Background

An absent ductus venosus is a rare vascular abnormality of unknown aetiology with an estimated prevalence of about 1 in 2500 early pregnancy ultrasounds. Reference Staboulidou, Pereira, De Jesus Cruz, Syngelaki and Nicolaides1 Current absent ductus venosus reports comprise a variety of umbilical vein connections including to the portal sinus, right atrium, coronary sinus, inferior vena cava, and iliac veins. Reference Acherman, Evans and Galindo2,Reference Pacheco, Brandão, Montenegro and Matias3 Prognosis of an absent ductus venosus varies from uncomplicated to foetal demise, which is influenced by the degree of heart failure and the presence of chromosomal, cardiac, and extracardiac abnormalities. Reference Staboulidou, Pereira, De Jesus Cruz, Syngelaki and Nicolaides1–Reference Maruotti, Saccone, Ciardulli, Mazzarelli, Berghella and Martinelli5 The degree of heart failure varies from mild cardiomegaly to foetal hydrops and may be related to the site of drainage and the presence or absence of venous pathway restriction. Reference Acherman, Evans and Galindo2–Reference Maruotti, Saccone, Ciardulli, Mazzarelli, Berghella and Martinelli5 After birth, umbilical venous drainage ceases and, in the absence of significant associated abnormalities, congestive heart failure improves with adequate management.

