Candida endocarditis is rare during infancy. Successful treatment is best achieved with limited surgery to the valves involved, and systemic administration of antifungal drugs.Reference Luciani, Casali, Viscardi, Marcora, Prioli and Mazzucco1 Total excision of the tricuspid valve in infancy and early childhood is poorly tolerated, and mostly unsuccessful. In this report, we describe a patient who has done well after combined treatment with surgery, antifungal drugs, and pharmacologic management of heart failure, including diuretics and reduction of right ventricular afterload with oxygen, nitric oxide, and sildenafil.

Case report

A female infant was born at 29 weeks of gestation, weighing 1,310 grams at birth. Between the first and third week she was successfully treated for septicaemia due to infection with Klebsiella, Staphylococcus, and Candida. Administration of fluconazole was stopped after 3 weeks in a baby who, at that time, was well. Ultrasonic interrogation of the abdomen, kidneys, and cerebrum was normal. A persistently patent arterial duct became clinically significant at the age of five weeks, and was closed surgically. At a follow-up echocardiogram, a thrombus was seen in the inferior caval vein, albeit causing no obstruction. Subcutaneous heparin was started. When, after two months of treatment, the thrombus remained small, and no obstruction to the flow of blood had become evident, the heparin was stopped. Discharge from hospital followed at the age of three months.

At the age of 4 months, she was readmitted to hospital, and treated for septicaemia due to enterobacter. In addition to full treatment against the sepsis, fluconazole was briefly introduced for five days. On echocardiography, a small insignificant thrombus was still found in the inferior caval vein. She made a full recovery, and was discharged three weeks later. Cultures of blood and urine for fungal infection remained negative during the admission.

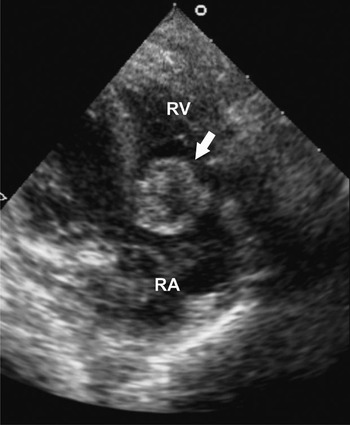

At the age of five months our patient was admitted once more, again septicaemic, and this time with right heart failure. Blood cultures were positive for Candida albicans. On echocardiography, a large thrombus was now seen in the orifice of the tricuspid valve, causing near total obstruction to flow (Fig. 1). Cardiac surgery followed within 24 hours. Under cardiopulmonary bypass, the tricuspid valve was inspected. The valvar orifice was completely obstructed, and its tension apparatus totally destroyed. Reconstruction was not possible. The thrombosed mass was excised, and necrotic remains in the right atrium were removed. Candida albicans was subsequently cultured from the thrombus. Post-operatively, our patient proved difficult to wean from the ventilator. Treatment included maximal inotropic support, diuretics, intravenous heparin, and fluconazole. High concentrations of inspired oxygen, and nitric oxide at 20 parts per million, were introduced to lower the pulmonary pressure. With the addition of sildenafil, at 8 milligrams per kilogram per day, we succeeded in extubating our patient. She was transferred to the ward one week post-operatively, and discharged from the hospital five weeks after admission. Her weight on discharge was 4.5 kilograms. Treatment included oxygen administered via a nasal cannula at night, bumetamide at 0.5 milligrams given thrice daily, sildenafil at 12 milligrams, also thrice daily, fluconazole at 50 milligrams daily, and subcutaneous heparin at 750 international units given once a day. Echocardiographic examination before discharge showed moderate-to-severe insufficiency at the level of the tricuspid valvar orifice, normal antegrade flow across the pulmonary valve, moderate systolic reversal of flow in the hepatic veins, and moderate right atrial and right ventricular dilation (Fig. 2). Echocardiographic abnormalities remained unchanged during subsequent visits. Fluconazole and subcutaneous heparin were stopped after 6 weeks. At the age of 12 months, the patient is now growing well. Half of her daily feeds are given by tube. She is clinically stable, with only mild symptoms of right heart failure.

Figure 1 Apical four-chamber view of an echocardiogram, showing the thrombus in the tricuspid valve (arrow). RA: right atrium; RV: right ventricle.

Figure 2 Apical four-chamber view of an echocardiogram, showing the orifice of the excised tricuspid valve (arrow). Right atrial and right ventricular dilatation. RA: right atrium; RV: right ventricle.

Discussion

Candida endocarditis is a rare event in neonates, accounting for one-twentieth of episodes of endocarditis in this age group.Reference Levy, Shalit and Birk2 It mostly affects the tricuspid and pulmonary valves. Prematurity, treatment with multiple antibiotics, and the use of indwelling central venous catheters, all predispose patients to systemic fungal infections.Reference Levy, Shalit and Birk2 Infants have non-specific symptoms.Reference Ellis, Al-Abdely, Sandridge, Greer and Ventura3 A high index of suspicion, repeated blood cultures, and the use of echocardiography have proven invaluable in diagnosing and following-up of patients. Most patients, after being diagnosed with systemic fungal infections, are successfully treated with antifungal drugs and removal of any offending catheters. Fungal endocarditis, however, is difficult to treat with drugs alone. A combination of antifungal drugs, and limited early corrective surgery of infected valves, have improved survival and represents the treatment of choice.Reference Ellis, Al-Abdely, Sandridge, Greer and Ventura3 Mild-to-moderate valvar insufficiency after surgery is usually well tolerated. Total excision of the tricuspid valve in infants and during early childhood, however, usually leads to severe and untreatable right heart failure.Reference Horvath, Hucin and Slavik4 In adults, excision of the tricuspid valve is better tolerated due to lower pulmonary arterial pressures, and less compliant right ventricles. Replacement of the tricuspid valve at any age remains an uncommon surgical procedure. Only one-fifth of adults will eventually require replacement of the tricuspid valve due to right heart failure.Reference Arbulu and Asfaw5 In this regard, a mechanical prosthesis in the tricuspid position is associated with a high mortality and morbidity, due to thrombotic complications and ingrowth of tissue.Reference Nozar, Anzibar, Picarelli, Tambasco and Leone6 Heterograft valves have been associated with lower operative mortality, but with rapid degeneration and calcification.Reference Nozar, Anzibar, Picarelli, Tambasco and Leone6 Implantation of mitral homografts has been reported from the age of 25 months.Reference Nozar, Anzibar, Picarelli, Tambasco and Leone6 Recent analysis of differences in survival comparing homograft and mechanical valves were inconclusive.Reference Rizzoli, Vendramin, Nesseris, Botto, Guglielmi and Schiavon7 Thus, there is no gold standard. The choice of prosthesis is left to the judgement and experience of the surgeon.

The survival of our patient is exceptional. The combination of treatment of heart failure, and supposed lowering of pulmonary pressures with oxygen, nitric oxide, and sildenafil, proved successful. Sildenafil has been shown to be effective in decreasing pulmonary arterial pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance in neonatal models without systemic hypotension or noticeable adverse affects.Reference Baquero, Soliz, Neira, Venegas and Sola8 The likely absence of pulmonary embolisation in our patient was helpful. The future timing of replacement of the valve, of course will be crucial. Clinical follow-up, supported by echocardiographic and/or resonance imaging measurement of right atrial and ventricular size and function will be important.

In conclusion, our experience shows that survival after total excision of the tricuspid valve is possible, even in infancy. In this regard, the availability of new drugs that lower pulmonary vascular resistance must have been contributory to our success.