Rheumatic fever remains the most common form of heart disease in the world due to its prevalence in the developing world and subsets of the population in the developed world, such as the indigenous Māori and Pacific Islanders in New Zealand. The diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever remains a clinical diagnosis based on major and minor criteria. 1 – Reference Neutze 4

Various conduction and rhythm disturbances have been associated with rheumatic fever. Abnormalities in atrioventricular conduction including first-degree heart block and more advanced degrees of atrioventricular block, junctional acceleration, supraventricular and ventricular tachycardia, bundle branch block, ectopic atrial and ventricular complexes, prolongation of the QT interval, and torsade de pointe have all been reported.Reference Karacan, Isikay and Olgun 5 – Reference Yahalom, Jerushalmi and Roguin 14

We present a 5-year retrospective review of confirmed acute rheumatic fever cases from our institution, focusing on presentations with advanced atroventricular block and junctional rhythms.

Methods

Patients under 15 years of age, satisfying the New Zealand Heart Foundation 2014 definition of rheumatic fever, 1 presenting to KidzFirst Children’s Hospital in South Auckland between January 2010 and December 2014 were retrospectively identified from a regional Rheumatic Fever Registry. Patients were excluded if they had incomplete data sets or if they were registered for chronic or indolent rheumatic heart disease.

Patient age, gender, NZ Heart Foundation 2014 major criteria, initial erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein, and streptococcal titres (anti-streptolysin and anti-DNAse B antibodies) were collected from clinical and laboratory records. Electrocardiography data were analysed as described below.

Electrocardiographic analysis

Electrocardiograms (ECG) from the first week after presentation were analysed. The PR interval (lead II) and QTc (longest of lead II or V5) using Bazett’s formulaReference Park and Park 15 were calculated.

The presenting rhythm was categorised into the following three groups:

1. Advanced atrioventricular conduction abnormality (AAVCA) was used to describe our group of interest. This term included patients with either acquired second- or third-degree atrioventricular block or a junctional rhythm or any type.

Advanced atrioventricular block was defined as a second- or third-degree heart block.Reference Park and Park 15

Junctional rhythm was defined where in Lead II there is an absent p wave or a p wave that follows a normal QRS, where the ventricular rate was the same as or in excess of the atrial rate.Reference Park and Park 15

Ventriculoatrial dissociation was recorded when in the presence of a junctional rhythm, the atria and ventricle operated independently for more than three beats.Reference Park and Park 15

2. Prolonged PR: This included all cases with first-degree atrioventricular block.

3. Normal ECG: This includes all cases in sinus rhythm with normal PR interval.

Comparative data set

Local hospital data over the study period were reviewed to identify patients presenting with AAVCAs who did not satisfy a diagnosis of rheumatic fever using the International Classification of Disease Codes version 10. The total number of electrocardiographs performed during the study period was also determined.

To assess the utility of an electrocardiographic diagnosis of AAVCA in diagnosing acute rheumatic fever, we reviewed all admissions to our centre during the study period using a broad International Classification of Disease-10 Code search of conduction abnormalities.

Statistical analysis

The Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test of non-parametric data was used for continuous variables and the Fisher t test was used for categorical variables.

All p-values were two-tailed and a p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

There were a total of 16,135 admissions to our hospital over the study period, with a total of 3702 electrocardiographs performed during this time on children under 15 years of age. A total of 224 new cases of rheumatic fever were identified. Of these, 23 patients were excluded: 9 patients were registered as chronic or indolent rheumatic heart disease, 1 patient had an alternative diagnosis of septic arthritis, and the remaining 13 patients had incomplete data sets (no electrocardiographic data +/− a lack of adequate notes). The remaining 201 cases had an average age at presentation of 10.3 years (range 5–14 years), with 59% of patients being male. Missing data on included patents are recorded in Table 1. The distribution of major criteria at presentation can be found in Table 2. In total, 173 (86%) patients had clinical or subclinical carditis at presentation: 122 (61%) patients presented with clinical carditis and a further 51 (25%) cases had subclinical carditis. A total of 172 (86%) patients had two or more major criteria. We identified only one patient meeting our diagnosis of advanced conduction abnormality who did not have a diagnosis of rheumatic fever. This patient was a 12-year-old child from Zimbabwe, who presented with an idiopathic complete heart block at age 12 years. His echocardiogram was normal and he had no history consistent with Acute Rheumatic Fever.

Table 1. Missing data.

Table 2. Major diagnostic criteria.

