The development of the atrial switch operation technique in the 1960s allowed patients with transposition of the great arteries to reach adulthood. The underlying principle of the atrial switch operation is the redirection of the blood flow on the atrial level leaving the right ventricle as systemic and the left ventricle as subpulmonary ventricle. Long-term survival rates after this procedure have been reported to be approximately 79% after 30 years. Reference Moons, Gewillig and Sluysmans1

However, the morphological, geometrical and contractile properties of the left and right ventricle are highly different. The right ventricle is only poorly suited to work as high-pressure chamber, predisposing the patients to early heart failure and secondary regurgitation of the systemic atrioventricular valve, that is, the morphologic tricuspid valve. Reference Piran, Veldtman, Siu, Webb and Liu2 Dysfunction of the systemic ventricle as well as late sequelae of the atrial septectomy and baffle creation lead to an increased burden of arrhythmias. The triad of systemic ventricular dysfunction, severe systemic atrioventricular valve (tricuspid valve) regurgitation, and atrial tachyarrhythmia has been associated with ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. Reference Schwerzmann, Salehian and Harris3,Reference Kammeraad, van Deurzen and Sreeram4

A similar phenomenon of early systolic heart failure development is noted in patients with combined atrioventricular and ventriculo-arterial discordance, that is, congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries, in which the morphological right ventricle has to operate as systemic ventricle as well. Reference Graham, Bernard and Mellen5 Two-thirds of the patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries initially present as adult with signs of systemic ventricular failure, 17% of those older than 60 years. Reference Beauchesne, Warnes, Connolly, Ammash, Tajik and Danielson6

Despite the differences in anatomy and clinical history, the patients with transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch and those with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries share a common final path predominantly shaped by the failing systemic right ventricle. However, in contrast to patients with left ventricular heart failure, there is no guideline-directed medical therapy with a proven effect on morbidity or mortality in systemic right ventricular dysfunction.

The aim of the current study was to provide a cross-sectional analysis documenting the clinical status regarding arrhythmia burden, cardiac function and presence of heart failure as well as the treatment reality of adult patients with systemic right ventricle in Germany.

Methods

Study design

All patients with transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation and patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries were identified in the German National Register for Congenital Heart Defects (NRCHD) database.

The NRCHD is the national repository for medical data on patients with CHDs in Germany. With 52,582 members (as of May 2017), the NRCHD is Europe’s largest registry for patients with CHD and can be viewed as a basis for representative studies. Reference Helm, Koerten, Abdul-Khaliq, Baumgartner, Kececioglu and Bauer7 Registration is voluntary through self-enrollment of patients affected by CHD or their parents, which is facilitated through collaboration between all treating institutions and self-help groups. The NRCHD has extensive experience in data collection via online surveys. The established data infrastructure of the NRCHD allows data to be stored within the framework of a specific data protection concept, which is registered with the Berlin Official for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (no. 531.390). General approval by the ethics review board of the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany, is available for all research conducted within the scope of the registry.

The database already contained baseline characteristics of the patients. The main cardiac diagnosis, all concurrent cardiac anomalies as well as all performed cardiac interventions and operations are recorded in a database using the International Pediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code (IPCCC) published by the International Society for Nomenclature of Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease (ISNPCHD; http://www.ipccc.net). The database was amended with data from the most current medical reports (ranging from 2008 to 2018, median of the used discharge letters = 2016; 74.9% of the letters were dated between 2016 and 2018.) of the identified patients regarding functional parameters as well as current medication. Data on the functional NYHA class at the latest clinical presentation were extracted from the medical notes.

If classification was noted in the letter, it was directly transferred. If the NYHA class was not specified, but exercise capacity reported, patients were classified in the respective NYHA class accordingly. A single person was responsible for the data analysis ensuring a homogeneous analysis. If there was incomplete information, we were unfortunately not able to assign a NYHA class and missing data have been filed. Echocardiographic parameters were also manually collected from the medical reports. Due to the nature of the study in the majority of cases, systolic ventricular function or valvular function was only available semi-quantitatively, meaning that no exact numbers depicting the ejection fraction were obtained but rather a grading in normal versus light, moderate, or severe reduction of systolic function has been used.

In addition, the presence or absence of a left ventricular outflow tract obstruction was predominantly available as dichotomous variable.

Polypharmacy was defined as using five or more different cardiovascular drugs as specified in the discharge letter according to Mulder et al. Reference Woudstra, Kuijpers and Meijboom8 The following drug classes were counted: beta-blocker, ACE-inhibitor/ARB/ARNI, MRA, diuretics, ivabradine, digitalis, anticoagulation, platelet inhibitors, and statin.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistics version 27.

Statistical differences between dTGA and ccTGA group for metric variables like age or body weight have been analysed using independent t-test. Statistical differences for nominal and binary variables like previous surgery, history of arrhythmia, or presence of ventricular dysfunction have been analysed using Pearson’s chi-square test. Multivariable ordinal logistic regression analyses were performed with systemic right ventricle dysfunction as dependent variable separately for the dTGA and ccTGA group. Variables systemic right ventricle function, left ventricular function, systemic atrioventricular valve regurgitation are ordinal parameters. Presence of internal cardioverter defibrillator, pacemaker, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, or history of arrhythmia are binary parameters. The variable age was the only metric parameter. Analyses evaluating frequency of drug use were performed with Poisson’s log-linear analysis. Due to the exploratory nature of this observational study, no p-value adjustments were conducted. A p-value of less than 5% was considered as statistically significant.

Statistical analysis has been approved by the statistics department of the RWTH in individual coaching sessions.

