Mowat–Wilson syndrome is a rare genetic condition due to a mutation in the ZEB2 gene in chromosome 2 in the region 2q22.3;Reference Yamada, Nomura and Yamada 1 in nearly all cases the mutation occurs de novo. Over 50% of patients with Mowat–Wilson syndrome have CHD, and 3.6% have a pulmonary arterial slingReference Ivanovski, Djuric, Giuseppe Caraffi and Santodirocco 2 consisting of an anomalous origin of the left pulmonary artery from the right pulmonary artery and the left pulmonary artery crossing to the left lung between the trachea and the oesophagus.Reference Contro, Miller, White and Potts 3

In early developmental stages, the pulmonary arteries are a composite of arterial buds from the developing sixth aortic arches and capillaries from the pulmonary plexus surrounding the lung buds. The normal central pulmonary artery branches develop from the proximal portion of the ipsilateral sixth aortic arches. In at least some cases of left sixth aortic arch developmental failure, a collateral vessel from the right sixth aortic arch may develop and anastomose with the left sixth aortic arch creating the vascular sling.Reference Erickson, Cocalis and George 4 In most cases, the ductus arteriosus persists in a normal position, indicating that the distal portion of the left sixth aortic arch is not involved.Reference Erickson, Cocalis and George 4 , Reference Kenneth, Gunay and Kurt 5

The ZEB2 gene is widely expressed in the human heart and encodes a protein related to the transforming growth factor beta signalling. The transforming growth factor beta cytokine has an important role in the formation of the aortic arches;Reference Molin, Poelmann and DeRuiter 6 therefore, we underline the importance of considering ZEB2 gene mutations in patients with anomalies of the pulmonary trunk.

Brief case report

A 4-month-old male infant was referred to our clinic for cardiac evaluation. The patient had a history of low birth weight, severe gastroesophageal reflux, partial dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, colpocephaly of the lateral ventricles, left-sided cryptorchidism, and a moderately sized patent ductus arteriosus under medical management. The physical examination revealed square-shaped face with widely spaced eyes, broad nasal bridge, signs of chronic malnutrition, and a grade 2 systolic murmur at the left upper sternal border with radiation to the left axilla. Echocardiogram confirmed a left, moderately sized, patent ductus arteriosus with left atrial and ventricular dilatation. The genetics service considered that the patient met all the clinical diagnostic criteria for Mowat–Wilson syndrome and ordered a complete ZEB2 gene sequence analysis. After considering the potential contribution to the patient’s failure to thrive and the potential risk of developing pulmonary hypertension, the patient was scheduled for ductal ligation. During the procedure, the surgeon noted the left pulmonary arterial sling as an incidental finding, and decided to close the ductus arteriosus leaving the sling unrepaired, awaiting further imaging to evaluate the airway and oesophagus. The patient recovered in the paediatric ICU without significant complications; the gastro-oesophageal reflux was managed with positioning and medications.

