An institutional review of cardiac procedure cancellations, within a paediatric cardiology clinic, found that lack of pre-procedural oral screening was an avoidable cause of these cancellations. The implementation of routine oral screening, in the paediatric cardiology setting, with referral to paediatric dentistry for positive screens, has been recommended as a strategy to prevent cardiac procedure cancellations. Reference Coutinho, Maia and Castro1–Reference Yasney and White10

Oral health is important to the systemic health of all children but is of greater importance for children with congenital heart disease (CHD), who are at increased risk for infective endocarditis. Reference Knirsch and Nadal11–Reference Wilson, Taubert and Gewitz13 Invasive procedures and surgical correction of congenital malformations further increase the risk for infective endocarditis in children with CHD. Reference Knirsch and Nadal11,Reference Sun, Lai and Wang12 Infective endocarditis, though rare, has a 30% mortality rate, and an average associated cost in excess of $120,000 per patient. Reference Cahill, Baddour and Habib14

No standardised oral screening tool for paediatric cardiologist use was found within the literature. This result was surprising with current recommendations and guidelines for oral health in CHD children emphasising regular oral health preventive treatment. Reference Yasney and White10,Reference Wilson, Taubert and Gewitz13,Reference Stokes, Richey and Wray15

Poor oral health directly correlates to an increased risk of infective endocarditis. Oral mucosal surfaces, dentition, and gingiva are densely populated by endogenous microflora and are therefore a significant source of transient bacteremia. Reference Wilson, Taubert and Gewitz13 Trauma to periodontal structures can occur during dental extractions or with routine daily activities such as toothbrushing and flossing creating a portal of ingress. Reference Lockhart, Brennan and Thornhill16

Multiple studies have shown a correlation between children with CHD and increased incidence of poor oral health. These studies have used standardised measurements such as the decayed missing and filled teeth indices, simplified oral hygiene index, modified gingival index, and modified plaque index. Reference Garrocho-Rangel, Echavarria-Garcia, Rosales-Berber, Florez-Velazquez and Pozos-Guillen2,Reference Nosrati, Eckert, Kowolik, Ho, Schamberger and Kowolik5,Reference Oliver, Cheung, Hallett and Manton6,Reference Balmer and Bu’Lock17–Reference Hayes and Fasules21 Parental and child factors impacting poor oral health in children with CHD include lack of knowledge regarding the link between infective endocarditis and oral health status, and lax oral health routines due to avoidance of power struggles between parent and child. Reference Balmer and Bu’Lock17,Reference Da Silva, Souza and Cunha22 Paediatric cardiologists’ factors influencing oral health include a lack of knowledge regarding oral health screening Reference Coutinho, Maia and Castro1,Reference Olderog-Hermiston, Nowak and Kanellis23,Reference Oliver, Casas, Judd and Russell24 and the deleterious effects of medications and dietary requirements, for managing CHD, on oral health. Reference Stecksen-Blicks, Rydberg, Nyman, Asplund and Svanberg25 These linked factors are external causes that lead to poor oral health.

Despite numerous studies showing a link between poor oral health in CHD patients and an increased risk for infective endocarditis, few studies have described redesigning oral health screening as a standard of practice in the paediatric cardiology setting. The objective of this quality improvement project was the implementation of a provider-driven, standardised, evidence-based, oral screening tool for CHD invasive treatment candidates aged ≥6 months to <18 years old. Positive screens were referred to dental providers for confirmation. The intervention was intended to reduce risk of infection and preempt case cancellations due to failure to perform clinical evaluation of oral status. Addressing early, the need for treatment management has been shown to decrease cancellations rates. This article outlines the steps of an oral screening program with the goal of dissemination of the implementation process for more paediatric cardiology clinics to adopt similar work redesigns.

Setting

This study took place in an academic paediatric cardiology clinic. The project stakeholders included paediatric cardiologists, the paediatric cardiac surgery team, the cardiology clinic licensed and non-licensed staff, and the paediatric dental clinic providers. The institutional review board deemed the study a quality improvement initiative.

