Marfan syndrome was first described by a French paediatrician Antoine Marfan in 1896.Reference Gott 1 It is an autosomal dominant connective tissue disorder in which abnormalities primarily occur in the cardiovascular, skeletal, ocular, and pulmonary systems. The prevalence of Marfan syndrome is approximately two to three per 10,000 individuals and it is caused by a mutation in the fibrillin-1 gene (FBN1) located on chromosome 15q21.1.Reference Pyeritz 2 The neonatal Marfan syndrome presents with a rare and severe phenotype early in childhood. We describe a case of neonatal Marfan syndrome diagnosed because of a presumed positive family history, dysmorphic features, and cardiac abnormality, which lead to genetic evaluation. Molecular genetic studies showed a mutation in exon 31 of the FBN1 gene in both the patient and his father.

Case report

The patient was referred for genetic evaluation at 2 months of age because of aortic root dilation observed on an echocardiogram performed at the age of one month. The patient's father had presumed diagnosis of Marfan syndrome. The infant was asymptomatic, feeding well, and gaining weight appropriately.

The patient was born to a 24-year-old G3P2 mother after a term uncomplicated pregnancy. At birth his weight was 3200 g (25th percentile) and length was 51 cm (>50th percentile). He was the father's first child. Both parents were Hispanic and consanguinity was denied.

The patient's father, 28 years old, was 177.8 cm in height, which was normal for his family, with a prominent protruding forehead and large prominent ears. His fingers were stiff, and wrist and thumb signs were negative. He attended special education in school and reported vision problems with multiple eye surgeries and a surgical history of aortic valve replacement. He had never been tested for Marfan syndrome and was told he probably had this condition. He denied any family history of a tall stature, sudden death, or cardiac surgery. The patient's mother was healthy and her two children from a previous relationship were alive and well.

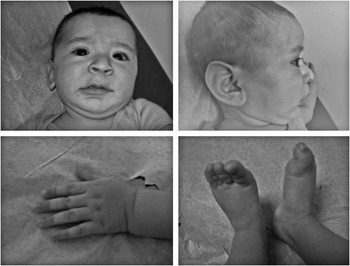

Physical examination on the infant revealed dysmorphic facies, micrognathia, a high arched palate, long (>97th percentile) protruding ears, and arachnodactyly (Fig 1). His extremities and joints were normal without any hyperextensibility or contractures. No cardiac murmur was noticed. His abdominal exam was normal and genitalia showed an uncircumcised penis with undescended testes. The ophthalmologic exam was unremarkable and ectopia lentis was not detected.

Figure 1 The proband with typical features of neonatal Marfan syndrome: downslanting palpebral fissures, micrognathia, large ears, and arachnodactyly.

An echocardiography performed at 3 months of age showed an aortic root dilatation that measured 1.67 cm (Z = 3.4). The mitral valve appeared thickened without prolapse or regurgitation. No other valve regurgitation was observed. In view of the cardiac abnormality, together with the unusual physical appearance and family history, neonatal Marfan syndrome was suspected and blood for genetic testing was obtained from the patient and his father.

Molecular genetic studies

Sequencing of the FBN1 gene in the patient and his father showed a heterozygous c.3959G > A transition in exon 31. This mutation converts a codon for a conserved cysteine (TGT) into a codon for tyrosine (TAT) in calcium-binding epidermal growth factor-like domain 17.

Clinical course and treatment

The patient was started on losartan, angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, and propranolol, which is a β-blocker, at the age of 3 months with close blood pressure monitoring. The initial oral dose of losartan was 0.6 mg/kg/day, which was gradually increased to a maximum of 1.4 mg/kg/day. The renal function was normal before starting the treatment and after 3 months of therapy. The patient remained asymptomatic during follow-up. Serial echocardiograms showed stable aortic root dilatation, as shown in Table 1 and Fig 2.

Table 1 Sinus of Valsalva diameters during follow-up.

Figure 2 Transthoracic echocardiogram studies in the parasternal long-axis view showing the aortic root diameter at 3 months of age (upper frame) and at 9 months of age (lower frame) measured during systole.

Discussion

We report the clinical data of a male infant with neonatal Marfan syndrome who has a fibrillin-1 mutation that was transmitted from his father. Marfan syndrome is an autosomal dominant systemic disease with a high degree of phenotypic variability. The FBN1 gene codes for fibrillin-1, a structural component of microfibrils, which are found in both elastic and non-elastic tissues. Mutations in the FBN1 gene can affect numerous organs including bones, eyes, skin, lungs, the central nervous system, and the cardiovascular system. The FBN1 gene is large and contains 65 exons. Over 800 disease-causing mutations have been found, with few representing recurrent mutations. Most mutations are unique to families, thus suggesting a high mutation rate. Mutations have been found in every exon and appear to be spread evenly throughout the gene. Among the mutations, two-thirds are missense mutations involving cysteine substitutions, as found in our patient. Mutations involving substitutions of cysteine correlated highly with the development of ectopia lentis. A severe or neonatal Marfan phenotype can be found with mutations in exons 24–27 and 31–32 and are thought to account for 20% of FBN1 mutations. This appears to be a “hot spot” as the gene length predicts only 14.5% of mutations. Mutations in this area are associated with more severe phenotypes, including earlier presentation, higher risk of scoliosis, ectopia lentis, ascending aorta dilatation, mitral valve abnormalities, and shorter survival.Reference Pyeritz 2

To the best of our knowledge, all the reported cases of neonatal Marfan syndrome have been sporadic, except one case reported by Tekin et al,Reference Tekin, Cengiz and Ayberkin 3 who described a familial occurrence of neonatal Marfan syndrome in three siblings of unaffected parents. Genetic testing of one of these patients showed a heterozygous c.3257G > A transition in exon 25 of FBN1. The three siblings died between the ages of 2 and 4 months because of cardiorespiratory failure secondary to neonatal Marfan syndrome.

Experimental studies in mice models of Marfan syndrome have demonstrated that excessive TGF-β signalling causes progressive aortic root dilatation. The treatment with the angiotensin II receptor blocker losartan, which is known to inhibit TGF-β signalling, prevented progressive enlargement of the aortic root.Reference Habashi, Judge and Holm 4 – Reference Gelb 6 Further, Brooke et alReference Brooke, Habashi, Judge, Patel, Loeys and Dietz 7 reported in their cohort study that initiation of angiotensin II receptor blocker therapy in 18 children with Marfan syndrome resulted in a significant reduction in the rate of change in the aortic root diameter as compared with β-blocker therapy alone. Our patient was treated with a combination therapy of losartan and propranolol at 3 months of age because of significant aortic root dilatation. During follow-up, serial echocardiogram studies showed a slow rate of progression of aortic root dilatation.

Conclusion

Neonatal Marfan syndrome is associated with a poor outcome; 50% of affected infants die during the first year of life because of cardiac complications. It is important to recognise neonatal Marfan syndrome in utero and shortly after birth to initiate the appropriate investigation and management. As the gene for Marfan syndrome was only identified in 1991 and clinical testing has been available for <10 years, many affected adults may not have undergone genetic testing and might be unaware of the severity of their mutation. We stress the importance of early recognition to anticipate and treat the cardiac abnormalities that are likely to arise, such as the ones that were detected soon after birth in the infant reported in this study. Losartan is a new therapy for stabilising aortic root dilatation in Marfan syndrome; it significantly slowed the rate of enlargement of the aorta in our patient.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the family for their positive support in reporting the medical data and clinical profile of their son.

Financial Support

This brief report received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have any conflict of interest about the manuscript.