A mirror-image of the aortic arch without concomitant cardiac abnormalities, also called a solitary right aortic arch, is extremely unusual.Reference D’Cruz, Cantez, Namin, Licata and Hastreiter 1 – Reference McElhinney, Hoydu, Gaynor, Spray, Goldmuntz and Weinberg 4 In this context, the mirror-image does not indicate the part of the situs inversus caused by dysfunction of gene cascades that determine the left/right axis and accompany several heart anomalies such as the apex being directed rightward.Reference Mano, Adachi, Murakami, Yokoyama and Dodo 5 In the solitary right aortic arch, two types of the ductus arteriosus and their corresponding ligaments have been described. McElhinney et alReference McElhinney, Hoydu, Gaynor, Spray, Goldmuntz and Weinberg 4 termed them the right-sided and left-sided ductus arteriosus, respectively. The left-sided ductus communicates between the “left” subclavian and the pulmonary arteries in a frontal plane ventral to the trachea and oesophagus.Reference McElhinney, Hoydu, Gaynor, Spray, Goldmuntz and Weinberg 4 , Reference Bhatnager, Wagner, Kuwabara, Nettleton and Campbell 6 – Reference Ng, Thavendiranathan, Crean, Li and Deva 10 In contrast, the right-sided ductus connects to the descending aorta and the “left” pulmonary artery “behind the oesophagus”.Reference Schlesingner, Mendeloff, Sharkey and Spray 11 – Reference Bhat, Girish, Mahimarangaiah and Manjunath 19 Furthermore, these two types of ductus are likely to coexist.Reference Abe, Isobe and Atsumi 20 , Reference Bronshtein, Zimmer, Blazer and Blumenfeld 21

Recently, we had a patient with asymptomatic solitary right aortic arch, although she expired due to acute renal failure at 96 years of age in March, 2015 (data not published). According to the radiology images, we have provided a schematic drawing in Figure 1 to show the patient’s anatomy including the right-sided ductus arteriosus, strictly the ligamentum arteriosum. The ascending aorta arose from the left ventricle, crossed the ventral side of the right pulmonary artery, and on the right side of the second thoracic vertebral body it curved posteriorly to provide an acute downward arch continuing into the descending aorta. The trachea and oesophagus showed significant curvature and they were sandwiched together by the ascending aorta and the descending aorta. The left brachiocephalic artery, the right common carotid artery, and subclavian arteries originated in the same order from the top of the aortic arch. These rare morphologies, especially the right-sided ductus, strongly forced us to study the embryology of these aspects.

Figure 1 Schematic representation of our patient’s case. The aortic arch issues the left brachiocephalic artery (star), the right common carotid artery (rtCCA), and the right subclavian artery (rtSCA) in the mentioned order. The trachea and oesophagus (ES) together take significant curved courses and both the structures are present into a narrow space surrounding the aortic arch. A straight band (arrowhead) was identified as a most likely candidate of the ligamentum arteriosum connecting between the left pulmonary artery (ltPA) and the descending aorta (DE) in the posterior side of the ES. AA=ascending aorta; AZ=azygos vein; ltCCA=left common carotid artery; ltSCA=left subclavian artery; LV=left ventricle; rtPA=right pulmonary artery; RV=right ventricle; SVC=superior caval vein.