Results

Study population

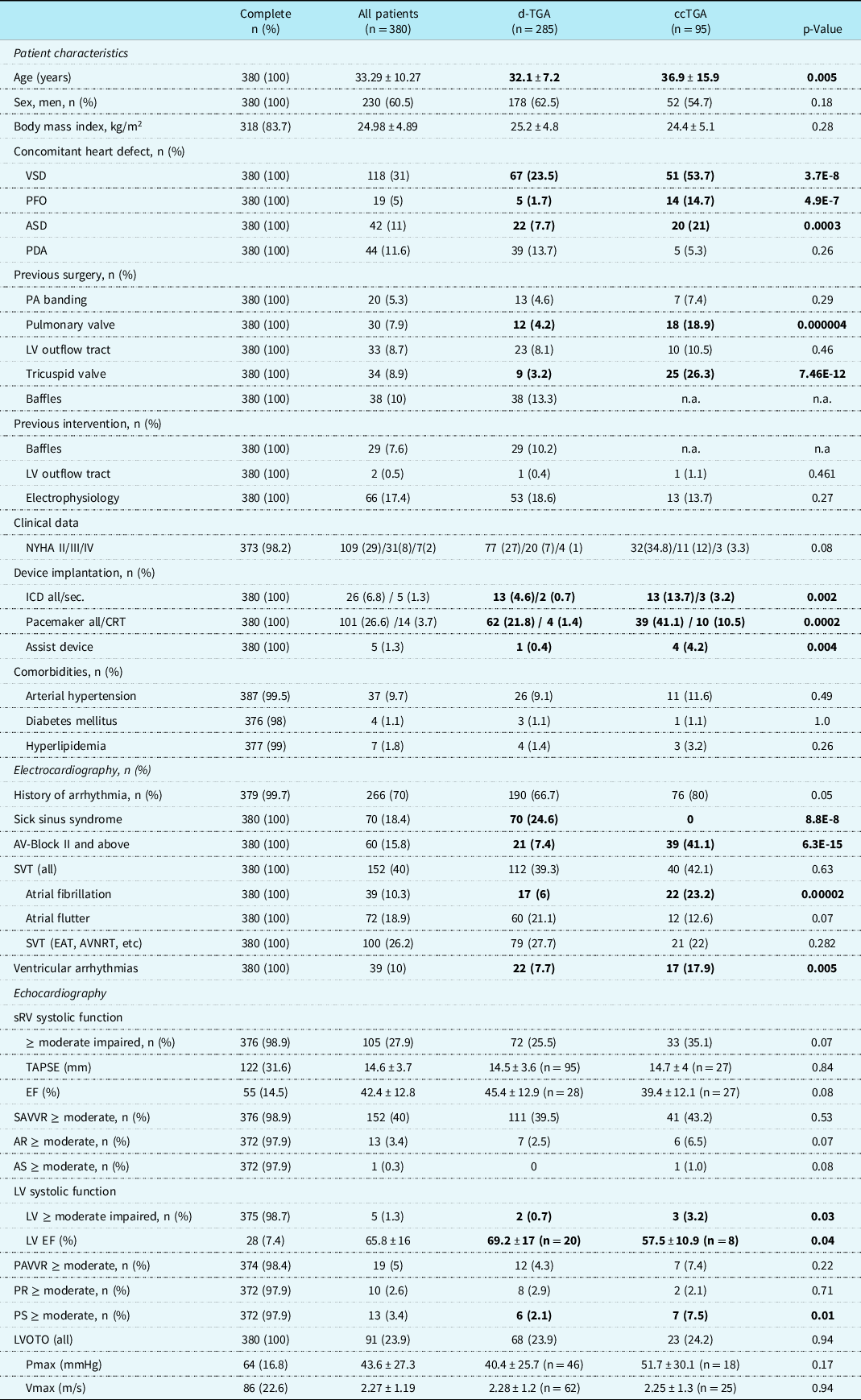

Overall, 285 patients with transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation and 95 patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries were included. The baseline characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. Patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries were significantly older and had more often prior surgery of the pulmonary or tricuspid valve (transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch vs. congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries: age: 32.1 ± 7.2 vs. 36.9 ± 15.9 years, p < 0.01; pulmonary valve surgery 4.2% vs. 19%, p < 0.01; tricuspid valve surgery 3.2% versus 26%, p = 0.005). In addition, patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries were more likely to have been provided with a pacemaker or an internal cardioverter defibrillator (pacemaker 21.8% versus 41.1%, p = 0.0002; internal cardioverter defibrillator 4.6% versus 13.7%, p = 0.002) compared to patients after atrial switch. The majority of patients were in NYHA functional class I or II (transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch: NYHA I/II 63/27%; congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries: 48/34%, respectively). NYHA III and IV symptoms were described in only 7% and 1% of the patients with transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch versus 12% and 3% in congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries, respectively. These differences were not statistically different. Baseline data for the atrial switch subgroups according to Mustard or Senning procedure did not significantly differ and are therefore not shown.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of all patients and the subcohort of patients with transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation (dTGA) or patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (ccTGa)

Bold value represents p- value < 0.5.

Heart failure and tricuspid regurgitation

Basic echocardiographic findings, as reported in the analysed discharge letters, were compared. There was no significant difference in systolic right ventricular function or systemic atrioventricular valve regurgitation between patients after atrial switch operation or congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries, if semiquantitative values were analysed. Systolic function of the right ventricle was moderately or severely reduced in 25.5% of the atrial switch patients and 35.1 % of the congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries patients, being accompanied by a relevant regurgitation of the systemic atrioventricular valve in 39.5% and 43.2% of the cases, respectively (Table 1). Objective parameters regarding systemic right ventricular systolic function were not uniformly mentioned in the reports, hindering a more detailed analysis. In patients with transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation, tricuspid anular plane systolic excursion was noted in 33% and right ventricular ejection fraction in 10%, in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries in 28% and 28%, respectively. Only a very few patients did also show a reduction in left ventricular systolic function (n = 2/0.7% atrial switch group, n = 3/3.2% congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries, p = 0.03) (Table 1). There was no difference in pulmonary atrioventricular valve regurgitation. There was also no difference in function of the aortic or pulmonary valve. An obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract was present in 23.9% of the patients after atrial switch and 24.2% of the patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries.

