Both necrotising enterocolitis and CHD may cause significant morbidity and mortality in neonates. Although these conditions are two distinct disease processes, they seem to be interrelated. In fact, the incidence of necrotising enterocolitis is significantly greater in neonates with CHD than in the normal newborn population, and is highest among patients with single-ventricle physiology, particularly hypoplastic left heart syndrome.Reference McElhinney, Hedrick and Bush 1 Although the exact pathophysiology is not yet clear, prematurity, use of formula feeding, and an altered intestinal microbiota are thought to induce an inflammatory response of the immature intestine.Reference Niemarkt, de Meij and van de Velde 2 Prevalence rates of necrotising enterocolitis ranging from 6.8 to 13% have been reported in infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome,Reference McElhinney, Hedrick and Bush 1 – Reference Jeffries, Wells and Starnes 3 which is markedly higher than rates reported for the entire late preterm/term newborn population.Reference McElhinney, Hedrick and Bush 1 , Reference Palmer, Biffin and Gamsu 4 It is likely that circulatory perturbations, the stress of cardiac surgery, cardiopulmonary bypass, and the baseline elevation of circulating endotoxins and proinflammatory cytokines may play a role in the pathogenesis of necrotising enterocolitis in this uniquely susceptible population.Reference Giannone, Luce and Nankervis 5

The hybrid approach has been developed as an alternative strategy for managing hypoplastic left heart syndrome and other forms of complex CHD.Reference Galantowicz and Cheatham 6 , Reference Galantowicz, Cheatham and Phillips 7 This approach combines surgical – selective banding of pulmonary artery branches – and interventional cardiology – stenting of the ductus arteriosus and balloon atrial septostomy – techniques and shifts the risk of major open-heart surgery and cardiopulmonary bypass to later in infancy. As experience with the hybrid approach continues to grow, outcomes are improving and are now similar to those reported for the Norwood procedure.Reference Galantowicz, Cheatham and Phillips 7 After Norwood procedure, necrotising enterocolitis is associated with prematurity, lower birth weight, and episodes of impaired systemic perfusion or shock.Reference McElhinney, Hedrick and Bush 1 , Reference Jeffries, Wells and Starnes 3

Incidence of gastrointestinal morbidity after the hybrid Stage I approach seems similar to that reported following the Norwood procedure.Reference Luce, Schwartz and Beauseau 8

Although the hybrid approach eliminates the risks for early open-heart surgery and exposure to cardiopulmonary bypass, the question of how the resulting physiology influences the development of a major morbidity such as necrotising enterocolitis remains to be answered. The aim of this study was to document the incidence of necrotising enterocolitis in a cohort of neonates with complex CHD after the hybrid Stage I procedure.

Materials and methods

The charts of 42 consecutive neonates with complex CHD and severe systemic obstruction treated with a hybrid approach at the Mediterranean Pediatric Cardiology Centre from October, 2011 through October, 2014 were reviewed to determine the incidence of necrotising enterocolitis. No patients were excluded from the study.

Necrotising enterocolitis was defined as Bell’s Stage II as reported in the study by Stafford et al.Reference McElhinney, Hedrick and Bush 1

First described in 1978, Bell’s staging of necrotising enterocolitis remains widely used in the clinical, surgical, and research arenas to describe the clinical and radiographic features of necrotising enterocolitis. Stage II necrotising enterocolitis is confirmed by radiographic findings such as dilated bowel loops, pneumatosis intestinalis, and/or portal venous air. By utilising Bell’s Stage II and the above factors – moderate-to-severe necrotising enterocolitis – it is possible to minimise the subjective discrepancy of whether a patient merely had feeding intolerance as opposed to early-stage necrotising enterocolitis.Reference McElhinney, Hedrick and Bush 1 It also allows a more objective measurement – pneumatosis on radiograph – in combination with clinical presentation to assist diagnosis. Radiographs were reviewed separately by a radiologist and by a neonatologist. Pneumatosis had to be agreed upon by both and be present on at least two consecutive films.

