative arrhythmias as indications for pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation are each summarised in a circular chart (see Figs 1 and 2). Key exclusion criteria were genetic disorders or syndromes, that are accompanied by mental or physical retardation (e.g. Downʼs syndrome), acute psychosis or being of non-central European origin if they were not able to answer the questionnaires due to barrier of language. Knowledge about mental or physical retardation was collected from medical histories and epicrises. In general, all patients who were not able to understand and answer the questionnaires because of a language barrier or mental problems were excluded from the study. Patients with genetic disorders or syndromes, that are accompanied by mental or physical retardation (e.g., Downʼs syndrome), were excluded because they may have other diseases and impairments due to their syndrome that could affect their quality of life and mental health. Patients with acute exacerbation of psychological diseases were excluded because we assumed that this state of mental health may not correctly reflect their affectation of the cardiac device due to other problems, underlying psychological diseases or even intake of medication, for example, antidepressants or anxiolytics.

Figure 1. Indications for implantation of a pacemaker (PM).

Figure 2. Indications for implantation of an ICD.

Eligible patients and their parents were asked to participate in the study by mail. Demographic data were obtained from all patients at the time of inclusion. All patients and their parents had to give written informed consent. The patients and parents were then respectively asked to fill in a standardised questionnaire for self-assessment (Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC), Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional disorders (SCARED), and Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC-D)) or external assessment (patient history questionnaire, KIDSCREEN-10, CES-DC, and SCARED) of mental health and quality of life.

Quality of life was defined as suggested by the World Health Organization: quality of life refers to an individualʼs perception and subjective evaluation of their health and well-being within their unique cultural environment.Reference Group21

Depressive symptoms are mainly allocated to two important disorders: major depression and dysthymic disorder.Reference Bettge22 These are recurrent unipolar mood disorders which in childhood are phenomenologically equivalent to adulthood, besides some developmental differences.Reference Birmaher23 According to the DSM-IV, the diagnosis of major depression requires a period of depressed mood or irritability for at least 2 weeks in addition to further characteristic symptoms. These may occur in cognition (e.g., poor concentration, feelings of worthlessness and guilt) and/or emotion (e.g., tearfulness, loss of temper, and reduced sense of pleasure or interest). Vegetative symptoms, such as changes in appetite and weight, insomnia or hypersomnia, or changes in motor behaviour (agitation or slowing down) may also occur. Dysthymia in children represents a milder mood disorder with chronically depressed mood or irritability for at least 12 months. Cognitive or vegetative symptoms also may be present, but with lesser severity of symptoms than observed in major depression.Reference Bettge22,Reference Castillo24–26

Anxiety disorder is defined by the World Health Organization as anxiety that is generalised and persistent but not restricted to, or even strongly predominating in, any particular environmental circumstances (i.e., it is “free-floating”). The dominant symptoms are variable but include complaints of persistent nervousness, trembling, muscular tensions, sweating, lightheadedness, palpitations, dizziness, and epigastric discomfort.27

Results from patients with a pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator were compared to a healthy reference sample with the same ethnical and geographical background from the LIFE Child depression study cohort and the BELLA study cohort. In total, 186 children and adolescents filled in the study questionnaires. 136 children and adolescents were patients from the Heart Centre Leipzig, and 50 children and adolescents filled in the questionnaires by participating in the LIFE Child depression cohort.

Results of the patients aged 6–14 years were compared to the results of probands from the LIFE Child depression cohort because this study only included probands aged 8–14 years. To compare data of older patients to an appropriate control group, we cooperated with the BELLA study that also used the CES-DC and the SCARED questionnaire to asses depressive and anxiety symptoms. Children and adolescents participating in the BELLA study were aged 7–17 years, and probands were grouped in children aged 7–10 years and adolescents 11–17 years. The results of the questionnaires were presented separately for the two age groups. Therefore, we used the adolescent group as control group for the results of our adolescent patients.

