Anyone who has played the murder mystery board game CLUE (Hasbro, Inc, Pawtucket, RI) has heard the phrase naming… “a person, a room, and an object”. If any one player deduces all three correctly, it signifies the end the game. Thus, the names Colonel Mustard, Mrs. White, Professor Plum, Miss Scarlet, Reverend Green, and Mrs. Peacock have achieved immortality, but at the cost of occasional ignominy. So why then should the title of this paper be “Dr Gachet, in the kitchen, with the foxglove”?

As it turns out, there has been much speculation regarding the relationship between Dr. Gachet, a 19th century physician, and Vincent van Gogh, the artist. This speculation stems from the fact that van Gogh was entrusted to the care of Dr. Gachet. However, van Gogh ended up committing suicide, thus bringing to an end the tragic life of this most brilliant art.

Chronology of Vincent van Gogh’s life

Vincent van Gogh was born on 30 March, 1853 in the south of Netherlands to a middle-class family. 1 His father was a minister in the Dutch Reformed church. Van Gogh had an excellent education in the local schools and could speak French and English in addition to his native Dutch. At the age of 16, van Gogh began an apprenticeship at the art gallery named Goupil and Cie in the Hague. Here, van Gogh had the opportunity to view a wide variety of art. Ironically, the gallery for whom he worked specialised in academic art, which centered on classical themes of courage, honor, duty, and fate in allegorical form.

Van Gogh himself was drawn to the increasingly popular landscape painters of the Barbizon school such as Charles-François Daubigny, Jean-François Millet, and Gustave Courbet. These painters depicted images of the French countryside at a time when the cities were becoming increasingly industrialised. The themes of these paintings were to exalt the peasants and labourers who performed back breaking work on a daily basis. These paintings were considered controversial because they replaced gods and heroes at the centerpiece with scenes of the common everyday workers.

After 7 years at the gallery, van Gogh left to pursue a career as a Protestant minister. This decision would follow precisely in his father’s footsteps. He served as an apprentice preacher in Borinage (a coal-mining town near the French border), but when his contract was not renewed, he joined his former congregation and worked in the hard-scrabble coal mines for some time. Here he made numerous sketches of the workers and their conditions during this time.

Starting in 1880, van Gogh committed to a full-time career as an artist. Reference Saltzman2 For the next 5 years he painted in the geographic area where his parents lived along the Belgian/Netherland border. His favourite topic was working class subjects whose bleak conditions he captured in an empathetic fashion, and culminated in the dark, brooding portrait called The Potato Eaters (Fig 1).

Figure 1. The Potato Eaters (1885, oil on canvas, 82 × 114 cm, van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam). This is perhaps the best-known painting from the “Dutch” years.

Van Gogh pursued his artistic career with a religious fervour, which at times bordered on the manic/depressive. He was extraordinarily prolific, churning out over 850 paintings during this 10-year period. He was recognised as an up-coming artist, and had received critical acclaim at several exhibitions in the late 1880s. It is also important to understand that van Gogh sold only one painting during his lifetime, and thus his career was not sustainable of its own accord. His life as an artist was made possible through the generous patronage of his brother Theo, who worked as an art dealer and contributed a portion of his salary to Vincent in exchange for canvasses. This arrangement was viewed by Vincent as an advance payment from a dealer to artist (rather than charity), notwithstanding that none of them were selling. It was also evident that more conventional art such as portraiture had a far better market than the unconventional art that Vincent preferred.

In 1886, van Gogh moved to Paris where he could be in closer contact with his brother Theo. Here he met a group of modern artists including Claude Monet, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Émile Bernard, and Paul Gauguin. These artists were experimenting with the use of much brighter colors, and van Gogh was strongly influenced by these associations. His own paintings underwent a transformation from “dark to light”, although it should be recognised that this transformation had multiple phases. 3 The first phase was the incorporation of much brighter colours than he had previously used in the “Dutch years”, but still most often muted compared to his subsequent work. This is exemplified in the painting View from Theo’s apartment , which he painted in 1887 (Fig 2).

Figure 2. View from Theo’s Apartment (1887, oil on canvas, 45.9 × 38.1 cm, van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam). A representative painting from the Parisian period (1st era of the light period).

It was the artist and Vincent’s friend Paul Gauguin who suggested van Gogh to move to the south of France to experience the brilliant sunshine and colours that are an integral part of that region. Van Gogh moved to Arles in the spring of 1888 and immediately began to paint the local scenes with a vigour and extravagance of colour for which he is now most renown. Although he had used the colour yellow somewhat in his Paris phase, his immersion in the intense sun of southern France now exploded onto his canvases, as in The Sower (Fig 3) and The Harvest (Fig 4).

Figure 3. The Sower (1888, oil on canvas, 32.5 × 40.3 cm, van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam). A representative painting from Arles (2nd era of the light period).

Figure 4. The Harvest (1888, oil on canvas, 73.4 × 91.8 cm, van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam). Representative painting from Arles, with its radiant sun.

