Introduction

Collaborative mental health care services—which integrate mental health, primary care, and pertinent community supports—strive to ensure effective, comprehensive health care across an array of service users experiencing mental and other interrelated health issues (Graham, Reference Graham1998; Kates, Craven, Bishop, Clinton, Kraftcheck, Le Clair et al., 1997; Kates, Reference Kates2002; Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, 2006; Rockman, Salach, Gotlib, Cord, & Turner, Reference Rockman, Salach, Gotlib, Cord and Turner2004). As a result, collaborative mental health care has been identified as a best-practice model of service delivery for individuals with multifactorial health needs (Jeste, Gladsjo, Lindamer, & Lacro, Reference Jeste, Gladsjo, Lindamer and Lacro1996; Kates et al., Reference Kates, Craven, Bishop, Clinton, Kraftcheck and LeClair1997; Kates et al., 2002; Wolf, Starfield, & Anderson, Reference Wolf, Starfield and Anderson2002), including older adults. As older adults continue to age, they become increasingly susceptible to acquiring additional and chronic health conditions. In fact, the anticipated exponential growth in the number of older adults in Canada (Division of Aging and Seniors, 2002; Statistics Canada, 2005) is expected to result in a broad demographic of seniors acquiring concurrent, and chronic, mental and physical health conditions (Gilmour & Park, Reference Gilmour and Park2006; Jeste et al., Reference Jeste, Gladsjo, Lindamer and Lacro1996). An essential goal of current health care planning, therefore, is to ensure effective management of the complex health care needs of older adults through collaborative processes (Mirolla, Reference Mirolla2004).

An oft-unheeded factor affecting service delivery for older adults is the difficulty they face in accessing available supports (Bartels, Reference Bartels2004; Donnelly, Le Clair, Hinton, Horgan, Kreiger-Frost, MacCourt, 2006). Ultimately, without strategic planning to address these issues, the potential of collaborative models to address the health concerns of this vulnerable population may fail to be realized.

This article reports on a national consensus-building exercise undertaken by the Canadian Collaborative Mental Health Initiative (CCMHI)—Seniors Working GroupFootnote 1 to identify key priority planning areas associated with the accessibility needs of older adults with complex health issues (Donnelly et al., Reference Donnelly, Le Clair, Hinton, Horgan, Kreiger-Frost and MacCourt2006). The resulting accessibility framework is intended to provide collaborative mental health planners, administrators, and providers with an understanding of the unique accessibility needs of older adults, and to enable them to embed strategies to address these issues within everyday practice.

Collaborative Mental Health Services for Older Adults

Studies have shown collaborative mental health care initiatives to be effective in the care of individuals with complex needs brought on by aging. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that specialized depression care managers (i.e., case managers specializing in mood disturbances), co-located with primary care services, can improve both depression and medical outcomes, and quality of life in older adults (Bruce, Ten Have, Reynolds, Katz, Schilberg, Mulsant et al., 2004; Callahan., 2001; Gallo, Zubritsky, Maxwell, Nazar, Bogner, Quijano et al., 2004; Unutzer, Katon, Callahan, Williams, Hunkeler, Harpole et al., 2002). Depression care managers have also been successfully used to increase depressed patients’ adherence to depression medication prescribed for diabetes or congestive heart failure (Donnie, Reference Donnie2004). Likewise, a number of recent reviews (Callahan, Reference Callahan2001; Klinkman & Okkes, Reference Klinkman and Okkes1998) have concluded that training of primary care providers, provision of informational support, and depression screening of older adults may improve recognition and initiation of depression-specific treatment in primary care. Further, Unutzer (Reference Unutzer2002) has suggested that collaboration between health care providers and community organizations (e.g., religious institutions, senior centres, public service agencies, senior housing facilities, and consumer organizations) may foster social opportunities for older adults at risk of, or experiencing, mental health issues, particularly those with dementia or a related illness.

