Postural tachycardia syndrome is more frequently being recognised in adolescents and adults.Reference Stewart, Boris and Chelimsky1 However, its pathophysiology is still undefined, despite first being described in 1993.Reference Schondorf, Low and Low2 As has been increasingly seen, patterns are also emerging in what appears to be familial symptoms and associated disorders.Reference Li, Zhang, Hao, Jin and Du3,Reference Posey, Martinez, Lankford, Lupski, Numan and Butler4 We, therefore, sought to characterise the familial associations of various symptoms and disorders in a single-centre practice that manages paediatric patients with postural tachycardia syndrome. Our programme started in 2014 at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, although one author, J.R.B., had been diagnosing and caring for patients since 2007 prior to inception of the programme. During that time, a database collecting clinical information obtained during the course of outpatient care was created to support quality improvement and data analysis, and included all patients diagnosed since 2007 by J.R.B. The database included the patient’s clinical symptoms and history, as well as family history. When the programme for postural tachycardia syndrome started in 2014, a template was created within the electronic health record to more completely and consistently capture these data. The database was subsequently converted to a research database, with approval from and under the auspices of the Institutional Review Board at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Materials and methods

Patients aged 18 years or under at the time of diagnosis were included in the study. In order to avoid the possibility of incomplete histories of familial disorders, and since the template in the electronic health record was generated in 2014, only patients who initially evaluated between 2014 and 2018 were included for evaluation. Diagnosis of postural tachycardia syndrome was made by a combination of a history of chronic orthostatic intolerance, with concomitant symptomatology, physical examination findings, and a heart rate that increased by at least 30 beats/minute on 10-minute stand. Data utilised for this study included the patient’s gender and other baseline demographics, and whether the patient had hypermobile joints with or without hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. Ehlers–Danlos syndrome was diagnosed when the patient was evaluated by a clinical geneticist. Family history was obtained, which included documentation of the affected family member as well as specific disorders. The disorders which we evaluated included the presence of postural tachycardia syndrome, dizziness (specifically as lightheadedness, not vertigo) or syncope, joint hypermobility or Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, and autoimmune disease. The autoimmune disorders included the following: ankylosing spondylitis, coeliac disease, myalgic encephalitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, Crohn’s disease, dermatomyositis or polymyositis, eosinophilic esophagitis, fibromyalgia, mixed connective tissue disorder, psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, autoimmune thyroiditis, and ulcerative colitis. Assessment included whether any family member had the associated disorder, which family member had the associated disorder, and whether more than one family member had the associated disorder.

A waiver of consent was granted by the Institutional Review Board at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, as it would not have been possible to obtain consent for patients seen from significantly older events of care. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel plus the website, Social Science Statistics (https://www.socscistatistics.com/default.aspx). A chi-square for 2 × 2 table for categorical variables was utilised, with significance set at p < 0.05 and Bonferroni correction for multiple tests applied, where applicable. Odds ratios were also calculated, and visualised using forest plots generated by R version 3.6.0 (https://r-project.org).

