Acute rheumatic fever is a well-known non-suppurative complication of the group A β-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis. Carditis is the most important clinical feature of the disease. Some electrocardiographic abnormalities can also develop. First-degree atrioventricular block is the most common and it is used as a minor diagnostic tool.Reference Ortiz1 Second- and third-degree heart block,Reference Stocker, Czoniczer, Massell and Nadas2–Reference Malik, Hassan and Khan7 junctional acceleration,Reference Cristal, Stern and Gueron8, Reference Olgun and Ceviz9 ventricular tachycardia,Reference Freed, Sacks and Ellman10 bundle branch blockReference Lenox, Zuberbuhler, Park, Neches, Mathews and Zoltun11, Reference Yahalom, Jerushalmi and Roguin12 and premature contractionsReference Lenox, Zuberbuhler, Park, Neches, Mathews and Zoltun11, Reference Woo13 have been reported in children with acute rheumatic fever. All these abnormalities were defined based on 12-lead standard electrocardiography. However, the real prevalence of these abnormalities has not been investigated previously by evaluating long-term electrocardiographic recordings. In this study, we evaluated the asymptomatic rhythm and atrioventricular conduction abnormalities in children with the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever using the 24-hour electrocardiography.

Materials and methods

The study was performed between June, 2005 and July, 2008. Seventy-two consecutive children, who were diagnosed as having acute rheumatic fever, comprised the study population.

Diagnosis

The first attack of acute rheumatic fever was diagnosed strictly on the basis of Jones criteria.14–16 Patients with a recurrence of acute rheumatic fever were also included in the study, and the diagnosis of recurrences was made on the basis of the recommendations of the American Heart Association.14 The patients were grouped in terms of the major criteria present in each group. Subclinical carditis was not accepted as a major finding.Reference Ferrieri17

Analysis of rhythm and conduction abnormalities

PR and corrected QT intervals were measured from the standard electrocardiography obtained on admission. The measurements were made on three consecutive beats from DII manually, and the mean values were used. Standard electrocardiography was also evaluated in terms of additional abnormalities. Following the diagnosis, 24-hour electrocardiography was started (DMS 300-7 Holter recorder, DMS Inc., New York, United States of America), and the recordings were evaluated the following day (DMS Cardioscan 11 Holter analysis program, DMS Inc., New York, United States of America). The recordings were evaluated by 1-minute strips, and the abnormal beats and rhythms were identified. PR interval at the minimum and maximum heart rate strips was measured – measurements were made on four consecutive beats, and the average was used – and the number of pauses ⩾2.5 seconds, if present, was recorded.

The rhythm and conduction abnormalities were identified using the criteria defined hereunder:

• Prolonged PR interval was defined as a PR interval longer than the upper limit of normal for age and heart rate.Reference Park and Guntheroth18

• Second- and third-degree atrioventricular block were identified according to previously defined criteria.Reference Park and Guntheroth18, Reference El-Sherif, Aranda, Befeler and Lazzara19

• Corrected QT was measured using Bazett’sReference Bazett21 formula. A corrected QT interval ⩾0.44 second was accepted as prolonged.Reference Dickinson20

• Supraventricular and ventricular premature contractions were identified by previously defined criteria.Reference Park and Guntheroth18 Premature contractions were qualified as rare if the total number was <60 beats per hour, and frequent if >60 beats per hour.Reference Carboni and Garson22

• Accelerated junctional rhythm was defined as a narrow QRS rhythm when the ventricular rate was the same or exceeded the atrial rate. Atrioventricular dissociation was considered to be present when the atria and the ventricles operated independently for more than three beats.Reference Cristal, Stern and Gueron23

• Junctional escape beat and rhythm were defined as the presence of a junctional beat or several beats following a pause after a normal sinus beat.

• Ectopic atrial rhythm was defined if p-wave polarity clearly changed during sinus rhythm.

Exclusion criteria

The patients who did not fulfill the Jones criteria and those in whom 24-hour electrocardiography could not be performed for technical reasons were excluded from the study.

Statistical analysis

The data were transferred to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences pocket program. In order to investigate the relations of clinical findings with rhythm and conduction abnormalities, the following tests were used:

• Pearson χ2 analysis for comparison of frequencies of electrocardiography findings.