Case report

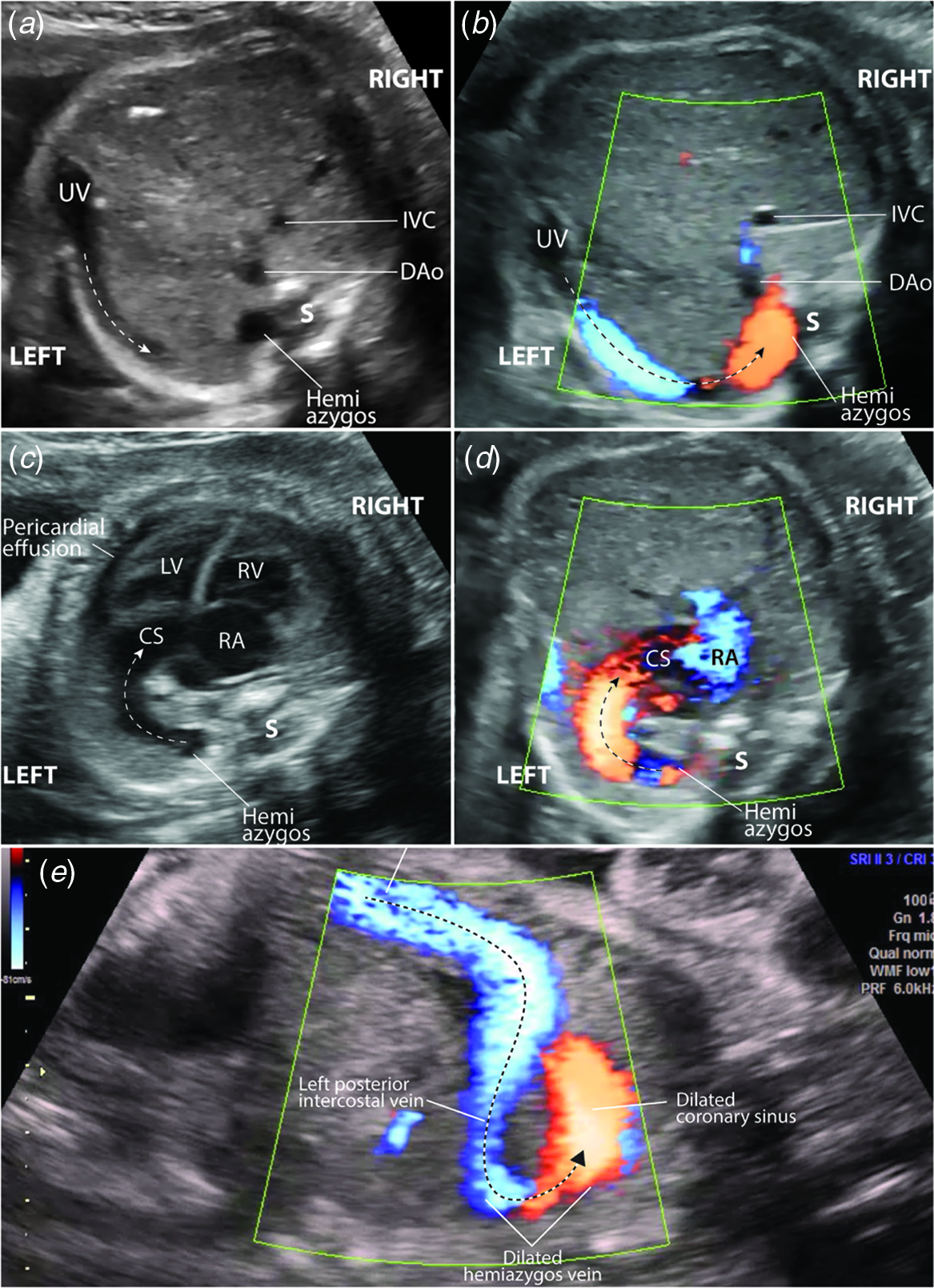

A 27-year-old pregnant woman at 27-week gestation was referred for a foetal cardiac evaluation because of cardiomegaly found on obstetric ultrasonography. The foetal echocardiogram demonstrated situs solitus, dextrocardia, absent ductus venosus with an unusual and unrestricted umbilical venous pathway. The umbilical venous flow drained into the left posterior intercostal vein and then into the hemiazygos vein. The hemiazygos vein was dilated for a short segment and subsequently drained into a very dilated coronary sinus (Fig 1a–d, and video clips 1 and 2). The unusual venous pathway showed unrestricted flow from the umbilical vein to the coronary sinus (Fig 1e, and video clips 1 and 2). There was cardiomegaly with a cardiothoracic ratio of 55% by area and a 4 mm circumferential pericardial effusion, the systolic function was qualitatively normal. Because of cardiomegaly and pericardial effusion, we administered a course of maternal steroids for foetal lung maturation and initiated plans for delivery at a neonatal cardiac centre. As cardiomegaly increased (up to 60% cardiothoracic area ratio), the pericardial effusion enlarged, and a non-reassuring foetal assessment developed, the foetus was delivered via caesarean section at 30-week gestation.

Figure 1. Foetal echocardiogram. ( a ) Transverse view of the foetal abdomen and ( b ) at the same level with colour Doppler showing the umbilical venous pathway into a left intercostal vein (broken arrows), and the dilated hemiazygos vein segment. ( c ) Transverse view at the level of the four-chamber view showing an arch (broken arrow) connecting the dilated hemiazygos vein to the very dilated CS. Note also the cardiomegaly and the cardiac apex pointing towards the right. ( d ) Colour Doppler of the flow from the dilated hemiazygos vein to the very dilated CS. ( e ) Sagittal view of the foetal abdomen and chest showing the unrestricted flow through the unusual pathway between the umbilical vein and the dilated coronary sinus (broken arrow). Note the dilated left posterior intercostal vein and hemiazygos vein segment. DAo=descending aorta; IVC=inferior vena cava; LV=left ventricle; RA=right atrium; RV=right ventricle; S=spine; UV=umbilical vein.

At delivery, the newborn was hypotonic, cyanotic, heart rate at 150 bpm, not crying, and Apgars were 5 at 1 mi and 6 at 5 min; there was no response to positive pressure ventilation via mask. The patient was stabilised after orotracheal intubation and was transferred to the newborn ICU. At arrival to the NICU, the patient required chest compressions for bradycardia at 40 bpm with good response. One dose of surfactant was administered. Physical exam in the NICU showed no obvious dysmorphic features, the oxygen saturation was 86% with a FiO2 of 100%. Arterial blood gases reported pH 7.14, PCO2 70 mmHg, PO2 33 mmHG, SO2 71.3%, HCO3 19.1, base excess 6.5, lactate 1.2. Umbilical arterial and venous lines were inserted and inotropic support with dobutamine was administered during the first hours of life.