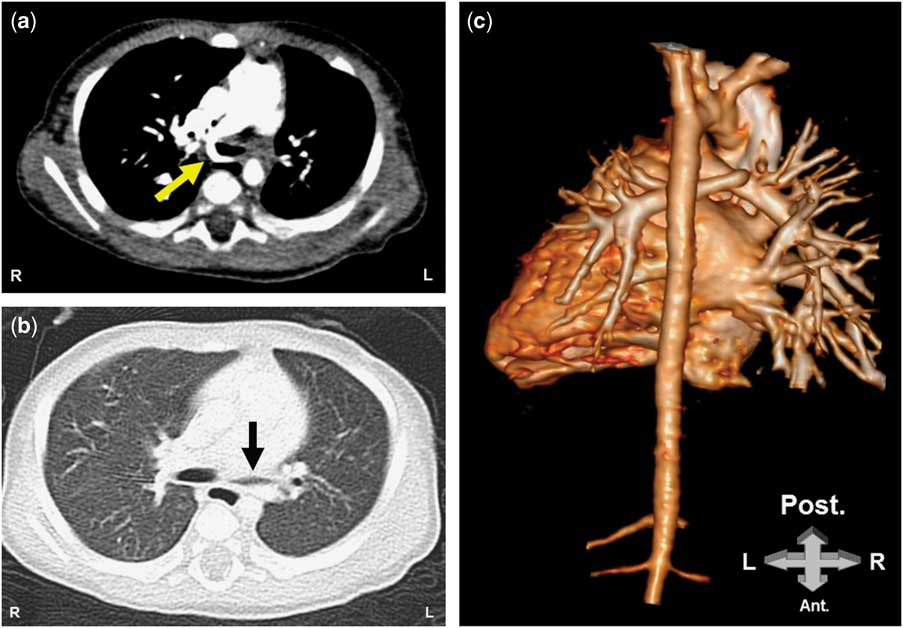

CT with three-dimensional reconstruction (Fig 1) showed the left pulmonary artery emerging from the posterior wall of the right pulmonary artery and crossing to the left between the trachea and the oesophagus, and the lung window (Fig 2b) demonstrated compression of the left main bronchus. We routinely perform fibre-optic bronchoscopy when the CT demonstrates airway compromise. The bronchoscopy (Supplementary video 1) revealed dynamic airway collapse of the left main bronchus with pulsatile compression at the posterior aspect of the carina. Because of the lack of respiratory symptoms and given the surgical risk associated with the patient’s age and the potential delay in neurological milestones, we postponed the surgical repair and followed the child closely as an outpatient to decide the best timing of intervention; at 8 months of age the patient remains without respiratory symptoms.

Figure 1 CT three-dimensional reconstruction of the heart. The left pulmonary artery arises from the right pulmonary artery compressing the trachea and the left main bronchus. The fiberoptic bronchoscopy is shown to reveal the dynamic airway collapse of the carina and the left main bronchus due to the sling.

Figure 2 CT of the chest. A. The left pulmonary artery is arising from the right pulmonary artery and is passing between the trachea and the esophagus (yellow arrow). B. Lung window showing a compression of the left main bronchus. C. 3D reconstruction of the heart from the posterior view revealing the left pulmonary artery emerging from the right pulmonary artery.

Discussion

The pulmonary arterial sling was first described by Glaevecke and Doehle in 1897; its prevalence is estimated at 1 per 17,000 school-aged children.Reference Yu, Liao and Ge 7 The genetic basis of the disease is not well known, but a higher incidence (3.6%) is reported in patients with ZEB2 gene mutations.Reference Yamada, Nomura and Yamada 1 , Reference Ivanovski, Djuric, Giuseppe Caraffi and Santodirocco 2 ZEB2 is a transcriptional repressor of the E-cadherin promoter. During aortic arch formation, the migration of cells is hallmarked by increased N-cadherin expression and down-regulation of E-cadherin. As ZEB2 gene expression is decreased, less down-regulation of E-cadherin probably occurs,Reference Molin, Poelmann and DeRuiter 6 , Reference Lamouille, Xu and Derynck 8 and this may lead to abnormal development of the primitive aortic arches with disruption of the normal development of the left pulmonary artery. Therefore, the diagnosis of Mowat–Wilson syndrome should be considered in patients with a pulmonary arterial sling; conversely, patients with Mowat–Wilson syndrome need careful evaluation of their pulmonary arterial anatomy to rule out a pulmonary arterial sling, to avoid potential delay in the diagnosis.

Our recommendation is that patients with syndromic clinical features and a patent ductus arteriosus should have extensive cardiac investigations to uncover other potential malformations before planning surgery. Owing to the elevated incidence of pulmonary arterial sling in patients with Mowat–Wilson syndrome, we also recommended considering ZEB2 gene mutations in patients with pulmonary arterial malformations.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ruben Acherman, MD, for reviewing the article and providing support and recommendations.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The parents of the patient provided a written and signed consent for the release of clinical information.