• Pearson correlation analysis for investigation of the correlation between different electrocardiography intervals.

• Spearman bivariate correlation analysis for investigation of the correlation between the frequencies of rhythm and conduction abnormalities and the laboratory results anti-streptolysin-O, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

• Student’s t-test (Mann–Whitney U test) for comparison of mean values.

• A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

The 72 consecutive patients with acute rheumatic fever formed the study group. Eight patients were excluded (four due to lack of 24-hour electrocardiography and four for failure to meet diagnostic criteria). The remaining 64 patients were included in the evaluation.

The mean age of the patients was 11.8 years, at a median of 12 years, with a range from 4 to 12 years. The mean weight was 37.6 kilograms, with a range from 15 to 84 kilograms. Thirty-seven of the patients were female, and the female/male ratio was 1:0.72.

Of the patients, 61 (95.3%) were evaluated during the first attack and 3 (4.7%) during recurrence.

Mean anti-streptolysin-O value was 995.9 International Units per litre with a range from 51 to 3360 International Units per litre, median 967.5 International Units per litre. Only one patient had a low anti-streptolysin-O value (<200 International Units per litre).

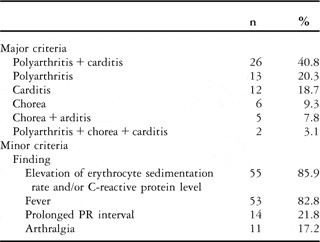

The frequencies of the major and minor criteria are given in Table 1.

Table 1 The frequency of major and minor criteria during diagnosis.

Carditis was diagnosed in 45 (70.3%) patients, either isolated or together with the other findings. In 42 of them (93.4%), it was mild; in one (2.2%), it was moderate; and in two (4.4%) patients, carditis was severe. Mitral regurgitation was detected in 38 (84.5%) and aortic regurgitation in seven (15.5%) patients.

The mean erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 81.4 millimetres per hour with a range from 6 to 125 millimetres per hour, median 90.5 millimetres per hour. Mean serum C-reactive protein level was 8.73 milligram per decilitre with a range from range 0.3 to 33.4 milligrams per decilitre, median 6.8 milligram per decilitre.

All patients had a 12-lead standard electrocardiography and the mean 24-hour electrocardiography time was 1227.8 minutes with a range from 770 to 1438 minutes, median 1270 minutes.

Rhythm and conduction abnormalities

Heart rate variables

The mean heart rate on standard electrocardiography was 106 beats per minute with a range from 75 to 180 beats per minute, median 107 beats per minute. The means of average, minimum and maximum heart rates on 24-hour electrocardiography are given in Table 2.

Table 2 Heart rate variables measured from 24-hour electrocardiography.

Atrioventricular conduction

The mean PR interval on standard electrocardiography was measured as 0.15 second with a range from 0.10 to 0.24 second, median 0.14 second. It was 0.14 second in patients with carditis and 0.15 second in patients without carditis, and the difference between the two groups was not statistically different (p > 0.05).

The PR interval was prolonged in 14 patients (21.9%), at the upper limit of normal in four patients (6.3%), and within normal limits in 46 patients (71.8%). In 10 patients with carditis (22.2%) and four patients without carditis (21.5%), the PR interval was prolonged, and the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Differences in PR interval among patients with different major manifestations were also not statistically significant (χ 2 = 0.011, p = 0.918).

The mean PR intervals at minimum and maximum heart rates on 24-hour electrocardiography were 137.8 and 113 milliseconds, respectively. On minimum and/or maximum heart rates, the PR interval was prolonged in 7 of 14 patients (50%) with a prolonged PR interval on standard electrocardiography. The PR interval on minimum and/or maximum heart rates was also prolonged in 3 of 50 patients (6%) with a normal PR interval on standard electrocardiography.

Although no advanced-degree atrioventricular block was observed on standard electrocardiography, Mobitz type I block and atypical Wenckebach periodicity simulating Mobitz II block (Fig 1) were determined in one patient on 24-hour electrocardiography.

Figure 1 Mobitz type I block and Wenckebach periodicity are seen on Holter recording.