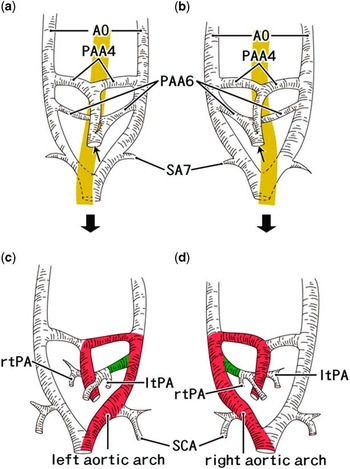

In contrast to normal development (Fig 2a and c), inversion of the left/right axis – that is situs inversus – at 5–6 weeks of gestation is characterised by the connection of the fourth pharyngeal arch arteries to the heart tube on the left side of the connection of the sixth pharyngeal arch arteries (Fig 2b). In both normal and inverted developments, the seventh or the eighth segmental arteries and a union of the bilateral dorsal aortae are seen on the far caudal or distal side of these pharyngeal arch arteries.Reference Barry 22 – Reference Koizumi, Homma and Sakai 25 Thus, at 7 weeks of gestation, the inverted ductus arteriosus seems to merge with the right embryonic aortic arch on the proximal side of the origin of the subclavian artery (Fig 2d). As it is derived from the pharyngeal arch artery, the ductus should be located on the ventral side of the trachea and oesophagus. Therefore, the right-sided ductus behind the oesophagus (Fig 1) is unlikely to originate from the pharyngeal arch artery. The ductus from the right pulmonary artery, as seen in the inversion, is absent in the case of solitary right aortic arch.Reference McElhinney, Hoydu, Gaynor, Spray, Goldmuntz and Weinberg 4 Consequently, using serial embryonic sections, the aim of this study was to provide better understanding of the pathogenesis of solitary right aortic arch, especially with the right-sided ductus.

Figure 2 Schematic explanations of the early development of the aortic arch according to our recent studies. Classical diagramsReference Barry 22 are modified by our recent observations.Reference Naito, Yu, Kim, Rodriguez-Vazquez, Murakami and Cho 23 , Reference Yamamoto, Honkura and Rodríguez-Vázquez 24 The left-hand side of the figure corresponds to the right side of the body. Fetal morphology is shown at 5–6 weeks ( a and b ) and 6–7 weeks ( c and d ). Panels ( a and c ) exhibit the normal development, whereas panels ( b and d ) represent the inverted morphology. The yellow colour belt in panels ( a and b ) indicates the pharynx and the oesophagus: the union of the bilateral dorsal aortae (AO) is located behind the oesophagus. Asymmetrical morphology of the fourth and sixth pharyngeal arch arteries (PAA4, PAA6) are established at an initial stage, including a common outflow trunk of the heart (arrow). The seventh segmental artery (SA7) as well as the aortic union is actually much more caudal than that shown in this diagram as the vertebral segment and the pharyngeal arch are quite different. In panels ( c and d ), the red colour zone indicates the aortic arch, whereas the green colour zone indicates the future ductus arteriosus. The dysfunction in gene cascades that control the systemic left/right axis provides “both” of the right-sided aortic arch and the inverted outflow tracts of the heart. ltPA=left pulmonary artery; rtPA=right pulmonary artery; SCA=subclavian artery.

Materials and methods

The study was carried out in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki 1995 – as revised in Edinburgh in 2000. The embryonic and fetal sections were from the large collection maintained at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. The specimens in the collection were products of miscarriages and ectopic pregnancies managed at the university. We utilised serial horizontal sections of 15 embryos of crown–rump length 6–14 mm, of ~5–6 weeks of gestation and Carnegie stage 15–16, as well as serial sagittal sections of 10 specimens of crown–rump length 28–40 mm, of ~8–9 weeks of gestation and Carnegie stage 22–23. All the sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin or silver stain. The study protocol was approved by the university ethics committee (No. B08/374).

Results

Horizontal sections of all 15 embryonic specimens of gestational age 5–6 weeks consistently showed both the left and right embryonic aortic arches (Figs 3–5), although three larger specimens – of crown–rump lengths 12, 13.6, and 14 mm – showed the process of closure of the right arch (Fig 5). The dorsal aortae were present on the far posterior side of the fourth and sixth pharyngeal arch arteries. Left/right symmetry of the fourth pharyngeal arteries was present in the midline of the bulbus cordis – the initial outflow tracts – of the smallest specimen (crown–rump length 6 mm; Fig 3), but the left sixth pharyngeal arch artery – that is, a future ductus arteriosus – was consistently thicker than the right sixth pharyngeal arch artery in the bulbus. Thus, the left/right difference had already been established in the bulbus cordis at 5 weeks of gestation. Moreover, the laterality of the ductus was established in combination with the left/right difference in the heart. No arteries crossed the posterior aspect of the trachea and oesophagus.

