Accelerated idioventricular rhythm is a benign but rare form of ventricular tachycardia that does not require treatment in the great majority of cases.

When presenting in the neonatal period, AIVR is usually diagnosed in a healthy child being monitored for another reason.Reference Crosson, Callans and Bradley1 AIVR is characterised by the presence of a wide complex tachycardia, usually with rates around 10% faster than sinus rhythm in an asymptomatic, otherwise well patient.Reference Crosson, Callans and Bradley1–Reference Sekarski, Meijboom, Di Bernardo, Ksontini and Mivelaz8 In addition to this, AIVR may be associated with atrioventricular dissociation and fusion beats.Reference Reynolds and Pickoff3,Reference Rehsia, Pepelassis and Buffo-Sequeira4

Case report

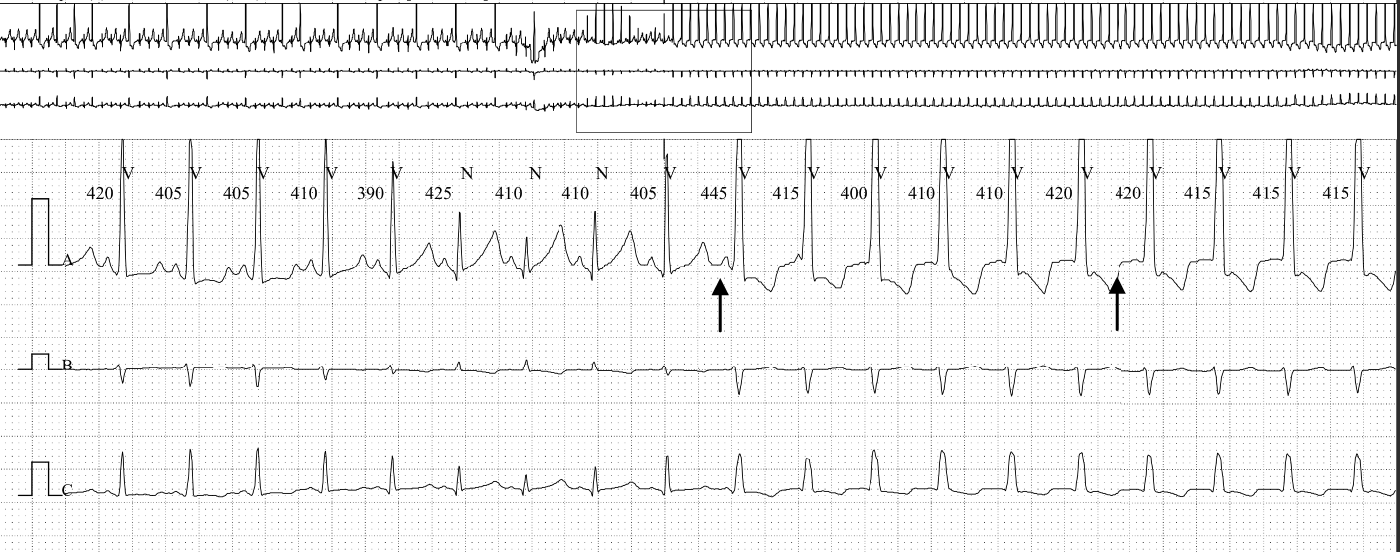

We present the case of a 25-day-old newborn, born at full-term after an uneventful pregnancy. Parents were non-consanguineous and family history was irrelevant. He presented to the emergency department due to a head injury, after he had fallen from his mother’s arms. The head CT showed a small subdural haematoma and he was admitted to an intermediate care unit for monitoring over a 24-hour period. During this time, the ECG monitoring was arrhythmic, but the baby was clinically well and haemodynamically stable. His ECG revealed a broad complex tachycardia with a rate of around 150 beats per minute, atrioventricular dissociation, and left bundle branch block alternating with a sinus rhythm of about 140 beats per minute. A diagnosis of AIRV was made. Afterwards, a 24-hour ECG monitoring was performed, which confirmed this diagnosis (Fig 1). Additionally, this exam revealed a prolonged corrected QT interval. Echocardiogram showed no structural abnormalities and preserved cardiac function. Since there were no other criteria for long QT syndrome (no symptoms, no bradycardia, no T wave alternans, no family history of sudden death or long QT syndrome), no specific treatment was started and he was discharged to the outpatient clinic.