Accelerated junctional rhythm

Accelerated junctional rhythm was determined in three standard electrocardiographies (4.7%). In two of them, junctional rhythm was present in the whole record (Fig 2), and in one it continued for three to five beats (Fig 3). Atrioventricular dissociation was present in two of three beats (Fig 4).

Figure 2 Sustained accelerated junctional rhythm without atrioventricular dissociation in the surface electrocardiography (patient 19).

Figure 3 Non-sustained accelerated junctional rhythm with atrioventricular dissociation in the surface electrocardiography (patient 26).

Figure 4 Non-sustained junctional rhythm episodes with atrioventricular dissociation are seen. Junctional rhythm becomes apparent when the sinus rhythm decreases.

None of the patients with carditis had a junctional rhythm on standard electrocardiography. In contrast, 3 of 19 (15.8%) patients without carditis had junctional rhythm, and the relationship between the absence of carditis and the presence of accelerated junctional rhythm on standard electrocardiography was significant (χ 2 = 7.455, p = 0.006).

No relationship was determined between the presence of accelerated junctional rhythm and prolonged PR on standard electrocardiography (χ 2 = 0.242, p = 0.623). No correlation was determined between the presence of accelerated junctional rhythm and serum levels of anti-streptolysin-O and C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (p > 0.05).

On 24-hour electrocardiography, accelerated junctional rhythm was present in nine (14%) patients. The rhythm characteristics of the accelerated junctional rhythm in these patients are given in Table 3.

Table 3 The rhythm characteristics of the accelerated junctional rhythm detected on 24-hour electrocardiography.

*See Fig 4

Only two of these nine patients had an accelerated junctional rhythm on standard electrocardiography (patients 26 and 56). Thus, accelerated junctional rhythm on standard electrocardiography and/or 24-hour electrocardiography was detected in a total of 10 (15.6%) patients.

Accelerated junctional rhythm was detected in electrocardiography and/or 24-hour electrocardiography in 4 of 45 patients (8.9%) with carditis and 6 of 19 patients (31.6%) without carditis, and the difference between prevalences was significant (χ 2 = 5.217, p = 0.022).

No relationship was detected between accelerated junctional rhythm on standard electrocardiography and/or 24-hour electrocardiography and prolonged PR on standard electrocardiography (χ 2 = 0.024, p = 0826).

No correlation was detected between accelerated junctional rhythm on standard electrocardiography and/or 24-hour electrocardiography and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or serum levels of anti-streptolysin-O and C-reactive protein (p > 0.05).

Premature contractions

On standard electrocardiography, only one patient (1.7%) had single ventricular premature contractions, whereas 19 patients (29.7%) had supraventricular premature contractions and/or ventricular premature contractions in 24-hour electrocardiography. Isolated supraventricular premature contractions were detected in 10 patients, isolated ventricular premature contractions in four patients, and both supraventricular premature contractions and ventricular premature contractions in five patients.

In 1 of 15 patients, supraventricular premature contractions were frequent, and in one patient with infrequent supraventricular premature contractions, a non-sustained supraventricular run was present (Fig 5).

Figure 5 The non-sustained supraventricular run on the Holter recording of the patient with severe carditis.

Ventricular premature contractions were infrequent in all patients. In one of nine patients with ventricular premature contractions, ventricular couplets (Fig 6) were present, and in one patient, ventricular premature contractions were multiform. No ventricular runs were detected.

Figure 6 Ventricular couplets on the Holter recording of a patient with infrequent ventricular premature contractions.

In three patients with premature contractions, associated rhythm disturbances were detected: junctional escape beats (n = 1), accelerated junctional rhythm (n = 1), and ectopic atrial rhythm (n = 1).

In 17 of 45 patients (37.8%) with carditis, no type of PC was present, and only 2 of 19 patients (10.5%) without carditis had premature contractions. A significant relationship between the presence of carditis and PCs (χ 2 = 4.753, p = 0.029) was detected.

No relationship between the presence of premature contractions and prolonged PR interval on standard electrocardiography (χ 2 = 0.586, p = 0.444) was detected. There was also no correlation between the presence of premature contractions and anti-streptolysin-O, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate levels (p > 0.05).