Figure 3 The sixth pharyngeal arch artery (PAA6) or the future ductus arteriosus establishes the left/right asymmetry much earlier than the disappearance of the right aortic arch. Normal development. The smallest specimen of the embryos examined (crown–rump length 6 mm, 5 weeks). The left-hand side of the figure corresponds to the right side of the body. Tilted horizontal sections. Haematoxylin and eosin staining. Panels ( a or j ) displays the most cranial or caudal site in the figure. Intervals between panels are 0.4 mm ( a – b ), 0.1 mm ( b – c , c – d , d – e , e – f , f – g ), 1.0 mm ( g – h ), and 0.1 mm ( h – i , i – j ), respectively. The fourth pharyngeal arch arteries (PAA4) show symmetrical configuration and, after joining between the bilateral ones, the artery occupies in midline in the bulbus cordis ( d and e ). In contrast, the PAA6 takes asymmetrical configuration: the left one (a future ductus arteriosus) was thick ( g ). The bilateral segmental arteries ( j ) (candidates of the subclavian arteries) originate from the union of the bilateral dorsal aortae (AO). Sympathetic ganglia (arrows) developing near the courses of the AO. All the panels are prepared at the same magnification ( a : scale bar, 1 mm). AR=arytenoid swelling; BP=brachial (nerve) plexus; BR=bronchus; CCV=common cardinal vein; ES=oesophagus; ltAO=left AO; ltAU=left auricle of the atrium; NC=notochord; NG=nodosa ganglion; PC=pericardium; PG=pharyngeal groove of the ectoderm; PH=pharynx; PP2=second pharyngeal pouch; PP3=third pharyngeal pouch; PP4=fourth pharyngeal pouch; Rathke=Rathke’s pouch; rtAO=right AO; rtAU=right auricle of the atrium; ST=stomodeum (initial mouth).

Figure 4 An anomalous midline ganglion is likely to push the distal-most part of the aortic arch at 5 weeks. Crown–rump length 10 mm (a variant). Tilted horizontal sections. Haematoxylin and eosin staining. The left-hand side of the figure corresponds to the right side of the body. Panels ( a or h ) displays the most cranial or caudal site in the figure. Panel ( i ) is a higher-magnification view of the central part of panel ( f ). Intervals between the panels are 0.5 mm ( a – b ), 0.2 mm ( b – c , c – d ), 1.0 mm ( d – e ), 0.8 mm ( e – f ), and 0.1 mm ( f – g , g – h ), respectively. In panels ( c and d ), both the fourth and the sixth pharyngeal arch arteries (PAA4, PAA6) show asymmetrical configuration: the left sixth artery is well developed (a future ductus arteriosus). Sympathetic ganglia (arrows) are developing near the courses of the dorsal aortae (AO). In panel ( f ), an abnormal, midline ganglion (arrowhead) is seen between the bilateral AO in the 0.2 mm cranial side of the aortic union. The bilateral segmental arteries (SA) provide proximal parts of the subclavian artery ( g ). Panel ( i ) is a higher magnification view of the midline ganglion (scale bar, 0.1 mm). Panels a – h are prepared at the same magnification ( h : scale bar, 1 mm). AR=arytenoid swelling; BP=brachial (nerve) plexus; CCV=common cardinal vein; COT=common outflow tract in the bulbus cordis; DRG=dorsal root ganglion of the spinal cord; ES=oesophagus; L=liver; ltAO=left AO; ltAU=left auricle of the atrium; ltBR=left bronchus; ltCCV=left common cardinal vein; ltSCA=left subclavian artery; NC=notochord; PA=pulmonary artery; PH=pharynx; PP2=second pharyngeal pouch; PP3=third pharyngeal pouch; PV=pulmonary vein; RA=right atrium; rtAO=right AO; rtAU=right auricle of the atrium; rtSCA=right subclavian artery; ST=stomodeum (initial mouth); TR=trachea; V=common ventricle.

