Patients with congenital cardiac disease require lifelong medical care. The frequency of such disease in the population is approximately one percent. The population of the United States of America is approximately 295 million. Consequently, at a minimum, the number of surviving citizens in the United States with congenital cardiac disease is estimated to be between one and 2.9 million.

The milestones for surgical correction of congenitally malformed hearts include ligation of the patent arterial duct in 1938, repair of aortic coarctation in 1944, and construction of the Blalock-Taussig shunt in 1945. The introduction of cardiopulmonary bypass revolutionized surgical treatment in the 1950s. This technology facilitated successful repair of anomalies such as ventricular septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, and atrioventricular septal defect. In the 1970s, the Fontan procedure was introduced for patients with functionally univentricular circulations, and by the 1980s, advances in surgical technique and neonatal and paediatric intensive care units resulted in success of complex operations performed in the neonatal period, such as the arterial switch procedure and the first stage of Norwood palliation for hypoplasia of the left heart.

In the current era, we have an increasing population of adults with congenitally malformed hearts, with limited medical and surgical expertise to minister to their unique needs. The population of adults with congenitally malformed hearts can include those previously operated on during infancy or childhood, or those with lesions unrecognized until later in life.

Current challenges that face practitioners who care for adults with congenital heart disease include:

• identifying the best location for procedures, which could be a children’s hospital, an adult hospital, or a tertiary care facility,

• providing appropriate antenatal management of pregnant women with congenitally malformed hearts, and continuing this care in the peripartum period, and

• securing the infrastructure and expertise of the non-cardiac subspecialties, such as nephrology, hepatology, pulmonary medicine, and haematology.

The objectives of this review are:

• to outline the common problems that confront this population of patients and the medical community,

• to identify challenges encountered in establishing a programme for care of adults with congenitally malformed hearts, and

• to review the spectrum of disease and operations that have been identified in a high volume tertiary care centre for adult patients with congenital cardiac disease.

Recommendations about specific diagnoses and management plans are outlined in detail in the Guidelines provided by the American Heart Association, together with the American College of Cardiology, for the Management of adult patients with congenital cardiac disease and elsewhere.Reference Perloff1–3

Management of three common challenges in a practice dealing with adult congenital cardiac disease

Our three chosen examples of the fundamental problems facing the practitioner and patient in the United States of America in 2007 are:

• the neglected patient with congenital cardiac disease,

• weak infrastructure for adults with congenital cardiac disease, and

• family planning and management of pregnancy for patients with congenital cardiac disease.

The neglected patient

We use two representative histories to illustrate this problem.

Our first patient was a 31-year-old woman born with tricuspid atresia, who had undergone an atriopulmonary Fontan procedure at the age of 6. She was lost to follow-up from the ages of 15 to 29. When she reached 29, she developed atrial flutter and was electrically cardioverted. She went on disability from her employment, and subsequently developed exercise intolerance and ascites. She was referred for heart and liver transplantation, despite normal liver synthetic function and normal systolic ventricular function. Accordingly, she was a candidate for a revision of her “oldstyle” Fontan, and underwent conversion to an extracardiac conduit Fontan with an associated Maze procedureReference Backer, Deal, Mavroudis, Franklin and Stewart4. Her physical capacities were transformed, as was her quality of life, and her burden of medication was reduced. This patient exemplifies the problems that can exist when the physicians providing initial care do not understand the complexity of congenital cardiac disease, and the patient, along with his or her family, do not appreciate the need for expert care, and do not understand how to find it. In this case, the physicians providing initial treatment did not understand the Fontan circulation. This problem was compounded by the fact that the patient and her family did not know that she needed expert care, or how to find it.