We analysed the incidence of necrotising enterocolitis in our population with particular regard to the patient’s post-procedure and ICU course. In detail, we report inotrope use, maximum inotrope score, calculated as dopamine (×1)+dobutamine (×1)+amrinone (×1)+milrinone (×15)+epinephrine (×100)+norepinephrine (×100) as reported by Shore et al,Reference Shore, Nelson and Pearl 9 length of time on ventilator (days), time to initiating enteral feeds (days), time to reaching full enteral feeds (120 ml/kg/day), type of feeding (formula versus human milk), abdominal radiograph findings, necrotising enterocolitis diagnosis, need for abdominal surgery, unexpected re-admission to the ICU for reasons other than scheduled balloon atrial septostomy, need for re-intervention at the aortic arch or ductal stent, length of ICU stay, length of hospitalisation, and mortality. Other pre-procedural factors such as evidence of end-organ compromise – pH, lactate, renal or liver insufficiency defined by very little or no urine output, fluid retention in the abdomen or extremities, increased Blood Urea Nitrogen and creatinine levels, increased urine-specific gravity and osmolality, low blood sodium, very low urine sodium concentration, abnormal prothrombin time, increased blood ammonia levels, low blood albumin, ascites seen on paracentesis – and management strategies – ventilation, subambient oxygen, inotropes, and umbilical vessel catheters – were analysed.

The maximum prostaglandin infusion rate was 0.02 mcg/kg/minute (with a range from 0.01 to 0.02). The drug dose was reduced to the minimum effective dose to obtain unrestrictive patent ductus arteriosus.

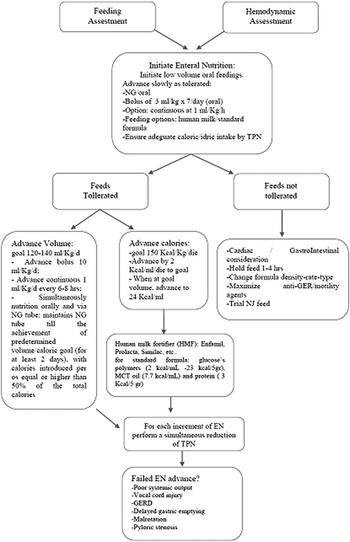

Our dedicated feeding protocol is shown in Figure 1. To reach the target of 150 kcal kg/day, we increased feeds by 2 kcal/oz/dose up to the maximum volume of 120/ml/kg/day, then 24 kcal/oz/dose was added through the human milk fortifier in case of breast feeding or by adding glucose polymers (2 kcal/ml–23 kcal/5 g), medium-chain triglyceride oil (7.7 kcal/ml), and protein (3 kcal/5 g) to the standard formula.

Figure 1 Feeding algorithm. EN=enteral nutrition; GER=gastro-oesophageal reflux; GERD=gastro-oesophageal reflux disease; MCT=medium-chain triglycerides; NG=nasogastric; NJ=nasojejunal; NGT=nasogastric tube; TPN=total parenteral nutrition.

Enteral feeding was started after 6 hours in the case of fast-track extubation, defined as extubation within 6 hours of ending surgery, whereas minimal enteral feeding was given in the case of prolonged mechanical ventilation.

In the majority of patients, enteral nutrition, either human milk or standard formula, was started within 48 hours after the procedure and progressively increased up to a volume of 120 ml/kg/day within 5 days. Nutritional intake was slowly increased, either via a nasogastric tube (continuous at 1 ml/kg/hour) or orally (bolus of 3 ml/kg, seven times per day).Reference Slicker, Hehir and Horsley 10 Adequate caloric and water intakes were always assured by contemporaneous parenteral nutrition. The final volume of 120 ml/kg/day was reached by advancing bolus of 10 ml/kg/day or increasing the continuous infusion rate of 1 ml/kg/day every 6 hours.