Results

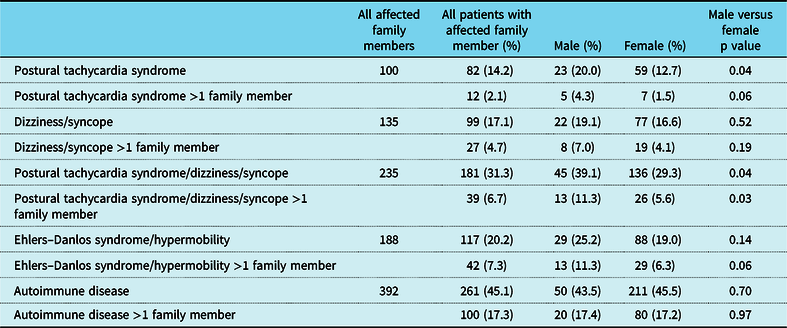

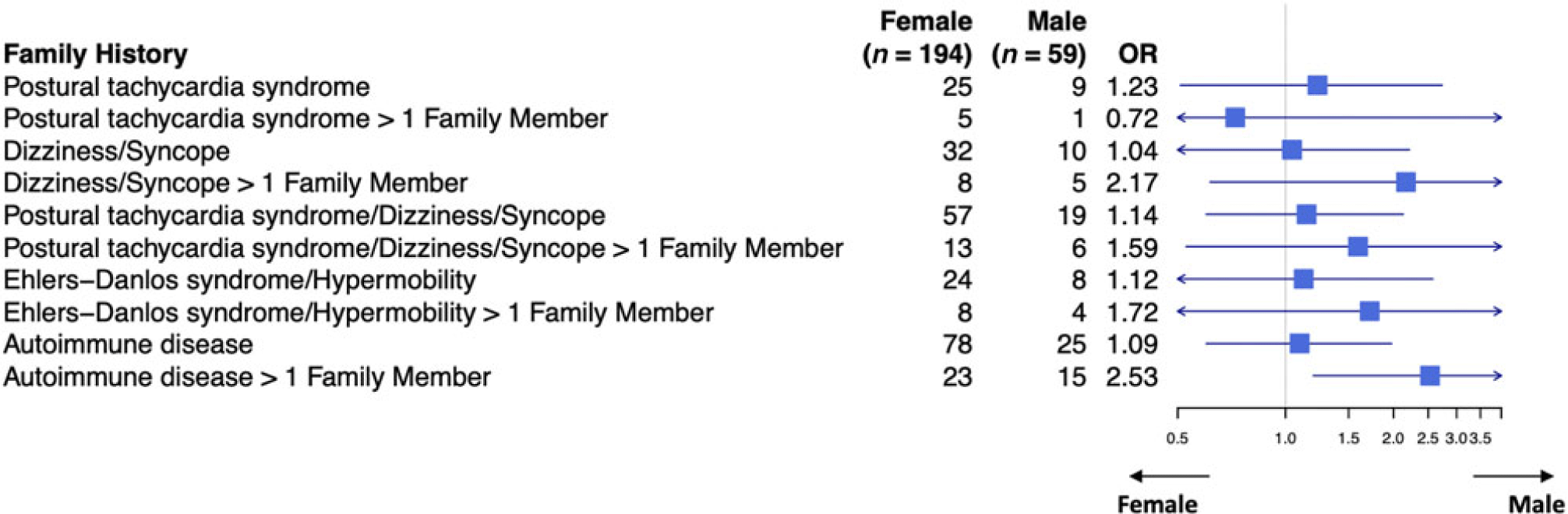

A total of 579 patients met criteria for inclusion in the study. There were 464 females and 115 males (ratio of 4:1). Hypermobility spectrum disorder was diagnosed in 36.3% of the patients, and another 20.0% of the patients had Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, for a total of 56.3% of patients having some aspect of hypermobile joints (Table 1). As shown in previous studies,Reference Boris and Bernadzikowski5,Reference Shaw, Stiles and Bourne6 there was a significant Caucasian predominance (Table 1). As shown in Table 2, we found that 14.2% of patients had a family member with postural tachycardia syndrome; 20% of males had a family member with postural tachycardia syndrome, whereas only 12.7% of females did (p = 0.04). A total of 31.3% of patients had a family member with postural tachycardia syndrome, dizziness, or syncope, with 39.1% of males and 29.3% of females having affected family members (p = 0.04). Approximately one-fifth of patients had a family member with joint hypermobility, and 45.1% of patients had a family member with an autoimmune disorder. Male patients were more than twice as likely to have more than one family member with an autoimmune disorder (Fig 1).

Table 1. Patient demographics

Table 2. Clinical findings in family members of patients with postural tachycardia syndrome

p < 0.05.

Figure 1. Family history of patients with postural tachycardia syndrome.