Our second example is a 28-year-old man who underwent repair of tetralogy of Fallot at the age of 5. He had been followed-up in the community since the age of 16. He had an aborted cardiac arrest when he was 21, and an internal cardiac defibrillator was placed at the age of 22. Three years later, he developed atrial flutter. He was then referred to an expert in adult congenital cardiac disease. His electrocardiogram showed a QRS complex with a duration of 200 milliseconds, a risk factor for ventricular tachycardia and sudden death. His echocardiogram showed severe pulmonary regurgitation, severe right ventricular dilation, systolic dysfunction, and moderate tricuspid regurgitation. He was referred for replacement of his pulmonary valve, repair of the tricuspid valve, and a right atrial Maze procedure. He required additional electrophysiologic ablative procedures. His life was transformed by these interventions, and he had not felt so well or so physically capable for over 10 years. He wondered why he had not had surgery earlier. His experience exemplifies the problems that can exist when the patient and his or her family are not taught about potential future problems associated with their congenital disease, and what surveillance care is necessary. In this case, the patient and his mother had not learned what might happen in his future, and what surveillance and care he needed. His community cardiologist did not recognise the need to refer him to expert care. His electrophysiologist did not understand “mechanoelectric relationships”, in other words, that cardiac arrhythmias often reflect underlying haemodynamic problems, and did not arrange an informed haemodynamic assessment.

Patients with adult congenital cardiac disease often do not receive appropriate surveillance.Reference Warnes, Liberthson and Danielson5 There are three fundamental reasons for this problem:

• most adults with congenitally malformed hearts have been lost to follow-up by specialists, and are either receiving community care or no care at all,

• patients and their families have not been educated about their malformed hearts, what to expect, and how to protect their interests most effectively,Reference Knauth, Verstappen, Reiss and Webb6 and

• adult physicians have not been educated about the complexity of the adult with a congenitally malformed heart.

This combination can be fatal for adults with complications related to their congenitally malformed heart, or its prior treatment.

Two solutions would improve surveillance and care for the next generation of patients coming out of the care of paediatric cardiologists. The first would be to educate patients and their families during childhood and adolescence.Reference Verstappen, Pearson and Kovacs7 They would learn the names of the diagnoses and treatments, problems to anticipate and avoid, the importance of expert surveillance, career and family planning information, and appropriate self-management. Such an educational process would hopefully reduce the percentage of patients lost to follow-up during the childhood and adolescent years. The second solution would be to encourage an orderly transfer of patients from paediatric to adult practice. In countries with a history of organized follow-up for adults with congenitally malformed hearts, transfer is usually at about 18 years of age, and at the time of graduation from high school.

Weak infrastructure

In Canada, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, as well as some other countries, specialized clinics for adult patients with congenitally malformed hearts have now existed for a generation or more. When these countries began to organize care for these patients, they faced the same problems with infrastructure currently being faced in the United States of America. While the care of patients with congenital cardiac disease in the United States of America has been excellent in childhood and adolescence, in most parts of the country there has been no tradition of developing equivalent services for adults with congenital heart disease. Care of these patients is not concentrated, so medical students and physicians seldom have the opportunity to learn about their diagnosis and management. For the same reason, there is a gross shortage of sonographers and echocardiographers skilled in their assessment, even in otherwise excellent echocardiographic laboratories. There is a dearth of nurses familiar with these patients, and able to contribute importantly to their care. Clinics for adults with congenital cardiac disease depend upon multidisciplinary collaboration with specialties in areas such as congenital cardiac imaging, diagnostic and interventional catheterization, congenital cardiac surgery and anaesthesia, heart failure, transplantation, electrophysiology, reproductive and high risk pregnancy services, genetics, pulmonary hypertension, hepatology, nephrology, haematology, and others. None of these services are easily available “off the rack,” although with time, experience, and determination these services can develop very well.

Moreover, an orderly plan does not exist to train the personnel needed to staff the clinics that are developing for these patients in the United States of America.Reference Child, Collins-Nakai and Alpert8, Reference Landzberg, Murphy and Davidson9 There are very few credentialed programmes training cardiologists, sonographers, or nurses in adult congenital cardiac disease. At present, there are insufficient strong programmes within the United States to expand this training, even if funding were available to do so. Many physicians and nurses working in clinics for adults with congenital heart disease in the United States are dedicated to the care of their patients, but have not had the benefit of a strong education in this subspecialty, as can be had in other parts of the world. The situation is improving, and will take some time to develop and mature. The Adult Congenital Heart Association is a patient advocacy group that now has more than 60 clinics for adults with congenital heart disease listed on their web site: www.achaheart.org. Most of these programmes are less than five years old. The development of these facilities by experienced personnel indicates that competent care for adults is becoming increasingly available. Parents and patients should learn that these facilities exist, and be directed to one by their paediatric caregivers when the time comes for transition to adult care.

