The November 2020 issue of Cardiology in the Young contains the inaugural five manuscripts from the Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Outcome Collaborative Reference Sood, Jacobs and Marino1–Reference Ilardi, Sanz and Cassidy5 , marking the beginning of the partnership between the Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Outcome Collaborative and Cardiology in the Young. In this issue of Cardiology in the Young, this article is part of the first set of three papers from the Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Outcome Collaborative R13 Grant funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health of the United States of America, which defines the research agenda for the next decade across seven domains of cardiac neurodevelopmental and psychosocial outcomes research. Reference Sood, Jacobs and Marino6–Reference Sood, Lisanti and Woolf-King8

The ultimate goal of research within the CHD population is to improve outcomes for patients and families. How we measure, describe, and interpret neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes can completely alter the effectiveness of research and clinical efforts to improve and optimise outcomes. Thus, future investigations need to expand our current understanding and characterisation of neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes in children with CHD. While considerable effort has gone into identifying a characteristic “neurodevelopmental signature” of children with CHD, a more nuanced characterisation is critical to guiding work on mechanisms for modifiable change, as well as timely identification, prevention, and intervention strategies.

Research has given us a general sense of relative weaknesses and commonly provided diagnoses (from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Edition) from a cross-sectional perspective. Reference Cassidy, Ilardi and Bowen9 A single, characteristic outcome for children with CHD is unlikely given the heterogeneity in risk factors, mechanisms of action, comorbidities, and how neurodevelopmental concerns change over the course of development. In addition, little is known about the impact of cultural, linguistic, geographic, and socio-economic factors on outcomes. While we have identified some key risk factors, additional research is needed to determine which are modifiable and promote resilience.

We must move beyond mere descriptive data to understand the longitudinal trajectory of outcomes, how these present over the course of development, and the functional impact of neurodevelopmental differences. Along with understanding risk factors, we also need to understand those factors that promote resilience and positive outcomes. In collaboration with diverse patients, families, schools, and other stakeholders, this knowledge will support the critical process of prioritising concerns, developing targeted treatment and intervention strategies, improving access to resources, and reducing the burden of long-term care.

The Neurodevelopmental and Psychological Outcomes Working Group of the Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Outcome Collaborative is composed of multidisciplinary topic area experts (in psychology, neuropsychology, cardiology, developmental paediatrics, nursing) from the USA, Canada, and New Zealand, a health disparities expert (W. Nembhard) and a parent stakeholder (A. Basken) (Table 1). The Working Group was formed in 2018 with the goals of identifying (1) significant knowledge gaps related to characterisation of neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes in CHD; (2) critical questions that must be answered to further knowledge, policy, care, and outcomes; and (3) investigations needed to answer these critical questions. The effort was supported by a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute R13 grant awarded to the Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Outcome Collaborative in collaboration with the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, which funded a two-day meeting of multidisciplinary, multinational experts, and patient/caregiver stakeholders in Kansas City, MO. This paper presents the top five critical questions identified by the Working Group (Table 2) and provides specific recommendations for science and health policy to inform future research on the characterisation of neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes in CHD.

Table 1. Neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes working group participants

WG = Working Group. *Working Group Co-Lead **Health Disparities Expert.

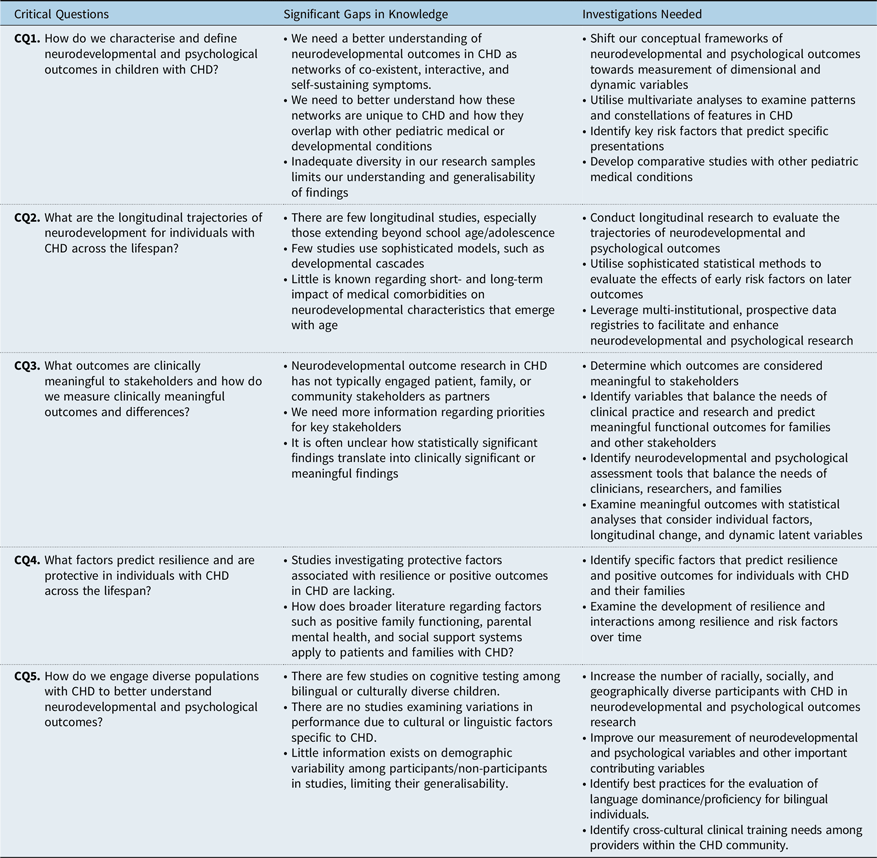

Table 2. Neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes: critical questions, significant gaps in knowledge, and investigations needed

CQ = critical question.