Reference samples

LIFE Child depression cohort: The LIFE Child study at the LIFE – Leipzig Research Centre for Civilization Diseases – is a longitudinal study to investigate civilisational diseases in probands.Reference Quante28 The LIFE Child study is funded by means of the European Union, by the European Regional Development Fund, and by means of the Free State of Saxony within the framework of the excellence initiative, the German Research Foundation (DFG) for the Clinical Research Centre “Obesity Mechanisms” CRC1052/1 C05, and the Federal Ministry of Education (BMBF).Reference Poulain29 LIFE Child depression cohort encompasses data of 759 healthy children and adolescents as well as peers with health problems inter alia mental health problems, all of them aged 8–14 years.Reference Quante28

BELLA studyReference Ravens-Sieberer30,Reference Ravens-Sieberer31 : The BELLA study is a longitudinal study which investigates developmental trajectories of mental health problems from childhood into adulthood, their determinants, and the utilisation of mental health services. The BELLA study is the mental health module of the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS). BELLA examines the mental health and well-being of children and adolescents aged 11–17 years (a representative subsample of KiGGS, n = 2,863 at baseline).Reference Ravens-Sieberer31

Questionnaires

1. Patient History Questionnaire includes physical health, developmental aspects, family background, and parents’ health.Reference Hölling32–Reference Lange34

2. Child Health Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (KIDSCREEN-10) – parent report for the evaluation of mental health problems in children and adolescents. The tool uses several items that are based on the assumption that quality of life depends on physical, emotional, mental, social, and behavioural aspects.Reference Erhart35,Reference Ravens-Sieberer36 The questionnaire can be used for children and adolescents between 8 and 18 years of age. The questions are rated on a five-point scale.Reference Ravens-Sieberer36 Higher scores indicate a better quality of life, while lower scores indicate a lower quality of life.Reference Ravens-Sieberer37 According to the sum score, patients were categorised into three levels of quality of life – scores of 36 points or less correspond to substandard quality of life, scores of 36–45 points equal average quality of life, and scores higher than 45 points indicate a quality of life above average.

3. Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (Weissman, Orvaschel, & Padian, 1980) – self-report and parent report to assess depressive symptoms in children and adolescents aged 6–17 years.Reference Weissman, Orvaschel and Padian38,Reference Weissman39 The questions are rated on a four-point Likert scale.Reference Barkmann40 A total score of 15 points or higher is classified as clinically relevant depressive symptoms.Reference Fendrich, Weissman and Warner41

4. Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders – self-report and parent report to assess anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents.Reference Birmaher42–Reference Crocetti44 The questionnaire includes five major topics (i.e., panic, unspecific anxiety, separation anxiety, social phobia, and school phobia). The questions are rated on a four-point scale.Reference Birmaher42 A total score of 25 points or higher indicates the presence of symptoms of an anxiety disorder.Reference Birmaher45

5. Self-Perception Profile for Children – self-assessment tool for the evaluation of self-esteem, including five major categories (i.e., scholastic competence, athletic competence, social acceptance, physical appearance, behavioural conduct, and global self-esteem).Reference Muris, Meesters and Fijen46–Reference Harter49 The questionnaire is used for children and adolescents between 8 and 18 years of age.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 21. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the data. Continuous variables are expressed as mean value and categorical variables are given as number of patients (in percentage). The two-sample t-test and Mann–Whitney U-tests were used for the comparison of continuous variables among the groups. The two-sample t-test was used if the distribution of attributes conformed to the Gaussian distribution. Thus, histograms have been generated before statistical analysis was performed. In case of non-existent statistical normal distribution and when comparing small subgroups, the Mann–Whitney U-test was performed. Thence, we used the Mann–Whitney U-test for most of the statistical analyses. Chi-square tests and Fisherʼs exact test were used for the comparison of categorical variables. Results of the patients of the Heart Centre Leipzig were either compared to a reference group of the LIFE study (data of all children under the age of 14 years) by matching each patient with a proband from the LIFE study according to age, gender, and socio-economic status of the children. The socio-economic status was determined through the highest educational or professional qualification of the parents, the highest professional status of the parents, and the equivalised income of the family. The equivalised income was calculated by dividing the net income by the number of persons living in the family. According to the sum score, children were classified into three groups (low, middle, and high socio-economic status). The classification was made according to the values of the KiGGS study.Reference Lampert50

The data of the patients from the Heart Centre Leipzig aged >14 years were compared to published data (mean values and prevalences) from the BELLA study.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

136 children and adolescents participated in the study, including n1 = 86 patients with cardiac active devices from the Heart Centre Leipzig (cardiac pacemaker, n = 63 and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, n = 23 patients).