Corrected QT interval

On standard electrocardiography, the mean corrected QT interval was measured as 405 milliseconds with a range from 333 to 499 milliseconds, median 405 milliseconds. It was 401 milliseconds in patients with carditis and 414 milliseconds in patients without carditis, and the difference between the groups was not significant (p > 0.05).

In four patients (6.3%), the corrected QT interval was longer than 440 milliseconds; only one of them had carditis. There was a significant relationship between the presence of prolonged corrected QT interval and the absence of carditis (χ 2 = 4.197, p = 0.041).

Three of four patients with a prolonged corrected QT interval on standard electrocardiography also had a prolonged PR interval. A significant relationship was detected between the presence of prolonged PR and corrected QT intervals (χ 2 = 7.046, p = 0.008). A positive correlation was also detected between PR and corrected QT intervals on standard electrocardiography (p = 0.000).

No correlation was detected between anti-streptolysin-O, C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate levels and the presence of the prolonged corrected QT interval (p > 0.05).

Other findings

In two patients (3.1%), sinus arrests followed by pauses shorter than 1.5 seconds and junctional escape beat (n = 1) or junctional escape rhythm (n = 1) were detected. In these patients, the duration of the longest pauses were 1289 and 969 milliseconds. A pause of >1.5 seconds (1515 milliseconds) was detected in only one patient during sinus rhythm. In two patients (3.1%), sustained ectopic atrial rhythm episodes on 24-hour electrocardiography and in one patient negative T waves on standard electrocardiography were detected.

Discussion

There is no specific clinical or laboratory test for the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever, and Jones criteria are used for a correct diagnosis.14 In the presence of evidence of recent streptococcal infection, two major criteria or one major and two minor criteria indicate acute rheumatic fever.14 The frequency of major findings differs in the literature. Carditis is seen in about 30–70%, polyarthritis in 40–70%, chorea in 10–30%, erythema marginatum in 0.5–4% and subcutaneous nodules in 0–10% of the cases.Reference Tani24 No erythema marginatum and subcutaneous nodules were seen among our patients. The frequency of the major findings was as follows: polyarthritis + carditis 40.8%, polyarthritis 20.3%, carditis 18.7%, chorea 9.3%, chorea + carditis 7.8%, and polyarthritis + chorea + carditis 3.1%. Thus, carditis was present in 70.3%, arthritis in 64%, and chorea in 20.3% of the patients.

PR prolongation in many acute rheumatic fever patients has been a well-known finding since 1920.Reference Clarke and Keith25, Reference Hoffman, Rhodes, Pyles, Balian, Neal and Einzig26 Over time, many other rhythm and conduction abnormalities were defined in children with acute rheumatic fever. Second-degree atrioventricular block,Reference Stocker, Czoniczer, Massell and Nadas2, Reference Zalzstein, Maor, Zucker and Katz4 complete heart block,Reference Stocker, Czoniczer, Massell and Nadas2–Reference Malik, Hassan and Khan7 junctional tachycardia with or without atrioventricular dissociation,Reference Cristal, Stern and Gueron8, Reference Olgun and Ceviz9 ventricular tachycardia,Reference Olgun and Ceviz9, Reference Freed, Sacks and Ellman10 right-left bundle branch block,Reference Lenox, Zuberbuhler, Park, Neches, Mathews and Zoltun11, Reference Yahalom, Jerushalmi and Roguin12 bradytachycardia, and ventricular premature beatsReference Lenox, Zuberbuhler, Park, Neches, Mathews and Zoltun11, Reference Woo13 were also reported. These findings were primarily reported as case reports, and as case series in a few papers.Reference Zalzstein, Maor, Zucker and Katz4, Reference Cristal, Stern and Gueron8, Reference Clarke and Keith25 In each series, only one pathology had been investigated and the problem was defined based on the standard electrocardiography obtained at admission, even though cardiac rhythm is an ongoing process and changes substantially.Reference Clarke and Keith25 Electrocardiography on a 24-hour basis is a valuable technique for the evaluation of changes in cardiac rhythm and conduction.Reference Ayabakan, Özer, Çeliker and Özme27 A review of the literature in PubMed revealed no previous study evaluating the cardiac rhythm and conduction abnormalities in children with acute rheumatic fever using 24-hour electrocardiography. Our study is the first to investigate this subject and the relationship between these abnormalities and the clinical findings of the patients.