Critical question 1: How do we characterise and define neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes in children with CHD?

Existing knowledge

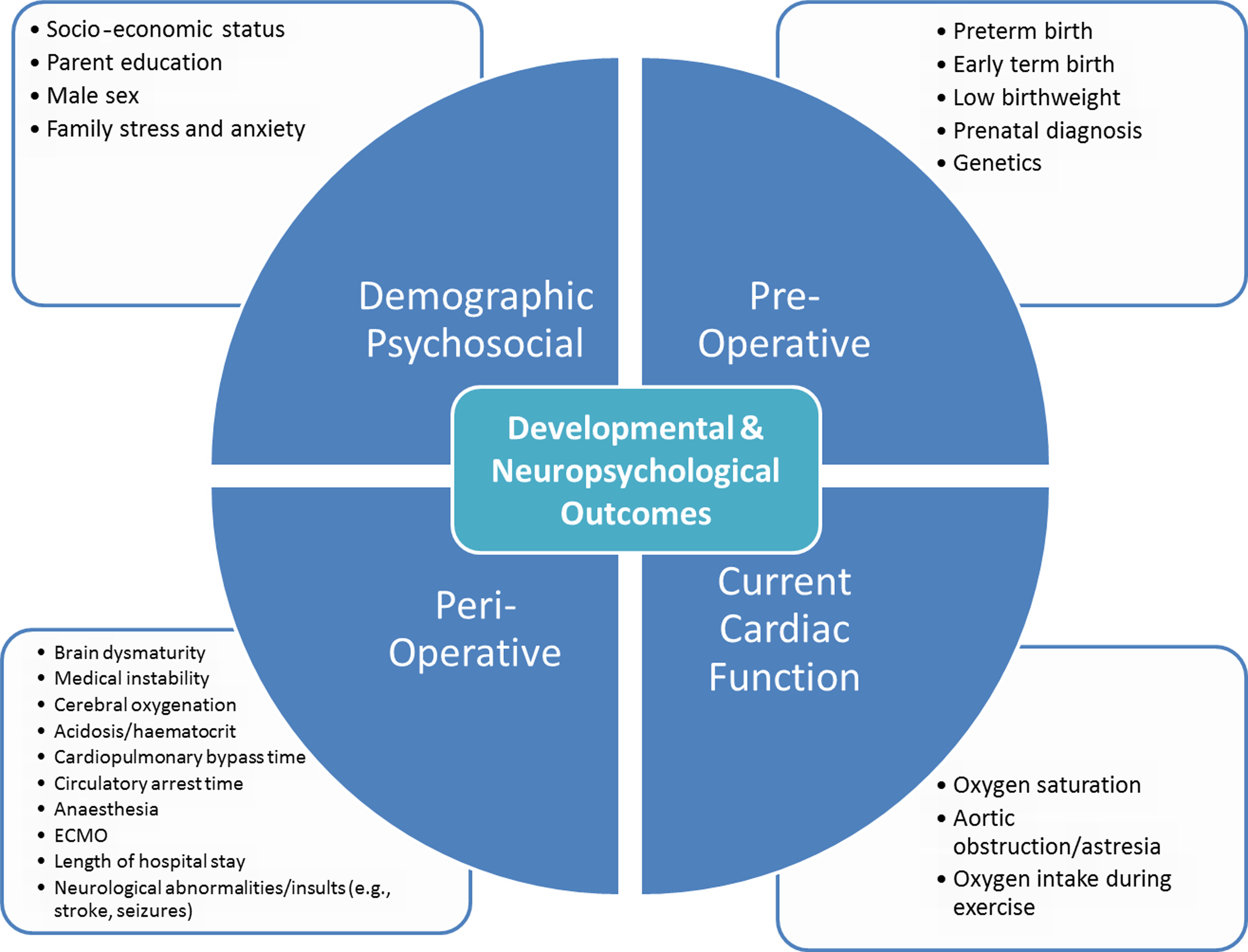

Research has demonstrated lower performance in specific neurodevelopmental and psychological skill areas, including attention and executive skills, processing speed, language, visual-spatial and motor skills, memory, reading and math, and adaptive functioning, as well as increased prevalence of emotional and behavioural symptoms in children with CHD. Reference Bellinger and Newburger10–Reference Muñoz-López, Hoskote and Chadwick23 This contributes to increased use of special education and therapeutic services. Reference Mulkey, Bai and Luo24,Reference Oster, Watkins and Hill25 Although these findings are often referred to as the “neurodevelopmental signature” of CHD, there is no evidence for a single phenotype, or profile, for children with CHD. Instead, there is significant variability within and across domains of functioning, including age-typical performance for some children. Those children with genetic disorders or syndromes may have more global impairment or specific findings related to those syndromes. Reference Carey, Liang and Edwards26–Reference Latal29 With respect to psychological diagnoses with clearly defined constellations of symptoms, there are increased rates of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorder, and Anxiety Disorders, although these rates also vary based on severity of the CHD and other comorbidities. Reference Kovacs, Saidi and Kuhl30–Reference Jaworski, Flynn and Burnham34 In addition, there are multiple risk factors for neurodevelopmental and psychological problems, including cardiac (e.g., pre- and peri-operative, current cardiac function) and non-cardiac (e.g., psychosocial and demographic) factors that may substantially influence long-term outcome (see Figure 1, from Cassidy et al. Reference Cassidy, Ilardi and Bowen9 ).

Figure 1. Known factors that affect variability in developmental and neuropsychological outcomes for children and adolescents with CHD. ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Reproduced with permission from Cassidy et al. (2018), Congenital Heart Disease: A Primer for the Pediatric Neuropsychologist, Child Neuropsychology, 24 (7) (Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com).

Significant gaps in knowledge

Despite rapid advancements in knowledge, heterogeneous findings and unexplained variance are problematic for guiding early detection and targeted interventions. Conceptually, existing research either uses a categorical approach with respect to diagnostic data (e.g., does a child meet diagnostic criteria for a disorder) or uses symptoms in isolation on a dimensional scale (e.g., identifying weaknesses in attention, executive function, and motor skills). Reference Cassidy, Ilardi and Bowen9 These approaches are less helpful in understanding neurodevelopmental profiles that fall outside of strict diagnostic categories from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Edition, where symptoms overlap across multiple diagnoses, or how these symptoms evolve over the course of development. There has been a more recent push towards thinking of neurodevelopmental or psychological disorders as networks of co-existent, interactive, and self-sustaining symptoms, rather than as categorical entities. Reference Cramer, Waldorp and van der Maas35,Reference Borsboom and Cramer36 This approach would likely provide more flexibility in understanding the range of possible outcomes in children with CHD. It is also unclear how networks of observable neurodevelopmental and psychological problems are unique to CHD, or how they may be similar to other paediatric high-risk medical or developmental conditions.