All of the patients from the Heart Centre Leipzig aged 14 years and younger (subgroup n2 = 50, amongst them n = 40 children with pacemaker and n = 10 children with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator) were matched to healthy peers from the LIFE study as reference group (n3 = 50). Matching of the two groups occurred by means of age, gender, and socio-economic status of the children. As a reference group for patients aged > 14 years (n = 36), we used published data from the BELLA study (n = 1841).

Patients were included if at least two questionnaires were completed.

Table 1 and Table 2 depict the characteristics of the patients from the Heart Centre Leipzig (n1 and n2) and the characteristics of the probands of the LIFE study (n3).

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics of all study participants from Heart Centre Leipzig, furthermore lined up between patients with PM and patients with ICD

ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PM = pacemaker

* Significance level refers to the comparison of patients with PM and patients with ICD.

Table 2. Characteristics of study participants from Heart Centre Leipzig aged ≤ 14 years in comparison to the reference group from the LIFE study

* Significance level refers to the comparison of patients from Heart Centre Leipzig in comparison to the reference group.

Figures 1 and 2 depict the indications for device implantation.

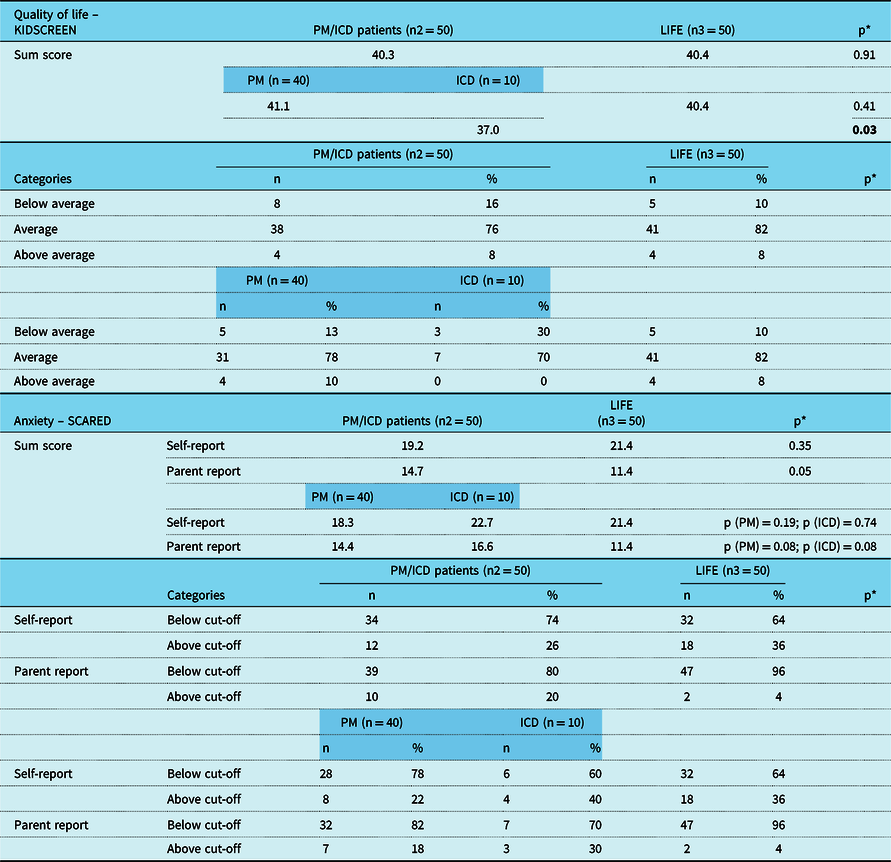

Quality of life

Quality of life was evaluated using the KIDSCREEN-10 questionnaire. There were no significant differences in quality of life when comparing patients with cardiac pacemaker to healthy peers (n3; p = 0.41). However, patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator had a significantly lower quality of life than healthy controls (n3; p = 0.03) (Fig 3). Furthermore, comparing younger children and adolescents from the patient sample (n1), quality of life was independent of age (p = 0.25).

Figure 3. Quality of life (assessed by KIDSCREEN questionnaire) of children and adolescents with PM or ICD in comparison to the reference group.