It is noteworthy that van Gogh’s depiction of yellow auras or haloes around lights began in 1888. This is evident in his painting Starry night over the Rhone (Fig 5). There are numerous other examples of these yellow haloes, including The Sower, The Night Café (Fig 6), and others. This introduction of auras represents a profound departure from his earlier paintings, not just in the use of yellow but also in the depiction of the shapes.

Figure 5. Starry Night Over the Rhone (1888, oil on canvas, 72.5 × 92 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris). A representative painting from Arles, with a night scene depicting yellow reflections and haloes.

Figure 6. The Night Café (1888, oil on canvas, 72.4 × 92.1 cm, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven) Representative painting from Arles with its bright yellow and haloes around the lights.

In the fall of 1888, Paul Gauguin joined van Gogh in Arles. Gauguin had been somewhat reluctant to make this move, and only agreed to it after Theo promised to pay his expenses. Initially, Gauguin and van Gogh had exhilarating conversations regarding painting and the use of colour. However, the two artists were fundamentally different in the way they went about their work, and these differences soon lead to intense arguments. So just 2 months after his arrival, Gauguin announced that he was returning to Paris. Infuriated, van Gogh sliced off the majority of his left ear, wrapped it in a piece of paper and gave it to a prostitute.

Van Gogh was admitted to the hospital in Arles the next day where he was cared for by Dr. Felix Rey (1867–1932). His brother Theo visited him there in the hospital and found him in a sorry state. He wrote to his fiancé “The people around him realised from his agitation that for the past few days he had been showing symptoms of the most dreadful illness, of madness, and attack of fiévre chaude (translated “extreme agitation”) … Will he remain insane? The doctors think it possible, but daren’t yet say for certain”. Reference Jansen, Luijten and Bakker4 (Letter T30, 28 December, 1888)

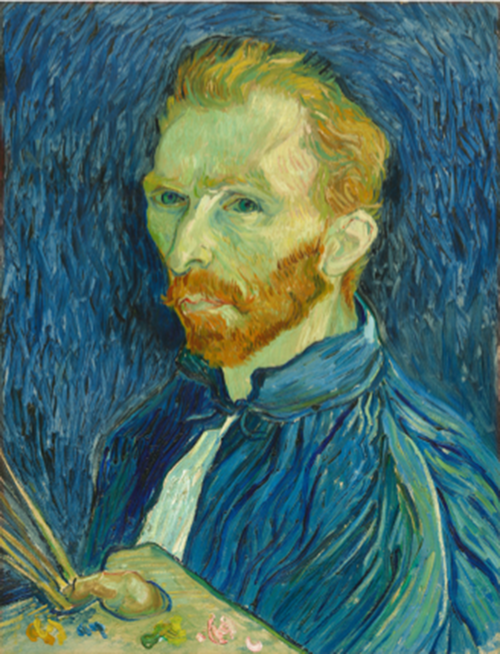

Van Gogh remembered little from this incident, and when he had physically recovered was discharged from the hospital. He continued to have fluctuations in his mental health and voluntarily admitted himself to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole psychiatric hospital located in Saint- Rémy in May of 1889. Reference Bailey5 He was placed under the care of Dr. Théophile Zacharie Peyron (1827–1895). During periods of “wellness”, he was very productive, completing 150 compositions during the year he was hospitalised. It was during this time that he painted the Self-portrait with Palette to demonstrate to the doctor that he was fully sound and capable (Fig 7). There were also severe relapses in his mental illness, as exemplified by episodes when he ingested a significant quantity of paint (in an era when paint would have contained lead).

Figure 7. Self-portrait with Palette (1889, oil on canvas, 57 × 44 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC). Painted to demonstrate to Dr. Peyron that he had fully recovered from his “attack”. This is the only painting in which van Gogh painted himself as an artist, with his artist’s smock and palette.

In May of 1890, van Gogh left the mental hospital in Saint-Rémy and moved to Auvers-sur-Oise. His brother Theo had arranged for him to stay with the aforementioned Dr. Paul Gachet. The doctor was an amateur artist himself, and had the previous year helped the artist Camille Pissarro. However, he was not entirely well himself. After 2 days at Auvers, van Gogh wrote a letter to his brother stating “I think that we must not count of Dr. Gachet at all. First of all, he is sicker than I am, I think, or shall we say just as much, so that’s that. Now when one blind man leads another blind man, don’t they both fall into the ditch?” Reference Jansen, Luijten and Bakker4 (Letter RM 20, 24 May, 1890).

Van Gogh’s impression of Dr. Gachet improved over time, and they became friends. Reference Costello and Storr6 The doctor encouraged van Gogh to put his efforts into painting as he perceived that this would provide a path towards wellness. Dr. Gachet may have also viewed van Gogh as somewhat of an artistic rival, since van Gogh had sold just one more painting (i.e., one) than the doctor at the time of their acquaintance ( The Red Vineyard, painted in 1888 in Arles, Fig 8). Thus, there was an inherent conflict in their relationship, just as there was between Theo and Vincent as the result of Theo’s financial support.