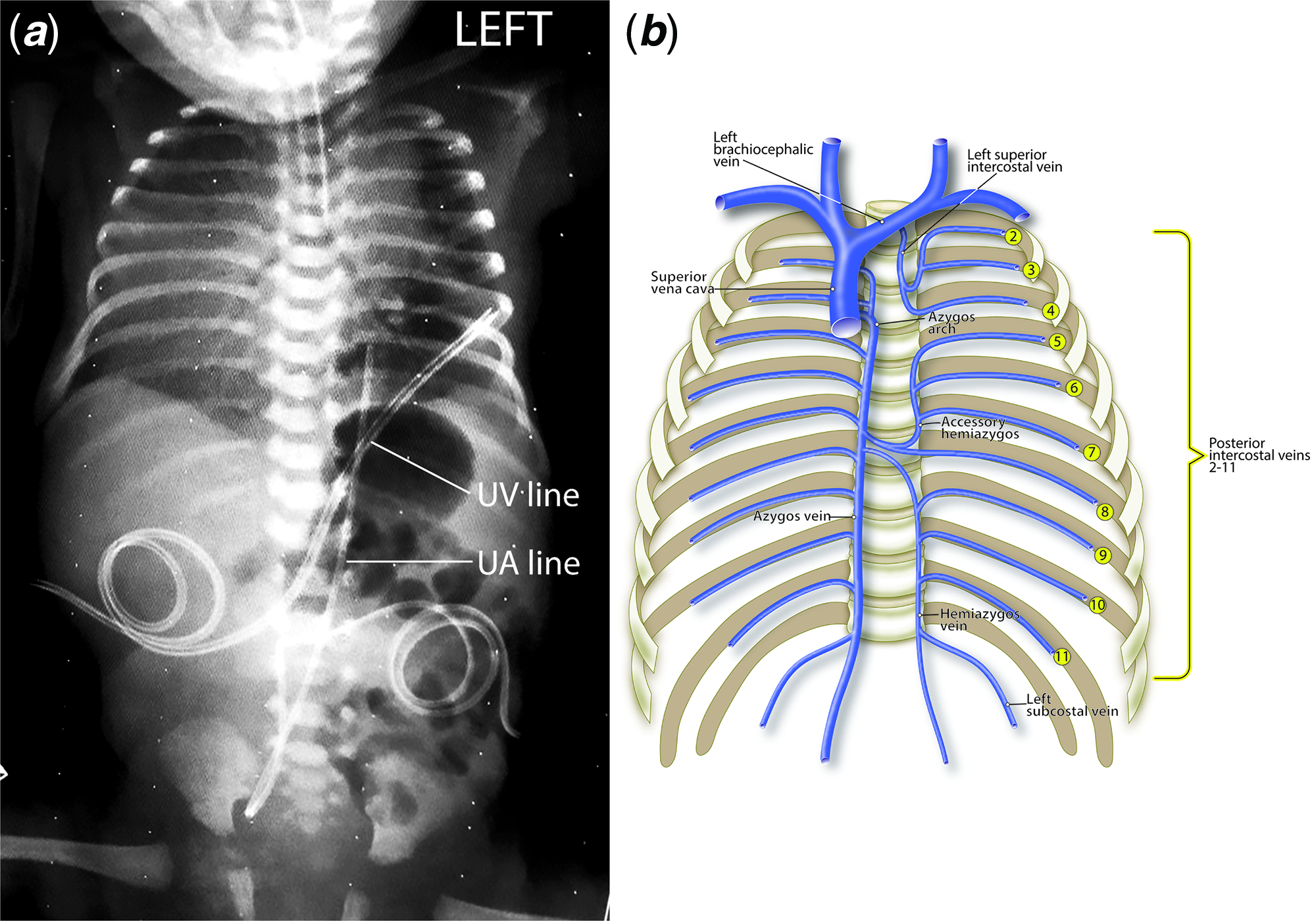

The initial chest X-ray demonstrated dextrocardia, cardiomegaly, and the umbilical venous line tip at the 6th left posterior intercostal space (Fig 2a). For additional clarification, Fig 2b illustrates the normal drainage of the left posterior intercostal veins to the hemiazygos system; it may help better visualise the unusual venous pathway, the dilatation of a segment of the hemiazygos vein, as shown in Figure 1, and the umbilical venous catheter pathway seen in the chest X-ray, as shown in Fig 2a.