Contraception and pregnancy

There are now over one million living American adults with congenitally malformed hearts, and half are women. Most patients have not been counselled regarding contraception and family planning. Studies show that the cardiologist needs to take the lead in providing this information. There is reason to believe that few of us practising in cardiology have current information on the range of contraceptive options available so that we can best counsel our patients. Unexpected teenage pregnancy may trigger transfer to adult care. Some excellent articles have been published that review the principles of counselling patients with congenitally malformed hearts regarding contraception.Reference Thorne and MacGregor10, Reference Thorne, Nelson-Piercy and MacGregor11

With the steady increase in the number of adults with congenital heart disease, an ever increasing number of women with such disease are becoming pregnant. Services are not widely available to assess competently and plan a pregnancy for those with more complex disease. It is essential to have a close interplay between the obstetrician, the adult congenital cardiologist, the fetal medicine perinatologist, and neonatologist. Fortunately, two textbooks have just been published on the subject of adult congenital heart disease and pregnancy, and offer excellent information to the provider of health care.Reference Oakley and Warnes12, Reference Steer, Gatzoulis and Baker13 With the information provided in these books, the interested practitioner will be better prepared to improve the level of care for these patients.

Challenges in establishing a community programme for adults with congenital cardiac disease – the Tampa Bay experience

In Tampa Bay, Florida, in the United States of America, paediatric cardiologic care began in the 1970s with the arrival of two paediatric cardiologists, one in Saint Petersburg and one in Tampa. Approximately 20 years later, it became apparent that there was a need for specialized care for grown-ups with congenitally malformed hearts as described and recommended by the 22nd and 32nd Bethesda ConferencesReference Perloff1, Reference Webb and Williams2 as well as written about by groups in Los Angeles, Toronto, England and other parts of the world.

In Tampa Bay, paediatric and congenital cardiac care is provided by the Congenital Heart Institute of Florida. In 1993, the Tampa Bay Adult Congenital Heart Disease Clinic was established. This Clinic is the component of The Congenital Heart Institute of Florida that is responsible for care of the adults with congenital cardiac disease. The Tampa Bay Adult Congenital Heart Disease Clinic fulfils the needs of the Tampa Bay community to provide specialized care for adults with congenital heart disease, and to enhance the didactic requirements of the fellowship programme in adult cardiology at the University of South Florida College of Medicine. Initially, the clinic was held monthly, but as the programme grew, clinics were added. They are now held weekly in both Tampa and St. Petersburg.

The first challenge was to identify and recruit the efforts of qualified specialists in congenital heart disease available in the community. Local congenital and adult cardiovascular surgeons, electrophysiologists, high-risk perinatologists and other supporting care physicians joined efforts in a loose affiliation and cooperative effort to provide expert care. This professional collaboration created the critical mass necessary to spark the growth of the Tampa Bay Adult Congenital Heart Disease Clinic through referrals and community awareness. Patients have been transitioned to this clinic mainly from the pre-existing paediatric program of the Congenital Heart Institute of Florida, usually when they are between 18 and 21 years of age. In addition, patients have also been referred from local and regional adult cardiologists, obstetricians and gynaecologists, family practitioners, and internists in Tampa Bay and surrounding areas.

At present, the clinic serves approximately 400 adults with congenital heart disease in three outpatient locations. In our experience, providing service at the point of care greatly facilitates access and improves compliance with scheduled follow-up. These private practice outpatient-based clinics provide a dedicated nursing and allied health care staff, as well as comprehensive non-invasive diagnostic imaging and laboratory services that are provided at the time of evaluation. Should urgent inpatient care be required, hospital admission with rapid access to appropriate medical and surgical services can be provided. Coordination of care with experienced subspecialists remains challenging. Efforts are in progress to address this issue by identifying and incorporating mid-level providers or care coordinators who have an interest in the management of adults with congenital heart disease. This accomplishment, in addition to established referral patterns, will further improve the overall services offered to these patients.

