As transplantation of the heart is now an established treatment for children with end stage disease, attention is increasingly being focused on the psychological functioning of such young people after transplantation, and on how to maximise quality of life. Low self-esteem, poor social competence, and depressed mood have been identified as particular areas of concern in a significant minority,Reference Wray and Radley-Smith1–Reference DeMaso, Kelley, Bastardi, O’Brien and Blume5 but to date there has been little attempt to look at interventions which might be of psychological benefit to patients, although increasingly the need for such interventions is being acknowledged.

The British Transplant Games are organised by Transplant Sport UK, and are held annually for children and adults who have received transplanted organs, offering both a competitive sporting element and a social element. The event is held over four days, and the majority of children are accompanied by their parents and siblings, staying in hotel accommodation with the rest of their hospital team. Prior to participation in the Games, medical forms have to be completed by the physicians of the participants, based on their most recent clinic visit. Research with adults has suggested that participation is associated with decreased physical symptomatology, and an enhanced body image,Reference McGee and Horgan6 but no evaluation of potential benefits has previously been carried out in children. Children and adolescents from both Harefield and Great Ormond Street Hospitals have been attending the Transplant Games for 10 years or more, with some children attending every year, and anecdotal reports suggest that the event is perceived positively by both children and families. In the absence of any previous structured assessment, we designed a pilot study with the aim of auditing whether participation in such an event had an impact on psychological well-being in the short term for children and adolescents.

Method

All children who had undergone transplantation at Harefield or Great Ormond Street hospitals, were under the age of 18 years, and were at least six months after their transplant, were eligible to attend the Transplant Games and received information about participation. There was no expectation that children would participate and no pressure on them to do so. In all, 28 children attended the Games in 2003. Because of the need to be able to complete the questionnaire, children were eligible for participation in this study if they were at least 7 years old. Parents were asked to consent, and children to assent, to take part in the study.

In the absence of any existing brief measure which would cover the aspects on which we wished to focus, and which would be suitable for children aged from 7 to 17 years, we designed a questionnaire specifically for this study, which was administered on arrival at the Games and just prior to departure, four days later. There were 13 questions, covering areas such as their state of mood, perceived physical health and physical ability, fatigue, anxiety, and confidence. The domains were chosen because of their face validity and relevance to the population and intervention being studied. Questions were all scored on a rating scale of 5 points, and half were reverse scored. We calculated the scores for the individual items, each ranging from 1 to 5, and a total score with a potential range from 13 to 65, with higher scores indicating more positive responses. A rating of the physical health of each child was also made by a clinician, again on a scale of 5 points ranging from 1 for poor to 5 for excellent. Changes over time were analysed by Wilcoxon tests. In addition, young people were asked, informally, how they felt about their participation in the Games, and their answers were recorded verbatim. Qualitative data were subsequently coded and themes abstracted. Anonymised direct quotations have been used to illustrate these themes.

Results

All 26 patients who were eligible agreed to participate. Of the subjects, 7 (27%) were boys, and the mean age of the group was 13.0 years, with a range from 8.3 to 16.9 years. The Games had been attended on one or more previous occasions by 18 of the children. All but one of the patients had undergone transplantation of the heart because of congenital cardiac disease in 5 cases, or cardiomyopathy in the other 20. The remaining patient had undergone transplantation of the heart and lungs because of primary pulmonary hypertension. The procedures had taken place from 13 to 177 months, with a median of 88 months, prior to the Games. In 2 cases the children were unable to compete in all activities due to renal failure, both receiving peritoneal dialysis, while 4 other children had some degree of physical limitation related to a previous stroke, although they competed in all of their chosen events.

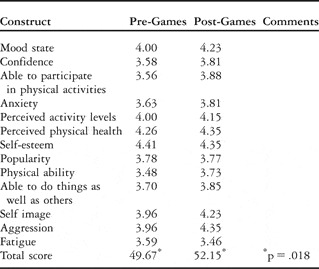

The questionnaire had acceptable reliability, with a Cronbach alpha score of 0.919. There were improvements over time on 10 of the 13 questions, with the change in total score being significant (p = .018) (Table 1). For 5 (19%) children, however, there was a decrease in the total score. Analysis of the responses from these children suggested that the decrease was related primarily to the competitive rather than the social element of the Games. All of the patients reported enjoying the Games, and 23 wanted to return the following year.