Implementation framework

The quality implementation framework was used for this project. Reference Meyers, Durlak and Wandersman26 A microsystem assessment of the cardiology and dental clinic environment revealed that no linked process existed, to refer children to the dental clinic from the cardiology clinic. Additionally, there was no goal regarding the transfer of knowledge concerning the patient’s oral health within any clinical microsystem including the pre-operative clinic.

Initially, a 12-item questionnaire was used to obtain data on cardiologists’ self-reported beliefs and knowledge toward oral screening. The survey employed binary, Likert, and multiple-choice scales, consistent with the literature (Appendix 1). The goal was to understand how cardiologists think about oral screening with CHD patients. Conversational interviewing after the survey allowed cardiologists to add pertinent narrative on the survey topics. The chances for success in building education material on a topic is improved through navigation of stakeholder beliefs and knowledge. However, education is rarely sufficient in solving multi-dimensional problems.

Theoretical framework of change

Change needs to be managed to be successful. Structures and processes believed to give momentum to the adoption of the oral screening guideline were identified in an effort to anticipate concerns and plan ahead. A comprehensive diagram of the various inputs, activities, outputs, and goals of the study, are included in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Change diagram.

Method

The oral screening tool for this project was created by paediatric cardiology and dental providers experts, using best-practice guidelines. Reference Wilson, Taubert and Gewitz13,27 The oral screening guideline was developed with collaboration among paediatric cardiologists and dental providers. The Guideline Implementability Appraisal tool, Reference Shiffman, Dixon and Brandt28 was used in the creation of the oral screening guideline:

A positive finding of any of the following constitutes a positive oral screen: obvious dental caries, heavy plaque, gingival inflammation, parulis (gingival boil), abscessed teeth, intra-oral pain, or last dental visit >12 months prior. Any positive screen should be referred to a paediatric dental clinic for immediate follow-up.

Provider behavior change

A 30-minute in-service for participating cardiologists, was presented by dental clinic providers. The five photographic objective examples for the oral screening guideline were obvious caries, gingival inflammation, parulis (gingival boils), heavy plaque, and abscessed teeth. From the patient point of view, the two subjective symptoms were intraoral pain and last dental visit >12 months prior. Printed copies of the guideline were provided. Cardiologists were instructed on the redesigned workflow process: electronic health record oral screening documentation, future appointment dental clinic referral process, and real-time immediate referral process to the dental clinic. Providers were given a flyer from the “Lift the Lip” campaign, a quick oral-examination tool. Reference Arrow, Raheb and Miller29

A supportive environment is needed for lasting behaviour change. Reference Francke, Smit, De Veer and Mistiaen30 Electronic health record redesign and support within the physical environment were leveraged to promote the behaviour change of oral screening for all CHD patients. Electronic health record changes included a “hard stop”, for the completion of the oral screening (Fig 2) within the referral order forms for cardiac catheterisation and surgery. An oral screening “dotphrase” template was given to providers for use in their encounter documentation (Fig 2). Visual cues were placed in the physical environment as a reminder to perform the oral screening behaviour. The bi-lingual American Dental Association oral health campaign posters provided a memory-aid. Placards with screening guidelines and dental provider contact information were a trigger at each computer. Basic oral hygiene kits were distributed to each eligible child. The kits contained an informational postcard asking parents to talk to their cardiologist “about the importance of oral hygiene for kids with CHD”.

Dental providers committed to providing ongoing education and support to cardiologists in completing oral screenings. Dental providers were available via pager during cardiology clinic hours and responded, as requested. Clinic medical assistants interviewed patients, regarding last dental visit, as part of the patient intake form and distributed the oral hygiene kits.

Figure 2. Electronic medical record oral screening questions and dotphrase.