Rhythm analysis

A total of 17 (8.5%) patients with acute rheumatic fever had AAVCA on ECG with the confirmation of diagnosis by the study paediatric electrophysiologist (JS). In total, 5 (2.5%) patients presented with advanced atrioventricular block; 3 patients with second-degree heart block (Mobitz type 1) and 2 with complete heart block. Junctional rhythm occurred in 12 (6%) patients. A total of four patients with junctional acceleration also had ventriculoatrial dissociation. Three ECGs that were initially included in the junctional acceleration group were later excluded as they were felt to demonstrate first-degree heart block with an extremely prolonged PR interval.

AAVCA presented with significantly higher ESR and C-reactive protein and significantly less carditis (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3. Comparison of AAVCA versus Prolonged versus Normal PR groups: continuous variables.

* P is p-value using the Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test to compare the three groups

p < 0.05 is considered significant

AAVCAs were a transient phenomenon in all patients, with a normal electrocardiograph documented either during the initial admission or in early follow-up. AAVCA took a variable time to resolve, usually days rather than weeks, and usually to sinus rhythm with first-degree block. The exact time was not able to be determined accurately in this retrospective review. No patients with an AAVCA developed cardiorespiratory instability or required treatment for their rhythm disturbance. We did not use corticosteroids Intravenous Immunoglobulin or aspirin for the treatment of rheumatic valvulitis or rhythm disturbance.

The PR interval was prolonged for age and heart rate (first-degree heart block) in 93 (46%) and normal in 91 (45%) of patients (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of AAVCA versus prolonged versus normal PR: discrete variables.

* P = p-value derived from the Fisher t test comparing the two groups

** p-value relates to all non-cardiac major criteria combined

p < 0.05 is considered significant

Comparative data set

From the total of 16,135 admissions, 92 admissions with a primary or secondary diagnosis of arrhythmia were identified from our International classification of disease search. These were reviewed, and patients with advanced atrioventricular block and junctional rhythm were identified. Patients with congenital, rather than acquired atrioventricular block, were then excluded. This left one patient with an acquired idiopathic complete heart block, who had a normal echocardiogram and did not meet criteria for acute rheumatic fever.

During the study period, a total of 3702 electrocardiographs were performed in children under the age of 15 years, presenting acutely to our children’s emergency department.

Illustrative case

Mesina, a previously well Samoan girl, aged 12 years presented acutely from her GP with a history of fever, lethargy, and chest pain. A throat swab taken 2 days prior isolated a moderate growth of group A streptococcus.

On admission, we obtained a history of a painful left ankle, but there was no objective evidence of arthritis. She was afebrile with normal findings on cardiac, respiratory, and skin examination. ESR was elevated at 90 mm/hour. Both anti-streptolysin and anti-DNase B antibodies were moderately elevated.