Finally, there are substantial limitations to our existing knowledge about outcomes given inadequate diversity in our research samples (see Critical Question #5 below). Participants are primarily white, urban, and have higher socio-economic status. This limits our ability to generalise findings to diverse, international populations with CHD, as well as to use neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes to understand issues and obstacles in accessing care.

Investigations needed

-

(1) Shift our conceptual frameworks of neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes towards measurement of dimensional and dynamic variables

In 2009, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) proposed the Research Domain Criteria Project (http://www.nimh.nih.gov/research-priorities/rdoc/index.shtml) as a framework for examining psychopathology in terms of measurable, dimensional behavioural and cognitive constructs that cut across diagnostic categories, that include normal variation, Reference Cuthbert37,Reference Insel, Cuthbert and Garvey38 and that account for evolution and change across development. Reference Casey, Oliveri and Insel39 This approach intends to move psychological outcomes research towards the era of precision medicine and conceptually allows us to better integrate genetics and neurosciences in explanations of clinical phenomena.

-

(2) Utilise multivariate analyses to examine patterns and constellations of features in CHD

The Research Domain Criteria Project approach lends itself to sophisticated, multivariate statistical modelling that examines patterns in data (graph theory, Bayesian modelling, principle component analysis) that could identify those constellations of features that are most prevalent in children with CHD. While an understanding of categorical diagnoses remains important, as it allows us to work within clinical and educational systems, this allows us to move towards conceptualising outcomes as networks of interrelated cognitive and behavioural features and better capture the range and heterogeneity of outcomes in CHD.

-

(3) Identify key risk factors that predict specific phenotypic presentations

Current studies tend to divide patients into discrete cardiac diagnostic categories; however, these are heterogeneous groups. Shifting our conceptual framework towards the Research Domain Criteria Project model might encourage us to examine shared features across cardiac diagnoses that impact brain development (e.g., aortic arch obstruction, single ventricle status, degree of shunting) along with perioperative or patient-specific factors that also contribute (e.g., use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, haemodynamic factors, pre-term birth, socio-economic status). If we are able to move towards identifying specific mechanisms of action, then we may identify potentially modifiable risk factors for specific problems and provide more targeted interventions.

-

(4) Develop comparative studies with other paediatric medical conditions

Comparative studies of neurodevelopment with other medical populations that impact early brain development, such as prematurity, genetic disorders, epilepsy, or perinatal stroke, will allow us to further explore mechanisms, or root causes of neurodevelopmental and psychological differences. These studies can help differentiate those mechanisms of action that are shared across medical populations from those that may be specific to children with CHD.