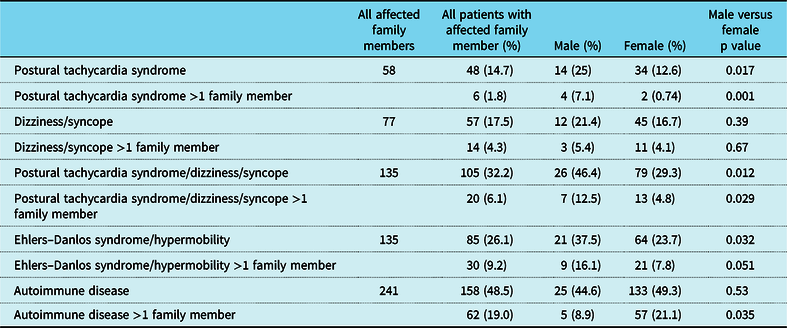

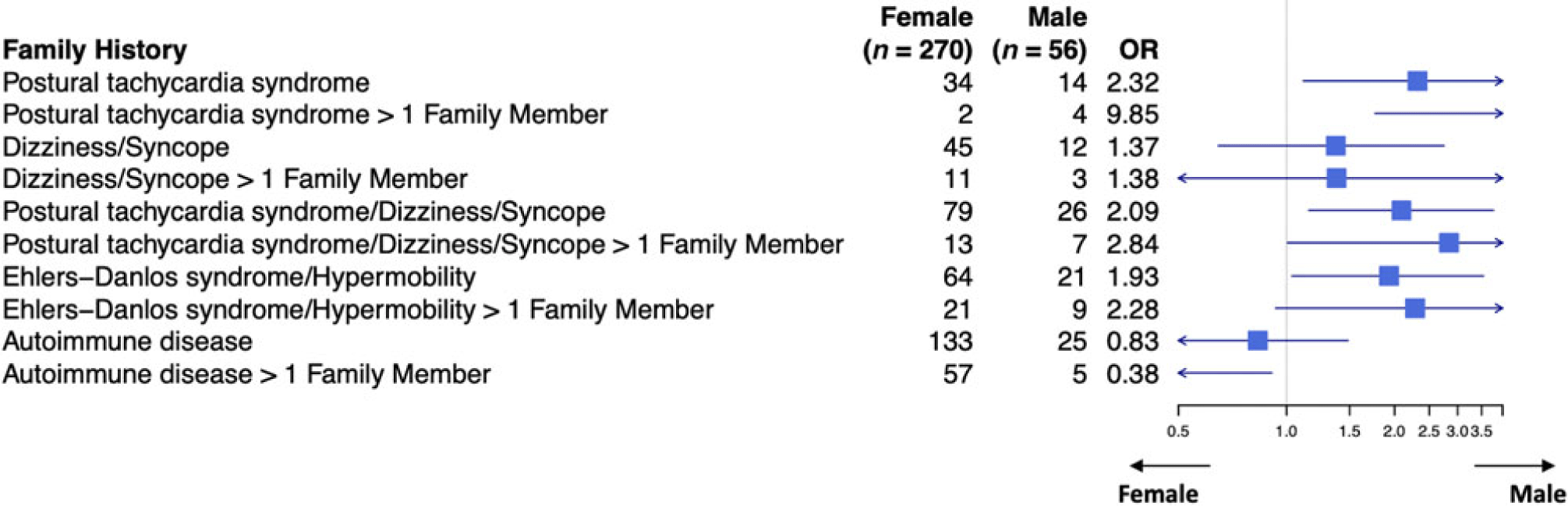

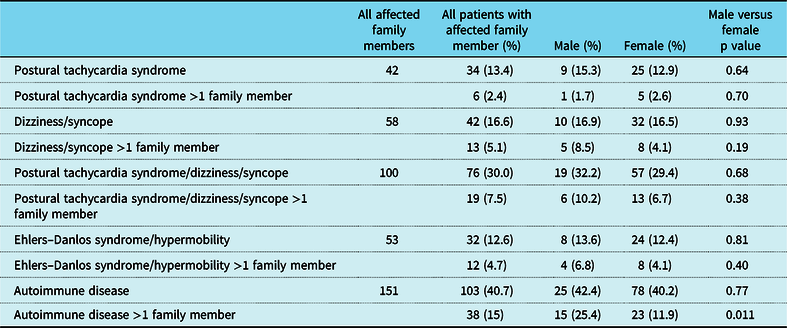

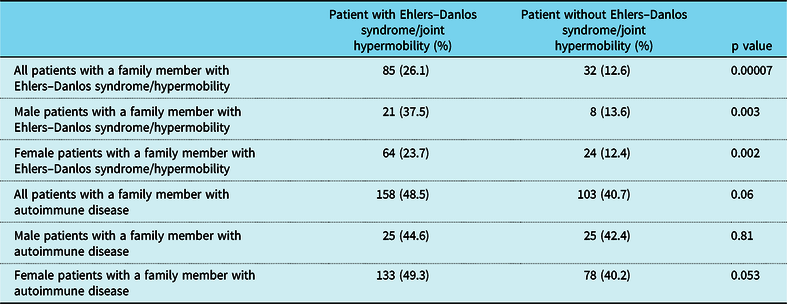

When the patient had a diagnosis of postural tachycardia syndrome as well as hypermobility spectrum disorder or hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, 14.7% of patients had a family member with postural tachycardia syndrome (Table 3). There was a greater preponderance of affected males with family members with postural tachycardia syndrome (25% versus 12.6%, p = 0.017) as well as affected males with more than one family member with postural tachycardia syndrome (7.1% versus 0.74%, p = 0.001). Affected males were twice as likely to have a family member with joint hypermobility (37.5% versus 23.7%, p = 0.032), although affected females were more than twice as likely to have autoimmune disease in more than one family member (21.1% versus 8.9%, p = 0.035, Table 3 and Fig 2). By comparison, patients with postural tachycardia syndrome but without hypermobile joints only demonstrated a single difference between genders, in which males were 2.5 times more likely than females to have more than one family member with autoimmune disease (25.4% versus 11.9%, p = 0.011, Table 4 and Fig 3). In the presence of joint hypermobility, patients of both genders were more likely to have a family member with joint hypermobility (26.1% versus 12.6%, p = 0.00007), as were male patients individually (37.5% versus 13.6%, p = 0.003) and female patients individually (23.7% versus 12.4%, p = 0.002, Table 5). There were no differences between patients with or without hypermobility predicting the presence of autoimmune disorders (Table 5).