Audit and feedback

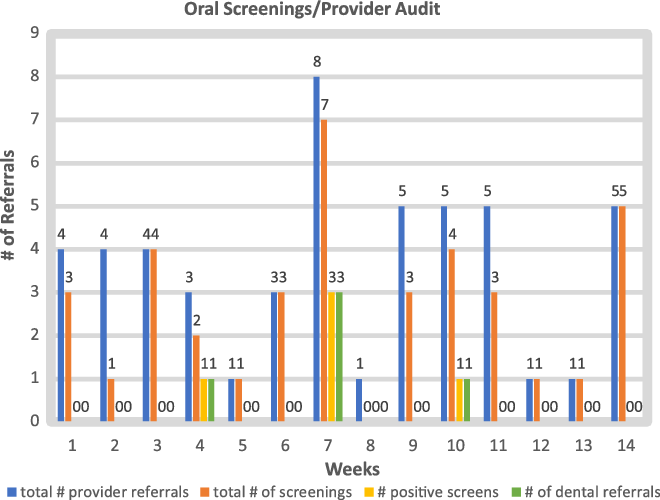

Process assessment strategies included audit and feedback of provider adherence to oral screening. Project leadership summarised frequency and completion data for each provider during the 14-week implementation period. In the 7th week, participating cardiologists received an e-mail reporting the percent of total referrals for cardiac surgery or cardiac catheterisation, in which an oral screening had been completed. Providers with poor compliance were given the opportunity for further education and clarification in order to improve provider adherence. Providers with excellent adherence were also notified and thanked for their outstanding support of the project. All participating providers were encouraged to reach out to project leaders with any questions or suggestions.

Measures

The outcome measure for this project was the adherence to the oral screening guideline for paediatric patients ≥6 months and <18 years of age, with CHD, prior to referral to paediatric interventional catheterisation or congenital cardiac surgery conference. The project was a 14-week “mini-cycle” improvement. 31 Patients less than 6 months of age or >18 years old and children without CHD were excluded. Adherence to oral screening standards was defined as oral assessment documented in the medical record and all positive oral screening assessments referred to dental clinic.

The baseline measurement for oral assessment was determined by retrospective chart audit of all children ≥6 months and <18 years old, referred for cardiac catheterisation or cardiac surgery, from January 2018 to January 2019 (n = 211). Provider encounter notes with physical assessments including language specific to dentition and gingiva were counted as meeting the measure. The audit reviewed each office visit, evaluation and management, that occurred immediately prior to referral to paediatric interventional catheterisation or congenital cardiac surgery conference.

Analysis method

Data was analysed using descriptive statistics. Project data was tracked via weekly electronic reports, compiling all referrals to paediatric interventional catheterisation or congenital cardiac surgery conference, by individual providers. The referral monitoring report detailed the disposition of oral screening questions within the referral order, including any referrals to the dental clinic for positive screens. A Microsoft® Excel, version 16.36 spreadsheet was used to track and analyse data.

Results

There are 23 cardiologists in the department, which includes 19 attending physicians and 4 cardiology fellows. In total, 20 cardiologists (n = 20) participated in the guideline adherence section of the study. In total, 13 (n = 13/19) attending cardiologists participated in the survey and conversational interviews. The survey results revealed that more than half of the surveyed providers were not aware of current recommendations regarding oral health maintenance and infective endocarditis prevention. Conversational interviewing showed a general lack of knowledge among participating providers on the need for regular oral screening of children with CHD. Diagnostic criteria for a positive oral screen and for referral to paediatric dentistry indicated a lack of consistency. Instead, the completion of oral screenings was variable, and when completed was based on the providers’ own practice experience without drawing on the expertise of paediatric dental providers. These quantitative and qualitative results pointed to the need for the education of providers.