Critical question 2: What are the longitudinal trajectories of neurodevelopment for individuals with CHD across the lifespan?

Existing knowledge

The majority of knowledge related to the neurodevelopment of individuals with CHD has been gained from cross-sectional studies in infants, toddlers, school age, and adolescent children, Reference Karsdorp, Everaerd and Kindt40–Reference Wilson, Smith-Parrish and Marino43 with a limited number of single-cohort longitudinal studies. Reference Bellinger, Jonas and Rappaport44–Reference Brosig, Bear and Allen46 Through these longitudinal studies, it is apparent that neurodevelopment is somewhat discontinuous. That is, early neurodevelopment has limited predictive value into the school-age years and beyond. Reference McGrath, Wypij and Rappaport17,Reference Goldberg, Lu and Sleeper47 For example, many children with CHD who present as typically developing at age two showed deficits by age four. Reference Brosig, Bear and Allen46 Further, longitudinal neuropsychological data suggest increasing prevalence of neurodevelopmental problems over time, as well as different areas of concern over time. For example, problems with language, speech, motor, and visual-motor development are commonly reported in early life, whereas concerns related to executive function, social cognition, academic achievement, and anxiety/depression are more apparent during school age, adolescence, and young adulthood. Reference Mills, McCusker and Tennyson19,Reference Kovacs, Saidi and Kuhl30,Reference Wilson, Smith-Parrish and Marino43,Reference Bellinger, Wypij and Kuban48–Reference Klouda, Franklin and Saraf51

Research with preterm infants, a group that has been compared to CHD, has demonstrated how critical longitudinal research is to understanding neurodevelopmental and psychological profiles. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network, which includes longitudinal follow-up of neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants, recognises that deficiencies may not manifest until later childhood and can only be understood in the context of a child’s overall developmental trajectory. Reference Das, Tyson and Pedroza52 In addition, epidemiologic studies from countries with population databases have identified links between prematurity and neurocognitive impairment in late adulthood, Reference Heinonen, Eriksson and Lahti53,Reference Vohr54 which are increasingly recognised in the CHD population Reference Ilardi, Ono and McCartney15 , again providing evidence for the importance of longitudinal assessment of high-risk neonates.

An understanding of developmental cascades is also critical to longitudinal research. Developmental cascades refer to the cumulative effect of the many interactions, both direct and indirect, occurring between a range of risk factors (i.e., biological, neurodevelopmental, psychosocial, socioeconomic, and cultural) on later development or outcomes. Reference Cox, Mills-Koonce and Propper55,Reference Masten and Cicchetti56 Developmental cascade models enable better identification of independent or interdependent contributions of each risk factor, including early risk factors that are relatively stable over time (e.g., genetics). In turn, these early factors impact later outcomes in a specific domain through mediating and moderating effects, as well those early factors that can be modified or whose effect seems to dissipate over time. Reference Cox, Mills-Koonce and Propper55–Reference Bornstein, Hahn and Wolke57 While developmental cascade models have been applied in research to understand normal development Reference Wade, Browne and Plamondon58 and development in the preterm population, Reference Rose, Feldman and Jankowski59,Reference Rose, Feldman and Jankowski60 the use of developmental cascades to uncover the cumulative risk over time within the CHD population is just emerging. Reference Cassidy, White and DeMaso61

Significant gaps in knowledge

There has been only limited research that considers how neurodevelopmental and psychological domains evolve and impact one another over time in the CHD population, and as a result, the potential to target these factors and modify their course has not been studied. Reference Cassidy, White and DeMaso61 Few longitudinal studies exist in CHD, and studies beyond school age and adolescence are lacking. As adolescents with CHD transition to adulthood, loss to follow-up is common, limiting opportunities for long-term analysis of outcomes. Reference Gurvitz, Valente and Broberg62 Application of more sophisticated models, such as developmental cascades, is only in its early stages. In addition, little is known about the short- and long-term impact of medical comorbidities (e.g., cardiac status, neurological events, genetic variants) on neurodevelopmental and psychological characteristics that emerge with age. These critical gaps in knowledge around the longitudinal course of development in CHD limit our ability to more comprehensively characterise neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes.

Investigations needed

-

(1) Conduct longitudinal research to evaluate the trajectories of neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes

Longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate neurodevelopmental and psychological trajectories from infancy through adulthood across the spectrum of CHD. These will serve to identify the short- and long-term impact of medical and patient-specific factors on later outcomes. Studies should examine the interaction between neurodevelopmental and psychological characteristics over time and how these interactions may influence later outcomes via developmental cascades. This would also help inform the predictive value of specific standardised measures over time.

-

(2) Utilise sophisticated statistical methods to evaluate the effects of early risk factors on later outcomes

At a more granular level, longitudinal statistical methods such as structural equation modelling would enable investigators to consider both direct and indirect effects of earlier risk factors on later outcomes. This analytic approach has been successfully performed in several studies in both typically developing children and high-risk populations. Reference Rose, Feldman and Jankowski60,Reference Cassidy, White and DeMaso61,Reference Masten, Roisman and Long63,Reference O’Shea, Allred and Dommann64

-

(3) Leverage multi-institutional, prospective data registries to facilitate and enhance neurodevelopmental and psychological research.