Table 3. Clinical findings in family members of patients with postural tachycardia syndrome and hypermobility spectrum disorder/hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

p < 0.05.

Figure 2. Family history of patients with postural tachycardia syndrome and hypermobility spectrum disorder/hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.

Table 4. Clinical findings in family members of patients with postural tachycardia syndrome without hypermobility spectrum disorder/hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

p < 0.05.

Figure 3. Family history of patients with postural tachycardia syndrome without hypermobility spectrum disorder/hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.

Table 5. Comparison of patients with postural tachycardia syndrome with hypermobility spectrum disorder/hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome versus patients with postural tachycardia syndrome without hypermobility spectrum disorder/hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

p < 0.05.

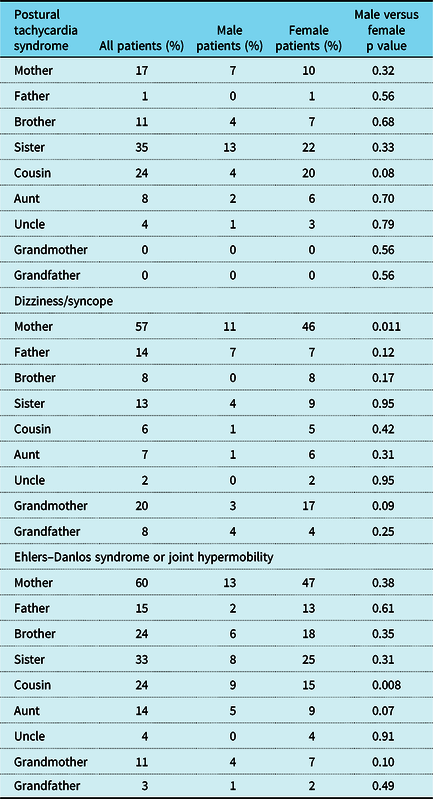

The predominant autoimmune disorders found in family members were autoimmune thyroiditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis (Table 6). However, there were no statistically significant differences between genders. There were also no statistically significant differences between genders based on the affected family member (Table 7).

Table 6. Autoimmune disorders in family members of patients with postural tachycardia syndrome

Table 7. Distribution of associated disorders by specific family members

p < 0.05.