Atrioventricular conduction

The impulse originates within the sinus node, activates atrial myocardium, and reaches the atrioventricular node. The fibres of the atrioventricular node, located near the annulus of the tricuspid valve, converge into a compact bundle, the bundle of His, which penetrates the cardiac fibrous skeleton and gives off fibres to the right and left ventricles. The bundle of His normally constitutes the only electrical connection between the atrial and ventricular chambers. From the atrioventricular node through the bundle of His and before arborisation of the right and left bundle branches, the conduction system is encased in the connective tissue strome and has no connection with the myocardium.Reference Kearney and Titus28

Deceleration in atrioventricular conduction results in atrioventricular block. In patients with acute rheumatic fever, prolonged PR interval (first-degree heart block) is used as a minor diagnostic criterion.14 It has been shown that atropine reverses the PR interval prolongation in patients with acute rheumatic fever.Reference Clarke and Keith25 The effect of atropine is to block the vagal receptors in the heart. The principle of these receptors is in the sinoatrial and atrioventricular node. It is not known whether these conduction changes are mediated by acetylcholine-like substances or by direct vagal action.

On the basis of their observations in patients with acute rheumatic fever, Clarke and KeithReference Clarke and Keith25 concluded that the rheumatic affection of atrioventricular conduction is proximal to the trifascicular system. However, the exact mechanism by which the rheumatic process causes this vagal effect is not known. Although an antigenic mimicry had been shown between the cardiac valve glycoprotein and the carbohydrate antigens of group A β-haemolytic streptococcus, to date no such relationship with the glycoproteins of conduction tissue has been described.Reference Tani24, Reference Clarke and Keith25, Reference Dajani29, Reference Stollerman30, Reference Zalzstein, Maor, Zucker and Katz31 Furthermore, the atrioventricular node has a very low content of glycoprotein compared with the peripheral conducting system.Reference Clarke and Keith25

First-degree heart block is seen in about 10–75% of children with acute phase ARF,Reference Cristal, Stern and Gueron23, Reference Clarke and Keith25, Reference Zalzstein, Maor, Zucker and Katz31, Reference Rayamajhi, Sharma and Shakya32 and it is not related to the presence of carditis.Reference Clarke and Keith25 In addition to the first-degree block, advanced atrioventricular block can also occur. In the literature, second- and third-degree atrioventricular block had been reported mostly in case reports.Reference Stocker, Czoniczer, Massell and Nadas2–Reference Malik, Hassan and Khan7, Reference Olgun and Ceviz9, Reference Lenox, Zuberbuhler, Park, Neches, Mathews and Zoltun11, Reference Kula, Olguntürk and Özdemir33 Zalzstein et alReference Zalzstein, Maor, Zucker and Katz31 reported one Mobitz type I (1.5%) and three (4.6%) complete heart block cases among 65 patients with acute rheumatic fever. Among 508 children with acute rheumatic fever, Clark and KeithReference Clarke and Keith25 reported 12 (2.36%) cases with Mobitz type I block, and three (0.59%) cases with complete heart block. Mobitz type II block had never been reported in children with acute rheumatic fever. In our study, the frequency of first-degree heart block was 21.9% (14/64). No Mobitz type II or complete heart block was observed on standard electrocardiography among our patients. The mean PR interval was not statistically different between patients with and without carditis. Furthermore, no relation was detected between the presence of first-degree heart block and the types of major findings and association of carditis. These findings support the previously mentioned observation that the PR prolongation is not a part of carditis.