While studies in smaller samples will continue to be helpful in providing further depth of knowledge around specific topic areas, large-scale collaborative data registries are more adequately powered for statistical techniques that model interactive networks of symptoms over time in longitudinal samples and more accurately represent the larger and more diverse population of children with CHD. Indeed, prospective, longitudinal studies that follow populations from birth through adolescence have been successfully implemented in other medical populations, such as premature birth. Reference O’Shea, Allred and Dommann64–Reference Larroque, Breart and Kaminski66 Multi-institutional, prospective data registries would facilitate collection of longitudinal neurodevelopmental and psychological data in CHD by using data already obtained through clinical practice, thereby increasing feasibility and reducing the costs.

Critical question 3: What outcomes are clinically meaningful to stakeholders and how do we measure clinically meaningful outcomes and differences?

Existing knowledge

Thus far, the majority of neurodevelopmental and psychological outcome research in CHD has been driven by academic researchers and clinician stakeholders working in specialty care settings. The focus has been to describe a broad spectrum of developmental, neuropsychological, and psychological outcomes. Reference Sood, Jacobs and Marino1 Assessment tools are variable, including screening instruments and large batteries of tests and rating scales, with analyses focusing on broad index scores and dimensional outcome variables. Analyses commonly evaluate statistically significant differences in neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes by comparing children with CHD to a normative sample or control group (including siblings), and/or by comparing groups with different types of CHD. Reference Bellinger, Wypij and duPlessis11–Reference Ilardi, Ono and McCartney15,Reference Miatton, De Wolf and François18,Reference Sanz, Berl and Armour20,Reference Wernovsky, Stiles and Gauvreau21,Reference Bellinger and Newburger10 There are, however, emerging studies that have started to explore the association of these findings with functional outcomes, such as academic functioning or quality of life. Reference Cassidy, White and DeMaso61,Reference Sanz, Wang and Berl67,Reference Gerstle, Beebe and Drotar68

Significant gaps in knowledge

Despite increasing emphasis on community-engaged research in other fields, Reference Hollin, Donaldson and Roman69–71 neurodevelopmental and psychological outcome research in CHD has not typically engaged patient, family, or community stakeholders as partners or advisors and has not directly evaluated which neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes are considered meaningful to different stakeholder groups. As a result, we remain generally unaware of primary neurodevelopmental concerns and priorities across the lifespan for patients with CHD, their parents, teachers, and other stakeholders. In addition, statistically significant findings for a given outcome variable in samples with CHD may not translate into clinically significant or meaningful results, including those that might influence clinical practice, academic functioning, or quality of life.

Investigations needed

-

(1) Determine which outcomes are considered meaningful to stakeholders

Qualitative and mixed-methods research can be used to explore which outcomes are clinically meaningful to patients, families, teachers, Reference Olson, Seidler and Goodman72 medical providers, and other stakeholders. Reference Alderfer and Sood73 Community-engaged methods that include stakeholders as partners or advisors can help to ensure that stakeholder perspectives are incorporated into all phases of research, including identification of priority health concerns and research questions. Reference Israel, Eng, Schulz, Israel, Eng, Schulz and Parker74 Shifting the focus towards consideration for what is meaningful and significant to various stakeholder groups could help to better identify risks at critical developmental stages, optimal targets of intervention, and mechanisms of change.

-

(2) Identify variables that balance the needs of clinical practice and research and predict meaningful functional outcomes for families and other stakeholders

Variable selection for research trials and registries should be informed by and balance the needs and perspectives of the clinician and family stakeholders. As an example, both continuous and categorical variables are important to clinical practice and research but may serve different purposes for various stakeholder groups. Continuous variables allow investigation of subthreshold symptoms, Reference Chumra Kramer, Noda and O’Hara75–Reference Helmchen and Linden78 are necessary for measuring some domains without a corresponding diagnosis (e.g., visuospatial skills, memory, executive functioning), and allow for the study of psychological networks (i.e., symptom constellations) that may not fit categorical diagnoses. Reference Borsboom79 In contrast, categorical variables, such as specific diagnoses, may be preferred by clinicians in some areas, Reference DeMaso, Calderon and Taylor31,Reference DeMaso, Labella and Taylor32 especially for diagnoses that require early targeted intervention (e.g., autism spectrum disorder). As discussed above, there are increasing challenges to the categorical diagnostic framework for psychological disorders. Evidence from genetics and neuroscience suggests that symptoms are dimensional and occur in dynamic inter-related networks that may be present in more than one clinical category or disorder. Reference Carlew and Zartman80,Reference Kim and State81 This is especially relevant to those with CHD who do not clearly meet clinical criteria for an established neurodevelopmental or psychological diagnosis, but whose symptoms significantly impact day to day life (e.g., quality of life, peer relations, and educational/vocational attainment).

