On September 10, 2012, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, Jason Kenney, announced that the federal government would revoke the citizenship of 3100 Canadians accused of fraudulently obtaining citizenship. In this brief, but vigilant demonstration of policy authority at Ottawa's National Press Theatre, Kenney asserted that his department was in the process of investigating nearly 11,000 individuals from more than 100 countries for “attempting to cheat Canada and Canadians” by lying on their citizenship application or by committing residence fraud, the practice of paying for accommodation in Canada, but living elsewhere. “Canadian citizenship,” he declared, “is not for sale” (Kenney, Reference Kenney2012).

Media reaction to Kenney's controversial proclamation was swift. While some outlets pointed fingers at unscrupulous immigration consultants, others levied accusations at immigrants themselves, noting that Canada's generous social assistance programs and government-facilitated health care program attract some to obtain citizenship for its many benefits but then to reside outside the country. Soon after, the legal and journalistic communities reflected on the implications of Kenney's statements through the lens of the rights and responsibilities of immigrants and the legal feasibility of leaving an individual stateless. By the end of the media blitz, the average Canadian reader had been exposed to numerous frames, or lenses of understanding, through which they could perceive immigration.

This episode is only one example of media framing of immigration. Framing, the act of communicating information in a way that promotes a particular understanding, is a mainstay of the political communication literature but one with very real world impact on the way the public understands policy issues (Chong and Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007b; Entman, Reference Entman2004; Price and Tewksbury, Reference Price, Tewksbury, Barnett and Boster1997). Frames are more than the positive or negative lenses through which we view an issue; they are the heuristics and thematic cues obtained (largely) through news media that help the public synthesize and integrate new information. Immigration, for example, can be framed as a threat to security or a mechanism for labour force growth. Extending citizenship to newcomers can equally be perceived as an economic necessity or a humanitarian act. Much of the perspective taken depends on the framing, the effects of which almost always galvanize public opinion (Benson, Reference Benson2010, Reference Benson2013; Boswell et al., Reference Boswell, Geddes and Scholten2011; Fleras, Reference Fleras2011; Fleras and Kunz, Reference Fleras and Kunz2001; Grimm and Andsager, Reference Grimm and Andsager2011; Mahtani, Reference Mahtani2001).

Media framing matters to public perceptions of policy, particularly in an area like immigration where people often lack personal experience. Understanding the evolution of frames is, therefore, an important piece of how we conceive of the link between the public's political priorities and policy makers’ responses (Baumgartner and Jones, Reference Baumgartner, Jones, Rochefort and Cobb1994; Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Jones, Leech, Iyengar and Reeves1997; Shanahan et al., Reference Shanahan, McBeth, Hathaway and Arnell2008; Soroka and Lim, Reference Soroka and Lim2003). While the multi-directional relationships that exist between media, public policy and public opinion often pose challenges to precisely extracting media effects (Soroka, Reference Soroka2002), there is still much that can be said about how the content and tone of immigration frames change over time in response to major policy changes or focusing events. In other words, there is still an interesting causal story that can be told from the side of media responses to external changes, even when causal claims in the other direction are limited.

This article examines the content of media framing across two immigrant-receiving countries, Canada and Britain, that have similar policy frameworks but receive substantively different levels of immigration. The hypothesis presented here is that media framing is not static over time; rather, it is highly dynamic and subject to punctuations based on policy changes and focusing events. This assumption is a routine one, but it is important to confirm if the academy wishes to have a clear understanding of how framing changes over time and space. I test this assumption using automated content analysis (ACA) of media's framing of immigration in CanadianFootnote 1 and British print news sources from 1999 to 2013. This period contains two large-scale focusing events with national and international implications (9/11 and the 2005 London bombings), the effects of which have been reported to change the way media and the public characterize newcomers (Boswell et al., Reference Boswell, Geddes and Scholten2011; Charteris-Black, Reference Charteris-Black2006; Huysmans and Buonfino, Reference Huysmans and Buonfino2008). In other words, if we expect event- or policy-driven change in framing, it would likely be manifested in this period. This article also promotes an inductive technique to extract frames from media content (see Mahon et al., Reference Mahon, Lawlor, Soroka, Marland, Giasson and Small2014), a departure from framing analyses that are heavily dependent on a researcher's pre-existing assumptions about policy narratives.