Face to face interviews further revealed time management as a screening barrier. Cardiologists within the clinic expressed concern over their ability to add this additional screening element within the given appointment time. Limited time, lack of resources or staff, and work pressure were all factors cited as barriers to oral screening implementation. Key features of the setting needed to be addressed to ensure successful guideline implementation and to support planning for sustainability. Reference Francke, Smit, De Veer and Mistiaen30

A baseline retrospective chart audit from January 2018 to January 2019 (n = 211), of participating cardiologists, showed 47% (n = 100) recorded clinical language specific to dentition and gingiva. During the 14-week implementation period, from April 2019 to July 2019, a total of 78 referrals for cardiac procedures were made by these same participants. In total, 28 of these referrals fell outside of the parameters of this project. Of the remaining 50 in-parameter referrals, 76% (n = 38) received documented oral screenings prior to referral. This showed a 29% increase in documentation of oral screenings prior to referral for cardiac procedures. During the implementation period, 13% of children received a positive oral screen (n = 5) and were appropriately referred to dental providers prior to being scheduled for invasive cardiac procedures.

The number of referrals over the 14-week period averaged six referrals per provider. Individual provider adherence rates varied, with the lowest single participant rate at 20% adherence, and the highest performers at 100% adherence. Total provider compliance was averaged at 70% adherence. There was a less than 1% (0.71%) increase in adherence after the 7-week e-mail providing individualised audit and feedback.

Discussion

Cancellations of paediatric cardiac procedures due to poor oral health results in delay of needed interventions, thereby increasing risk of morbidity and mortality, Reference Yasny and Herlich9 and may create a substantial hardship for the patient and family. Unexpected cancellations create inefficiencies in healthcare delivery which increases resource and labour costs. Reference Galan Perroca, De Carvalho Jericó and Diná Facundin32 Quality improvement is a dynamic process which requires bidirectional input from project leaders and participants and must remain flexible. Multifaceted interventions that feature audit and feedback targeting professional practice with dichotomous outcomes on average show an improvement rate of 5.5% (IQR 0.4–16%). Reference Ivers, Jamtvedt and Flottorp33 Other studies showed improved compliance rates of between 6 and 13% for multi-modal interventions. Reference Grimshaw, Eccles, Walker and Thomas34 This project was able to achieve an increase of 29% in oral screenings during the 14-week implementation period. Provider adherence rates rose rapidly and remained stable throughout the process. More importantly, during the 14-week implementation period, 13% of children (n = 5) with CHD received a positive oral screen and were successfully referred to a paediatric dentist.

Project implementation did encounter unforeseen barriers. The provider educational, oral screening in-service was focussed on the attending physicians in the department, but did not account for physicians in fellowship training, who would be caring for patients and writing referral orders. An educational in-service for the cardiology fellows was scheduled 1 month after the close of the 14-week mini-cycle, due to academic scheduling conflicts. This was done to promote the sustainability of project aims. Another barrier occurred for patients with dental healthcare coverage outside of the academic healthcare system. These patients needed a different referral pathway in order to receive dental care. This barrier is outside of the current scope of this project but does need to be addressed, for the intervention to truly have a positive impact on all patients with positive screens. It is imperative that care be equitable for all patients.

Limitations

This was a mini-cycle improvement quality project of 14 weeks. Due to the small number of referrals per week (n = [1–6]) (Appendix 2), and the small number of total referrals per provider over the intervention period (n = [1–10]), overall adherence rates were easily skewed week-to-week by the performance of a single provider. For this reason, the adherence of all providers was calculated together as an average, to determine the success of the intervention. Although the literature speaks to the success of multi-modal interventions versus single interventions, the combination of interventions chosen is context dependent. The data collected during this project does not illuminate which, if any, parts of the intervention had the greatest impact in changing provider behaviour.

Conclusions

Current literature illustrates that poor oral health increases risk for infective endocarditis. Multiple studies show higher incidence of poor oral health in children with CHD. Implementing best practice remains a complex and challenging task in today’s increasingly complex healthcare environment. This project is evidence of the relative ease by which a standardised oral screening tool can be implemented when a solid framework for implementation is utilised.