Ordinal logistic regression analyses have been performed to evaluate the association of several clinical and echocardiographic characteristics with systemic right ventricular dysfunction in both groups (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Ordinal logistic regression analysis evaluating factors associated with systemic right ventricle dysfunction in transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation (A-dTGA) or congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (B-ccTGA) patients. Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval; ICD = internal cardioverter defibrillator; LV fnct = left ventricular function; LVOTO = left ventricular outflow tract obstruction; OR = odds ratio; sRV = systemic right ventricle; SAVVR = systemic atrioventricular valve regurgitation.

Regurgitation of the systemic atrioventricular valve was associated with systemic right ventricular dysfunction in the atrial switch group but not in the group with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (atrial switch group OR 1.6 (1.1–2.3), p = 0.008; congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries OR 1.3 (0.7–2.5) p = 0.377). The calculated odds ratio of 1.6 in the atrial switch groups reflects a 60% increase in probability of the presence of a systemic right ventricular dysfunction with each increase in atrioventricular valve regurgitation severity.

In contrast, there was a positive association of history of tricuspid valve repair with systemic right ventricular function in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries but not in patients after atrial switch operation (congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries OR 14.9 (95% CI 4.2–60.2), p = 0.00006 versus atrial switch subgroup OR 1.2 (95% CI 0.24–5.6) p = 0.84) (Fig 1).

There was also a significant positive correlation of right ventricular with left ventricular dysfunction in the TGA and ccTGA group, implicating that there is a significant increase in the likelihood for the presence of right ventricular dysfunction with each grade in decline of left ventricular dysfunction. However, since left ventricular dysfunction in this cohort in general was rare, the impact of this finding has still to be evaluated (congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries OR 17.2 (95% CI 4.8–80.3), p = 0.00007 versus atrial switch subgroup OR 12.9 (95% CI 3.3–68.9) p = 0.0005) (Fig 1).

The presence of an Internal Cardioverter Defibrillator was significantly associated with systemic right ventricular function in the atrial switch group but showed only a trend in those patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (atrial switch OR 7.2 (95% CI 2.15–25.6) p = 0.002; congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries OR 4.2 (95% CI 0.99–19.5), p = 0.055). History of arrhythmia was significantly correlated in the atrial switch but not in the group of patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (arrhythmia: atrial switch group OR 2.1 (95% CI 1.2–3.7) p = 0.007; congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries OR 0.62 (0.18–2.16) p = 0.440) (Fig 1).

The history of a left ventricular outflow tract stenosis was inversely associated with a dysfunction of the systemic ventricle in both groups (transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation OR 0.49 (95% CI 0.26–0.87) p = 0.018; congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries OR 0.16 (95% CI 0.03–0.69) p = 0.025) (Fig 1). The calculated odds ratio of 0.49 in the atrial switch groups reflects a 51% decrease in probability of a systemic right ventricular dysfunction if a left ventricular outflow tract obstruction is present, the odds ratio of 0.16 in those patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries a 84% reduction in probability, respectively.

In 62 patients after atrial switch operation and 25 patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries, the left ventricular outflow tract velocity was stated as objective measure for severity of the left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation 2.28 m/s ± 1.15 m/s; congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries 2.25 ± 1.3 m/s) (Table 1). Non-parametric Spearman regression analysis showed an inverse correlation of left ventricular outflow tract velocity and systemic ventricle systolic function in patients after atrial switch operation (rs −0.39, p = 0.002) and a similar trend in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (rs −0.39, p = 0.064).

History of arrhythmia

A significant percentage of patients had a history for arrhythmia. Most common were supraventricular tachycardia including atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Atrial fibrillation was more common in congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries patients (atrial fibrillation: congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries n = 22 (23%) versus transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation n = 17 (6%), p = 0.00002), whereas there was no significant difference in the occurrence of other supraventricular tachycardia (Table 1).

Analyzing the subgroups of the transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation group after Mustard or Senning procedure, a significant increase in prevalence of arrhythmia was detected in the Mustard group regarding atrial flutter, supraventricular tachycardias other than atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter as well as ventricular tachycardia (Mustard versus Senning: atrial flutter n = 37 (30.1%) versus n = 23 (14.2%), p = 0.001; supraventricular tachycardias (other) n = 44 (35.8%) versus n = 35 (21.6%), p = 0.008; ventricular tachycardias n = 15 (12.2%) versus n = 7 (4.3%), p = 0.014) (Table 1 supplement).

Ventricular arrhythmias were rare in the whole group (congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries and transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation) compared to supraventricular arrhythmias. If so, ventricular arrhythmias were more often described in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries than patients after atrial switch (patients after atrial switch operation n = 22 (7.7%) versus congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries n = 17 (17.9%), p = 0.005; Table 1). In the subgroup of patients after atrial switch operation, a higher prevalence of ventricular tachycardia was noted in the Mustard compared to the Senning type operation (Mustard n = 15 (12.2%) versus Senning n = 7 (4.3%), p = 0.014) (Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence of arrhythmia burden after Senning or Mustard operation for transposition of the great arteries

Bold value represents p- value < 0.5.

