The bundles and fascicles of the specialised ventricular Purkinje conduction system are insulated from the adjacent contractile cardiomyocytes by fibrous sheaths, which prevent direct myocardial activation.Reference Rosenbaum, Elizari and Lazzari 1 It is the widely distributed connections with subendocardial cardiomyocytes that initiate ventricular myocardial depolarisation. The postero-inferior displacement of the atrioventricular node in patients with atrioventricular septal defect is therefore not the likely cause of the commonly occurring abnormalities in the initiation and subsequent propagation of ventricular depolarisation.

In the normal heart, it is the infero-septal and supero-lateral papillary muscles of the mitral valve that are among the first left ventricular structures to be depolarised.Reference Durrer, van Dam, Freud, Janse, Meijler and Arzbaecher 2 This requires that the “edges of the fan” of left bundle fascicles be directed towards the origins of these papillary muscles as they emerge from the trabeculated left ventricular endocardial surface.Reference Rosenbaum, Elizari and Lazzari 1 Anatomic variation in the positions of these papillary muscles, as seen in hearts with common as opposed to separate atrioventricular junctions, might therefore cause variation in the spread of left ventricular myocardial activation, which would be manifested by a deviation of the QRS axis on the electrocardiogram when compared with normal findings. Such a deviation in the location of the papillary muscles is known to be a feature of patients with atrioventricular septal defect in the setting of a common atrioventricular junction.Reference Anderson, Ho, Falcao, Daliento and Rigby 3 – Reference Sulafa, Tamimi, Najm and Godman 5 This cohort, therefore, provides a unique model for studying electrophysiologic–anatomic relationships in the heart. This has been prominently considered as in the so-called “ostium primum” defect, in which shunting across the septal defect occurs only at the atrial level, left ventricular activation is known to be typically directed leftward and superiorly compared with normal, with a mean frontal plane QRS axis between −60 and −130°.Reference Ebels and Anderson 6

In a previous study of patients with the primum defect, we showed that the ratio of distances of the superior and inferior papillary muscles from the mid-septum was significantly lower than that in normal subjects. That study also documented a significant correlation between the locations of the papillary muscles and the degree of leftward deviation of the QRS axis.Reference Hakacova, Wagner and Idriss 4 In our current study, we have also included patients having the so-called “complete” variant of atrioventricular septal defect, the significant feature of this group being that shunting across the defect occurs at both atrial and ventricular levels, such shunting being exclusively at atrial level in those with the primum defect. We hypothesised, therefore, that the QRS axis would differ between the two types of atrioventricular septal defect, as shunting at only the atrial level causes only a volume, and hence diastolic, overload for the right ventricle, whereas shunting at the ventricular level would cause both volume and pressure, or systolic, right ventricular overloads.

It was shown previously that isolated right ventricular pressure overload, due to pulmonary hypertension, alters the balance of QRS forces and causes right axis deviation.Reference Blyth, Kinsella and Hakacova 7 With only the right ventricular volume overload produced by the so-called “ostium secundum” atrial septal defect, however, there is well-documented absence of right axis deviation.Reference Butler, Leggett, Howe, Freye, Hindman and Wagner 8 , Reference Siddiqui, Samad and Hakacova 9 Only the patients with defects permitting ventricular shunting, therefore, would be expected to have the increase in right ventricular wall tension that would affect its ventricular gradient sufficiently to alter both its depolarisation and repolarisation. The resultant late rightward QRS forces could be expected to “overbalance” the late leftward QRS forces caused by the abnormally positioned papillary muscles supporting the left atrioventricular valve.Reference Kamphuis, Haeck and Wagner 10 In this study, therefore, we have compared the ratios of the distances of the left ventricular papillary muscles from the mid-septum in patients with “primum” defects with those of patients with atrioventricular septal defects permitting both atrial and ventricular shunting.

Methods

Definitions

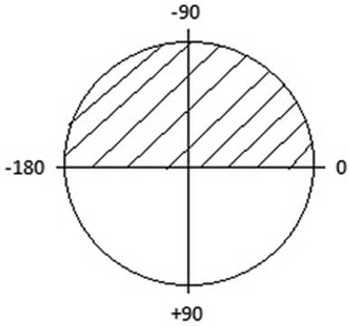

“Atrioventricular septal defect” is an anatomic defect characterised by a common atrioventricular junction in which, depending on the attachments of the bridging leaflets of the common atrioventricular valve, shunting through the septal defect is confined at the atrial level, the ventricular level, or occurs at both levels.Reference Anderson, Ho, Falcao, Daliento and Rigby 3 The “QRS axis” is defined as the mean vector of the QRS complex in the frontal plane. The superior QRS axis in the frontal plane is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The frontal plane of the QRS axis is shown, with the superior QRS axis depicted by stripes.

