Congenital long QT syndrome is a prototypic cardiac channelopathy with an estimated prevalence of about 1/2000 to 1/2500 persons.Reference Schwartz, Crotti and Insolia 1 This is characterised by abnormal cardiac repolarisation, resulting in QT interval prolongation that predisposes patients to life-threatening arrhythmias and sudden death. Left thoracic sympathectomy is an effective treatment for patients who are refractory to medical therapy or who need frequent defibrillator intervention. Although there is substantial literature about this therapy in adults, a few reports detail the outcomes in infants and children.Reference Steven, Jonathan and William 2

Case report

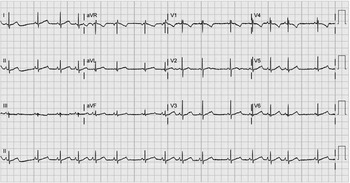

In 2014, a 10-week-old premature infant weighing 1.6 kg was referred to our institution for treatment of severe congestive cardiac failure related to a large muscular ventricular septal defect and patent ductus arteriosus. The patient was born at 26 weeks of gestation with birth weight of 830 g. During the initial evaluation, the electrocardiogram obtained showed a prolonged QTc of 550 ms with 2:1 atrioventricular conduction (Fig 1). There was no documented bradycardia during fetal life. The infant did not receive any QTc-prolonging medications. Holter recordings showed multiple short runs of ventricular tachycardia. Genetic evaluation showed that she was missing a part of one copy of chromosome 7 – 9.1 Mb deletion at 7q36.1-q36.3. This deleted region contains the gene for KCNH2, which is associated with prolonged QT interval. This was found to be a de novo deletion, and both parents were tested negative. Despite propranolol, the patient continued to have frequent ventricular tachycardia. There were no runs of Torsades de pointes and T wave alternans. The patient therefore underwent a median sternotomy and pulmonary artery banding with ligation of the patent ductus arteriosus. During the surgery, the left pleural space was opened, and a left thoracic sympathectomy at the level of thoracic vertebrae T2 and T3 was performed using electrocautery. The sympathetic chain was divided but not excised. The patient made an uncomplicated recovery with no signs of Horner’s syndrome. Postoperatively, her QTc normalised and it was around 435 ms. The patient stayed in the hospital for 35 days after the surgical procedure. During this time, she did not manifest any ventricular arrhythmias. Implantation of an implantable cardiac defibrillator or pacemaker was not considered in this patient as her QTc had normalised and she remained asymptomatic. She was discharged home on propranolol 2 mg/kg/day divided every 6 hours. On follow-up, she remained asymptomatic without any recurrent arrhythmias or syncope, although there was no Holter monitoring performed as an outpatient. By 10 months of age, the ventricular septal defect had closed spontaneously, and the pulmonary artery band was removed surgically. At this time, her electrocardiogram also showed an average QTc of 416 ms (Fig 2). We were able to gradually wean her off propranolol. She remained asymptomatic 1 year later. A recent follow-up electrocardiogram showed normal QTc intervals.

Figure 1 Sinus rhythm with prolonged QTc interval (550 ms) with 2:1 conduction. aVR=augmented vector right; aVL=augmented vector left; aVF=augmented vector foot

Figure 2 Sinus rhythm with an average QTc interval of 416 ms.

Discussion

Congenital long QT syndrome is a life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia syndrome, which is a leading cause of sudden death in the young. This is characterised by prolongation of the QT interval, resulting in arrhythmias associated with syncope and cardiac arrest.Reference Schwartz, Crotti and Insolia 1 The most common long QT syndrome genes are KCNQ1 (LQT1), KCNH2 (LQT2), and SCN5A (LQT3), accounting for around 90% of all genotype-positive cases.Reference Schwartz, Crotti and Insolia 1 , Reference Chang, Hsu and Hwang 3 The finding that the QT interval could be prolonged by right stellectomy and the successful treatment of a medically refractory young patient with long QT syndrome by left stellectomy led to the hypothesis that this disease was primarily a disorder of cardiac sympathetic innervation, although we now know that this is not the primary cause of this syndrome.

Although β-adrenergic blockade remains the therapy of choice for long QT syndrome, left thoracic sympathectomy may be useful for those with refractory arrhythmias or cardiac events not prevented by medication. In a recent report of 147 adult patients with the syndrome who underwent thoracic sympathectomy, the mean annual cardiac event per rate dropped by 91%.Reference Schwartz, Priori and Cerrone 4 Recent publications have focussed on the clinical applications of left cardiac sympathetic denervation for heart failure patients, especially those who are intolerant to β-adrenergic blockers.Reference Schwartz, Priori and Cerrone 4 , Reference De Ferrari and Schwartz 9 Generally, for long QT syndrome, the sympathetic chain is divided at the level of the stellate ganglion and the first six ribs;Reference Schwartz, Priori and Cerrone 4 – Reference Costello, Wilson and Louis 7 review of the literature showed a significant incidence of Horner’s syndrome with this approach.Reference Ouriel and Moss 8 Given the unique surgical challenges – small size and midline approach – we felt that the risk of Horner’s syndrome would be unacceptably high in this patient. Therefore, in our patient, we elected to only divide the sympathetic chain at the level of thoracic vertebrae T2 and T3. Our reasoning was that this may be equally effective and at the same time reduce the risk of Horner’s syndrome.

We could identify only isolated cases of this procedure being performed in infants or young children.Reference Kenyon, Flick, Moir, Ackerman and Pabelick 5 – Reference Costello, Wilson and Louis 7 In our patient, thoracic sympathectomy was associated with return to normal of the QT interval and complete resolution of all symptoms.

The results of this case study and literature review suggest that left thoracic sympathectomy is feasible and should be considered as an option for treating children with long QT syndrome, including neonates and young infants.

Acknowledgements

None.

Authors’ contribution: S.S. reviewed the literature, wrote the initial draft, carried out the final analysis of the draft, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. TK S.K. reviewed this manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. C.J.K.-C. reviewed and edited this manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.