Conduction disorders in terms of higher-grade atrioventricular blocks were significantly more common in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries than patients after atrial switch operation (congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries 41.1%, transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation 7.4%, p < 0.0001), whereas sick sinus syndrome was more common in patients after atrial switch operation (congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries 0%, transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation 24.6%, p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Pharmacological therapy

The use of cardiovascular medication was common in patients with systemic right ventricle. Fifty-six per cent of the patients of the whole cohort had at least one cardiovascular drug. Beta-blockers (67.6%), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (46.7%), and diuretics (46.7%) were mainly prescribed followed by mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (37.1%) or anticoagulation (40%). None of the patients received a SGLT2 inhibitor like dapagliflozin. Polypharmacy, that is, prescription of five or more drugs, was rare and only documented in 4.5% of the whole systemic right ventricle cohort. In patients with relevant (moderate or severe) right ventricular dysfunction, polypharmacy was detected in 30% of the patients. However, 14% of all patients did not take any cardiovascular medication at all despite right ventricular dysfunction. Further analysis showed that pharmacologic therapy with beta-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, diuretics, anticoagulation, and statins was significantly less often prescribed in patients after atrial switch compared to patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries despite a similar prevalence of right ventricular dysfunction (Table 3). Combination therapy consisting of beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blocker was prescribed only in 15.3% of the patients after atrial switch operation compared to 33.3% in the group with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. A triple therapy adding a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists was used in 19.4% of the patients after atrial switch versus 42.4% of the congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries patients, although implicating a clinically importance these differences however did not reach a statistical significance.

Table 3. Use of cardiovascular medication in patients with transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation (dTGA) or congenitally corrected TGA (ccTGA) with and without systolic dysfunction of the systemic ventricle

Bold value represents p- value < 0.5.

Factors associated with polypharmacy

We further aimed in analysing factors associated with pharmacological cardiovascular therapy in all patients with systemic right ventricle. Polypharmacy, defined as taking more than five cardiovascular drugs, was noted in 39 patients with an age of 42 ± 14 years. Those who received a greater amount of cardiovascular drugs were predominantly male (72%). Systemic right ventricular function was reduced in 80% and 92% had a history of arrhythmia. A pacemaker was present in 64% and an internal cardioverter defibrillator in 31%. Tricuspid valve repair had been performed in 39% and 10% had an arterial hypertension. Poisson loglinear regression analysis revealed several clinical factors associated with the amount of cardiovascular drugs used. Strongest associations were detected with a history of arrhythmia, functional NYHA class as well as systemic right ventricular function (arrhythmia incidence rate ratio (IRR) 1.77, 95%CI 1.36–2.34, p < 0.0001; NYHA class IRR 1.35, 95%CI 1.21–1.50, p < 0.0001, systemic right ventricle function IRR 1.25, 95%CI 1.14–1.36, p < 0.0001). The incidence rate ratio showed that patients in NYHA class III take 1.35 times more cardiovascular drugs than patients in NYHA class II and patients with moderate reduction in right ventricular function are prescribed 1.25 times more cardiovascular drugs than patients with mild right ventricular dysfunction. Patients with previous tricuspid valve repair or pacemaker implantation also had a higher likelihood for a larger quantity of drugs used (tricuspid valve repair IRR 1.61, 95%CI 1.26–2.05, p < 0.0001; pacemaker IRR 1.52 95%CI 1.28–1.82, p < 0.0001). Co-morbidities like arterial hypertension and the respective age showed a positive association with the amount of drugs used (arterial hypertension IRR 1.44, 95%CI 1.12–1.83, p = 0.004; age IRR 1.01 95%CI 1.01–1.02, p = 0.001) (Fig 2).

Figure 2. Poisson loglinear analysis evaluating factors associated with polypharmacy in all patients. Abbreviation: aHT = arterial hypertension; CI = confidence interval; IRR = incidence rate ratio; SAVVR = systemic atrioventricular valve regurgitation; sRV fnct = systemic right ventricular function.

Discussion

Based on the database of the National Register for Congenital Heart Disease, we were able to report on a cohort of 380 adult patients with a systemic right ventricle with regards to their long-term outcome.

Long-term outcome

In the literature, the percentage of patients with systemic right ventricular dysfunction ranges from 60% in patients after Mustard operation (n = 91, mean age 35.8 years Reference Cuypers, Eindhoven and Slager9 ) to 46% in a Dutch cohort (n = 76, 30 years post-operative Reference Couperus, Vliegen and Zandstra10 ) and 26% in an Australian group (n = 83, mean age 35 ± 5 years Reference Dennis, Kotchetkova, Cordina and Celermajer11 ). Deterioration of systolic right ventricular function correlating with age has also been shown in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. By the age of 45 years, two-third of the patients with complex congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries and 25% of the patients with simple congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries experience a relevant dysfunction of the systemic ventricle. Reference Graham, Bernard and Mellen5

In our cohort of 285 patients with atrial switch operation and 95 patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries, systolic function of the systemic right ventricle was at least moderately reduced in approximately one-third of the patients in their third life decade. Of the whole cohort, 40% presented with moderate or severe regurgitation of the systemic atrioventricular valve. There was no significant difference in systemic right ventricle dysfunction or systemic atrioventricular valve regurgitation between patients after atrial switch operation and patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries despite the older age of the congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries patients and the supposedly more complex disease in this subgroup reflected by a higher percentage of associated defects and history of previous surgery.

Logistic regression analysis revealed a significant positive association of systemic atrioventricular valve regurgitation and history of arrhythmia with systemic right ventricle dysfunction in patients with transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation. This supports the previously postulated vicious cycle of failing right ventricular function, secondary systemic atrioventricular valve regurgitation, increased atrial pressure predisposing for supraventricular tachycardia. The myocardial oxygen supply/demand mismatch in the setting of supraventricular tachycardia might trigger ventricular arrhythmia and expose the patient at risk for sudden cardiac death. Reference Khairy12 The positive association of the presence of an internal cardioverter defibrillator with right ventricular dysfunction – as seen in our cohort in patients with transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation – does point into the direction of a high awareness for the existent sudden cardiac death risk.