Figure 8. The Red Vineyard (1888, oil on canvas, 75 × 93 cm, Pushkin Museum, Moscow). The only painting that was sold during van Gogh’s lifetime.

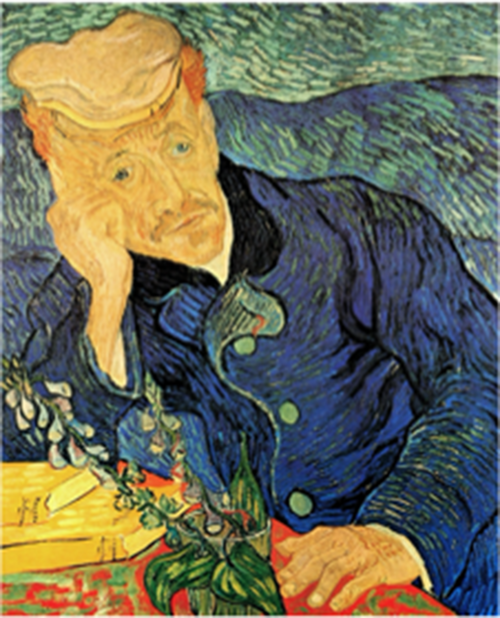

In June of 1890, van Gogh painted A Portrait of Dr. Gachet (Fig 9). The painting depicts the doctor seated at the kitchen table. His head rests on his right hand, and he has a melancholic expression. Reference Aronson and Ramachandran7 There is a spray of foxglove in the foreground, perhaps an attribution to the doctor’s profession. Two books are sitting on the table, and even the books are depressing in content. Germine Lacerteux is the story of a debauched servant who dies in the workhouse, and Manette Salomon is the story of four unsuccessful painters. The background colours of various shades of blue add to the somber mood. Van Gogh wrote to his sister “I’ve done the portrait of M. Gachet with a melancholy expression, which might seem like a grimace to those who see it. Sad but gentle, yet clear and intelligent”. Reference Jansen, Luijten and Bakker4 (Letter 886, June 13, 1890)

Figure 9. Portrait of Doctor Gachet (1890, oil on canvas, 66 × 57 cm, private collection). Doctor Gachet had promised Theo that he would cure van Gogh. He is portrayed by the artist as a melancholic soul, seated at the kitchen table. He is holding foxglove, which he grew in his own backyard herbal garden.

During the 70 days that van Gogh lived at Auvers-sur-Oise, he painted no less than 72 paintings as well as possibly his only etching (also of Dr. Gachet). Working at this feverish pace, one might think that many of these paintings would be hurriedly done and not of the same quality. However, nothing further could be from the truth. The paintings that he produced during this short interval are resident to museums throughout the world. Tragically, in spite of this extremely productive time, his illness and sense of despair got the best of him. On 27 July, 1890, van Gogh shot himself in the chest with a revolver. He initially survived his injuries, and the local physician, Dr. Joseph Mazery, was called along with Dr. Gachet. Vincent van Gogh died from his injuries on July 29th at the age of 37 and was buried the following day.

Van Gogh’s mental health disorder

Vincent van Gogh’s life was characterised by tragedy, loneliness, depression, and ultimate self-destruction. In later life, he would go through periods where he was completely lucent, productive, and able to maintain a semblance of normal relationships. These would be followed by episodic “attacks”, during which he was completely debilitated, irrational, had visual and auditory hallucinations, and at times made attempts at self-harm. It is interesting that the physicians who cared for van Gogh recognised quite clearly that he did not have the classic signs of “madness”, since he would invariably have a complete recovery following these attacks.

In retrospect, it is very likely that van Gogh suffered from temporal lobe epilepsy. Reference Bailey5,Reference Blumer8,Reference Doiteau and Leroy9 The contemporary physicians of van Gogh astutely made this diagnosis of epilepsy, and so this is not just a modern-day view. Dr. Felix Rey was an intern at the hospital and just 23 years old when he took care of van Gogh after the “ear incident” in December 1888. He was well-schooled in the symptoms of epilepsy, and after observing van Gogh’s state of mind, prescribed potassium bromide. Within days, van Gogh recovered from his psychotic state. Potassium bromide had been discovered in the mid-19th century to have excellent properties in suppressing seizures, and was widely used through most of the 20th century until it was displaced by modern-day medications (it is still commonly used in veterinary medicine). At the end of this period of recovery, van Gogh wrote to Theo stating “The intolerable hallucinations have ceased, in fact have diminished to a simple nightmare, as a result of taking potassium bromide”. Reference Jansen, Luijten and Bakker4 (Letter 743, 28 January, 1889).