We show the demographics of the age of the patients seen in the clinic in Figure 1. The population is relatively young, with a large percentage aged from 20 to 29 years, and a smaller percentage aged from 30 to 59 years. The mix of diagnoses is similar to other reports concerning adults with congenital heart disease.Reference Williams, Child, Kuehl, Myerson, Sahn and Webb14 Two-fifths of the population is accounted for by 4 major diagnoses, namely tetralogy of Fallot, transposition, tricuspid atresia, and other forms of functionally univentricular heart (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the majority of these patients are quite functional despite the presence of complex congenital cardiac disease (Fig. 3). Of the patients followed in the clinic, seven-tenths are employed. Importantly, we have also noted that the majority of patients are motivated to want a “normal” life.

Figure 1 Age distribution of 312 patients in the Tampa Bay Adult Congenital Heart Clinic of The Congenital Heart Institute of Florida.

Figure 2 Distribution of diagnoses in 292 patients seen at the Tampa Bay Adult Congenital Heart Clinic of The Congenital Heart Institute of Florida.

Figure 3 Functional class of patients in the Tampa Bay Adult Congenital Heart Clinic of The Congenital Heart Institute of Florida.

An additional challenge has been issues of insurance. Although most have either commercial insurance, or Medicare or Medicaid, a substantial number, one-fifth, remain uninsured (Fig. 4). Lack of funding further hinders appropriate medical care when complex outpatient diagnostic testing is necessary, and when elective hospital admission for invasive testing is required. Hospital social workers have become more engaged with these concerns, and have been assisting and supporting the programme. The Tampa Bay Adult Congenital Heart Clinic, however, has made a commitment to provide diagnostic and therapeutic care to these non-funded patients.

Figure 4 Payer mix for 288 patients in the Tampa Bay Adult Congenital Heart Clinic of The Congenital Heart Institute of Florida.

Inpatient care has not been completely centralized. This situation is a result of congenital cardiac surgery, adult cardiac transplantation, and high-risk obstetrical services not being available inclusively in one centre. Currently, the physicians and health care providers composing the Congenital Heart Institute of Florida provide these services at geographically different institutions within the Tampa Bay community, specifically at All Children’s Hospital and Bayfront Medical Center in Saint Petersburg, and St. Joseph’s Children’s Hospital and Tampa General Hospital in Tampa. While inpatient services are somewhat decentralized, the best care available and the specific patient needs direct the selection of a particular hospital. Other factors considered include patient preference due to geographic considerations or requirements of insurance contracts. Although this geographical separation has been cumbersome for the providers of health care because of responsibilities for care of other patients in different locations, the final result assures the best match for a particular patient or condition with the appropriate hospital facility within the community. The addition of care coordinators to the three outpatient facilities will further assist in streamlining the inpatient experience for both the patient and family.

Expertise of the inpatient nursing and allied health staff have also evolved over the years. Difficulties include paediatric-trained personnel not being comfortable with adult patients and their medical problems, and adult-trained staff not being comfortable with congenital heart disease. Common examples include paediatric-trained personnel not being comfortable with selection of medications and different dosing regimes, as well as the management of medical comorbidities that frequently coexist in the adult patient, such as diabetes mellitus, and other endocrine, pulmonary, hepatic, or renal abnormalities. Conversely, adult-trained personnel may not be familiar with the anatomy and physiology of congenital heart disease and its potential implications, such as the possibility of an air embolism in the setting of an intracardiac shunt while flushing a simple intravenous line. Further experience, and focussing a smaller group of allied health professionals, will further improve the quality of care provided to this continuously increasing group of patients.