Generally, the nutrition delivered orally and that delivered via a nasogastric tube start simultaneously, and the procedure is continued until 50% of the pre-determined volume/caloric intake is achieved and maintained for at least 2 days; the nasogastric tube is then removed for 24 hours in order to verify the spontaneous oral intake of the neonate. Parenteral nutrition is progressively reduced and discontinued.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as mean values and range; frequencies are reported as percentage. The paediatric index of mortality was assessed, and the difference between observed and expected mortality was evaluated by standardised mortality ratio. The frequency of necrotising enterocolitis in our population study was analysed; to compare our data with the frequencies already reported in similar studies, χ2 with odds ratio for risk assessment (by 2×2 CrossTab) or Fisher’s exact tests, where appropriate, were performed.

Results

A total of 42 consecutive patients diagnosed with hypoplastic left heart syndrome and variants underwent hybrid Stage I palliation from October, 2011 through October, 2014. No patients were excluded from the study. The median gestational age was 39 weeks (with a range from 36 to 42). Prenatal diagnosis was made in 76% of the cases (32/42 points), and consequently the births took place at our centre. Postnatal diagnosis was made in 24% of the cases (10/42 points); five patients were referred to our institution in cardiogenic shock. The median age at initiation of the hybrid procedure was 3 days (with a range from 1 to 10), and the median weight was 3.07 kg (with a range from 1.50 to 4.54). Among all, three patients had a genetic syndrome – Trisomy 18, Trisomy 21, and short-arm deletion of chromosome 8.

Cardiac diagnoses included truly hypoplastic left heart syndrome in 24/42 patients (57.1%), with the remaining 18 neonates (42.9%) affected by conditions related to hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Study population characteristics and anatomic variants are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 Demographic data.

AA=aortic atresia; AS=aortic stenosis; AVSD=atrioventricular septal defect; CCTGA=congenitally correct transposition of great arteries; DORV=double-outlet right ventricle; HLHS=hypoplastic left heart syndrome; IAA=interrupted aortic arch; MA=mitral atresia; MS=mitral stenosis; TA=tricuspid atresia; UVH=univentricular heart; VSD=ventricular septal defect

During prostaglandin therapy, all infants were fed regularly. Perioperative management of the neonates included systemic vasodilator therapy with milrinone at a dose of 0.35 mcg/kg/minute. The dose was increased to obtain oxygen saturation of 80–85%, avoiding systemic saturation inferior to 75%. Milrinone was switched to captopril at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day.

Other pre-procedural factors such as evidence of end-organ compromise – pH, lactate, renal, or liver insufficiency – present in 1/42 patients (2.4%) and prematurity (3/42 patients, 7.1%) and management strategies such as ventilation, subambient oxygen, inotropes, umbilical vessel catheters were not associated with the development of necrotising enterocolitis. The median ICU length of stay was 7 days (1–70 days), and the median in-hospital length of stay was 16 days (6–70 days). The median time of mechanical ventilation was 3 days. In all, 11/42 patients (26%) underwent early extubation, and all of them started enteral feeding within 6 hours of extubation. Survival to transfer or discharge after the hybrid Stage I procedure was 83% (35/42). The median inotrope score was 16.5 (with a range from 13.5 to 39).

Unexpected re-admission to the ICU after initial stabilisation and transfer to the cardiology service occurred in two patients due to the need for re-intervention at the aortic arch or neurological complications. There were no re-admissions to the ICU due to necrotising enterocolitis.

In addition, 17% (10/42) developed complications such as myocardial dysfunction (six patients), culture-proven infection in the postoperative period not associated with the diagnosis of necrotising enterocolitis (one patient), and/or neurological complications (three patients).

The standardised mortality ratio of paediatric index of mortality 2 for all patients in the ICU was 0.95 (CI 0.4–2.2). Procedure and post-procedure variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Procedure and post-procedure variables.

BAS=balloon atrial septostomy; PGE=prostaglandins

All patients were fed according to our dedicated feeding protocol. On average, feeding was started in 88% of cases within 6 hour after extubation, whereas in the remainder 11.9% feeding was started within 48 hours from extubation, reaching full enteral feed (120 ml/kg/day) on the 7th postoperative day (with a range from 5 to 10). Commercial formula milk was administered in the majority of patients (83%).

No cases of necrotising enterocolitis occurred (0/42) and no patient experienced Stage I signs of necrotising enterocolitis such as gastric residuals, blood in the stools, or mild abdominal distension. No patient was re-admitted to the hospital after discharge for late onset of necrotising enterocolitis.