Figure 2. ( a ) Chest and abdomen radiograph showing the dextrocardia and cardiomegaly, and the position of the UV and UA lines. Note the tip of the UV line at the 6th left rib. ( b ) Diagrammatic representation of the normal azygos and hemiazygos venous systems. Note the drainage of the left intercostal veins to the hemiazygos system.

The initial neonatal echocardiogram showed situs solitus, dextrocardia, normal left ventricular systolic function, right atrial and right ventricular enlargement, severe tricuspid valve regurgitation with suprasystemic pulmonary hypertension, bidirectional foramen ovale and ductus arteriosus shunting, and a dilated coronary sinus. There were no other cardiac or extracardiac abnormalities. The cerebral ultrasound was normal.

The patient showed progressive improvement with mechanical ventilation. An echocardiogram on the third day of life showed subsystemic pulmonary hypertension with only mild flattening of the ventricular septum, mild tricuspid valve regurgitation, and low velocity, mainly left-to-right shunt at the ductus. The patient was extubated and placed on nasal canula O2 at 1 week of age and was subsequently discharged home on supplemental oxygen at 3 weeks of age. The oxygen was discontinued at 1 month of age. The patient was doing well at the last follow-up at 3 months of age.

Discussion

Without a normal ductus venosus, the umbilical venous flow develops alternative pathways to the right atrium. Alternative pathways that lack flow restriction, a normal feature of the ductus venosus, may lead to foetal cardiac volume overload, foetal hydrops, and postnatal clinical compromise. Reference Staboulidou, Pereira, De Jesus Cruz, Syngelaki and Nicolaides1–Reference Maruotti, Saccone, Ciardulli, Mazzarelli, Berghella and Martinelli5 Table 1 summarises the sonographic and clinical data of 12 foetuses from previous publications with abnormal umbilical venous connection to the right atrium. Reference Acherman, Evans and Galindo2,Reference Sau, Sharland and Simpson6,Reference Perles, Nir, Nadjari, Ergaz, Raas-Rothschild and Rein7 Our case of an unusual unrestricted alternate pathway via the hemiazygos system led to significant prenatal and postnatal pathology. However, prompt caesarean section delivery in a neonatal cardiac centre resulted in an excellent outcome.

Table 1. Sonographic and clinical data of 12 foetuses with abnormal umbilical venous connection to the right atrium.

BW = birth weight; CD = caesarean delivery; CMV = cytomegalovirus; CS = coronary sinus; CT = cardiothoracic; GA = gestational age at first foetal echocardiogram; IUD = intrauterine death; IVC = inferior vena cava; PDA = patent ductus arteriosus; PS = portal sinus; RA = right atrium; UV = umbilical vein; and VSD = ventricular septal defect

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first absent ductus venosus report describing the illustrated, unusual umbilical venous pathway. It is important to detect such anomalies early to decide about the management and the prognosis of the foetus. After birth, umbilical venous drainage ceases and, in the absence of significant associated abnormalities, congestive heart failure improves with adequate management. The case underscores the need for comprehensive foetal cardiomegaly evaluation and the importance of prenatal diagnosis of significant cardiovascular malformations that, with prenatal planning, are best cared for in a centre with neonatal cardiology and intensive care services.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Drs William N. Evans and Ruben J. Acherman from the Children’s Heart Center in Las Vegas, Nevada for their critical review of the manuscript, illustrations, and valuable editorial comments.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that this work is exempt from Institutional Review Board for informed consent and approval.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951121002213.