Dr. Peyron was also aware that the absinthe van Gogh often consumed may have played a contributing role in promoting his seizures. Absinthe was a popular liqueur in the 19th century, and the active ingredient (thujone) is both an epileptogenic and can cause auditory and visual hallucinations. Thujone was used in the 1920s and 1930s to induce seizures for treatment of schizophrenia, but it was eventually outlawed due to its toxicity. During the summer of 1888, van Gogh would eat very little throughout the day and then drink brandy and absinthe excessively at night. In our modern-day interpretation, it is likely that van Gogh had a temporal lobe epileptic lesion that was further unmasked by his consumption of the epileptogenic absinthe.

Dozens of other diagnoses have been proposed by a myriad of physicians over the 130 years since his death. Reference Arenberg, Countryman, Bernstein and Shambaugh10,Reference Arnold11 In addition to his underlying mental health disorder, it has been speculated that the ingestion of various prescribed and unprescribed medications may have exacerbated his frequently debilitating mental disorder including excessive alcohol consumption, digitalis (foxglove) toxicity, Reference Greuner12 absinthe, Reference Arnold13 and lead. The dramatic fluctuations in his mental state were extreme, and it remains uncertain how much of this was the result of the disease and how much was attributable to an inadequate diet compounded by the ingestion of numerous toxic substances.

Xanthopsia and van Gogh

Another area of speculation regarding Vincent van Gogh’s career is whether he suffered from xanthopsia. Reference Arnold and Loftus14 Xanthopsia is an overriding yellow bias in vision, and can be caused by a variety of drugs including santonin, digitalis (the active ingredient in foxglove), phenacetin, ether, chromic and picric acids, thujone (in the absinthe that he drank), and lead (in the paints that he ate during his attacks). The idea that van Gogh may have suffered from digitalis toxicity as the explanation for his xanthopsia was first proposed by Lee in 1981. Reference Lee15 He suggested that the yellow preference and auras induced by digoxin toxicity were considered a positive addition to the paintings by the artist, and therefore he continued to paint with a yellow dominance even after the side effects were no longer present. In other words, this theory did not require van Gogh to be digoxin toxic indefinitely, but simply for a long enough period of time that he can to appreciate this effect. There have subsequently been numerous articles written weighing in on the possibilities and improbabilities of this hypothesis.

In 1785, Dr. William Withering (1741–1799) identified the active ingredient in foxglove as digoxin (Fig 10). Dr. Withering had observed patients with edema secondary to heart failure who had improved with the administration of an herbal remedy. Reference Withering16 Using his training as a botanist and chemist, he isolated the active ingredient to a chemical contained in the foxglove leaf, and it was called “digoxin” (after the plant’s scientific name digitalis purpurea). Dr. Withering subsequently published his paper on the clinical use of foxglove to treat heart failure. In addition, he also recognised and described the signs and symptoms of digoxin toxicity. Digoxin has a relatively narrow therapeutic range, and even in modern times, digoxin toxicity is not uncommon. Reference Kanji and MacLean17 In total, 15% of patients with digoxin toxicity have xanthopsia, and a much higher incidence of colour vision deficiency. Reference Lawrenson, Kelly, Lawrenson and Birch18 Brewing a foxglove extract from the leaves could result in a wide variety of potencies, and thus one can conceive that digoxin toxicity was more common then than now. Reference Ramlakhan and Fletcher19

Figure 10. Dr. William Withering (Carl Fredrik von Breda, 1792, oil on canvas, 125 × 101 cm, Swedish NationalMuseum, Stockholm) Dr. Withering was an English physician who first identified digoxin as the active ingredient in foxglove. By the 19th century, foxglove was used by homeopathists for treating more than 70 conditions.

By the last quarter of the 19th century in France, foxglove was used by a significant portion of the population. Foxglove leaves were used to make tea, just as we now use Echinacea. Medical references list more than 70 different maladies for which foxglove was recommended as a treatment. Reference Aronson20 It was an era when homeopathy was extremely popular, and foxglove was used to treat seizures (for which it did not have an effect), depression, mental illness, headache, nausea, and vomiting, all of which van Gogh had from time-to-time. Thus, it would almost be shocking if one of van Gogh’s physicians had not recommended or prescribed foxglove.

If we assume that foxglove as a “medication” would have only been prescribed to van Gogh by a physician, then we have just three names that are on that list. The aforementioned Dr. Felix Rey took care of van Gogh in the medical hospital in Arles after van Gogh sliced off his ear. Dr. Rey tended to the wound, prescribed potassium bromide for treatment of his seizures, but soon thereafter discharged his patient. Since Dr. Rey had faith in potassium bromide for the treatment of seizures, it is unlikely that he would have added foxglove to the mix.