Clinical follow-up was extended to the achievement of the second-stage surgery, performed at a mean age of 4 months. In all, 78% (33/42) of patients underwent comprehensive stage to palliation or biventricular repair, 2.3% (1/42) underwent rescue Norwood Stage I at the age of 3 months, and 2.3% (1/42) had interstage death due to myocardial dysfunction.

We found in literature two studies reporting the incidence of necrotising enterocolitis, which was defined by Bell’s Stage II and above, in neonates with hypoplastic left heart syndrome undergoing the hybrid approach: Luce et alReference Luce, Schwartz and Beauseau 8 in 2011 reported an incidence of 8/73, whereas del Castillo et alReference Del Castillo, McCulley and Khemani 11 in 2010 reported an incidence of 17/98. By comparing our data with those reported by Luce, we found a significant difference (p<0.05, Fisher’s exact test; odds ratio 11.1, previous versus ours; statistical difference by Pearson’s χ2 not evaluable due to poor expected frequencies), as well as with those reported by del Castillo (p<0.005, Fisher’s exact test; odds ratio 18.25, previous versus ours, Pearson’s χ2 8.29, p<0.005). Finally, we can report that necrotising enterocolitis frequencies in our population were significantly lower than expected as already reported.

Discussion

The prevalence of necrotising enterocolitis is significantly greater in neonates with CHD than in the normal newborn population and is the highest among patients with single-ventricle physiology, particularly in those patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome.Reference McElhinney, Hedrick and Bush 1 The hybrid palliative treatment of complex CHD and ductus-dependent systemic circulation may help protect patients from certain morbidities associated with neonatal major open-heart surgery and cardiopulmonary bypass. As reported in the literature,Reference Luce, Schwartz and Beauseau 8 the prevalence of moderate-to-severe necrotising enterocolitis found following the hybrid palliation is similar to that previously reported for neonates undergoing the Norwood procedure (6.8–13%). In this study, we report the absence of necrotising enterocolitis in a large cohort of consecutive neonates who underwent hybrid palliation for complex CHD with ductus-dependent systemic circulation as an alternative to neonatal open-heart surgery.

Standardised feeding regimens have been shown to decrease the prevalence of necrotising enterocolitis in premature neonatesReference Del Castillo, McCulley and Khemani 11 , Reference Brown and Sweet 12 and in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome after NorwoodReference Braudis, Curley and Beaupre 13 and/or hybrid treatment. The patients subjected to the postoperative feeding protocol also reached full enteral caloric intake earlier and had a shorter duration of total parenteral nutrition. Feeding regimens are especially important for neonates with single-ventricle physiology, as these patients have been shown to have slower postoperative growth compared with infants with CHD undergoing complete surgical repair.Reference Davis, Davis and Cotman 14 In addition, these patients may benefit from maximum nutrition to prepare them for subsequent surgery. In the preoperative period, complete feeding tolerance is reported during prostaglandin 1 infusion with only occasional reports of necrotising enterocolitis.Reference Luce, Schwartz and Beauseau 8 , Reference Willis, Thureen and Kaufman 15 In the study of Luce et alReference Luce, Schwartz and Beauseau 8 , 64% of the patients received some form of enteral feeding while on prostaglandin 1 with no reports of necrotising enterocolitis in the preoperative period, but 11% of patients experienced necrotising enterocolitis after treatment with the hybrid approach.

The altered systemic blood flow due to impaired right ventricular contractility, tricuspid valve regurgitation, and the tenuous balance between pulmonary and systemic blood flows may explain the higher incidence of necrotising enterocolitis in neonates with hypoplastic left heart syndrome compared with those with other forms of CHD (7.6 versus 2.1%).Reference Davis, Davis and Cotman 14 We believe that the systemic vasodilator therapy,Reference Theilen and Shekerdemian 16 – Reference Furck, Hansen, Uebing, Scheewe, Jung and Kramer 18 incorporated in our perioperative management protocol, could represent a protective factor for necrotising enterocolitis. The use of milrinone in neonates with CHD increases cardiac output with a concurrent effect on splanchnic and cerebral blood flow during the short perioperative time.Reference Nakano, Kado and Shiokawa 19