Figure 5 Closure of the right aortic arch starts before the caudal migration of the left subclavian artery (ltSCA) along the left arch. Normal development. Crown–rump length 13.6 mm. Horizontal sections. Haematoxylin and eosin staining. The left-hand side of the figure corresponds to the right side of the body. Panels ( a or g ) displays the most cranial or caudal site in the figure. Intervals between the panels are 0.2 mm ( a – b ), 1.3 mm ( b – c ), and 0.1 mm ( c – d , d – e , e – f , f – g ), respectively. The left dorsal aorta (ltAO) suddenly increases in thickness below the level of connection with the sixth pharyngeal arch artery (PAA6) or a future ductus arteriosus ( a and b ). In contrast, the right aorta (rtAO) decreases in thickness ( b and c ) and closes (arrowhead in panels ( d and e )), but it appears to re-open at the union with the left aorta (arrowhead in panel ( f )). Arrows indicate sympathetic ganglia near the subclavian artery and aortae. Below the union of the aortae, a fibrous tissue is connected between a right-sided ganglion and the aorta (arrowheads in panel ( g )). Asterisks in each of the panels ( a – d ) indicate tissue damage during the histological procedure. All the panels are prepared at the same magnification ( g : scale bar, 1 mm). BP=brachial (nerve) plexus; BR=bronchus; CCV=common cardinal vein; COT=common outflow tract in the bulbus cordis; ES=oesophagus; NC=notochord; PA=pulmonary artery; PAA4=fourth pharyngeal arch artery; PC=pericardium; PH=pharynx; rtAU=right auricle of the atrium; rtSCA=right subclavian artery; SA=segmental artery; TR=trachea; VN=vagus nerve.

The courses of the left and right embryonic aortic arches were straight downward, not curved as shown in textbooks (Fig 2), immediately on the ventral side of the paravertebral sympathetic ganglia. These arches joined along the midline at the level of the head of the first rib or just above the tracheal bifurcation. A single specimen, of crown–rump length 10 mm (Fig 4), showed a large ganglion at the midline close to the union of the arches. Segmental arteries branched off both the embryonic aortic arches towards the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord; one of these arteries had a thick branch running ventrally to the brachial nerve plexus – that is, the subclavian artery – at the level of or below the tracheal bifurcation (Figs 4g and 5). The sympathetic ganglia often attached to the subclavian arterial origin from a segmental artery; three or four pairs of segmental arteries were seen between the sixth pharyngeal artery and the subclavian artery. In the larger three specimens showing connections between the thick left sixth pharyngeal arch artery and the left dorsal aorta, the right embryonic aortic arch diminished in thickness at sites both proximal and distal to the origin of the subclavian artery (Fig 5b and c). The closed distal part of the right aorta provided a site for cell condensation or a fibrous structure (Fig 5e and g). Therefore, the disappearance of the right aortic arch occurred much later than the establishment of the heart and ductus, but it started before the caudal migration of the ductus or sixth pharyngeal arch artery.

Sagittal sections of all the 10 specimens of gestational age 8–9 weeks showed that the ductus arteriosus connected the descending aorta “distal” to the origin of the left subclavian artery, indicating that the caudal migration of the aortic attachment of the ductus had been completed (Fig 6). Thus, the left subclavian artery and the ductus had been reversed in proximodistal position of their aortic attachments. The long distance between the ductus arteriosus and subclavian artery at 5–6 weeks of gestation – that is, 3–4 vertebral segments (Fig 6) – had been reduced into a height of a single vertebral body (Fig 6f and g). The ductus arteriosus was always as thick as the descending aorta, showing a straight superoposterior course to a site immediately to the left side of the oesophagus. The embryonic right aortic arch was absent in all the 10 specimens. A posteriorly curved trachea was present in a single specimen of crown–rump length 36 mm, with the curve likely due to the brachiocephalic artery originating in front of the trachea (Fig 6a and b). The course of the ductus arteriosus in this specimen was straight, almost along the midline towards the trachea, with the ductus arteriosus attaching to the aorta in a more rightward position than usual. At 8–9 weeks of gestation, the posterior extension of the pleural cavity was not yet evident, but the thyroid, thymus, and aortic arch were restricted within a relatively small area, with a height almost four times the diameter of the ascending aorta.