Population studied

We have studied all patients with atrioventricular septal defect having both atrial and ventricular shunting admitted to the Children’s Heart Centre in Lund between the years of 2008 and 2013 who received specialised echocardiographic interrogation as described below and who met our criteria for inclusion in the study. These were as follows:

-

∙ Access to the findings of a 12-lead surface electrocardiogram and cross-sectional echocardiogram performed preoperatively. The electrocardiogram was recorded on the same day or within 1 week of the echocardiogram.

-

∙ Superior QRS axis on the frontal plane.

-

∙ Age above 1 month.

-

∙ Echocardiographic evidence of a common atrioventricular junction, with shunting through the atrioventricular septal defect at both the atrial and ventricular levels.

-

∙ Surgical confirmation of the presence of common atrioventricular junction with left–right communication at both atrial and ventricular levels.

Data concerning QRS axis and position of papillary muscles in patients with atrioventricular septal defect permitting only atrial shunting, and of normal subjects, were extracted from the population assessed in our previous study.Reference Hakacova, Wagner and Idriss 4 The patients with primum defects had been diagnosed and followed up at the Duke University Medical Center from 1996 until 2007. Echocardiographic images were reviewed independently by an investigator and an echo expert to confirm the presence of the shunting through the atrioventricular septal defect at the atrial level only.

Echocardiographic measurements

Echocardiographic measurements of the patients with atrial and ventricular shunting were recorded by one observer (N.H.) blinded to the electrocardiographic data. The presence of a common atrioventricular junction, specifically the trifoliate structure of the left atrioventricular valve, was used to confirm the diagnosis of the atrioventricular septal defect.Reference Anderson, Ho, Falcao, Daliento and Rigby 3

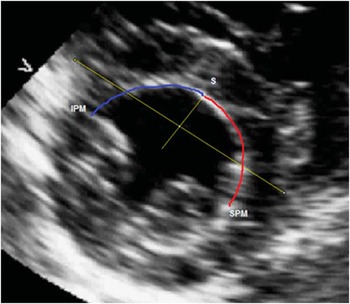

Ultrasound images were used to define the position of the papillary muscles within the left ventricle. Images were analysed offline using the Xcelera program (Philips Medical, Andover, Massachusetts, United States of America). The method of assessing the positions of papillary muscles was previously published.Reference Hakacova, Robinson, Maynard, Wagner and Idriss 11 The position of each muscle was calculated from the subcostal short axis views at the level of their origin from the left ventricular wall. Using an image analysis freeware program (Image J; Bethesda, Maryland, United States of America), we then measured the distances of the points of insertion of both muscles from the midline of the septum and calculated the ratio between these distances (Fig 2).

Figure 2 The distance of the superior papillary muscle (SPM) from the mid-septum S is highlighted in red, whereas the distance of the inferior papillary muscles (IPM) from the mid-septum S is highlighted in blue.

Electrocardiographic measurements

The axis of the QRS complex was directly recorded from the software measurements (Philips Tracemaster Vue, Philips Healthcare, Netherlands). The QRS axis was determined by using the areas subtended by each waveform of the QRS complex in all of the limb leads and the augmented leads.Reference Butler, Leggett, Howe, Freye, Hindman and Wagner 8 An independent observer (G.W.) confirmed the general accuracy of the automated QRS axis measurements by visually estimating the QRS axis using the amplitudes of the waveforms of the QRS complex.Reference Siddiqui, Samad and Hakacova 9

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to determine the association between the position of insertions of the papillary muscles and the QRS axis. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the locations of the papillary muscles and QRS axis between the two groups of patients with atrioventricular septal defect. Linear regression was used to adjust for age when examining the association between diagnosis and continuous QRS. SPSS version 19.0 was used to perform the linear regression analysis. All other data analyses were performed using the JMP test (JMP 10.1.0 for Windows), version 11. A two-tailed value for p<0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. The variables were presented as mean values±1 SD.

Results

We included 18 patients with atrial and ventricular shunting and 23 with exclusively atrial shunting. Their baseline demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Those with ventricular shunting had a mean age of 3.1±2.6 months and weighed 5±1.4 kg. Of the cohort, 10 (55%) had Down’s syndrome. Those with exclusively atrial shunting were older, with a mean age of 111±91 months.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the populations studied.

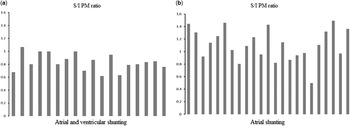

In Figure 3, we show the distributions of the papillary muscle positions in the two groups. The ratios of the distances between the papillary muscles and the mid-septum in those with ventricular shunting extended from 0.67 to 1.06%, with a median of 0.91%. In those with exclusively atrial shunting, the comparable values extended from 0.49 to 1.49%, with a median of 1.1%. There was no significant difference, therefore, in the locations of the papillary muscles between the two groups of patients with atrioventricular septal defect.

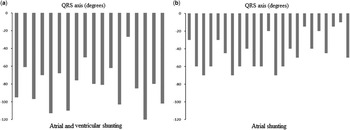

Figure 3 The histogram shows the location of the papillary muscles (PM) in those with atrial and ventricular shunting ( a ) as opposed to those with exclusively atrial shunting ( b ). S/I PM ratio=superior/inferior PM ratio.