In patients with congenitally corrected transposition, there was a positive association of systemic right ventricular dysfunction with older age and a history of tricuspid, that is, systemic atrioventricular valve repair but not with systemic atrioventricular valve regurgitation itself, reflecting a more advanced stage, that already necessitated a valve intervention in the past.

Furthermore, our analysis revealed an inverse correlation of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction with systemic right ventricular function in patients with atrial switch operation as well as in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries, suggesting a positive effect of the left ventricular outflow tract obstruction on cardiac haemodynamics and thereby a protective effect on right ventricular systolic function on the long term.

A small study in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries did report a reduction in tricuspid regurgitation after pulmonary artery banding due to an increase in left ventricular pressure and a concomitant septal shift that ameliorates right ventricular geometry. Reference Kral Kollars, Gelehrter, Bove and Ensing13 Budts and colleagues were able to show that the presence of a left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (n = 24 with versus n = 38 without left ventricular outflow tract obstruction) was associated with an improved outcome in terms of progression-free survival for congestive heart failure, cardiovascular mortality, or heart transplantation. Reference Helsen, De Meester and Van Keer14 A recent report translated this to patients with transposition of the great arteries and systemic right ventricle. The study evaluated systolic function with cardiac MRI in 12 patients after atrial switch and 1 patient with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries and left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in comparison to patients with the same underlying anatomy without left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Patients with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction had a significantly higher left and right ventricular ejection fraction than those without. However, this did not correlate to a higher exercise capacity. Reference Stauber, Wey and Greutmann15

Our cohort included 68 patients in the atrial switch group and 23 patients in the subgroup with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries and presence of a left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Patients with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction had a 51% and 84% less likelihood for a dysfunction of the systemic right ventricle in patients after atrial switch operation and patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries, respectively. These findings might strengthen the hypothesis that an increase in left ventricular pressure ameliorates right ventricular function over the long term. Further studies are needed to clarify a causal relationship between left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and right ventricular dysfunction.

As identified previously. a significant number of patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries and transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation had a history of arrhythmia. Supraventricular tachycardia were more prevalent than ventricular tachycardia in both groups. Atrial re-entry tachycardia like atrial flutter were more common in the subgroup of patients after Mustard than after Senning operation, as described in previous studies. Reference Deal16 Ventricular tachycardia occurred in 18% of the patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries hence significantly more often than in patients with transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation. Kapa and colleagues did report the occurrence of sustained ventricular tachycardia requiring defibrillation or cardiac arrest in 23% of patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries and right ventricular ejection fraction <35% during a follow-up of 7.2 ± 3.4 years. Reference Kapa, Vaidya and Hodge17 Due to the cross-sectional design of our study, we are not able to evaluate the impact of the arrhythmia burden on cardiovascular outcome. However, it is important to note that in our cohort – in contrast to patient after atrial switch operation – there was no association of right ventricular dysfunction with arrhythmia in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries implicating a different pathophysiological background.

Treatment reality

Up to the current date, the effects of specific pharmacological heart failure therapy in the failing systemic right ventricle is still unclear.

The angiotensin receptor blocker Valsartan reduced cardiovascular event rate in a randomised multi-center trial in 88 patients with systemic right ventricle (arrhythmias, worsening of heart failure or tricuspid valve surgery). Reference van Dissel, Winter and van der Bom18 Guideline-directed medical heart failure therapy stabilised heart failure symptoms over the follow-up of 10.3 years in patients with systemic right ventricle according to an analysis of the Swedish National Registry on Congenital Heart Disease, without a change in mortality. Reference Skoglund, Heimdahl and Mandalenakis19

A recent meta-analysis concluded that due to the small sample size of the available studies and the lack of a randomised design at present, there is no conclusive evidence for the effectiveness of a medical therapy with beta-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blocker or aldosterone antagonists in systemic right ventricular dysfunction in adults. Reference Zaragoza-Macias, Zaidi, Dendukuri and Marelli20 There is also no formal recommendation for use of heart failure medication in the current guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology. Reference Baumgartner, De Backer and Babu-Narayan21 In symptomatic patients, however validated strategies from patients with left ventricular heart failure are still transferred.

We are able to show that despite the presence of a relevant right ventricular dysfunction, only 34% of the patients after atrial switch operation received combination heart failure therapy and 19% no drug therapy at all. In contrast, about twice as many patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries had a combination heart failure drug therapy prescribed. Prevalence of right ventricular failure and systemic atrioventricular valve regurgitation was similar in patients with transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation and patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries, despite an older age and more complex disease in the group with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries, indirectly suggesting a protective effect of the pharmacological heart failure therapy.

Polypharmacy, that is, prescription of more than five drugs has been correlated with increased mortality in adult CHD survivors in general. Reference Woudstra, Kuijpers and Meijboom8 Polypharmacy though was rare in our study cohort, applying to only 4.5% of the overall group and 14.4% of those with systemic right ventricle dysfunction underlining the fact that caretakers are very restrictive regarding the prescription of cardiovascular drugs in patients with congenital systemic right ventricle.

Limitations

The data are retrospectively collected from a large database. Clinical and functional parameters had to be extracted from written medical reports, and no original data like echocardiographies were available. Therefore, for the echocardiographic classification of the systolic function and the severity of valve disease, we had to rely on semiquantitative grading and interpretation as specified in the respective report. We were also not able to grade the severity of the left ventricular outflow tract obstruction ourselves which was therefore included as dichotomous trait.