Acknowledgements

Thank you, to Professor Lindsay Lancaster Benes, PhD, at the University of Portland’s graduate school of nursing, whose guidance on implementation methods and data analysis was instrumental to the success of this study; and to Kathy Wachtel, RN for her contributions to the quality improvement project work group at OHSU.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The University of Portland, and Oregon Health and Science University, exempted the need for independent review board research approval for this quality improvement, non-interventional study. All patient data was de-identified and anonymised. The study was executed in a manner that is ethical and respects the rights and welfare of the human participants.

Appendix 1 Cardiologist Survey Results

Modified from existing surveys. Reference Coutinho, Maia and Castro1,Reference Oliver, Casas, Judd and Russell35

(N = 13)

-

1. In your opinion, is there any relationship between oral and systemic health?

-

YES = 13/13 (100%)

-

-

2. Do you usually perform an oral examination of your patient?

-

YES = 9/13 (69%) NO = 3/13 (23%) Y/N = 1/13 (7%)

-

-

3. At what age do you assess for oral health of your patients?

-

ALL (AGES) = 3

-

1 YEAR OLD = 3

-

6 MONTHS OLD = 2

-

“starting at 1–2 years old” = 2

-

NO ANSWER = 2

-

“from birth” = 1

-

-

4. Which oral structures do you observe?

-

TEETH = 12

-

GUMS = 6

-

CHEEKS = 1

-

TONGUE = 1

-

PALATE = 1

-

ORAL MUCOSA = 1

-

-

5. Which oral pathologies do you consider relevant when examining your patient?

-

CARIES = 6

-

“PERIDONTAL REDNESS”, “GUM DISEASE”, “GINGIVAL INFLAMMATION” = 5

-

MISSING/BROKEN TEETH = 2

-

PLAQUE = 2

-

ABSCESS = 2

-

“any” = 2

-

NO ANSWER = 2

-

DISCOLORATION OF ENAMEL = 1

-

GINGIVAL HYPERTROPHY = 1

-

MALODOROUS = 1

-

-

6. Do you refer your patients to the DCH 8S Dental Clinic, or another dental provider?

-

YES = 7

-

NO = 3

-

SOMETIMES = 1

-

BOTH = 2

-

NO ANSWER = 1

If other, please specify:

“Only if they need cardiac anesthesia”

“I tell them to see someone, but don’t put in a referral”

“Refer per insurance”

“not had to”[refer to dentist]

-

-

7. When would you advise the parents of your patients that a child should first see a dentist?

-

HANDWRITING ILLEGIBLE = 1

-

6 MONTHS OLD = 3

-

1 YEAR OLD = 3

-

1–2 YEARS OLD = 3

-

DON’T KNOW = 1

-

“If overt caries or infection present” = 1

-

-

8. Do you offer any explanation to your patients/guardians regarding their oral health maintenance?

-

YES = 8

-

NO = 3

-

SOMETIMES = 1

-

NO ANSWER = 1

-

-

9. Do you act on the prevention of infective endocarditis of oral origin?

-

YES = 10

-

NO = 2

-

NO ANSWER = 1

If yes, in what way?

Prescribe SBE prophylaxis = 6

Pt and family counseling regarding oral health = 6

“Make notation about SBE” = 1

Refer to dentist = 1

-

-

10. Does a member of your cardiac team discuss the importance of oral health with the family of your patients?

-

YES = 8

-

NO = 3

-

NO “except if going for cath or surgery” = 1

-

NO ANSWER = 1

-

-

11. How prevalent do you believe poor oral health is in your paediatric CHD patients compared to the healthy paediatric population?

-

“Same” = 6

-

“Don’t know” = 1

-

“Variable, families often don’t know the connection” = 1

-

“Rare” = 1

-

Higher prevalence = 4

-

-

12. Have any of your patients had their surgery or procedure postponed or cancelled, due to dental infection, untreated dental caries, or poor oral health?

-

YES = 7

-

NO = 6

-

Appendix 2 Oral Screenings Disposition by Week