Anxiety symptoms

Anxiety symptoms were evaluated using the SCARED questionnaire. There were no significant differences in anxiety symptoms when comparing patients with active cardiac devices to healthy peers (self-report: p = 0.05; parent report: p = 0.35). Furthermore, there was no significant difference between children and adolescents with a pacemaker in comparison to children and adolescents with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in self-report (p = 0.53) and parent report (p = 0.77). When analysing the SCARED questionnaire self-report separating male from female patients, boys under the age of 15 years showed significantly higher anxiety symptoms compared to their older peers (p = 0.03).

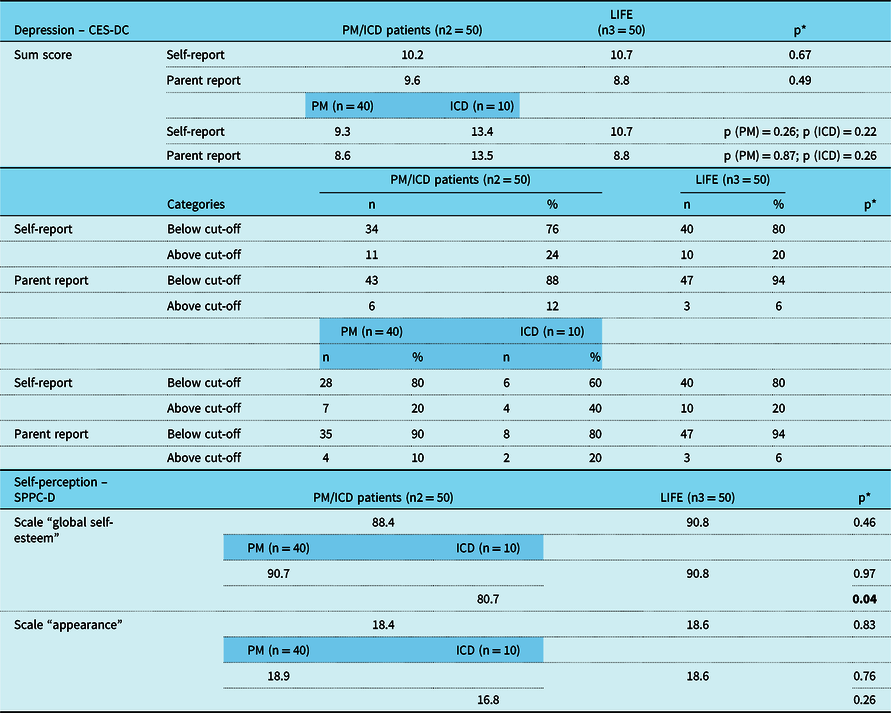

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were evaluated using the CES-DC questionnaire. Up to 25% of patients with a pacemaker or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator showed clinically relevant depressive symptoms, but in comparison to the reference groups, there was no significant difference between children and adolescents with cardiac active devices and healthy peers (parent report: p = 0.49; self-report: p = 0.67). There was no significant difference in depressive symptoms when comparing patients with a pacemaker to those with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (parent report: p = 0.43; self-report: p = 0.86).

Self-perception

Self-esteem was evaluated using the SPPC-D questionnaire. Analysing the subscale “appearance” to assess potential aesthetic aspects caused by the scars in children and adolescents with cardiac active devices, there was no significant difference in the perception of appearance between children and adolescents with pacemaker/implantable cardioverter-defibrillator and healthy peers (p = 0.78). Exploring potential gender effects, female patients with a pacemaker or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator showed a significantly lower physical appearance score compared to male patients with a pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (p = 0.02).

Tables 3–5 depict the results of the questionnaires.

Table 3. Results of all patients from Heart Centre Leipzig, furthermore lined up between patients with PM and patients with ICD.

CES-DC = Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children; ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PM = pacemaker; SCARED = Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional disorders; SPPC-D = Self-Perception Profile for Children.

* Significance level refers to the comparison of patients with PM and patients with ICD.

Table 4. Results of “KIDSCREEN“ and “SCARED“ of study participants from Heart Centre Leipzig aged ≤ 14 years in comparison to reference group from the LIFE study, furthermore lined up between patients with PM and patients with ICD.

ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PM = pacemaker; SCARED = Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional disorders.

* Significance level refers to the comparison of patients from Heart Centre Leipzig in comparison to the reference group, furthermore lined up separately for patients with PM and patients with ICD in comparison to the reference group.