Table 1 Mean scores for each construct, and total score before and after the Games.

There were no differences in measures of outcome in terms of gender, initial diagnosis, or treating hospital, but there was a significant correlation between time since transplantation and ratings of physical health before (r = .383; p = .048) and after (r = .470; p = .015) the Games, with longer time since transplantation associated with poorer ratings of physical health. Correlations were also significant between age at the time of the Games, and ratings after the Games of mood (r = .613; p = .001), participation in physical activities (r = .402; p =.042). physical health (r = .393; p = .047), physical ability (r = .439; p = .025), ability to do things as well as others (r = .410; p = .038) and self-image (r = .656; p <. 001), with younger age associated with higher ratings on all of the constructs. Finally, the change in total score was significantly correlated with the rating of physical health given by the clinician, with poorer physical health associated with a greater positive change in total score (r = .648; p = .012).

Analysis of the responses about participating in the Games elicited several themes (Box 1).

Box 1 Themes about participation in the Games

Meeting similar people – “a true peer group”

“Great to meet others who have been through the same stuff and understand what it is like – then you don’t have to explain anything.”

Increased self confidence

“I feel much more confident and able to do things and I am not so worried about everything any more.”

Hope for the future

“Although I only recently got my transplant I saw people running who had theirs more than 10 years ago! That was brilliant – realising that you can do all those things years later.”

Dislike of competitive element

“I didn’t like the running and stuff but I enjoyed meeting other people like me”.

Discussion

For the majority of children and adolescents, participation in the British Transplant Games was associated in the short term with positive changes in psychological well-being. The young people showing the greatest positive change were those with some degree of physical difficulty. They particularly endorsed the themes of improved confidence, and the sense of belonging to a peer group. Some of these young people were socially isolated in their home environment, and were unable to participate in the lifestyle of their healthy peers, but being with other young people who had similar difficulties helped to empower them. In contrast, five patients showed a decrease in total score, four of whom were teenage girls who did not like competing, and felt self-conscious in front of others.

After the Games, younger children rated themselves more positively than older children on a number of constructs, which may be related to the fact that they were given the opportunity to be independent, and were able to participate in activities in which perhaps they had not been previously allowed to take part. It has been suggested that children who have received transplanted hearts do not participate in sufficient physical activity, possibly due to over-protective parents and a lack of supervised facilities.Reference Pastore, Turchetta and Attias7 This may be particularly true for younger children. The domain showing the area of greatest improvement was perceived level of aggression, which has potential significance for longer term psychological functioning and adherence, as anger has been shown to be associated with non-adherence in other groups of adolescent recipients.Reference Penkower, Dew, Ellis, Sereika, Kitutu and Shapiro8

Our pilot study utilised a measure which has not been previously validated, and for which there are no normative data. The questionnaire did not enable us specifically to identify which aspects of participation were important. The small sample, and short period of follow-up, also limits the generalisability of our findings. Furthermore, this is a self-selected sample. It is possible that those patients who choose to participate in events such as the Transplant Games are more likely to believe that they will benefit, and be more willing to engage in the process. Some who choose to participate may also be those young people who have fewer difficulties in adjusting, and who are therefore less likely to show positive changes over time, which is supported by the fact that a number had high scores both before and after participation. It is encouraging, nonetheless, that a number of participants with problems with physical health also chose to attend the event. Positive results may also be due to the sense of belonging to a “true peer group”, although it is difficult at this stage to tease out such elements.

This is one of the few reported non-medical interventions for children subsequent to transplantation, and highlights the need for further evaluation to determine whether such benefits are maintained in the longer term. Each year greater numbers of children participate in the Games. Future follow-up is planned with a bigger sample size, and to include children who have been transplanted in other centres. Participation in the Transplant Games is medically contraindicated for very few patients. Clinicians, therefore, have an important role to play in encouraging participation, particularly for younger patients, thus reassuring patients and families that it is “safe” for children to take part. Other interventions, and in particular those of a non-competitive nature, for reducing psychological morbidity also need to be identified and evaluated. Whilst competitive sport has its place for helping teach children some important skills with regard to coping, negotiating, and leadership, this may not be the best environment for children and adolescents who are already identified to be struggling from a psychological perspective. With this in mind, “challenge via individual choice” is a much more powerful tool, and our data support initiatives which are focused on inclusion of young people, and particularly those who are in the adolescent age range, in such activities.