Despite these challenges, the Tampa Bay Adult Congenital Heart Program of The Congenital Heart Institute of Florida has obtained excellent outcomes. The catheterization, interventional, electrophysiology procedures account for one-tenth of the total procedures, and in the last decade there has been no mortality. In addition, the surgical volume and case complexity have both steadily increased. During the 5 years from 2002 through 2006 inclusive, the Congenital Heart Institute of Florida has performed on the average 796 cardiothoracic operations per year. The volume of adults requiring surgical correction for congenital heart disease comprised 6% of the total surgical volume over the last decade, with an overall early mortality of 2.3%, which is identical to that reported in the database of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (Fig. 5). Common operations include late insertion of a pulmonary valve for patients with tetralogy of Fallot and pulmonary insufficiency, often using a novel bicuspid polytetrafluoroethylene pulmonary valve that was developed by our surgical team, and has been inserted in over 90 patients,Reference Quintessenza, Jacobs, Chai, Morell, Giroud and Boucek15, Reference Quintessenza, Jacobs, Morell, Giroud and Boucek16 as well as revision of the Fontan circulation, with conversion of a prior classical Fontan circuit to the total cavopulmonary connection accompanied by a Maze procedure,Reference Backer, Deal, Mavroudis, Franklin and Stewart4 and a variety of other valvar repairs and replacements, and replacements of conduits.

Figure 5 Discharge mortality following cardiac surgery from the database of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons for the years 2002 to 2005 inclusive. It is notable that mortality is highest in neonates, then decreases in infants, decreases more in older children, but then increases again in the population of adults with congenital heart disease.

Future efforts will focus on expanding the inpatient and outpatient infrastructure, centralization of inpatient services, expanding the role of care coordinators, and emphasizing patient and family education, continued follow-up, activity levels, and planning of pregnancies. In addition, new recruitments will include individuals with formal training and exposure to adults with congenital heart disease, either from the paediatric cardiology pathway, or from adult cardiology with subsequent training in adult congenital heart disease.Reference Deanfield, Thaulow and Warnes17

Spectrum of adult congenital cardiac disease in a centre providing tertiary care – the Mayo Clinic experience

Between March 1, 1955, and January 1, 2007, at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, in the United States of America, 5,747 patients aged 18 years and older have undergone operations to correct a congenital heart defect, excluding patients with a bicuspid aortic valve and those with a defect within the oval fossa, or an “ostium secundum” atrial septal defect. The majority of patients are aged from 21 to 40 years (Fig. 6). The number of such adults undergoing surgery at the Mayo Clinic over the last 14 years has steadily increased (Fig. 7). The early mortality for this group of 2,851 consecutive operations in the 14 years from 1993 to 2006 inclusive was 2.4%.

Figure 6 Age distribution of patients in the Mayo Adult Congenital Heart Clinic.

Figure 7 Number of operations for adults with congenital heart disease performed at Mayo Clinic over the last 14 years.

A core multidisciplinary team of subspecialists in the Congenital Heart Center at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, are fully trained to care for patients with congenitally malformed hearts. This includes 12 congenital cardiologists, 4 surgeons, 5 anaesthesiologists/intensivists, 1 radiologist, 2 electrophysiologists, and 3 interventionalists. Of the 12 cardiologists, 6 are dedicated and specially trained to care for adults with congenital cardiac disease. There are also two nurses trained in cardiology working in the outpatient clinic, where approximately 4,000 patients are followed. These nurses, experienced in congenital heart disease, are an integral part of the team, providing a source of advocacy for the patients, as well as education of anatomy and potential residual lesions. They also reinforce the importance of regular follow-up, endocarditis prophylaxis, and provide information regarding available community and national resources. Representatives from medical subspecialties, including hepatology, pulmonary hypertension, and maternal and fetal medicine, are available for inpatient and outpatient consultations. Each has developed an interest and focus in the care of adults with congenital heart disease. There is a dedicated intensive care unit with 11 beds for patients having surgery for congenital cardiac disease, which is equipped to manage patients requiring mechanical circulatory support, including extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and ventricular assist devices, as well as transplantation. This unit is staffed by nursing and allied health care providers who are specifically trained in the care of patients with congenital heart disease, both children and adults.