In half of the patients with first-degree heart block on standard electrocardiography (7/14), the PR interval during the minimum and/or the maximum heart rate on 24-hour electrocardiography was normal. In addition, in three patients, the PR interval was normal on standard electrocardiography (3/50, 6%), but was prolonged during the minimum and/or maximum heart rate on 24-hour electrocardiography. In one patient, we observed Mobitz type I block with atypical Wenckebach periodicity simulating a Mobitz II atrioventricular block (Fig 1). This patient is the first with acute rheumatic fever in whom atypical Wenckebach periodicity has been defined. Mobitz type II and complete heart block were also not observed on 24-hour electrocardiography. These findings indicate that the PR interval has an important diurnal variation; thus, in patients with acute rheumatic fever with normal PR interval on standard electrocardiography, it may be useful to investigate the PR interval on 24-hour electrocardiography. This will also make it possible to determine the more advanced heart block periods during the remaining hours of the day, as in one patient (patient 28) in our study.

Accelerated junctional rhythm

An original arrhythmia reported in patients with acute rheumatic fever is the junctional acceleration. In previous years, its forms with atrioventricular dissociation were defined and had been accepted as a manifestation of carditis.Reference Cristal, Stern and Gueron23, Reference Goodman and Pick34 However, atrioventricular dissociation does not accompany junctional acceleration in all cases. The most common cause of atrioventricular dissociation in acute rheumatic fever is the non-paroxysmal atrioventricular nodal tachycardia. It has the same clinical connotations with regard to the involvement of the myocardium, especially the atrioventricular node, by the underlying rheumatic disease as does a prolongation of the atrioventricular conduction time.Reference Goodman and Pick34 It is not known whether or not there is an association between these two functional disorders. It has been observed that the atrioventricular dissociation appears with the deceleration of the sinus rhythm, and suddenly disappears with the acceleration of the sinus rhythm. Thus, it may be speculated that the vagal effect resulting in PR prolongation may be related to the occurrence of an accelerated junctional rhythm in patients with acute rheumatic fever. However, in our study, no statistical relationship was determined between the presence of accelerated junctional rhythm and PR prolongation (p > 0.05). There was also no correlation between the presence of accelerated junctional rhythm and the duration of the PR interval on standard electrocardiography (p > 0.05). This finding may suggest that these two disorders are results of different underlying mechanisms.

The first comprehensive study investigating the atrioventricular dissociation in patients with acute rheumatic fever was carried out by Cristal et alReference Cristal, Stern and Gueron23. In that study, atrioventricular dissociation was determined in 14 of 70 (20%) standard electrocardiographies, Although the mechanism could not be clarified, it was considered to be the result of enhanced atrioventricular nodal activity. In patients without carditis, atrioventricular dissociation was seen more frequently, and PR prolongation was present in only a minority of these patients.Reference Cristal, Stern and Gueron23 Clarke and KeithReference Clarke and Keith25 determined atrioventricular junctional rhythm in only 9.4% (48 patients) of standard electrocardiographies of 508 patients with acute rheumatic fever. It was not related to the presence of carditis, and atrioventricular dissociation was present in 35 of 48 electrocardiographies.

In this study, junctional rhythm was present in only 4.7% (3/64) of the standard electrocardiography. However, it was determined in nine (14%) patients in 24-hour electrocardiography (Table 3). Overall, the frequency of the accelerated junctional rhythm was 15.6% (10/64). This result indicates that the true frequency of the accelerated junctional rhythm is higher than that of the frequencies derived from standard electrocardiography. In addition, this is the first study confirming the statistical relationship (p < 0.05) between the presence of accelerated junctional rhythm and the absence of carditis. The heart rate was between 51 and 111 beats per minute, and atrioventricular dissociation was present in half of the patients. These results were compatible with previous reports.Reference Cristal, Stern and Gueron23, Reference Clarke and Keith25 Increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate and serum C-reactive protein levels are being used as indicators of the severity of the inflammation. There was no correlation between the inflammation marker levels and the presence of accelerated junctional rhythm on standard electrocardiography and/or 24-hour electrocardiography. This finding suggests that accelerated junctional rhythm in patients with acute rheumatic fever is not a result of the severity of inflammation.

Premature contractions

Although the supraventricular premature contractions and ventricular premature contractions frequently occur in patients with inflamed myocardium or after cardiac surgery, they can also be observed in normal healthy children. There has been no previous study investigating the frequency and importance of premature contractions in patients with acute rheumatic fever. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report that has evaluated this subject.