The second doctor involved in van Gogh’s care was Dr. Théophile Peyron, who had overseen the asylum at St. Rémy for 15 years and was a senior physician. Dr. Peyron took a personal interest in van Gogh, as he could see that there was a unique talent in this troubled person. He often would facilitate the work of van Gogh by providing an escort when the artist wanted to leave the grounds of the asylum to paint. He also was tasked with treating van Gogh’s mental condition, which he thought was attributable to intermittent epileptic seizures. Epilepsy was one of the indications for foxglove preparations, and so it is reasonable to conjecture that Dr. Peyron treated van Gogh with a locally made herbal concoction containing foxglove. The contemporaneous letters between van Gogh and his brother allude to the fact that they were hopeful that this “treatment” would be effective in at least reducing the impact of the intermittent and debilitating attacks. Unfortunately, there are no indications as to the exact ingredient or remedy in any of the voluminous letters between brothers. It should be noted that van Gogh had at least six “attacks” during his stay in St. Rémy, and thus it is also possible that the ingredients of his cure actually made him worse. Nevertheless, in the ledger book of the asylum on the date of his discharge, there appears the word “guérison” (meaning healed or cured).

The third doctor who took care of van Gogh was Dr. Paul Gachet. Dr. Gachet had studied medicine in Paris and Montpellier, and had written a thesis entitled “Étude sur la mélancholie”. Reference Gachet21 He had moved to Auvers in 1872 and was a strong advocate of homeopathy. He had a garden in his backyard where he grew his own flowers and herbs, made herbal remedies, and sold them to the patients under his care. Amongst the historical artifacts that survived from his estate were his pharmacy kits (with his name on them), which had been stored in the Musée d’Histoire de la Médecine in Paris, René Descartes University. On 6th and 7th of December, 2004, a detailed analysis was conducted of the kits. 22 One was a travelling kit containing 12 remedies, and the other a larger box containing 98 remedies in glass tubes sealed with cork. The names and potency of the drug were handwritten on the top of the corks. In total, the entire pharmacy would have contained between 400 and 500 tubes in 4 or 5 boxes. This provides some attestation for the devotion to homeopathy that this physician utilised.

Dr. Gachet had befriended many of the Parisian artists and provided treatments to Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, and Claude Monet in exchange for paintings. Another patient was Pissarro, who raved about his cures. Many of these artists painted scenes of Auvers, including the doctors house and garden. Thus, Dr. Gachet had established himself as someone who was sympathetic to artists and could help them with their woes.

Theo van Gogh met with Dr. Gachet on 29 March, 1890 to interview him and see if the doctor might be able to help his brother Vincent. Theo’s letter to Vincent reads “When I told him how your crises came about, he said to me that he didn’t believe it had anything to do with madness, and that if it was what he thought, he could guarantee your recovery”. Reference Jansen, Luijten and Bakker4 (Letter T31, 29 March, 1890). These are strangely confident words coming from someone who themselves struggled with sadness and depression. It also suggests that Gachet fully intended some form of treatment. One is inclined to believe this would be a homeopathic remedy, as this is what he believed in and practiced. He may have even conceived that this treatment could be provided in exchange for some of van Gogh’s paintings, as he had done with other artists. Thus, it is very likely that van Gogh was enrolled in a homeopathic treatment on his arrival to Auvers, perhaps incentivised by this dubious arrangement.

It is important to note that there exists no documentation regarding the specifics of any treatment provided by Dr. Gachet to van Gogh. Dr. Gachet served as both physician and pharmacist, and thus there were no written prescriptions to a pharmacy to provide documentation as would occur today. One could imagine that Dr. Gachet’s office records would provide some extremely valuable information on the subject, but these medical records were deliberately destroyed by his children following his death. The most lasting documentation are the letters between Vincent van Gogh and his brother Theo, sister-in-law, mother, and many others. Innumerable scholars have pored over these letters and there is no hint of any formal treatment with a medication. A skeptic might interpret this absence of information as indicating that no treatment occurred at all, but there is also an absence of information for artists who we know were treated by Dr. Gachet. In the end, one must only speculate that the inclusion of foxglove in the painting had some important meaning.

Relationship between colour and medication

Many depictions of van Gogh’s life have described the transition from dark (the Dutch period, 1880–1886) to light (French period, 1886–1890) as if it were a switch that was suddenly turned on. There is no doubt that the colours in his palette changed dramatically in 1886 when he moved to Paris, and most notably with the addition of the colour yellow. Countless papers have documented the presence or absence of the colour yellow and then tried to link this (or in some cases refute this) with digoxin toxicity. However, it is a vast oversimplification to simply look at the use of yellow as a binomial function during this 4-year time period. The authors of this paper would suggest that van Gogh’s painting during the French period should be sub-divided into four separate eras.

The first of these four eras would be the time that he spent in Paris, which was 1886–1887. During this time period, van Gogh began to incorporate the colour yellow, but it was used in a muted way. The painting View from Theo’s Apartment (Fig 3) is representative, and shows the use of brighter colours including some yellow. It is also evident that there are no haloes or auras in these paintings. This time period in Paris was spent in close proximity to his brother Theo and many other friends, and it can be assumed that van Gogh was being looked after. Specifically, one can infer from the available information that he was eating reasonably well, was not drinking alcohol of absinthe excessively and was not taking any herbal remedies or medications. Thus, the Parisian paintings are notable for the absence of any influence of drugs or medications.