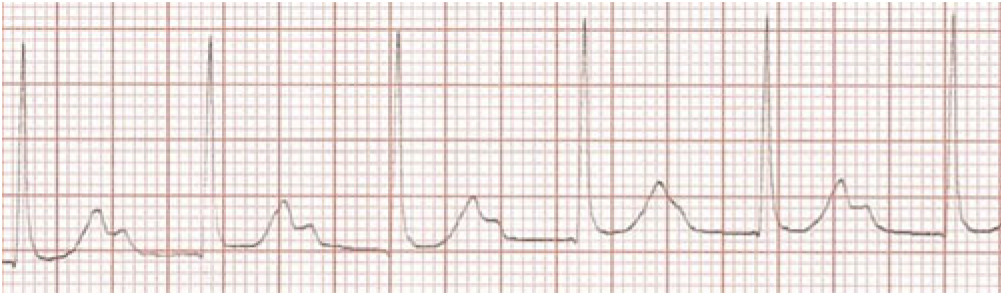

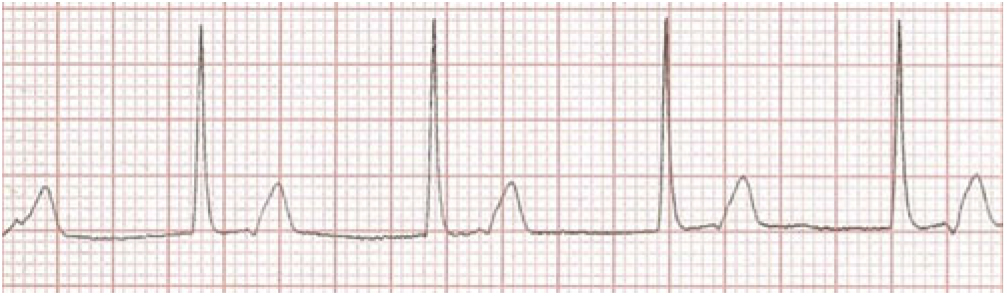

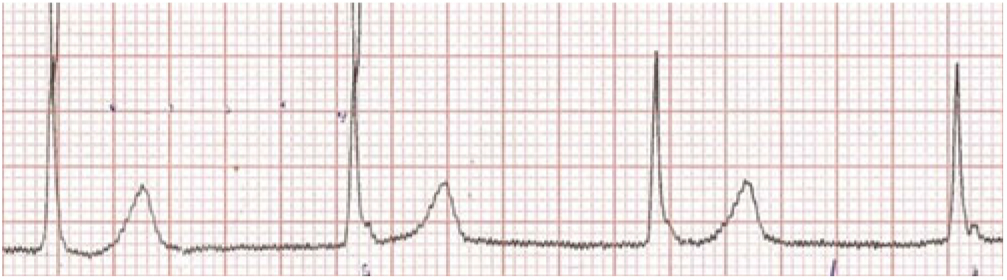

Her first ECG taken 1 hour after admission (Fig 1) at a heart rate of 89 bpm shows extreme PR prolongation with PR greater than 300 msecond. The P-waves are seen to merge into the T-waves. The second ECG (Fig 2) obtained 45 hours after presenting demonstrates an accelerated junctional rhythm at a rate of 71 bpm. The P-waves are seen in the ST segment following the QRS complex. On day 6 after admission, the third ECG (Fig 3) shows a junctional rhythm at 55 bpm. This was initially thought to represent complete heart block. By day 8, her ECG had returned to sinus rhythm at 57 bpm with a PR interval of 190 msecond. (All three ECGs are recordings from Lead II 10 mm/mV at 25 mm/seconds.)

Figure 1. Extreme PR prolongation,P waves merging with T waves

Figure 2. Accelerated Junctional rhythm at 71 bpm

Figure 3. Junctional rhythm at 55 bpm

Discussion

Rheumatic fever remains an important cause of cardiac morbidity for our New Zealand population, as well as other high-risk populations worldwide. 1 – Reference Neutze 4 There remains limited data on both conduction and rhythm disturbances in patients with acute rheumatic fever. We present a large contemporary cohort of acute rheumatic fever specifically addressing presentation with advanced atrioventricular block or junctional rhythms.

Prolongation of the PR interval is the most common finding in rheumatic fever, occurring in about 50%.Reference Karacan, Isikay and Olgun 5 – Reference Cristal, Stern and Gueron 9 , Reference Parkinson, Gosse and Gunson 16 , Reference Tani, Allen, Driscoll, Shaddy and Feltes 17 Despite its common occurrence, PR prolongation is not a specific sign of carditis; occurring in up to 2% of the normal population,Reference Ziegler 18 in patients following group A streptococcal throat infection who do not develop rheumatic fever,Reference Tani, Allen, Driscoll, Shaddy and Feltes 17 and with other febrile conditions. Hence, it remains as a minor criterion in the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever. We thus choose to exclude first-degree atrioventricular block.

Conduction abnormalities beyond first-degree heart block have been reported in case reports and small series. We choose to investigate patients presenting with advanced degrees of AV block or junctional rhythms on electrocardiograph both of which have been associated with acute rheumatic fever in small series. We identified 17 (8.5%) patients with these transient electrocardiographic abnormalities. Second- or third-degree atrioventricular block and junctional rhythm appear to be a temporary and self-limiting occurrence in acute rheumatic fever. Although reports of syncopal events and temporary pacing have been described complicating complete heart block in rheumatic fever, most reports indicate that the majority of patients will resolve without intervention being needed.Reference Carano, Bo and Tchana 19 Our data demonstrate all patients presenting with AAVCAs returning to sinus rhythm within days or weeks of diagnosis.

About 2.5% of our cohort demonstrated advanced atrioventricular block; three patients with second-degree heart block (Mobitz Type 1) and two with complete heart block. This is comparable to other reported incidence ranging from 1.5 to 5.5%.Reference Karacan, Isikay and Olgun 5 , Reference Balli, Oflaz and Kibar 7 , Reference Clarke and Keith 8 , Reference Zalzstein, Maor and Zucker 10

About 6% of patients presented with a junctional rhythm. This was defined by Karacan et al as narrow complex QRS rhythm, where the ventricular rate was the same as or in excess of the atrial rate.Reference Karacan, Isikay and Olgun 5 Junctional rhythm has an incidence in acute rheumatic fever of 5–15%, with the majority of patients (50–73%) showing ventriculoatrial dissociation on electrocardiograph.Reference Karacan, Isikay and Olgun 5 , Reference Clarke and Keith 8 We chose to include all patients with any form of junctional rhythm, who met Karacan’s definition, irrespective of rate as we surmised that any junctional rhythm during an acute presentation of rheumatic fever constituted an abnormality.