In a study investigating the frequency of premature contractions in a population of 10 to 13-year-old healthy children, ventricular premature contractions were observed in 26% and supraventricular premature contractions in 13% of 24-hour electrocardiography, and in all cases the premature contractions were infrequent.Reference Saraiva, Santos and de Aguiar35 In our study, the frequency of premature contractions – supraventricular premature contractions and/or ventricular premature contractions – was 1.7% on standard electrocardiography and 29.7% on 24-hour electrocardiography. Although this ratio is close to the frequency seen in normal children, the presence of premature contractions was significantly related to the presence of carditis (p = 0.029). The presence of non-sustained supraventricular tachycardia, multiple ventricular couplets, and multiform ventricular premature contractions also makes this relationship stronger. Although the presence of premature contractions was related to carditis, it was not correlated with the severity of inflammation. New studies comparing the frequency of premature contractions during and after the acute phase of the disease are needed to draw a conclusion about the real relationship with carditis and premature contractions.

Corrected QT interval

Although prolongation of the QT interval has been reported since 1949,Reference Scott, Williams and Fiddler36 the torsade de pointes has been reported in only one patient with acute rheumatic fever.Reference Liberman, Hordof, Alfayyadh, Salafia and Pass37 Polat et alReference Reddy, Chun and Yamamoto3 compared the QT and corrected QT dispersions between patients with acute rheumatic fever with and without carditis, and found increased dispersion values in patients with carditis.Reference Cristal, Stern and Gueron8 The QT and corrected QT dispersions were reported to be normalised after treatment. On the basis of this finding, the authors offered increased QT and corrected QT dispersions as indicators of carditis. In this study, we did not evaluate the dispersions. In contrast to previous studies, we did not find a significant difference between the mean corrected QT values of patients with and without carditis.

There was a significant correlation between the PR and corrected QT intervals on standard electrocardiography (χ 2 = 0.0446, p = 0.000) in our study. This finding suggests that the same mechanism or different electrophysiological injuries occurring at the same time affect both the atrioventricular conduction and cardiac repolarisation.

Other findings

The frequencies of sinus arrest and junctional escape rhythm (3.1%) and intermittent ectopic atrial rhythm (3.1%) were very low. These abnormalities can also be seen in normal children; therefore we doubt that they have a specific value for acute rheumatic fever.Reference Dickinson39, Reference David40

Conclusion

Our results indicate that in children with acute rheumatic fever, the frequency of rhythm and conduction abnormalities is higher than reported on the basis of standard electrocardiography recordings; 24-hour electrocardiography makes it possible to detect the abnormalities that do not appear on standard electrocardiography. Further studies are needed to detect whether or not these arrhythmias are specific to acute rheumatic fever; life-threatening arrhythmias are not frequent in acute rheumatic fever.

Study limitations

• Although this study provides important information about the frequency of asymptomatic rhythm and conduction abnormalities in children with acute rheumatic fever, it does not clarify whether or not these arrhythmias are specific to the disease. The specificity of these abnormalities should be evaluated in future investigations of the same abnormalities in children with the other systemic diseases affecting joints and the heart and in normal children.

• The 24-hour electrocardiography should be re-evaluated after the acute phase in order to determine whether or not these abnormalities are related to the acute phase of the disease.

• Carditis can occur without audible evidence of valvar damage, but, still it is debatable whether the subclinic carditis should be accepted as a major criterion or not. Although the members of the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease of the American Heart Association conclude that Doppler echocardiographic findings alone should not be classified as either a major or minor Jones criteria in the guidelines for the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever at this time,Reference Ferrieri17 some studies support the use of Doppler echocardiography in the detection of rheumatic carditis.Reference Minich, Tani, Pagotto, Shaddy and Veasy41–Reference Vijayalakshmi, Vishnuprabhu, Chitra, Rajasri and Anuradha43 Subclinical carditis is not accepted as a major criterion in this study. Therefore, some patients were classified as having solely polyarthritis or chorea. Our statistical results might have been affected by this classification. Further studies, investigating the relationship between the described asymptomatic rhythm and conduction abnormalities and sublinical carditis, may provide additional support for the usefulness of echocardiography in the evaluation of cardiac involvement in ARF patients.