The second era is essentially the calendar year of 1888. In February of that year, van Gogh moved to Arles in the south of France, encouraged to do so by his friend Gauguin. Gauguin thought that van Gogh would thrive under the brilliant sunlight of Provence. This also meant that van Gogh was separated from his circle of family and friends present in Paris. In the absence of that stabilising influence, van Gogh begins a lifestyle of eating little and overindulging in alcohol and absinthe. He subsequently wrote to Theo and described that “it is true that to attain the high yellow note that I attained last summer, I really had to be pretty well keyed up” Reference Jansen, Luijten and Bakker4 (letter 752, 24 March, 1889). Now if I recover, I must begin again, and I shall not again reach the heights to which sickness partially led me”. Reference Jansen, Luijten and Bakker4 (letter 735, 9 January, 1889). The paintings produced during the spring, summer, and fall of 1888 heralded a complete departure from his paintings in Paris, with an intensity of yellow that was new. Examples of these works include The Sower (Fig 3), The Harvest (Fig 4), Starry Night Over the Rhone (Fig 5), The Night Café (Fig 6), Fishing Boats on the Beach of Les Saintes, and Still Life: Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers. While van Gogh perceived that the frenzy he had induced had led to an elevation in his art, it also came at a cost. In December, he had a complete mental collapse leading up to the “ear incident”, followed by two more “attacks” in early 1889. The combination of intense sun, too little food, and too much alcohol and absinthe provided the substrate for some of van Gogh’s most brilliant and well-known art.

The third era is the year that van Gogh lived in the asylum at St. Rémy, from May 1889 to May 1890. Upon admission to the asylum, van Gogh went from the completely unregulated life that he had led in 1888 to the completely regulated schedule of an institution. This included the provision of three meals a day, something that had been sorely lacking the previous year. Commitment in the asylum also meant that van Gogh no longer had access to alcohol or absinthe. Van Gogh soon recognised that the excessive alcohol he had been consuming had almost certainly been doing him harm. Van Gogh and his brother were hopeful that the treatments being offered by Dr. Peyron would be beneficial. The doctor had made the diagnosis of epilepsy, and presumably the treatments were directed at mitigating the manifestations of this problem. In the late 19th century, the medical treatment of epilepsy was not all that scientific, and may have included herbal remedies such as foxglove or the newly discovered potassium bromide. In a book published in 1928, Drs. Doiteaux and Leroy suggest on page 64 that the bromide started under the care of Dr. Rey may have been continued by Dr. Peyron at St. Rémy. Reference Doiteau and Leroy9 However, they admit in the same paragraph that “we cannot certify this”. Dr. Leroy was the medical director at St. Rémy from 1919 to 1964 and so had unique (monopolistic) access to the medical records of van Gogh that to this day have never been made public. In the end, we are left with no specific records van Gogh’s treatment during this time period, either from the hospital or from his letters and correspondence.

The paintings of van Gogh undergo another transformation during this 1-year stint in the asylum. The yellows become more vibrant, even pulsating, and the sun, the moon, and the stars have haloes. During this 1 year, van Gogh produces 150 paintings, including Starry Night, (Fig 11), Olive Trees with Yellow Sky and Sun (Fig 12), The Thresher, The Reaper, multiple versions of The Sower, The Hospital in Arles, The Garden at St. Remy, and Enclosed Field with Peasant. These are the paintings that will make van Gogh famous posthumously, and the paintings that have been exhibited all of over the world. One can only speculate on the role that his “treatments” played in shaping his vision, his thoughts, and his perceptions. Sadly, van Gogh was to sustain a severe attack on the anniversary of the ear incident followed by three more attacks in the winter/spring of 1890 resulting in debilitation. Whatever herbal remedies may have been prescribed by Dr. Peyron in St. Rémy apparently did not reduce the risk of seizures, and perhaps served to increase the risk of recurrent attacks.

Figure 11. Starry Night (1889, oil on canvas, 74 × 92 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York). From St. Remy. Similar to Starry Night Over the Rhone, the painting depicts a night scene with bright yellow and haloes. (3rd era of light period).

Figure 12. Olive Trees with Yellow Sky and Sun (1889, oil on canvas, 74 × 93 cm, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis). From St. Remy.

The fourth and final era of van Gogh’s light period was the 70 days at Auvers. Here, he was under the care of Dr. Gachet, who had boasted that he could cure the man. Presumably, whatever herbal remedies he had taken at St. Rémy were stopped (particularly in light of the recurrent attacks), and a new regimen prescribed. It is interesting to note van Gogh did not sustain an attack (seizure) during his time in Auvers, thus lending support that his medical regimen had been changed.