Diagnosis of junctional arrhythmia proved more challenging than the diagnosis of atrioventricular block, which was usually self-evident. Those presenting with junctional acceleration on ECG and little or no ventriculoatrial dissociation were often difficult to diagnose and required careful examination of the ECG. In our series, three ECGs that were initially thought to be junctional acceleration were later excluded upon review by the study of electrophysiologist, as they represented extreme first-degree atrioventricular block (see Fig. 1), resulting in P-waves “buried” in the T-waves.

Utility of AAVCA in the diagnosis of ARF

Ceviz et al compared patients with junctional acceleration to both a group of patients with confirmed group A streptococcal infection who did not develop acute rheumatic fever and a group of patients presenting with arthritis from rheumatic causes other than acute rheumatic fever. They found no patients with junctional acceleration in either of their comparison groups, suggesting this was likely a novel rhythm in acute rheumatic fever.Reference Ceviz, Celik and Olgun 6 We could not find any data regarding advanced atrioventricular block and the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever.

Acute rheumatic fever is endemic in our population, with one new diagnosis every 10 days on average. Our findings may not be generalisable, given that complete heart block is associated with other inflammatory conditions such as diphtheria, lyme disease, and myocarditisReference Phornphutkul, Damrongsak and Silpisornkosol 20 – Reference Sigal 22 which occur more commonly in other populations.

We chose to use all ECGs performed at our centre during the study period as a denominator for our analysis, but do not have data on the indications for why this test was ordered. Due to the endemic nature of rheumatic fever in our population and strict local protocols, we assume that all patients who presented with symptoms that could be consistent with acute rheumatic fever would have had an ECG and been included in this analysis. However, as less than 23% of patients admitted had an ECG during the study period, this limited our ability to detect asymptomatic patients admitted who may have shown an advanced conduction abnormality on ECG.

Both types of advanced conduction abnormality have previously been described with minimal other evidence of rheumatic carditis. Cristal demonstrated that advanced atrioventricular block is not consistently associated with valvulitis.Reference Cristal, Stern and Gueron 9 Karacan showed that junctional rhythms are not always associated with clinical carditis.Reference Karacan, Isikay and Olgun 5 Our study confirms their observations. Although AAVCAs are manifestations of cardiac involvement in rheumatic fever, they appear to occur earlier in the course of the illness, prior to the development of valvulitis, given the significantly higher ESR and C Reactive Protein we observed.

Limitations to this study

Despite collecting 5 years of data from our institution, we still only present small numbers of patients with both advanced conduction abnormalities due to the low incidence of these rhythms in rheumatic fever. Whilst there are limitations in identifying patients retrospectively, especially with what may be a secondary diagnosis, both advanced atrioventricular block and junctional rhythms are very uncommon in our population with the exception of children subsequently diagnosed with acute rheumatic fever. Our ability to collect a comparison population to assess their utility was also limited by our retrospective design. Prospective multi-institutional reviews or larger single institutional reviews are needed to ascertain sensitivity specificity and diagnostic accuracy of these abnormalities of conduction.

Conclusion

We present a large contemporary cohort of patients presenting with acute rheumatic fever in whom junctional rhythms and advanced atrioventricular block occurring in 8.5% of cases. We found that an electrocardiograph showing advanced conduction abnormality, beyond first-degree atrioventricular block, is highly suggestive of acute rheumatic fever. Clinicians should therefore consider a diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever in children, from endemic regions, with an electrocardiograph showing advanced conduction abnormalities when echocardiography is negative. Further prospective data were warranted to establish if advanced conduction defects could be used as a major criteria in the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever.

What is already known on this topic?

Advanced conduction abnormalities occur in up to 15% of rheumatic fever.

Conduction abnormalities can occur without evidence of rheumatic carditis.

What this study adds

An advanced conduction abnormality is highly suggestive of acute rheumatic fever in our population.

Advanced conduction abnormalities are commoner than erythema marginatum and subcutaneous nodules established major diagnostic criteria.

Author ORCIDs

William Nicholson 0000-0003-4190-0876

Acknowledgement

We thank Charlene Nell for preparing the manuscript and Pernille Christensen for statistical analysis.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Contribution statement

RN – Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. RN, JA, NW, and JS – Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. RN – Final approval of the version published. RN – Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.