Participation in medical registers is voluntary in Germany. Therefore, we are not able to rule out a selection bias and were only able to evaluate the outcome in a subset of adults with systemic right ventricle. Even though the stately number of participants in our study can be considered representative, results should be classified as hypothesis generating.

Conclusions

The cross-sectional analysis of 380 adult patients with systemic right ventricle confirms the high prevalence of systemic right ventricular failure, systemic atrioventricular valve regurgitation as well as arrhythmias. The presence of a left ventricular outflow tract obstruction emerged as a potentially protective factor in regard to systemic right ventricular function. Pharmacological heart failure therapy is not universally used in failing systemic right ventricle and polypharmacy is rare. Cardiovascular drugs were more often prescribed in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries than transposition of the great arteries after atrial switch operation. In contrast, systemic right ventricular dysfunction was similar in both groups, despite a more complex disease in congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries patients, indirectly supporting a positive impact of pharmacological heart failure treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following colleagues for recruiting patients and for providing medical reports for analysis:

Gunter Kerst, Klinik für Kinderkardiologie; Jaime F. Vazquez-Jimenez, Herzchirurgie für Kinder und Erwachsene mit angeborenen Herzfehlern, Universitätsklinikum Aachen; Aachen. Dimitrios Gkalpakiotis, Praxis für Kinderkardiologie; Aachen. Andrea Schedifka, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Ahrensfelde. Gernot Buheitel, Joachim Streble, II. Klinik für Kinder und Jugendliche, Universitätsklinikum Augsburg; Augsburg. Kai Thorsten Laser, Kinderherzzentrum/Zentrum für angeborene Herzfehler, Klinik für Kinderkardiologie und angeborene Herzfehler; Eugen Sandica, Kinderherzzentrum/Zentrum für angeborene Herzfehler, Klinik für Kinderherzchirurgie und angeborene Herzfehler, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW; Bad Oeynhausen. Burkhard Trusen, Praxis Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologe; Bamberg. Felix Berger, Oliver Miera, Stanislav Ovroutski, Björn Peters, Katharina Schmitt, Stephan Schubert, Klinik für angeborene Herzfehler und Kinderkardiologie; Joachim Photiadis, Klinik für die Chirurgie Angeborener Herzfehler/Kinderherzchirurgie, Deutsches Herzzentrum Berlin; Berlin. Felix Berger, Bernd Opgen-Rhein, Katja Weiss, Klinik für Pädiatrie mit Schwerpunkt Kardiologie, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Campus Virchow-Klinikum; Berlin. Christoph Berns, Praxis für Kinderheilkunde, Jugendmedizin und Kinderkardiologie; Berlin. Carl-Christian Blumenthal-Barby, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Berlin. Thomas Boeckel, Guido Haverkämper, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Berlin. Andreas Kästner, Heike Koch, Christian Köpcke, Gemeinschaftspraxis für Pädiatrische Kardiologie;Berlin. Frank Streichan, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Berlin. Jens Timme, Birgit Franzbach, Gabriela Senft, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie und Erwachsene mit angeborenem Herzfehler; Berlin. Frank Beyer, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Bielefeld. Klaus Winter, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, St.-Agnes-Hospital; Bocholt. Johannes Breuer, Zentrum für Kinderheilkunde, Abteilung für Kinderkardiologie; Bahman Esmailzadeh, Klinik und Poliklinik für Herzchirurgie, Universitätsklinikum Bonn; Bonn. Martin Schneider, Abteilung Kinderkardiologie; Boulos Asfour, Abteilung für Kinderherzherzchirurgie, Deutsches Kinderherzzentrum Universitätsklinikum Bonn, Bonn. Jens Bahlmann, Eberhard Griese, Kinderkardiologische Gemeinschaftspraxis; Braunschweig. Trong Phi Lê, Klinik für strukturelle und angeborene Herzfehler/Kinderkardiologie, Klinikum Links der Weser; Bremen.Joachim Hebe, Jan-Hendrik Nürnberg, Elektrophysiologie Bremen, Zentrum Bremen am KlinikumLinks der Weser; Bremen. Annette Magsaam, Praxis für Kinderkardiologie und Angeborene Herzfehler; Bremen. Ronald Müller, Praxis für Angeborene Herzfehler/Kinderkardiologie; Bremen. Ludger Potthoff, Praxis Celler Centrum für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Celle. Renate Voigt, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Chemnitz. Tim Krüger, Kinderarzt-Praxis Ilmenau/Coburg, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Coburg. Hubert Gerleve, Ulrich Kleideiter, Kinder- und Jugendklinik, Christophorus-Kliniken Coesfeld; Coesfeld. Dirk Schneider-Kulla, Klinik für Pädiatrie/Kinder- und Jugendheilkunde, Kinderkardiologie; Jürgen Krülls-Münch, I. Medizinische Klinik, Klinik für Kardiologie, Angiologie und internistische Intensivtherapie, Carl-Thiem-Klinikum Cottbus; Cottbus. Elmo Feil, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Darmstadt. Thomas Menke, Kinderkardiologie, Vestische Kinder- und Jugendklinik Datteln; Datteln. Martin Lehn, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendkardiologie und für Erwachsene mit angeborenen Herzfehlbildungen; Dortmund. Antje Heilmann, Helge Tomczak, Praxis für Kinderkardiologie, Kinderzentrum Dresden- Friedrichstadt; Dresden. Otto N. Krogmann, Gleb Tarusinov, Klinik für Kinderkardiologie - angeborene Herzfehler; Michael Scheid, Klinik für Herz- und Gefäßchirurgie; Duisburg. Ertan Mayatepek, Frank