Discussion

Postural tachycardia syndrome, also referred to as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, is a dysautonomia that causes severe disability,Reference McDonald, Koshi, Busner, Kavi and Newton7,Reference Wise, Ross, Brown, Evans and Jason8 and is estimated to occur in up to 3,000,000 persons in the United States of America.Reference Mar and Raj9 Despite having been described 25 years ago,Reference Schondorf, Low and Low2 little is known about the pathophysiology. We had previously shown that nearly 40% of paediatric patients had a putative trigger to onset of symptoms after an infection, concussion, or nontraumatic injury, such as surgery or bony fracture.Reference Boris and Bernadzikowski5 These various insults can activate the immune system, and potentially lead to the genesis of autoimmune disorders. About 5% of patients had a concurrent autoimmune disorder at baseline.Reference Boris and Bernadzikowski5 These findings would fit with the fact that autoantibodies to autonomic receptors have been found in affected patients, although actual causation has not been established.Reference Vernino, Low, Fealey, Stewart, Farrugia and Lennon10–Reference Yu, Li and Murphy13 We also found that just over half of our patients had some aspect of joint hypermobility, with either hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome or hypermobility spectrum disorder.Reference Boris and Bernadzikowski5 This also has been borne out in other studies,Reference Gazit, Nahir, Grahame and Jacob14–Reference Roma, Marsden, De Wandele, Francomano and Rowe16 suggesting a strong association with this disorder, as well. A strong female predominance has been notedReference Schondorf, Low and Low2,Reference Boris and Bernadzikowski5,Reference Shaw, Stiles and Bourne6,Reference Raj17 as has a strong Caucasian predominance.Reference Boris and Bernadzikowski5,Reference Shaw, Stiles and Bourne6 These reports suggest associations but provide no full understanding into the underpinnings of this increasingly recognised disorder.

In this study, we offer additional clues into the context of this disease by looking at specific associated symptoms and disorders present in the family members of these patients. If the estimate of 3,000,000 affected individuals is correct (0.9% of the United States of America population), there is a much higher incidence of postural tachycardia syndrome in family members of affected individuals than in the general population. Furthermore, nearly one-third of the family members have a history of some type of orthostatic intolerance, including postural tachycardia, dizziness, or syncope. This was also seen by Li et al in his single-centre study from China, in which nearly 25% of paediatric patients with postural tachycardia syndrome had a family member with orthostatic intolerance.Reference Li, Zhang, Hao, Jin and Du3 Interestingly, we found that male patients were more likely to have affected family members. The pathophysiology is unknown and the reason for this is not clear, especially in light of the high female predominance. Autosomal dominant transmission with incomplete penetrance of symptoms of autonomic dysfunction, including chronic orthostatic intolerance, dizziness, and syncope, has been reported,Reference Posey, Martinez, Lankford, Lupski, Numan and Butler4 but does not offer sufficient explanation. In a recent case series, three transgender females transitioning to males with the help of parenteral testosterone therapy reported significant clinical improvement in the symptoms associated with their postural tachycardia syndrome, further suggesting influence by sex hormones.Reference Boris, McClain and Bernadzikowski18 Older studies have shown that sex hormones do modulate the way that autonomic neurotransmitters are created, released, and removed, the way that the receptors respond and are distributed, and the way that some hormones convert to that of the opposite gender.Reference Keast19–Reference Hart, Charkoudian and Miller21 Considering the female predominance observed in postural tachycardia syndrome suggests a possible hormonal context and interaction with the autonomic nervous system that is yet undefined.

We also found that a high percentage of family members have autoimmune disorders, approaching 50%. This is a much higher incidence than the 5–8% that is understood to occur in the general population.22 Although these data from the National Institutes of Health about estimated autoimmune involvement in the United States of America are from 2002, they also encompass 24 autoimmune disorders,Reference Jacobsen, Gange, Rose and Graham23 which is significantly more than our study evaluated. It is estimated today that there are more than 80 autoimmune disorders,24 which suggests that our estimate of autoimmune involvement in family members of paediatric patients with postural tachycardia syndrome is actually low, and would be a limitation to this study. Despite this, the occurrence of autoimmune disease in family members in this population, as more than five-fold that of what is noted in the general population, further supports the involvement of an autoimmune basis for at least some component of this disease process.