Accessibility Issues Faced by Older Adults

Accessibility represents a fundamental issue affecting health care utilization by older adults (Bartels, Reference Bartels2004; Cradock-O’Leary, Young, Yano, Wong, & Lee, Reference Cradock-O’Leary, Young, Yano, Wong and Lee2002; Donnelly et al., Reference Donnelly, Le Clair, Hinton, Horgan, Kreiger-Frost and MacCourt2006). Individuals, as they age, are impeded by various factors, which determine the extent to which they use formal health care services. For instance, changes in social status arising from retirement, reduced income level, and bereavement can isolate individuals from everyday community life (Lepine & Bouchez, Reference Lepine and Bouchez1998). Consequently, they may not be aware of the full range of community services available to them. Likewise, older adults may experience decreased physical mobility, which can result in decreased attendance at health care appointments (Druss, Rosenheck, Desai, & Perlin, Reference Druss, Rosenheck, Desai and Perlin2002). Alternatively, elderly spouses caring for physically and mentally ill partners have an increased sense of burden and loneliness. In turn, these individuals may themselves acquire extended physical and mental health conditions (Clyburn, Stones, Hadjistavrapoulos, & Tuokko, Reference Clyburn, Stones, Hadjistavrapoulos and Tuokko2000) and experience greater difficulties in caring for their loved ones. Finally, shortages of family physicians, and specialized mental health services generally, can further exacerbate the difficulties faced by this group in accessing appropriate health care services (Dugue, Reference Dugue2003; Kaperski, Reference Kaperski2002; Kates, Reference Kates2002; Rockman et al., Reference Rockman, Salach, Gotlib, Cord and Turner2004). The challenge for health planners then is to ensure that collaborative mental health initiatives address not only the unique health needs of this population (through the integration of primary, mental health, and community supports) but also the degree to which these services are accessible to individuals who experience mobility, communication, and integration challenges.

Method

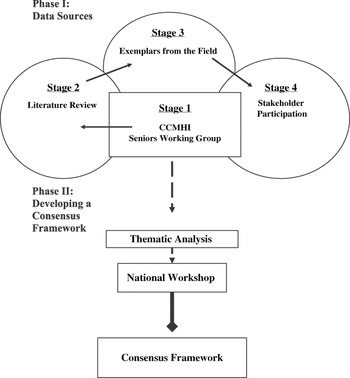

The CCMHI—Seniors Working Group (Donnelly et al., Reference Donnelly, Le Clair, Hinton, Horgan, Kreiger-Frost and MacCourt2006) initiated a national participatory consensus-building exercise to develop a preliminary framework on the accessibility needs of older adults. The purpose of the exercise was to draw out the collective wisdom of this diverse group to inform policy planning and implementation as it relates to collaborative mental health care services. The iterative methodological technique used to guide the consensus-building process (see Figure 1) employed a systematic process of converging evidence across a wide range of stakeholder positions (Barr & Dixon, 2000; Holmes & Scoones, Reference Holmes and Scoones2000).

Figure 1: Iterative stages involved in developing consensus framework

Phase I: Data Sources

Stage 1: Forming a National Interprofessional Steering Committee

The first stage in the consensus building process was to form a nationally representative interprofessional steering committee (referred to as the CCMHI—Seniors Working Group). The committee comprised a group of six opinion leaders from central, eastern, and western parts of Canada who had experience in family caregiving, social work, community nursing, geriatric psychiatry, family medicine, policy analysis, and program evaluation. The committee was responsible for overseeing the planning, implementation, and analysis of each phase of the exercise and the dissemination of findings.

Stage 2: The Literature

A review of the literature was conducted to examine the benefits and best practices of collaborative mental health care specific to older adults with complex health needs. An electronic literature search performed on Medline and PsychINFO included the key words “collaborative care,” “collaborative mental health care,” “geriatric mental health,” and “seniors’ health.” A total of 79 articles were selected for review.

Stage 3: Tacit Knowledge—Experiences from the Field

The working group appraised a total of 24 exemplars of collaborative services currently operating in the primary care and mental health fields that provide services to adults over age 65. Program descriptions comprised the following categories: (a) program rationale and description of activities, (b) program goals, (c) resources and technology, (d) funding, and (e) evaluation. These exemplars served as background for later stages of the consensus process including stakeholder selection and the identification of key practice strategies.

Stage 4: Stakeholder Participation

Members of the steering committee, in conjunction with other key informants from the field, identified five key stakeholder sectors. These sectors included the following: (a) multidisciplinary health professionals from mental health, primary care, and geriatric mental health; (b) non-government organizations, educators, and researchers; (c) policy planners; and (d) older adults with complex mental and physical health needs along with their family caregivers. A series of in-depth personal interviews were conducted with representatives from each group. A total of 26 interview participants were purposely selected across seven provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and P.E.I.). Two focus groups were also conducted, one with a seniors group and the other with a multidisciplinary group of service providers. Interviewees were asked to comment on the accessibility needs of older adults, particularly those with concurrent, chronic mental and physical health needs. Participants were also asked to comment on the organizational and system structures that may present barriers to adequately meet these needs.