Figure 1. Rhythm strip showing accelerated idioventricular rhythm. The arrows point to the p waves which demonstrate the atrioventricular dissociation. The first complex after the first arrow is also a fusion beat. The Qtc is prolonged (489 m/seconds, Bazett).Reference Schwartz and Ackerman9

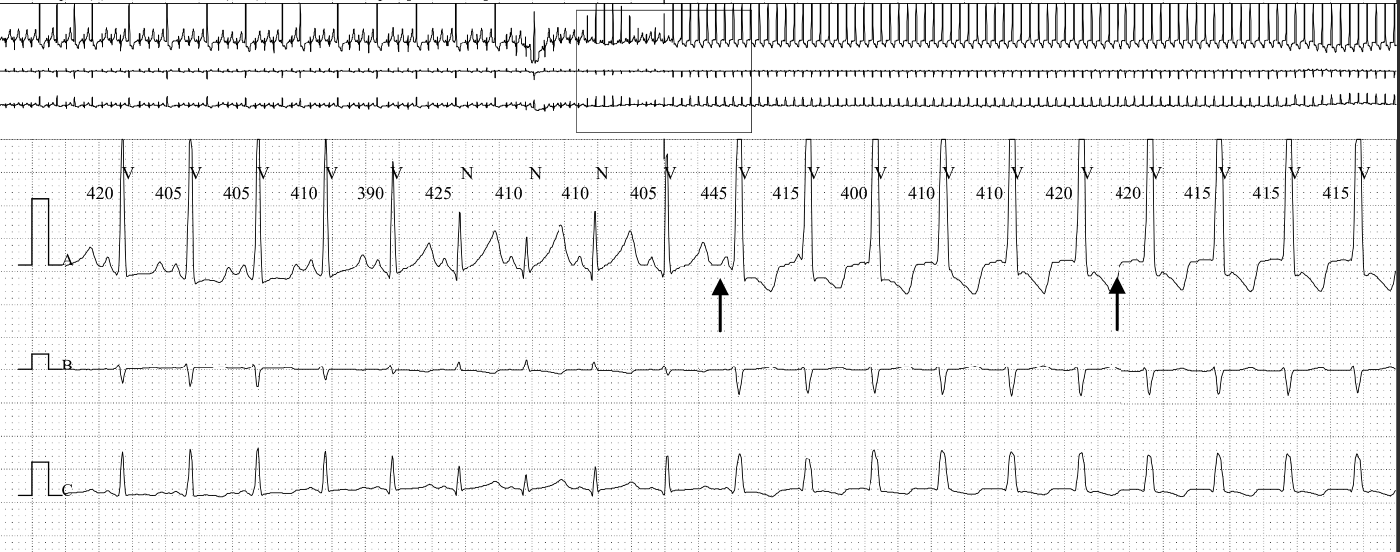

At 2 months of age, the follow-up ECG showed sinus rhythm and QTc within the normal range for his age (404 m/seconds). The 24-hour monitoring at the time was normal, apart from borderline QTc (Fig 2). Currently, at 6 months follow–up, he remains asymptomatic in sinus rhythm with normal QTc.

Figure 2. Rhythm strip of the same patient, performed at 2 months of age, now in sinus rhythm. The Qtc interval is borderline (462 m/seconds, Bazett).Reference Schwartz and Ackerman9

Conclusion

Differentiating AIVR from ventricular tachycardia may be somewhat challenging, but there are a few clinical features to help distinguish the two: in AIVR, the diagnosis is usually made by chance in a haemodynamically stable, asymptomatic child, while in VT, the child is usually unwell and unstable. Furthermore, AIVR typically converts to sinus rhythm with exertion, while VT does not.Reference Reynolds and Pickoff3 Additionally, AIVR usually presents with small, intermittent tachycardia bursts while VT tends to present with long runs.Reference Reynolds and Pickoff3–Reference Anatoliotaki, Papagiannis, Stefanaki, Koropouli and Tsilimigaki5

Even though the echocardiogram is usually normal, this tachycardia can also be associated with CHD, although it does not seem to change the clinical outcomes in such cases.Reference Freire and Dubrow6 This arrhythmia is self-limited, benign, never degenerating into VT,Reference Sekarski, Meijboom, Di Bernardo, Ksontini and Mivelaz8 and resolving within the first year of life, with no treatment being recommended in the paediatric population.Reference Crosson, Callans and Bradley1,Reference Rehsia, Pepelassis and Buffo-Sequeira4–Reference Sekarski, Meijboom, Di Bernardo, Ksontini and Mivelaz8

Congenital long QT syndrome is very rare in the neonatal period, but it is an important cause of sudden cardiac death in the first year of life and should be ruled out.Reference Schwartz and Ackerman9,Reference Schwartz, Garson and Paul10

In the case presented above, the prolonged QT interval was an isolated finding, as there were no other features of LQTS in his personal or family history, nor in the ECG monitoring.

In summary, in the neonatal period, AIVR is benign and self-limited. Although differential diagnosis with VT might be challenging in some cases, in the presence of a clinically well, stable child, careful follow-up is sufficient and no treatment is recommended. Additionally, LQTS is a worrisome entity and should be carefully excluded, especially in the neonatal period.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The author assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation (please name) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and has been approved by the institutional committee (Comissão de Ética - Hospital de Santa Cruz, CHLO).