Pillekamp, Klinik für Allgemeine Pädiatrie, Neonatologie und Kinderkardiologie; Artur Lichtenberg, Klinik für Kardiovaskuläre Chirurgie, Universitätsklinikum Düsseldorf; Düsseldorf. Christiane Terpeluk, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Ehingen. Veronika von Jan, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinder- und Jugendkardiologie und EMAH; Erfurt. Sven Dittrich, Kinderkardiologische Abteilung; Ulrike Gundlach, Medizinische Klinik 2 - Kardiologie und Angiologie; Robert Cesnjevar, Kinderherzchirurgische Abteilung, Universitätsklinikum Erlangen, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg; Erlangen. Ulrich Neudorf, Klinik für Kinderheilkunde III, Abteilung für Pädiatrische Kardiologie Universitätsklinikum Essen; Essen. Geert Morf, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin und EMAH, Kinderkardiologie; Flensburg. Anoosh Esmaeili, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie, Universitätsklinikum Frankfurt; Frankfurt. Stephan Backhoff, Praxis für Kinderkardiologie/angeborene Herzerkrankungen; Frankfurt. Brigitte Stiller, Zentrum für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Klinik für Angeborene Herzfehler/Pädiatrische Kardiologie; Friedhelm Beyersdorf, Klinik für Herz- und Gefäßchirurgie; Johannes Kroll, Klinik für Herz- und Gefäßchirurgie, Sektion Kinderherzchirurgie, Universitäts-Herzzentrum Freiburg Bad Krozingen; Freiburg. Nicole Häffner, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Freiburg. Jannos Siaplaouras, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie, Erwachsene mit angeborenem Herzfehler, Bluttransfusionswesen am Herz-Jesu-Krankenhaus; Fulda. Antje Masri-Zada, Praxis für Kardiologie; Gera. Christian Jux, Klinik für Kinderkardiologie und angeborene Herzfehler; Andreas Böning, Hakan Akintürk, Klinik für Herz-, Kinderherz- und Gefäßchirurgie, Universitätsklinikum Gießen und Marburg; Gießen. Thomas Paul, Matthias Sigler, Klinik für Pädiatrische Kardiologie und Intensivmedizin mit Neonatologie und Pädiatrischer Pneumologie; Theodor Tirilomis, Klinik für Thorax-, Herz- und Gefäßchirurgie – Schwerpunkt Kinderherzchirurgie, Universitätsklinikum Göttingen; Göttingen. Gabriele Schürer, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Greiz. Johannes Hartmann, Schwerpunktpraxis für Kinder- und Jugendkardiologie; Hagen. Ralph Grabitz, Uta Liebaug, Universitätsklinik und Poliklinik für Pädiatrische Kardiologie, Universitätsklinikum Halle (Saale); Halle. Claudius Rotzsch, Kinderkardiologische Praxis; Halle. Rainer Kozlik-Feldmann, Klinik und Poliklinik für Kinderkardiologie; Jörg Sachweh, Arlindo Riso, Herzchirurgie für angeborene Herzfehler, Universitäres Herz- und Gefäßzentrum UKE Hamburg; Hamburg. Stefan Renz, Andreas Schemm, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie und EMAH; Hamburg. Bernd Friedrich, Otmar Schlobohm, Kinder- und Jugendarztpraxis, Kinderkardiologie; Hamburg. Philipp Beerbaum, Dietmar Böthig, Klinik für Pädiatrische Kardiologie und Intensivmedizin; Alexander Horke, Chirurgie angeborener Herzfehler; Johann Bauersachs, Mechthild Westhoff-Bleck, Klinik für Kardiologie und Angiologie, Medizinische Hochschule Hannover; Hannover. Matthias Gorenflo, Zentrum für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin Pädiatrische Kardiologie/Angeborene Herzfehler, Matthias Karck, Tsvetomir Loukanov, Klinik für Herzchirurgie, Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg; Heidelberg. Hermann Schrüfer, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Hettstadt. Martin Wilken, Kinderarzt-Praxis Hof/Nail; Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Hof. Hashim Abdul-Khaliq, Tanja Rädle-Hurst, Axel Rentzsch, Klinik für Pädiatrische Kardiologie; Hans-Joachim Schäfers, Klinik für Thorax- und Herz-Gefäß-Chirurgie, Universitätsklinikum des Saarlandes;Homburg. Hagen Reichert, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Reisemedizin, Gelbfieberimpfstelle; Homburg. Thomas Kriebel, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie, Westpfalz-Klinikum; Kaiserslautern. Arnulf Boysen, Schwerpunktpraxis für angeborene Herzfehler; Karlsruhe. Anselm Uebing, Klinik für angeborene Herzfehler und Kinderkardiologie; Joachim Thomas Cremer, Jens Scheewe, Klinik für Herz- und Gefäßchirurgie, Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein; Kiel. Regina Buchholz-Berdau, Peter Möller, Gemeinschaftspraxis der Kinder- und Jugendärzte und Kinderkardiologen; Kiel. Wolfgang Ram, Praxis für angeborene Herzfehler; Kiel. Konrad Brockmeier, Klinik und Poliklinik für Kinderkardiologie, Gerardus B. W. E. Bennink, Klinik und Poliklinik für Herz- und Thoraxchirurgie, Schwerpunkt Kinderherzchirurgie, Uniklinik Köln; Köln. Alex Gillor, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendkardiologie; Köln.Tim Niehues, Peter Terhoeven, Zentrum für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie, HELIOS Klinikum Krefeld; Krefeld. Steffen Leidig, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Lauf. Ingo Dähnert, Peter Kinzel, Klinik für Kinderkardiologie; Martin Kostelka, Klinik für Herzchirurgie, Kinderherzchirurgie, Herzzentrum Leipzig; Leipzig. Liane Kändler, Medizinisches Versorgungszentrum Jessen, Außenstelle Wittenberg und Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Paul Gerhardt Diakonie und Pflege GmbH; Lutherstadt Wittenberg. Martin Bethge, Stefan Köster, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie und EMAH; Lübeck. Christoph Schröder, Praxis für Kinderkardiologie, Kinderpneumologie, Erwachsene mit angeborenen Herzfehlern; Lüneburg. Jens