Phase II: Developing a Consensus Framework

Thematic Analysis

An inductive thematic analysis was conducted on the information generated from the literature review, field descriptions, and stakeholder interviews. The aim of analysis was to identify resonant themes emerging from the data related to accessibility. The process involved multiple readings of the interview data, coding of textual data, and continuous sharing of findings with stakeholders (e.g., national consensus workshop and field consultants) (Denzin & Lincoln, Reference Denzin and Lincoln1998). The outcome of the analysis process was a preliminary framework of older adults’ accessibility needs. The analysis also highlighted effective practice strategies for increasing accessibility for this population. Two consultants with national and international experience in the field were asked to provide critical feedback on the initial findings.

National Workshop: Consolidation of the Field

The emerging themes derived from the consensus-building exercise were presented to an interprovincial and interprofessional audience at the National Best Practices Conference: Focus on Seniors Mental Health, co-sponsored by the Canadian Coalition for Seniors Mental Health (Le Clair, Donnelly, Kates, Horgan, MacCourt, Hinton et al., 2005). The workshop constituted the concluding stage in the development of the consensus framework and produced a final consolidation of needs, issues, and practice strategies to inform collaborative care planning and implementation. In total, 30 stakeholders including representatives from primary and mental health services, policy planning, research, education, and non-government organizations participated in the consensus workshop. Workshop participants explored the accessibility needs of older adults and attempted to incorporate new ideas and perspectives into the framework to reach saturation.

Limitations of the Consensus Process

The framework represents a preliminary foundation with which to begin to address the accessibility needs of older adults and thus begin to strengthen everyday collaborative practice. The framework, however, requires further refinement and broader representational input from the field. The diffuse nature of the geriatric field (e.g., geriatric mental health, long-term care, home care, and seniors associations), coupled with the need to develop the framework in a relatively short time frame,Footnote 2 limited the rigorousness we could apply to achieving a comprehensive representation. In the absence of a formal structure to identify potential stakeholders, the working group relied largely on word-of-mouth contact, personal connections, and existing provincial listings. The limitations in representation were further compounded by the fact that older adults with complex health issues and their caregivers face personal (e.g., difficulties with communication) and systemic obstacles (e.g., limited transportation and respite options), which limit their ability to participate in lengthy interviews. The framework would be strengthened and could only be considered complete once efforts had been made to create formal circles of representation across the full range of stakeholder groups that stand to inform collaborative health services for seniors.

Results

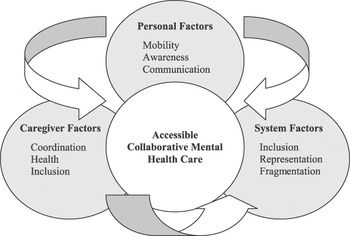

The thematic analysis conducted on the data revealed three theme areas—personal factors, caregiver factors, and systemic factors—that impact the degree to which older adults are able to access collaborative services (see Figure 2). Corresponding strategies for improving access to collaborative services were also revealed (see Tables 1 to 3).

Figure 2: Consensus framework on accessibility for older adults with concurrent and chronic health needs

Table 1: Strategies for addressing personal factors

Personal Factors

Mobility

Seniors (with complex mental and physical health needs) usually have multi-system problems, they usually have multiple medical problems, and their problems often include social and housing issues as well… and we need to offer services that make it easier for them to get these [various] needs met.

Mental Health AdministratorOlder adults experiencing concurrent, and chronic, mental and physical health issues are often limited by physical, intellectual, and functional challenges in their ability to physically access health care services. An inability to drive, for example, may impact the extent to which an older person seeks out the numerous services and supports required to address multiple interrelated health issues (e.g., optometrist, family physician, bereavement counselor, and mental health outreach services). Associated financial implications may also influence the extent to which older adults access health care services. An individual requiring the use of a wheelchair, for example, will incur additional costs for wheelchair transit. Notably, those individuals with dementia, who experience issues with memory loss and disorientation, may be unable to utilize any form of public transportation. Ultimately, the difficulty in physically accessing services can cause older adults to skip appointments or to limit the number of services from which they seek support. Re-conceptualizing the structure of collaborative care services (e.g., location, co-location, mobile) may enhance the degree to which older adults are able to access the multitude of services they require.

Resource Awareness

For instance, in my experience we have an elderly outreach team here that I have referred many people to, and everybody is totally surprised that it exists.