Figure 6 A fetus with a significant posterior flexure of the trachea (TR) in relation with a slight positional change of the ductus arteriosus. Crown–rump length 36 mm (a variant). Sagittal sections. Haematoxylin and eosin staining. Panels ( a or g ) displays the most right or left site in the figure. Intervals between the panels are 0.8 mm ( a – b ), 0.4 mm ( b – c ), 0.5 mm ( c – d ), 0.4 mm ( d – e, e – f ), and 0.2 mm ( f – g ), respectively. The brachiocephalic artery (BA) and right subclavian artery (rtSCA) attach to the posterior flexure of the TR ( a and b ). The ductus arteriosus (DA) does not pass the left side of the TR but directs towards the ventral aspect of the TR (i.e. an almost midline course ( d )). The left common carotid artery (ltCCA) takes a highly tortuous course ( d – g ). The origin of the left subclavian artery (ltSCA) is found in the final position immediately proximal to that of the ductus ( f and g ). All panels are prepared at the same magnification ( a : scale bar, 1 mm). AA=ascending aorta; A valve=aortic valve of the heart; BR=bronchus; CC=cricoid cartilage; DE=descending aorta; ES=oesophagus; LA=left atrium; ltPA=left pulmonary artery; LV=left ventricle; PV=pulmonary vein; rtlung=right lung; rtPA=right pulmonary artery; RV=right ventricle; TH=thymus; TY=thyroid gland.

Consequently, the sequence of developmental events at and around the ductus arteriosus were ensured as follows: (1) the establishment of the left/right difference in both the “heart and ductus”, (2) the disappearance of the right aortic arch, (3) the drastic caudal migration of the ductus along the left aortic arch, and (4) a positional effect of the great arteries to provide variations in the trachea and oesophagus. Development of the sympathetic ganglia along the aortic arches occurred at and before the aforementioned step 2. In all the steps, with an exception at the distal-most part of the left or right aortic arch, no artery crossed behind the oesophagus and pharynx.

Discussion

In the present study, according to McElhinney et al,Reference McElhinney, Hoydu, Gaynor, Spray, Goldmuntz and Weinberg 4 we used the term “right-sided ductus arteriosus” for an artery connecting between the descending aorta and the left pulmonary artery behind the oesophagus (see the introduction). At the beginning of this study, we thought that the right aortic arch in combination with the right-sided ductus would require the fourth and the sixth pharyngeal arch arteries in the bulbus cordis to be inverted; however, examination of the 5- to 6-week-old specimens showed that the left/right asymmetry of the fourth and sixth pharyngeal arch arteries was established together with the determination of laterality of the heart. Conversely, without inversion, the ductus or the sixth pharyngeal arch artery was unlikely to connect to the right pulmonary artery.

Developing sympathetic nerve ganglia were observed immediately posterior to the bilateral embryonic aortae. The most striking finding in the present study was a large midline ganglion pushing the union of the aortic arches; this suggested a mass effect to cause anomalies of the great arteries. This rare variation, if shifted leftward (Fig 7a and b), could interrupt blood flow through the left aortic arch, causing the anatomic anomaly seen in our patient (Fig 1). The ductus seemed to steal the distal left arch with the aid of obstructive mechanical stress from a variant ganglion to provide the right-sided ductus far distal to the origin of the left brachiocephalic artery. When the ganglion pushes the distal end of the left aortic arch, the sixth pharyngeal arch artery can continue to the proximal part of the left arch to provide the left-sided ductus ending at the left brachiocephalic or subclavian artery. In fact, variations in cardiac nerves have been reported in a cadaver with a retro-oesophageal right subclavian arteryReference Horiguchi, Yamada and Uchiyama 26 as well as with solitary right aortic arch.Reference Koizumi, Homma and Sakai 25 , Reference Konishi and Kikuchi 27