The paintings that van Gogh produced in Auvers take on yet another manifestation. The dominant colour changes from yellow to green, the yellows are quieter, and the haloes are gone. In addition to the Portrait of Dr. Gachet (Fig 9), other paintings include The Church at Auvers (Fig 13), The White House at Night, and Irises. His last series of paintings (in mid-to-late July) in Auvers focussed on the wheatfield near Auvers, including Wheatfield UnderThunder Clouds (Fig 14) and Wheatfield with Crows (Fig 15). On the 27th (as the story has been told), van Gogh borrowed a pistol from the owner of the Ravoux Inn purportedly on the pretext of scaring away the crows, which he claimed were coming too close to his canvases. However, instead of scaring away crows, he walked out into the wheatfield that he had been painting and shot himself. Whatever treatment was offered up by Dr. Gachet to effect a “cure” for van Gogh, in the end van Gogh opted to take his own life, forever bringing in to question the quality of the cure.

Figure 13. The Church at Auvers (1890, oil on canvas, 93 × 74.5 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Painting from June, 1890 in Auvers (4th era of light period).

Figure 14. Wheatfield Under Thunder Clouds (1890, oil on canvas, 50.4 × 101.3 cm, van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam). In Auvers, mid-July, 1890.

Figure 15. Wheatfield with Crows (1890, oil on canvas, 50.5 × 103 cm, van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam). This painting has often been stated as van Gogh’s last painting. However, today it is thought that it was executed on July 10th, or two and a half weeks prior to his death.

Conspiracy theories

There are countless conspiracy theories that have arisen regarding the life and death of Vincent van Gogh. In 1947, in what would be the first van Gogh exhibit in Paris following the War. Antonin Artaud, a writer, actor, and producer, was asked to write a commentary to accompany the show. Reference Artaud23 His comments were published in an article titled “van Gogh le suicide de la société”, or the man suicided by society. His premise was that a society largely unsympathetic to people with mental disturbances had been the cause of van Gogh’s death. More specifically, he laid the blame at the feet of Dr. Gachet. He wrote “And yet more than ever I believe it was because Dr. Gachet of Auvers-sur-Oise, because of him, I say, that van Gogh on that day, the day he committed suicide in Auvers-sur-Oise, departed this life”. Some dismissed the words of Artaud as the writings of a madman, as he had spent more than half his life in an asylum. However, some took the alternative view that Artaud may have had special insights into the relationship between Gachet and van Gogh for exactly that very same reason.

Dr. Paul Gachet passed away in 1909. His son and namesake (Paul Gachet Jr.) was a recluse who spent the majority of his life promoting his father’s legacy and the van Gogh legend. During World War II, he was able to hide the Gachet art collection in a cave located behind the family home. 24 Despite numerous visits from the German Nazi occupation force, the location of the priceless art collection was never discovered. Paul Gachet Jr vigorously defended his father’s reputation and pushed back on any accusations including those of Artaud. Perhaps in an effort to reverse a wave of changing sentiment, between 1949 and 1954 he donated to the French government the majority of the vast collection of art that his father had accumulated. This also exposed the pieces to public and professional scrutiny, and it was subsequently discovered that many of them were frauds.

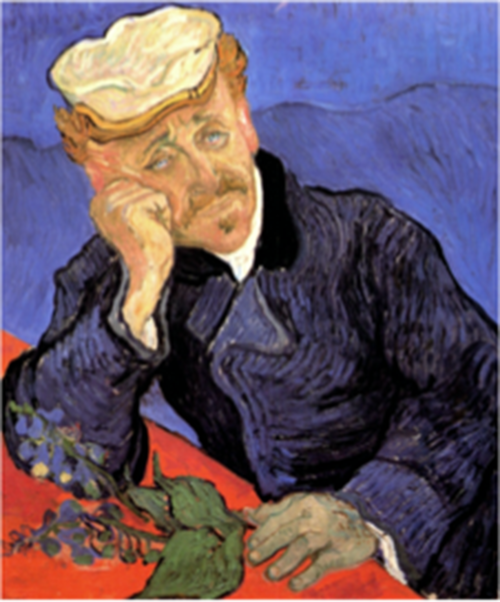

There is a second version of the Dr. Gachet portrait which was owned by the Gachet family until it was donated in the 1950s (Fig 16). This version is a much simpler rendition, lacking many of the details of the original one. Perhaps the one unifying theme is the presence of the doctor who is, in this version, holding the sprig of foxglove. Over the second half of the 20th century, the second version came under increasing scrutiny and thus considerable controversy. While some vehemently declared it an authentic van Gogh, others suspected that it was more likely a copy by a lesser artist, perhaps by Dr. Gachet or his son Paul Gachet Jr. As a consequence, in 1999 the Musée d’Orsay had the painting evaluated using infrared, ultraviolet, and chemical analysis. The results demonstrated unequivocally that the second version was a fraud, executed by someone other than van Gogh. Reference Henley25 There were many other paintings from the Gachet collection that have subsequently proven to be copies of other paintings. However, the carefully appended signatures mean that they were not innocent copies, but deliberate forgeries. Even the etching of Dr. Gachet that has historically been attributed as the only van Gogh etching has been questioned as to its authenticity. These revelations have significantly undermined the credibility of both father and son, and in the end, Paul Gachet Jr has been reframed as an unscrupulous person.