Table 5. Results of “CES-DC“ and “Self-Perception Profile“ of study participants from Heart Centre Leipzig aged ≤ 14 years in comparison to reference group from the LIFE study, furthermore lined up between patients with PM and patients with ICD.

CES-DC = Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children; ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PM = pacemaker; SPPC-D = Self-Perception Profile for Children.

* Significance level refers to the comparison of patients from Heart Centre Leipzig in comparison to the reference group, furthermore lined up separately for patients with PM and patients with ICD in comparison to the reference group.

Self-assessment versus external assessment

Overall, parents descriptively reported lower depressive and anxiety symptoms compared to self-reports of adolescents, but statistically there was no significant difference (SCARED: p = 0.69; CESD-C: p = 0.73).

Discussion

Our study suggests a reduced quality of life in children and adolescents with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Furthermore, data showed only mild tendency towards depressive symptoms in a subgroup of patients, yet, no major depressive symptoms or anxiety were present in the study group. Overall, cardiac pacemakers seem to be less detrimental for the development of psychological problems than implantable cardioverter-defibrillators.

Reviewing literature two things become obvious. First, there is only very little research focusing on children and adolescents, although the number of pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators implanted in children and adolescents grew over the last 20 years.Reference Korte5,Reference Hansky51 Second, there is a relatively large number of publications in adults over the years, mainly focusing on implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipients.Reference Korte5,Reference Botsch52–Reference Newall58 While the early literature seemed to underline the expected higher rate of depressive and anxiety symptoms in adults with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, these findings could not be confirmed in recent studies.Reference Thomas7,Reference Leosdottir19,Reference Godemann55,Reference Newall58 Yet, irrespective of the fact that mental health problems seem to a certain point be a problem in adult patients after implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation, at least an increased quality of life compared to alternative treatment options could be observed in adults treated with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.Reference Schron4,Reference Thomas7,Reference Irvine10,Reference Heller56,Reference Namerow57,Reference Dougherty59

While there is only scarce data in children and adolescents, available reports show a significantly different pattern of mental health problems and quality of life impairments in children and adolescents with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator or pacemaker. As has been reported by DeMaso et al. in 2004, who reported on 44 children with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator that were evaluated concerning their quality of life and mental health, the development of depressive symptoms or anxiety were much less than expected, whereas the quality of life was significantly reduced in their patients collective.Reference DeMaso8 Interestingly, as the quality of life is only the sum of several physical, social, and psychological factors, the study found that negative feelings like depression or anxiety were stronger connected to the patients’ quality of life than expected from known data. The authors supposed that the absence of manifest depression or anxiety might rather be due to the relatively small sample size, and subclinical changes might have been present yet laid beyond the scope of the study.Reference DeMaso8 The findings of our study underline the findings of DeMaso et al., although we also determined a higher amount of children and adolescents above the cut-off score for anxiety and depressive symptoms in comparison to healthy peers without measuring a significant difference. This might be caused by the small number of patients included in the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator group. The small number of patients, especially children and adolescent patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, is one of the critical limits of studies concerning this topic.Reference Eicken2,Reference SILVA3,Reference DeMaso8,Reference Costa12,Reference Schuster13,Reference Freedenberg, Thomas and Friedmann20 The small number of probands might be the reason for the disparate and incongruent results of the studies. A major difference between paediatric and adult collectives in view of the consequences of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation seems to be the different effect on the quality of life which can be improved in adults by adding some kind of a protective or safety aspect but will rather be impaired in children and adolescents. A recently published study gave a review of 14 different publications concerning quality of life and mental health in children with heart failures, arrhythmias, and cardiac devices but only 4 out of 14 studies included children and adolescents with pacemaker as well as implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.Reference Webster11,Reference Pyngottu14,Reference Freedenberg, Thomas and Friedmann20,Reference Czosek60,Reference Czosek61 The majority of those studies showed a lower quality of life and higher prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with cardiac devices in comparison to healthy peers but no difference between quality of life and mental health between patients with pacemaker and patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. This review included a higher number of patients due to analysing 14 different studies, but the number of probands of every single study was partly still very small and the number of patients with pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator was mostly quite dissimilar. Still, the two studies with the highest number of patients yielded the same results regarding quality of life.Reference Webster11,Reference Czosek61 In summary, the review included a lot of different studies with different test methods, different results, different exclusion and inclusion criteria, and high variety of patient samples which limits the comparability of the results.Reference Pyngottu14 In contrast, our study explored that a pacemaker implantation seems to be less detrimental on quality of life or mental health problems. This might be due to the fact that coping with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator or pacemaker in childhood or adolescence includes also the severity of the underlying disease, which is often more critical in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipients and those patients have to cope with the possibility of sudden cardiac death. Data derived from other studies in children and adolescents dealing with other major diseases like epilepsy or cancer showed a relatively low impact of physical impairment on the psychological factors like depression or anxiety. Furthermore, detrimental external factors that affect family function like maternal depression seem to affect the childʼs mental state to a much greater extent. Therefore, the underlying cardiac disease is rather unlikely to affect mental health or therewith quality of life as a single factor.Reference Bostwick and Sola1,Reference DeMaso8 Several variables and risk factors seem to influence mental health of those patients. Among these factors are age (especially, older age at device implantation may increase the risk of anxiety and depressive disordersReference Webster11), female genderReference SILVA3,Reference Costa12,Reference Sears62 , family functioning, and social support as well as the perception of control and predictability of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks. All these factors seem to influence mental health and consequentially quality of life more than just the severity of the cardiac disease.Reference Bostwick and Sola1,Reference DeMaso8 Yet, the sum of the severe underlying disease, the relatively high rate of device-related complications, which has been reported in children and adolescents in up to 40% and the experience of adequate or inadequate shocks will put a great burden on these young patients’ coping mechanisms.Reference Eicken2 Another point that might explain the different consequences of a pacemaker compared to an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator on the childʼs quality of life might be the parental coping with the underlying disease. Anxiety and helplessness will greatly affect the parent–child interaction and will be dependent on the severity of the childʼs underlying disease.Reference Rehm63 Therefore, every option to enhance psychological coping in children with a pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator should also involve parent-directed strategies. In view of supporting strategies for affected patients, an interesting finding of this study was that female patients showed significantly lower self-esteem regarding cosmetic aspects compared to male patients, yet there was no difference in comparison to healthy female peers.