-

(3) Identify neurodevelopmental and psychological assessment tools that balance the needs of clinicians, researchers, and families

Assessment tools need to identify neurodevelopmental and psychological concerns in an efficient and cost-effective manner, without sacrificing psychometric rigour and sensitivity. Some instruments may be preferred by researchers, but can be problematic for clinical practice. Clinician and family stakeholders should be engaged in the process of selecting assessment tools for research trials and clinical registries to ensure that results are clinically meaningful for various stakeholder groups. Reference Israel, Eng, Schulz, Israel, Eng, Schulz and Parker74

-

(4) Examine meaningful outcomes with statistical analyses that consider individual factors, longitudinal change, and dynamic latent variables

Statistical methods that can specifically evaluate meaningful differences should be utilised, Reference Pugliese, Anthony and Strang82 including those that examine individual-level variables and their association with a child’s outcome across time while controlling for important factors (e.g., disease severity, family factors, Reference Harrison and McLeod83 comorbidities). Statistical analyses should also consider latent factors Reference Peterson, Boada and McGrath84 in order to better understand complex neurodevelopmental and psychological constructs and the relationships between them. Reference Daley and Birchwood85,Reference Sabol Tierri and Pianta86 The interaction between outcome domains (or symptoms) Reference Hong, Dwyer and Kim87,Reference Wilms, Kanowski and Baltes88 or how networks of overlapping symptoms present as comorbidities Reference Cramer, Waldorp and van der Maas35 is critical to understanding functional impact (e.g., executive functioning affects adaptive skills that affect adult transition; Reference Jackson, Gerardo and Monti89 behavioural regulation affects academic functioning Reference Cassidy, White and DeMaso61,Reference Sanz, Wang and Berl67 ).

Critical question 4: What factors predict resilience and are protective in individuals with CHD across the lifespan?

Existing knowledge

Resilience has been defined as “a universal capacity which allows a person, group or community to prevent, minimise or overcome the damaging effects of adversity.” Reference Newman and Blackburn90 Individuals with CHD and their families often experience challenging, threatening, and traumatic experiences related to their medical condition, especially those with more complex disease. An understanding of factors that improve patient and family coping and resilience has the potential to positively impact the psychosocial well-being, physical health, and neurodevelopment of children with CHD. These factors could be closely monitored and leveraged across development to better inform and drive interventions.

Most outcome research among children with complex CHD focuses on impairments or problems related to psychological adjustment, development, cognition, or quality of life, and on specific risk factors for these problems. Only a smaller number of studies have focused on resilience. For example, several studies have found that positive self-concept is associated with better psychosocial adjustment, higher quality of life, and decreased depression for adolescents with CHD. Reference Cohen, Mansoor and Langut91–Reference Salzer-Muhar, Herle and Floquet93 Other studies have also reported that positive self-perceptions regarding global self-worth, competence, and health were associated with better adjustment, Reference Mussatto, Sawin and Schiffman92 and higher levels of social support can mitigate stress and contributed to better behavioural outcomes. Reference Visconti, Saudino and Rappaport94

Research with patients and families facing other chronic illnesses or trauma has identified several possible factors that predict resilience or positive outcomes. For example, positive family functioning mediates the relationship between family “hardiness” (a family’s ability to respond to stressful life events) and caregiver state anxiety. Reference Nabors, Kichler and Brassell95 Higher levels of social connectedness in multiple domains (neighbourhood, friend, parent, sibling, school, peer, and teacher) were associated with lower stress and better coping (such as “benefit finding” or perception of personal growth). Reference Howard Sharp, Willard and Okado96 Similarly, research studies on the experience of adverse childhood events have identified several factors associated with the development of resilience, including a positive appraisal style, good executive functioning, nurturing parenting, maternal mental health, good self-care skills, consistent household routines, as well as an understanding of trauma. Reference Traub and Boynton-Jarrett97 Continuing to identify positive predictive factors will be critical to monitoring and intervention strategies.

Significant gaps in knowledge

While some information exists regarding risk and protective factors associated with resilience, literature specific to the CHD population is less developed, leaving significant gaps in knowledge regarding possible factors that promote resilience in children with CHD. We need additional research to identify factors such as positive family functioning, parental mental health (including fathers Reference Sood, Karpyn and Demianczyk98 ), and engagement with social support systems that are associated with resilience and to better understand their role in families and patients with CHD.

Investigations needed

-

(1) Identify specific factors that predict resilience and positive outcomes for individuals with CHD and their families

Future research should focus on identifying specific characteristics of individuals with CHD associated with resilience and optimal neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes, particularly those characteristics that are modifiable. Literature on resilience in other paediatric medical conditions and adverse childhood events will likely help to identify promising characteristics that can be evaluated among patients and families with CHD, including social support, positive self-concept, and positive coping strategies. Reference Howard Sharp, Willard and Okado96,Reference Traub and Boynton-Jarrett97,Reference Rolland and Walsh99

-

(2) Examine the development of resilience and interactions among resilience and risk factors over time

As with neurodevelopmental outcomes, studies examining resilience tend to conceptualise it as a static variable. Instead, resilience could be conceptualised as a skill that develops and varies over time in a child/family, is influenced by other variables in a developmental cascade, Reference Cox, Mills-Koonce and Propper55,Reference Masten and Cicchetti56 and plays a role in the previously described complex networks/constellations of neurodevelopmental outcomes. Longitudinal models should include those factors that have been shown to promote resilience and positive outcomes for individuals with CHD or other paediatric medical conditions. Models also need to evaluate potential interactions among resilience and risk factors over time, how these interactions may influence later outcomes, and how to approach strategies for intervention.