Figure 16. Second version of Portrait of Doctor Gachet (Date unknown, Artist unknown, oil on canvas, 67 × 56 cm, Musee d’Orsay, Paris). This second version is thought to have been copied from the original van Gogh painting somewhat later, possibly by Dr. Gachet, Paul Gachet Jr., or someone else.

In another conspiracy related to the Gachet family, Reference Fells26 some have postulated that there was a love affair between van Gogh (then 37) and Marguerite Gachet (age 21). Van Gogh visited the Gachet home on numerous occasions, and did two paintings of Marguerite ( Marguerite Gachet in the Garden (Fig 17) and Marguerite Gachet at the Piano). There are several versions of this conspiracy theory. The one most commonly cited is that the two were attracted to one another, and perhaps were even contemplating an engagement, but that Dr. Gachet stepped in and forbid the two from seeing one another. According this story line, the dispute with the doctor and the disappointment of love denied lead to his suicide.

Figure 17. Marguerite Gachet in the Garden (1890, oil on canvas, 46 × 55.5 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris). This is one of two paintings of Marguerite Gachet done by van Gogh in the summer of 1890.

Yet another conspiracy theory is that van Gogh did not even commit suicide, and that his gunshot wound was inflicted by a group of boys. 27 This story line emerged in 1957 when an elderly man named René Secretan gave an interview indicating that he was one of a group of hoodlums who accidentally or on purpose shot van Gogh. Reference Naifeh and Smith28 This version of events was depicted in the 2018 movie At Eternity’s Gate. Unfortunately, there is no corroborating evidence to support this theory, including the contemporaneous letters and documents. In fact, the contemporaneous accounts would support the version that van Gogh shot himself, as he admits to doing so afterwards. This is another example of the lore that has evolved over the 130 years since his death.

Finally, the history of the painting Portrait of Dr. Gachet must also be listed as somewhat of a mystery, if not conspiracy. The original van Gogh version was given to Dr. Gachet as a gift. The painting was sold to Paul Cassirer in 1904, Kessler in 1904, and Druet in 1910. The following year, it was sold to the Städtische Galerie in Frankfurt, Germany where it was displayed for 23 years. From 1933 to 1937, the painting was removed from exhibition, and in 1937 was confiscated by the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda as part of the Nazi Germany campaign to rid itself of degenerate art. Hermann Goering (through his agent Sepp Angerer) sold it to Franz Koenigs in Paris, who transported the painting to Knoedler’s gallery (which itself would come under scrutiny for art fraud in the 21st century) in New York. The painting came under the custody of Siegfried Kramarsky, who lent the piece to the Metropolitan Museum of Art on a frequent basis.

The painting went up for auction at Christie’s New York on 15, May, 1990 (a century less 3 weeks from the date of painting). The piece sold for 82.5 million dollars (a record at the time) to a Japanese businessman, and the painting has never been seen in public since. It was rumoured that he threatened to have the painting buried with him (he died in 1996), while other rumours suggest that it was sold to an Austrian-born investment fund manager. Thus, even the painting of Dr. Gachet has had its own set of intrigues.

Conclusions

When van Gogh learned in the spring of 1890 that his paintings exhibited at the Les XX in Brussels (January 1890) been highly acclaimed, he was unable to stand this success. He attributed his 2-month breakdown to read the positive reviews. He wrote “As soon as I heard that my work was having some success, and read the article in question, I feared at once that I should be punished for it; this is how things nearly always go in a painter’s life: success is about the worst thing that can happen”. Reference Jansen, Luijten and Bakker4 (Letter 864, 29 April, 1890) His words were written from the confines of the asylum and are both insightful and contain humour as well. Van Gogh became the poster child for the premise that the depths of despair were what allowed the artist to achieve their highest degree of creativity.

Vincent van Gogh’s career as a painter lasted just 10 years (1880–1890). Arguably, his contributions during the “Dutch years” (1880–1886) would have hardly distinguished himself as an artist. His move to Paris (1886–1887) allowed him to consort with other well-known avant-garde artists. The quality of his paintings improves substantially during this time period, but still would not have been particularly distinguishing. However, when van Gogh moved to the south of France in February 1888, his paintings were transformed. In just 30 months, van Gogh painted essentially every painting for which he would become world-renowned. Clearly, a portion of this transformation is the maturation of van Gogh as an artist. Another factor in this transformation is the brilliant light of Provence, for which van Gogh had an intense affinity (Gauguin was right, after all). Finally, one is left to conjecture about the influence of the many drugs, herbs, and medications that may have had an influence on his vision, on his perceptions, and on his state of mind. The lack of specific information regarding these various treatments means that, unless new information is unearthed, the role of these substances will remain unanswerable.

As for Dr. Gachet, there are as many views of him as there are conspiracy theories. Was he a sympathetic patron who tried to help van Gogh to the best of his abilities? Or was he a charlatan and a murderer? This too may be an unanswerable question, unless we ask “Was it Dr. Gachet, in the kitchen, with the foxglove?”

Acknowledgements

None.