With the goal of an individualised therapeutic offer for patients and their families, the present study supports the strategy already published in other paediatric collectives.Reference Bostwick and Sola1,Reference Eicken2,Reference Van Den Broek, Habibović and Pedersen6,Reference Pyngottu14,Reference Sowell17,Reference Leosdottir19,Reference Freedenberg, Thomas and Friedmann20,Reference Bourke64–Reference Stutts70 Comparison of self-assessment and external assessment in our study showed good external assessments in younger children, while in adolescents symptoms seemed to be reported more often in the self-assessment than the external assessment. Therefore, the parentʼs role for identifying affected patients is rather in the younger children, whereas adolescents should be addressed in a self-assessment protocol.

Conclusion

Living with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in childhood seems to be associated with a lower quality of life in patients compared to healthy controls. In addition, children and adolescents with pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator seem to be at risk to develop mental health problems in a clinical range, especially depressive symptoms. Although the exact reasons for this circumstance remain unclear, treating physicians should be aware of potential mental health problems and provide the patients and their families with appropriate therapeutic offers.

Limitations

After all the findings of this study should be regarded with some caution, as the study collective is still relatively small and there is just a small number of patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Especially, when comparing different subgroups or analysing the data according to gender or age, the comparative groups contain quite a smaller number of probands. Thus, it would be desirable to conduct a multi-centre study to gain more children and adolescents with cardiac devices. Furthermore, the topic of quality of life and perception of mental health, especially depression or anxiety will be dependent on ethnical, regional, and sociocultural aspects. There is a difference between age at implantation, age at assessment and period of follow-up between children and adolescents with pacemaker and their peers with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Especially, the age at implantation and the period of life so far with a cardiac device may influence the quality of life and mental health of the patients. We did not analyse the influence of the underlying congenital heart failure and the effect of the number of cardiac surgeries and other interventions and hospitalisations. Analyses were not made prior to implantation of the device to determine the effect of the implantation. Besides, a longitudinal study could be aimed to analyse changes in the mental health of the patients when becoming an adolescent.

Funding

This publication was supported by the LIFE – Leipzig Research Centre for Civilization Diseases, Universität Leipzig. LIFE is funded by the European Union, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), and the Free State of Saxony within the framework of the Excellence Initiative.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.