Critical question 5: How do we engage diverse populations with CHD to better understand neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes?

Existing knowledge

The population of the United States is growing more diverse, and it has been predicted that white children will be the minority population after 2020, and white adults will be the minority in 2044 Reference Flores100 (United States Census Bureau 2014 Projections). Improved understanding of meaningful neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes for diverse individuals with CHD across the lifespan is critical and will allow providers to better communicate and partner with families, identify risks and resilience, improve referrals to developmental services/supports, and plan treatment, thereby improving neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes.

Most commonly used measures of neurodevelopmental and psychological functioning were developed primarily within a normative sample of non-Hispanic, white middle class individuals, and derived from western cultural norms that are not necessarily generalisable across other cultures. Reference Manly101–Reference Rosselli and Ardila103 The skills and abilities considered important within the western culture for whom the tests were developed may have limited value or salience in other cultures. Reference Manly101 In the United States alone, there is also significant heterogeneity between and within cultural groups, which further limits the generalisability of these measures among diverse populations. Reference Mikesell, Bromley and Khodyakov104 Among populations whose primary language is not English, translations of existing measures may not provide for cultural equivalency and may further decrease validity and reliability. Reference Norbury and Sparks102 For example, development and/or translation of a measure derived from a normative sample of Spanish speakers from Mexico is not likely to apply to a normative sample of Spanish speakers from Nicaragua or Cuba. Reference Llorente and Llorente105 Moreover, the identification of nonverbal tasks as more “culture-fair” measures of cognitive functioning is misleading. Performance differences are common in diverse groups, Reference Rosselli and Ardila103 and many of these tests lack cultural relevancy.

In addition, there have been longstanding challenges with recruitment and retention of diverse populations in research and clinical care. There are likely a host of contributing factors, including lack of diversity within institutions, barriers to care (e.g., insurance, geographical), difficulty scheduling because of parent work and/or child’s school schedule, distrust of the medical system due to historical racism and abuses, and lack of understanding about the purpose and potential benefits of research, which may limit recruitment and retention of culturally and linguistically diverse participants. Reference Manly101,Reference Byrd, Arentoft and Scheiner106 Nonetheless, guidance is available in the literature about overcoming barriers to recruiting and retaining diverse populations for research studies. Reference Mikesell, Bromley and Khodyakov104,Reference Arevalo, Heredia and Krasny107–Reference Haley, Southwick and Parikh110

Significant gaps in knowledge

There are few studies examining normative performance on measures of intellectual skills and cognitive functioning among bilingual or culturally diverse children, and no studies have been published specifically within the CHD population. Thus, it is unclear if test performance discrepancies exist among patients from diverse versus majority cultural backgrounds or, if they do, what are the underlying causes/contributors. Furthermore, little information is available about demographic variability among participants versus non-participants in existing studies and whether differences in clinical outcomes exist. This limits the generalisability of findings to the larger CHD population. To date, there is only one published study designed to explicitly examine some of the socio-economic, educational, and ethnic disparities that may impact access to neurodevelopmental follow-up in children with CHD. Reference Loccoh, Yu and Donohue111 Understanding the unique contribution of diversity on neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes, as well as physical health, is critical to the development of viable intervention programmes and outreach for affected individuals and their families.

Investigations needed

-

(1) Increase the number of racially, socially, and geographically diverse participants with CHD in neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes research

Future investigations should oversample minority and underrepresented populations to ensure sample sizes are statistically powered for subgroup analyses. Future studies should also conduct qualitative and mixed-methods analyses to elucidate facilitators and barriers to participation of underrepresented racial, ethnic, and underserved populations with CHD in neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes research Reference Erves, Mayo-Gamble and Malin-Fair109 . To facilitate greater success in inclusive research and inform future clinical and community-based studies, it is critical to involve community stakeholders in research design and recruitment, include bilingual and diverse research staff to better support inclusion efforts, include appropriate incentives such as childcare or evening hours for participation, and use a community-based rather than centre-based study design. Reference Mikesell, Bromley and Khodyakov104,Reference Arevalo, Heredia and Krasny107–Reference Haley, Southwick and Parikh110

-

(2) Improve our measurement of neurodevelopmental and psychological variables and other important contributing variables

Future investigations should include additional variables that better represent constructs from racially and ethnically diverse populations, such as quality of education and test-wiseness, acculturation, and language dominance/proficiency, which will improve identification of factors that may influence test performance above and beyond actual neuropsychological impairments. Reference Rivera Mindt, Arentoft and Germano112–Reference Shuttleworth-Edwards114 In addition, studies explicitly designed to assess the psychometric properties of assessment tools, utility of race/ethnic based norms, and statistical approaches to data analysis in cross-cultural and longitudinal assessment are needed. This will allow for clarification as to whether constructs measured by these tests are the same for ethnically diverse populations Reference Rivera Mindt, Byrd and Saez115 and to help in the development of best practice guidelines for analysis of longitudinal trajectories within racially and ethnically diverse populations with CHD (e.g., regression-based norms, estimation of direct and indirect effects, biases in ceiling and floor effects, etc.). Reference Glymour, Weuve and Chen116,Reference Pedraza and Mungas117

-

(3) Identify best practices for the evaluation of language dominance/proficiency for bilingual individuals.