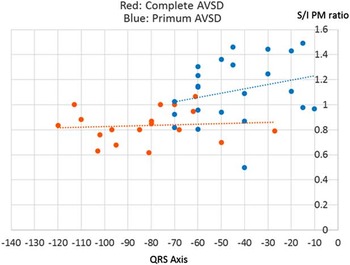

In Figure 4, we show the distributions of the QRS axis in the two groups. The group with ventricular, in addition to atrial, shunting had eight patients with rightward QRS axis direction, but no patients with this pattern were found among the patients with exclusively atrial shunting. The QRS axis in the frontal plane of those with atrial and ventricular shunting extended from −27 to −120°, with a median of −80°. The comparable axis of the patients with exclusively atrial shunting extended from −15 to −70°, with a median of −45°. The association between diagnosis and the position of the QRS axis was highly statistically significant (p<0.0001). This association, furthermore, did not change significantly when adjusting for age using linear logistic regression, remaining highly statistically significant (p=0.001). In Figure 5, we show the relationships between the ratio of distances of the papillary muscles from the septum and the amount of leftward deviation in the frontal plane QRS axis. The correlation coefficient between this ratio and the QRS axis was very low in those with atrial and ventricular shunting, specifically 0.1 (p=0.4). In those with exclusively atrial shunting, in contrast, the correlation coefficient was much better, at 0.26 (p=0.01).

Figure 4 The histograms show the QRS axis deviation in those with atrial and ventricular shunting ( a ) and those with exclusively atrial shunting ( b ).

Figure 5 The relationships between the ratio of the distances between the superior (S) and inferior (I) papillary muscles (PM) from the septum, and the amount of leftward deviation of the frontal plane QRS axis are shown in red for the patients with atrial and ventricular shunting, and in blue for those with exclusively atrial shunting. AVSD=atrioventricular septal defect.

Discussion

Our investigation shows that there is no association between the location of the left ventricular papillary muscles within the short axis of the ventricular cone and the arrangement of the QRS axis in patients with atrioventricular septal defect permitting both atrial and ventricular shunting. In contrast, in those patients with the so-called “primum” defect, in whom shunting is confined exclusively at the atrial level, there is a significant association between the locations of the papillary muscles and the degree of the QRS axis. On this basis, we suggest that there are other factors beyond the simple location of the papillary muscles that influence the QRS axis in patients with an atrioventricular septal defect and common atrioventricular junction in whom shunting occurs at both atrial and ventricular levels. The histogram of the distribution of the QRS axis in those patients with ventricular shunting shows that several have superior and rightward deviation of the QRS axis. We suggest that these patients have pressure-overloaded right ventricles in consequence of the increased right ventricular pressure resulting from the left-to-right ventricular shunting. These patients, however, are much younger than those with exclusively atrial shunting. It could be that some of the patients with additional ventricular shunting may have increased pulmonary resistance as a result of their age, this providing an alternative explanation for the predominance of the rightward QRS forces in the frontal plane. In this regard, it has previously been shown that right ventricular pressure overload influences the QRS forces so as to cause right axis deviation.Reference Blyth, Kinsella and Hakacova 7 In patients with ventricular shunting, therefore, the additional left-to-right flow would be expected to increase the tension in the walls of the right ventricle, thus influencing the gradient in the right ventricular myocardium sufficiently to alter both its depolarisation and repolarisation. It may be, therefore, that the resultant late rightward QRS forces are able to counteract the late leftward QRS forces seen as a consequence of the malpositioned papillary muscles.Reference Kamphuis, Haeck and Wagner 10 Studying separate QRS sequences, for example, by three-dimensional vectrocardiography may bring additional information regarding the correlation of direction of late as opposed to early forces with the location of the papillary muscles.

Our study is limited in that we currently included only patients known to have superior axis deviation, and studied only the location of the papillary muscles as influencing the degree of deviation of the superior QRS axis. This, however, was an integral component of our criteria for inclusion, as our purpose was to analyse the “pure” effect of the location of the papillary muscles on the degree of superior deviation of the QRS axis. We conclude, therefore, that in contrast to patients with an atrioventricular septal defect permitting shunting only at the atrial level, in whom the positions of the papillary muscle positions correlate with the degree of QRS axis, there are no such relationships between these anatomic and electrophysiologic variables in patients with atrioventricular septal defect permitting both atrial and ventricular shunting. It is the presence of the ventricular shunting, and/or their younger age, that causes pressure overload to cancel the leftward QRS forces caused by the abnormally positioned papillary muscles. Our investigation has expanded the understanding of the underlying factors behind the deviation of the QRS axis in patients with atrioventricular septal defect and common atrioventricular junction. We submit that this knowledge will be important when seeking to differentiate between the physiological and pathological changes that influence the depolarisation of the heart.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

This study complies with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and was approved by the ethics committee.