Karstedt, Kardiologische Schwerpunkpraxis für Kinder und Jugendliche am Klinikum Magdeburg; Magdeburg. Uwe Seitz, Praxis für Kinder- Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Maintal. Christoph Kampmann, Zentrum für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Abteilung für Kinderkardiologie, Christian-Friedrich Vahl, Klinik und Poliklinik für Herz-, Thorax- und Gefäßchirurgie, Universitätsmedizin der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz; Mainz. Frank Stahl, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendkardiologie, arterielle Hypertonie bei Kindern und Jugendlichen, Erwachsene mit angeborenen Herzfehlern; Mannheim. Mojtaba Abedini, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendkardiologie am Universitätsklinikum Gießen und Marburg; Marburg. Joachim Müller-Scholden, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Marktheidenfeld. Peter Ewert, Alfred Hager, Harald Kaemmerer, Nicole Nagdyman, Jörg Schoetzau, Oktay Tutarel, Klinik für Kinderkardiologie und Angeborene Herzfehler; Rüdiger Lange, Klinik für Herz- und Gefäßchirurgie; Jürgen Hörer, Klinik für Chirurgie angeborener Herzfehler und Kinderherzchirurgie Deutsches Herzzentrum München; München. Nikolaus A. Haas, Abteilung Kinderkardiologie und Pädiatrische Intensivmedizin; Lale Rosenthal, Herzchirurgische Klinik und Poliklinik, Sektion Kinderherzchirurgie; Klinikum der Ludwig- Maximilians-Universität; München. Michael Hauser, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendkardiologie und Erwachsene mit angeborenen Herzfehlern; München. Alexander Roithmaier, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Schwerpunktpraxis für Kinder- und Jugendkardiologie; München. Hans-Gerd Kehl, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin - Pädiatrische Kardiologie, Edward Malec, Department für Herz- und Thoraxchirurgie, Abteilung Kinderherzchirurgie; Helmut Baumgartner, Gerhard Diller, Klinik und Poliklinik für Erwachsene mit angeborenen (EMAH) und erworbenen Herzfehlern, Universitätsklinikum Münster; Münster. Roswitha Bahle, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Neubrandenburg. Gerald Hofner, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Neudrossenfeld. Stefan Zink, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Nürnberg. Roland Reif, Helmut Singer; Gemeinschaftspraxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie,Allergologie, Asthmatraining, Psychotherapie; Nürnberg. Christoph Parlasca, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Evangelisches Krankenhaus Oberhausen; Oberhausen. Matthias W. Freund, Michael Schumacher, Abteilung Kinderkardiologie an der Klinik für Pädiatrische Pneumologie und Allergologie, Neonatologie und Intensivmedizin, Kinderkardiologie, Klinikum Oldenburg - Elisabeth-Kinderkrankenhaus; Oldenburg. Oliver Dewald, Universitätsklinik für Herzchirurgie, Klinikum Oldenburg; Oldenburg Christine Darrelmann, Reinald Motz, Gemeinschaftspraxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Oldenburg.Olaf Willmann, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Osnabrück.Norbert Schmiedl, Praxis für Kinderkardiologie; Passau.Peter Quick, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Plauen.Dirk Hillebrand, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Schwerpunktpraxis Kinderkardiologie,Angeborene Herzfehler; Pinneberg. Stephan Michele Eiselt, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie und EMAH; Reinbek.Torsten Nekarda, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Agaplesion Diakonieklinikum Rotenburg;Rotenburg. Michael Eberhard, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Rottweil.Georg Baier, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Schwabach. Frank Uhlemann, Zentrum für angeborene Herzfehler, Olgahospital; Stuttgart. Ioannis Tzanavaros, Chirurgie für angeborene Herzfehler/Kinderherzchirurgie, Sana HerzchirurgieStuttgart; Stuttgart. Alexander Beyer, Gudrun Binz, Steffen Hess, Thomas Teufel, Kinderkardiologische Praxis Stuttgart/EMAH-Schwerpunktpraxis; Stuttgart. Ronald-Peter Handke, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Trier. Michael Hofbeck, Renate Kaulitz, Ludger Sieverding, Kinderheilkunde II - Kinderkardiologie, Intensivmedizin und Pulmologie; Christian Schlensak, Thorax-, Herz- und Gefäßchirurgie,Universitätsklinikum Tübingen; Tübingen. Christian Apitz, Michael Kaestner, Sektion Pädiatrische Kardiologie, Universitätskinderklinik Ulm; Ulm. Christoph Kupferschmid, Kinder- und Jugendarztpraxis Ulm, Kinderkardiologie; Ulm. Jürgen Holtvogt, Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie, St. Marienhospital Vechta;Vechta. Carl-Friedrich Wippermann, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie; Walluf. Andreas Heusch, Zentrum für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Abteilung Kinderkardiologie und -pneumologie, Abteilung Kinderkardiologie und -pneumologie, HELIOS Klinikum Wuppertal;Wuppertal. Johannes Wirbelauer, Kinderklinik, Kinderkardiologie/EMAH, Universitätsklinikum Würzburg; Würzburg. Wolfgang Brosi, Praxis für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Kinderkardiologie und –pneumologie, Allergologie, Umweltmedizin, Asthma-, Neurodermitis- und Anaphylaxietrainer; Würzburg.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Competence Network for Congenital Heart Defects, which has received funding from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, grant number 01GI0601 (until 2014), and the DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research; as of 2015).

Conflicts of interest

None.