Although improvement of Doppler mesenteric indices of perfusion with preferential flow to the coeliac artery is reported in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome after the hybrid procedure,Reference Bianchi, Cheung, Phillipos, Aranha-Netto and Joynt 20 the persistence of altered mesenteric perfusion may contribute to the development of necrotising enterocolitis in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. It is reported that the high prevalence of necrotising enterocolitis in neonates with CHD undergoing either the Norwood or the hybrid procedure may be related to underlying changes in the inflammatory state and gut mucosa that could predispose these neonates to develop necrotising enterocolitis.Reference Cozzi, Galantowicz and Cheatham 21 , Reference Harrison, Davis and Reid 22 Increased intestinal permeability has been reported in neonates with hypoplastic left heart syndrome both preoperatively and postoperatively, with the changes in permeability persisting for up to 24 hours after surgery.Reference Lequier, Nikaidoh and Leonard 23 , Reference Malagon, Onkenhout and Klok 24 Cardiac surgery and cardiopulmonary bypass lead to a systemic inflammatory response caused by the contact of blood with foreign surfaces, ischaemia/reperfusion injury, and endotoxin release from the gastrointestinal tract.Reference Giannone, Luce and Nankervis 5 , Reference Cheung, Ho and Cheng 25 In addition, plasma endotoxin levels are elevated in childrenReference Kozik and Tweddell 26 and infantsReference Mou, Haudek and Lequier 27 before cardiac surgery.

In our opinion, it is conceivable that in patients undergoing the hybrid procedure the absence of extracorporeal circulation may contribute to a reduction of intestinal permeability despite predisposing pathophysiology. As previously noted, evidence exists for improvement in the splanchnic circulation after the hybrid approach, but there is no evidence to support a reduction in intestinal permeability.

As techniques have improved and experience has grown, the hybrid Stage I procedure is now a relatively low-impact procedure with the majority (80%) of standard-risk infants being extubated and started on enteral feedings within 24 hours after surgery.Reference Galantowicz and Cheatham 6 In our study cohort, 26% of patients underwent early extubation. Following an initial learning curve, more patients are being extubated early in our more recent experience.

The need for blood transfusion and inotrope use is also minimal, and delayed sternal closure and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation are rare. In comparison with studies of patients undergoing the Norwood procedure, neonates treated with the hybrid procedure are more likely to be fed earlier after surgery.Reference Galantowicz and Cheatham 6

The different definitions of “full enteral feed” do not allow comparisons between the times taken to reach it in the different feeding protocols reported. In addition, our findings are specific to this unique patient population and cannot be generalised to include other patients with other forms of CHD. Therefore, comparative studies on the outcome of different treatment strategies for complex CHD are needed.

As the mortality associated with the hybrid procedure is now similar to that for the Norwood procedure, it is important that a comparison of secondary outcomes and associated morbidities be performed to offer patients the best corrective option. Ideally, this would involve prospective trials at single institutions performing equal numbers of hybrid and Norwood cases, or a multi-institutional trial.

Limitations to the study include the retrospective design, the lack of randomisation, the lack of comparison with a group of Norwood patients, the single-centre design, and the heterogeneous patient population.

Conclusions

The prevalence of necrotising enterocolitis in patients undergoing the hybrid procedure is, in our experience, significantly lower than that expected as already reported in literature for neonates undergoing Norwood surgery and hybrid approach.

Further to the recent success of feeding protocols in infants with complex CHD undergoing the Norwood procedure, the development and implementation of a standardised feeding protocol for infants undergoing the hybrid procedure constitutes, in our experience, a successful strategy if combined with surgery during first few days of life and afterload reduction agents to improve systemic blood flow.

Acknowledgements

Authors’ Contributions: L.M.: data collection, data analysis, and drafting the article; S.M.: data collection and concept/design; S.A.: critical revision of the article; M.B.S. and E.I.: data collection; F.S.I.: critical revision of the article; P.G.: approval of the article.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.