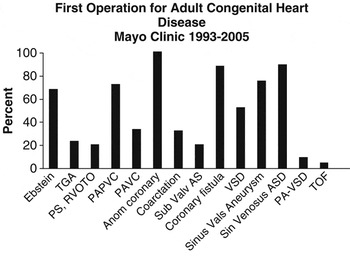

The spectrum of adult congenital cardiovascular operations, both primary and repeat, is shown in Figure 8. Operations are commonly performed for diagnoses such as Ebstein’s malformation, reoperations for replacements of conduits or pulmonary valves, aortic coarctation, and to relieve obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract (Fig. 9). A wide variety of valvar procedures, both repair and replacement, are relatively common in this population and involve all four cardiac valves. Interestingly, the need for concomitant coronary arterial bypass grafting at the time of repair of the congenitally malformed heart was not uncommon. Primary operation, that is the first operation being performed beyond 18 years of age, occurred often, and for a wide spectrum of disease (Fig. 10).

Figure 8 Operations stratified by diagnosis for adults with congenital heart disease performed at Mayo Clinic over the last 14 years.

Figure 9 Operation stratified by procedure for adults with congenital heart disease performed at Mayo Clinic over the last 14 years.

Figure 10 First operation in adulthood stratified by diagnosis at Mayo Clinic over the last 14 years.

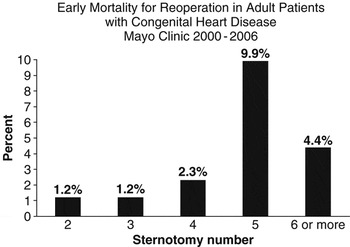

Monumental advances in the surgical management and perioperative care of neonates and infants with complex heart disease has resulted in the majority of these children living well into adult years. While many of these operations were initially viewed as “curative or corrective,” such as repair of tetralogy of Fallot or atrioventricular septal defect, many patients will require reoperation in the future for progressive valvar dysfunction, arrhythmias, or for other causes. There are other “corrective” operations, such as repair of common arterial trunk, and the Rastelli procedure, that will require reoperation because of degeneration of conduits or valves, or the eventual development of patient-prosthetic mismatch because of somatic growth. Examples include replacement of valves for Shone’s complex or Ebstein’s malformation. The lifelong need for additional procedures following palliative operations, such as after the Fontan procedure, is also well documented. Numerous reoperations may be required over the course of a lifetime, and the number of previous operations performed when a reoperation is being considered is increasing (Fig. 11). The early mortality related to repeat sternotomy is shown in Figure 12.

Figure 11 Numbers of sternotomies for adults with congenital heart disease undergoing operation at Mayo Clinic over the last 7 years.

Figure 12 Early mortality for reoperation stratified by sternotomy number at Mayo Clinic. Total number of operations for sternotomy # 2, n = 985; #3, n = 343; #4, n = 219; #5, n = 111; # > 6, n = 90.

The nuances and complexities of congenital cardiac anatomy, coupled with the high probability of previous operation during childhood, makes the trained congenital cardiothoracic surgeon best suited to deal with this growing population. The guidelines provided by the American College of Cardiology together with the American Heart Association3 recommends that adults with congenitally malformed hearts be operated on by cardiothoracic surgeons who have had additional training in “congenital” heart surgery and certification of added qualification.

Looking down the road

The adult with a congenitally malformed heart may not truly be “born to be bad” as has been suggested,Reference Warnes18 but it is clear that the vast majority of patients are not “cured” and require lifelong comprehensive care from specialists who have expertise in this complex arena.

During the next decade, we need to remedy some of the chronic structural problems that have faced adults with congenital heart disease in the United States of America. There is evidence that there is a growing cadre of healthcare professionals dedicated to improving the care of these patients. More information has become available about their care, and will be improved upon in the next decade. With the support of the general paediatric and paediatric cardiology communities, and of the Adult Congenital Heart Association, and with the persistence of the providers of care for adults with congenital cardiac disease currently staffing clinics nationwide, the care of these patients should become more secure in the next decade as we mature our capabilities.