Figure 7 A diagram showing our hypothesis to explain the pathogenesis of solitary right aortic arch in the present patient. The left-hand side of the figure corresponds to the right side of the body. In panel ( a ), the oesophagus (yellow) has already curved due to a slight shift of the left sixth pharyngeal artery. Drastic migration of attachments to the aorta occurs for the ductus arteriosus and subclavian arteries (arrows). An aberrant sympathetic ganglion (GL) pushes the distal part of the left embryonic aorta to close it. As a segmental artery supplies mainly the dorsal root ganglion (DRG), it unlikely issues a retro-oesophageal branch (?). In panel ( b ), the ductus arteriosus, after migration, steals the distal part of the left aortic arch (blue) and, depending on rapidly altered topographical relation, the ductus changes the direction to maintain a shortcut course between the left pulmonary artery and the right aortic arch (red).

In a single fetus, we found a posteriorly curved trachea due to the leftward shift of the origin of the brachiocephalic artery in front of the trachea. In that specimen, the ductus arteriosus took a straight superoposterior course almost along the midline towards the trachea, perhaps causing the aortic attachment to be more distal than usual. In our patient (Fig 1), the left (normal) sixth pharyngeal arch artery may have also developed along or near the midline; however, due to subsequent closure of the left aortic arch by a mass effect of the ganglion variant, the ductus may have used the distal end of the left arch to maintain the shortcut flow to the right aortic arch (Fig 7). A slight positional change of the great arteries in embryos seem to cause distinct variations in the surrounding structures such as the trachea and the oesophagus.

According to the present observations, the aortic attachment of the ductus arteriosus migrated far caudally to a site distal to the subclavian arterial origin at and around 7 weeks of gestation. According to our additional observations (unpublished data), in specimens larger than crown–rump length 23 mm (7 weeks), the aortic attachment of the ductus was consistently located distal to the left subclavian arterial origin. An increased blood flow through the ductus arteriosus requires a shortcut course from the ductus to the descending aorta and it seemed to accelerate the changing in sites of aortic attachments. In addition, the pharyngeal arch arteries never run between the oesophagus and the trachea or behind the oesophagus. In contrast, there are two groups of arteries passing posterior to the oesophagus: segmental arteries and distal ends of the bilateral aortic arches. As the segmental arteries supply largely to the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, their branch was unlikely to provide a retro-oesophageal communication (Fig 7a).

In both the embryonic and the fetal specimens (at 5–6 weeks and at 8–9 weeks), the bilateral aortic arches joined just above the tracheal bifurcation, but the vertebral levels were different between the two groups. The aortic arches and ductus arteriosus, as well as the tracheal bifurcation, appeared to descend depending on the descent of the heart as well as the growth of the vertebral column. In our patient (Fig 1), a superoinferior level of the union of the embryonic bilateral aortic arches – that is, the height of the right-sided ductus – seemed to correspond to the third-fifth vertebral body in adults. Notably, most of the so-called “arterial ring”Reference Bronshtein, Zimmer, Blazer and Blumenfeld 21 , Reference Kasai, Aiyama, Kihara and Takahashi 28 is formed in the same level. The arterial ring seems to follow a pathogenesis similar to the solitary right aortic arch – that is, a sequence of the distal migration of aortic attachment of the ductus, obstructive stress, and steal of a part of the unilateral aortic arch. In addition, although there seems to be a difference between human and rat anatomy,Reference Aizawa, Isogai, Izumiyama and Horiguchi 29 we observed the subclavian artery originating from a segmental artery at a level immediately cranial to the union of the bilateral embryonic aortae in our specimens as well.

Consequently, the solitary right aortic arch is not a partial or incomplete type of situs inversus, but rather results from a combination of multiple variations occurring at 5–7 weeks of gestation. We believe that Figures 4 and 6 demonstrate the most likely examples of the variations in embryos and fetuses. Depending on timing and site of the obstruction of the left aortic arch by a mass effect of the sympathetic ganglion, the right-sided ductus, the left-sided ductus, or both seemed to be likely to connect with the left pulmonary artery.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the mothers who donated their babies after death to Complutense University for research without any economic benefit.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all the procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1995, as revised in 2000, and has been approved by the institutional ethics committees (No. B08/374).