Mental Health AdvocateLifestyle changes after retirement can decrease the awareness that older adults possess related to available community resources. Therefore, older adults—particularly those with complex needs—may need help identifying available resources. Older adults may further require help in identifying key entry points into the health care system. In particular, mental health services tend to be very difficult to negotiate given a lack of any previous connection with the system. The stigma associated with mental health care can further discourage individuals from accessing this type of service. Given that primary care is likely to be the first place where most people, older adults included, initially seek help, embedding mental health services into primary care settings can help to maximize accessibility to these specialty services.

Communication

Actually, [length of appointments] has been a huge issue at this clinic, because we have such a huge seniors population in this area of the city that in fact our doctors aren’t seeing 22 clients a day. It is not possible with seniors.

Primary Care Service ProviderThe communication style of older adults is another variable that impacts accessibility. Older adults, for example, are less likely to discuss health matters in a rushed and busy environment. Older women in particular tend to have an indirect style of communication and may not feel comfortable asking to see a specialist. In fact, older adults in general may be less likely to seek second opinions. Specifically, older individuals with complex mental and physical health needs are often most comfortable in their own homes where they control the pace of life. This is particularly true of individuals who experience mental health symptoms such as dementia. Thus, slowing the pace of appointments and probing for additional information can be useful in creating an environment where older adults actively participate in their own health care. (Table 1 lists strategies for addressing personal factors.)

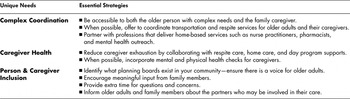

Caregiver Factors

Complex Coordination

I suppose I could call [the family doctor] and he’d probably see [my husband]. It’s the energy, the thought of okay, I have to [dress him]—you know if I don’t have a caregiver there I have to get him ready. We have to be there at a certain time, which is hard. I have to get him into the car. Take him out of the car when we get there, into a wheelchair, back again, and up to where this doctor’s office is. It is huge energy. It’s why I don’t do it except if I have the [attendant] with me.

Family CaregiverWhen older adults experience complex health issues (e.g., dementia coupled with health disease), family members often assume responsibility for coordinating health care appointments. Arrangements around multiple health conditions and associated services can be a burden for caregivers. For example, an older adult who requires the use of a wheelchair will need the services of an attendant (to physically dress her/himself) and para-transit (for transportation) in order to visit a single service provider (such as the family physician). These arrangements may need to be made several times to accommodate multiple health care appointments. The difficulty in coordinating multiple services (e.g., home care, respite care, transportation, and multiple providers) is compounded when individuals and their caregivers are exhausted and overwhelmed from the day-to-day realities of living with complex health conditions. Increasing the option of receiving collaborative services in the home as well as the availability of multiple and diverse supports under one roof may address many of these coordination difficulties.

Caregiver Health

Ya, [the family physician] sets aside a certain part [of time for me], if I need him. But he’s mainly concerned with [my husband’s physical needs]….

What really helps me, … is kind of knowing what will happen. What to expect, so that I can kind of plan for this, or be aware of [certain] signs ….

Family CaregiverThe extent of care provided by informal caregivers is integral to meeting the needs of older adults with complex health needs. To maximize the ability of caregivers to attend to the health of their loved ones, it is important that added time and attention be reserved to address their questions and to ensure they are informed about their loved one’s health issues. Likewise, the difficulties inherent in coordinating the health of their family member may mean that caregivers do not regularly attend their own health appointments. This decrease in attending appointments can diminish the health of the caregiver, particularly considering the strain of the caregiver role (e.g., back strain from lifting, or depression due to isolation). Combining the health care appointments of older adults and family caregivers can be a useful strategy both in addressing caregiver concerns and in preserving their health.

Person and Caregiver Inclusion

Well, I don’t know if they talked to each other but reports went back around … ya,

I think that’s mainly what happened. More or less reports went to the family

physician and [the geriatrician] and so forth.

Family CaregiverCaregivers can feel left out of the decision-making process concerning their loved ones. At times, it may feel as though collaboration is going on around them (from service provider to service provider) but does not involve them directly. Often, caregivers wish that they and their family member were more involved in the formal collaboration process. Involving older adults with complex needs in health care decision making can be a challenge, particularly in instances when the person’s ability to communicate is affected. In such cases, health care providers may need to be innovative in creating ways to enable decision making on the part of older adults. One way to address this is by actively involving family members and key community partners (e.g., Alzheimer’s Society) in the collaborative process. (Table 2 lists strategies for addressing caregiver factors.)