As Spanish-English bilinguals represent a large underrepresented group in the United States Reference Ryan118 , a better understanding of this group is a high priority and could inform clinical practice and research with speakers of other languages. Within the Spanish-speaking population, availability of reliable and valid Spanish language tests is necessary along with careful consideration of the child’s current language proficiency in English and Spanish. Level of acculturation in child and primary caregivers and geographical region of origin should also be explored in order to identify the most appropriate assessment tools. Reference Rivera Mindt, Arentoft and Germano112

-

(4) Identify cross-cultural clinical training needs among providers within the CHD community

Both within adult and paediatric neuropsychology, proposed guidelines and recommendations for improved practices have been published, Reference Olson and Jacobson113,Reference Rivera Mindt, Byrd and Saez115,Reference Brickman, Cabo and Manly119,Reference Judd, Capetillo and Carrion-Baralt120 but it remains unclear how widely used these are, and if a standardised approach is the norm. To our knowledge, there has only been one recent survey of neuropsychology or other child/paediatric psychology practices with regards to assessment of diverse patients. Reference Elbulok-Charcape, Rabin and Spadaccini121 Studies evaluating current practices among centers, as well as investigations of the feasibility and effectiveness of previously proposed standardised practices, are needed to create valid and reliable procedures that may be systematically applied across centers and within the diverse CHD community.

Discussion and conclusions

We have identified five critical questions that will improve characterisation of the neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes in CHD, and thus improve patient outcomes. These critical questions revealed a number of shared themes to guide future research.

First, it is necessary to shift our conceptual framework away from a static model (e.g., a unitary “neurodevelopmental signature”) to a more dynamic framework that includes a range of neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes conceptualised as a network of symptoms that interact and evolve over time. This conceptual framework provides a number of advantages in that it aligns with newer conceptual models in behavioural health and neurodevelopmental disorders, allows us to integrate outcomes research with other critical content areas (such as research in genetics and neuroscience), and moves us towards the era of personalised precision medicine. Reference Cuthbert37,Reference Casey, Oliveri and Insel39,Reference Carlew and Zartman80

To this end, there is a call towards developing a consensus on how to best measure key components of neurodevelopmental and psychological outcomes in CHD. Tools should be used that have good clinical utility and that are sufficiently sensitive and specific to identify known weaknesses in screenings and comprehensive assessments. At the same time, their psychometric properties should be strong enough to provide rigor in research, particularly in longitudinal research that tracks key skill areas over the course of development. There is also a substantial need to identify measures with good cultural and linguistic sensitivity, or to identify alternate, but comparable means of assessing key constructs in diverse populations.

Another common theme is a discussion of what is important and to whom. We need a better understanding of which aspects of neurodevelopmental and psychosocial outcomes are most important to the patients and their family and to their overall quality of life. Input from multiple stakeholders will be critical to answering these questions, and in particular, increased representation of patients, families, and diverse populations is needed. Our findings should directly inform the development of specific interventions and preventative strategies at sensitive and critical stages across the lifespan. In addition to traditional research methodologies, implementation of quality improvement and treatment trials will be important to more effectively improving the lives of our patients and families.

Finally, the optimisation of short- and long-term outcomes for individuals with CHD across the lifespan depends on continued scientific discovery and translation to clinical improvements in a coordinated effort by multiple stakeholders. While high-quality single-centre research will continue to be important, there is also a need to move towards multicentre research. Future investigations in the field will benefit from establishing linkages through multicentre collaborative quality improvement and/or research initiative and clinical registries. For example, the Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Outcome Collaborative clinical registry, which launched in 2019 as a module of the Pediatric Cardiac Critical Care Consortium and Pediatric Acute Care Cardiology Collaborative registries, will ultimately align data, expertise, and resources to improve clinical and functional health outcomes for patients with CHD and their families. This shared data repository represents an opportunity to advance the multicentre, longitudinal, multidimensional integration of data in our rapidly growing field, while minimising redundancy and duplication Reference Gaies, Anderson and Kipps122 . Ultimately, this would enable us to comprehensively describe the developmental and psychosocial trajectories of our patients, to identify potentially modifiable predictors of outcomes, and implement interventions to support needs.

Acknowledgements

The members of the Neurodevelopmental and Psychological Outcomes Working Group would like to thank Adam Cassidy, Jennifer Butcher, Cheryl Brosig, Gil Wernovsky, and the Publications Committee of the Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Outcome Collaborative for their thoughtful review of this manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant number 1R13HL142298-01).

Conflicts of interest

None.