A potential limitation in this study is comparison of the population in this study to that of our prior study since they derive from the same database. However, they encompass two different time frames, with the present study encompassing patients diagnosed from 2014 to 2018 and the prior study ranging from 2007 to 2016.Reference Boris and Bernadzikowski5 Both studies are quite sizeable (579 patients in the present study versus 708 patients in the prior study); although there may be partial overlap in patients, the difference in the populations is still important to note.

Any study that performs multiple statistical analyses and involves testing of associations for several clinical syndromes may lead to inflated type I error, which is also a limitation for this study. However, as one of the first studies that specifically explores the familial associations of various disorders in paediatric patients with postural tachycardia syndrome, our findings provide initial insight into the pathophysiology of the disorder, which can inform subsequent studies of linked family disorders.

Another limitation in this study is the use of an increase in at least 30 beats/minute as the threshold for diagnosis of postural tachycardia syndrome. This threshold for paediatric patients was increased to at least 40 beats/minute in two consensus publications in 2015Reference Sheldon, Grubb and Olshansky25 and in 2017.Reference Shen, Sheldon and Benditt26 This threshold was determined after study specifically using tilt table testing,Reference Singer, Sletten, Opfer-Gehrking, Brands, Fischer and Low27 although there is early suggestion that tilt table testing induces a higher heart rate response compared to active standing.Reference Plash, Dietrich and Biaggioni28 We had been diagnosing patients at our institution since 2007 with both the prior thresholds and with a 10-minute stand. As our programme started in 2014, we utilised the previous definition. Furthermore, we have recently shown that the symptomatology associated with an increase in heart rate from 30 to 39 beats/minute versus that of 40 or more beats/minute is the same between the two groups of patients.Reference Boris, Huang and Bernadzikowski29 This would suggest that patients with more severe autonomic dysfunction can be discerned from adolescents with typical dizziness and/or syncope with the presence of multiple symptoms that are not simply induced by orthostasis.

This study performs an in-depth evaluation of the associations of several medical disorders and findings seen in the family members of paediatric patients with postural tachycardia syndrome. At minimum, the morbidity and disability that can come with these various conditions are worth a thorough investigation into the family history. This can ensure that the family member gets appropriate medical evaluation and attention, if needed, and may even boost the ability of the family member to better care for the primary patient. But, in a deeper sense, it also gives us further insight into the pathophysiology and possible aetiology, or aetiologies, of postural tachycardia syndrome. Postural tachycardia syndrome has been described as a final common-end pathway for multiple different disorders.Reference Arnold, Ng and Raj30 It is seen with not only the aforementioned co-morbidities, such as concussion, autoimmune disease, and joint hypermobility, as well as being seen more in females and in Caucasians, but it is also associated with such diverse entities as mast cell activation syndrome,Reference Bonamichi-Santos, Yoshimi-Kanamori, Giavina-Bianchi and Aun31 median arcuate ligament syndrome,Reference Ashangari, Suleman and Le32 Chiari malformation,Reference Pasupuleti and Vedre33 cervical instability,Reference Castori, Morlino, Ghibellini, Celletti, Camerota and Grammatico34 cerebrospinal fluid leak,Reference Kato, Hayashi, Arai, Tanahashi, Takahashi and Takao35 and syringomyelia.Reference Nogués, Delorme, Saadia, Heidel and Benarroch36 Once this disorder is better defined and established, we would expect to offer new hypotheses or better explanations as to why these family members experience increased associated medical complications.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Andrea Kennedy of the Cardiac Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for both her creation and friendly, expert updating of the Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome database. The authors would also like to once again thank Andrew Glatz, MD, for his deeply appreciated editorial support in the creation of this manuscript. Finally, the authors would like to thank Arya Boris for her tireless work in data input for the POTS Database.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

No human experimentation was performed in the course of the acquisition of data for this review. The Institutional Review Board of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia granted a waiver of consent, as data were de-identified and collected as part of routine clinical care.