Table 2: Strategies for addressing caregiver factors

Systemic Factors

Senior Inclusion

In a publicly funded world, we are at the mercy of what the electorate places a priority on—seniors with mental health needs are never the priority.

Mental Health AdministratorSeniors, families, and seniors’ organizations are often excluded from planning initiatives because it is assumed that general mental health services adequately represent their needs. Hence, the unique and diverse needs of seniors experiencing complex health issues are often not adequately represented in these fora. Although seniors experiencing significant mental and physical health issues and their family members can be overwhelmed by the impact these issues have on their lives, many are interested in having input at program, organizational, and systems levels. Collaborative care initiatives should offer seniors, including those with complex health issues, the opportunity for participation as consumer representatives. Additionally, seniors without serious health issues are well equipped to serve as advocates to give voice to seniors’ needs on advisory boards and committees.

Broad Stakeholder Representation

[The pharmacists] are so willing to help you all the time, and the doctor will give you a prescription but he won’t go into any of the details about it, he just says take this to the pharmacist. I’m a perfect nuisance to pharmacists and they are so helpful.

Older Adult Service UserThe complex health needs of older adults necessitate a broad spectrum of health and community partners. For example, older adults who experience concurrent and chronic mental and physical health issues must collaborate with multiple health care providers (family physicians, mental health practitioners, specialists), community providers (pharmacists, banks, lawyers), and family members (spouses, children) to address various health and related social issues. Similarly, the mobility and cultural issues faced by older adults force them to rely on community supports to a larger extent than other societal groups. Hence, the people—such as family members, local librarians, taxi drivers, neighbours, and landlords—who first come into contact with older adults are just as integral to the collaborative process as are traditional health care providers. Promoting collaboration among a broad base of stakeholders (in particular, relevant community partners) may increase the extent to which older adults access and benefit from collaborative mental health services.

Service Fragmentation

There is no organized kind of unit around ensuring that seniors get the resources they need, when they need it, and so on… [systemically] it’s very fragmented.

Policy AnalystCurrent health care policy is not responsive to the developmental changes associated with aging. As older adults continue to age, they become increasingly susceptible to acquiring additional and chronic health conditions. Typically, each developmental change in need brings with it a new set of services, service providers, and service locations. For example, individuals may find themselves in a position where they no longer meet the age, mobility, or cognitive criteria to receive a particular service. A person who was once receiving physiotherapy services in a day program but who has now reached the age limit for that program may be unable to receive physiotherapy at the long-term care home to which she or he has been transferred. This can be disorienting for older adults who have become accustomed to a particular set of services and practitioners. Collaborative policies between service organizations and service sectors are required to minimize the fragmented care experiences of older adults. (Table 3 lists strategies for addressing systemic factors.)

Table 3: Strategies for addressing systemic factors

Discussion

The growing number of seniors within our society and the complexity of their health issues compel us to devise better health care policies and practices to meet their needs. The values that form the basis of both mental health and primary care reform stand to inform changes which will benefit the health of our senior population. In particular, collaborative services that address an array of concurrent and interrelated health issues are coming to the forefront of Canada’s health agenda. Older adults, however, will only benefit from the transformation if their unique accessibility needs are considered in policy and planning activities.

Ultimately, the potential that collaborative services hold for identifying health issues sooner may lessen the number of chronic illnesses experienced by older adults generally. Collaborative mental health care initiatives employ structures that better enable older adults to access a broad range of health care and community-based supports (e.g., seniors associations, bereavement counselors, cultural interpreters, home care, pharmacists, legal councilors, and family members). The ease with which multiple providers are accessed also promotes regular attendance at health care appointments. Likewise, collaborative care initiatives promote self-management strategies to involve service users in personal goal-setting, action-planning, and problem-solving activities. In being provided with roles and responsibilities around their health care (and in being supported to carry them out), older adults are encouraged to become knowledgeable about their health care needs. Subsequently, they are also more likely to maintain proper health care routines.

Currently, the issues of seniors often become subsumed within large policy and planning sectors (e.g., mental health, acute care, or housing and social welfare). Yet the information we garnered from the consensus-building exercise demonstrates that the needs and issues faced by older adults differ significantly from those of their younger counterparts. Embedding strategies for accessibility into organizational and systems planning initiatives will considerably strengthen the degree to which this critical health care user group of older adults can benefit from collaborative care initiatives. The impact of the collaborative mental health care model on the overall health care system will likewise be strengthened through systematic efforts to ensure accessibility for this growing group of intensive-health-service users, and thereby easing the strain on health care dollars and system overload.