Immigration Policy and National Context: Comparing Canada and Britain

Comparing immigration framing in Canada and Britain is an acknowledgement of the commonalities in both countries’ immigration policies and their media systems. In the postwar era, Canada and Britain stand among the top ten Western immigration-receiving countries (Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2013). They have cultivated similar frameworks for immigration policy that encompass varied economic, human rights and security-oriented legislation. Similarities carry into their respective media environments. Both countries are classified as liberal market media systems, combining public service broadcasting (the BBC and CBC) with strong private commercial news interests (Hallin and Mancini, Reference Hallin and Mancini2004).

A critic might suggest that Britain and Canada are too divergent to compare. Canada, a country that has embraced and still retains widespread support for immigration, as well as an official policy of multiculturalism would appear on the surface a world apart from Britain, with its policy of “managed migration” and public support for a recently proposed cap on the number of immigrants admitted yearly. However, the immigration policy trajectories and outcomes of these two countries share some remarkable similarities motivated by their shared need to address rapidly changing demographics while maintaining the integrity of national borders in an increasingly security-oriented environment.

A short history of the principal moments in policy development illustrates the striking similarities and, at times, interdependence of these two immigration and refugee policy regimes (see Table 1). Driven by the increase in postwar era migration, it was the Canadian government that made the first substantive move toward defining citizenship and immigration policy. In response to the increased supply of immigrants from the British Isles as well as many other post-conflict areas of Europe, the Mackenzie King Liberal government instituted the Citizenship Act of 1946, creating a distinct Canadian citizenship, separate from that of Britain. Britain responded to the Canadian initiative and similar policies from the Commonwealth by instituting the British Nationality Act (1948), viewed as an attempt to alleviate the economic pressures of a rapidly fragmenting Commonwealth (Hansen, Reference Hansen2000).

Table 1 Principal Policy Moments: Canada and Britain (1945-Present day)

*Note: Many policies listed above have implications for more than one policy domain.

In the decades that followed, both countries introduced laws that expanded criteria for migration; the principal difference was in the motivation. While Canada's previous legislative efforts included controversial restrictions around race and ethnicity, by 1967, it had moved away from racially exclusionary selection mechanisms, toward skills-based criteria. Contemporaneously, Britain's Conservative government refined the rules on inclusivity in citizenship, introducing the Commonwealth Immigrants Act (1962). The act limited migration of Commonwealth citizens to Britain and was roundly criticized by the Labour opposition for its discriminatory effects on immigrants from Africa and South Asia.

Under pressure to address increasing racial discord, Britain adopted the Race Relations Act (1965) and the Commonwealth Immigrants Act (1968), prohibiting all institutionalised racial discrimination, while implementing jus sanguinus sanctions that allowed only those individuals with at least one parent or grandparent born in Britain to immigrate. This principle was strengthened further in the British Immigration Act (1971), which introduced the concepts of partiality and right of abode to the citizenship framework, as well as the British Nationality Act (1981), which introduced a tiered citizenship regime for Commonwealth citizens. The adoption of the British Immigration Act in 1988 further entrenched both residence and employments restrictions.

By comparison, Canada's entrenchment of economic and demographic criteria for migration in the 1976 Immigration Act might suggest an earlier movement toward inclusivity in immigration. The outward focus of the policy was to more clearly define the family, independent and refugee immigrant classes, and to place limits on the discretionary powers of the minister to personally influence immigration by requiring the number of special permits issued every year to be made public. A by-product of this policy was to entrench more stable levels of immigration to Canada (ranging from 100,000 to 250,000 per year), a trend that continuous to this day.

Further similarities between the two countries’ regimes can be found in recent overtures made by sub-state governments to influence immigration outcomes. Both countries have legislated some (albeit limited in the case of Britain) devolution of immigration policy authority to sub-state governments whose political autonomy and divergent policy preferences allowed them to create smaller immigration regimes within the framework of national law. In 1991, the Canadian federal government expanded the province of Quebec's ability to select and receive immigrants deemed “best suited” to live in Quebec through the Canada-Quebec Accord (similar agreements were later extended to other provinces). The British government did comparatively less by way of devolution, reserving power over immigration during the devolution agreement that created the Scottish parliament in 1998. The Scottish parliament did, however, offer the Fresh Talent Initiative in 2004, designed to encourage foreign graduates of Scottish universities to remain in Scotland to pursue employment.

Enthusiasm for the economic benefits of migration was moderated in some quarters in the wake of the terrorist acts of September 2001. By this point, the structural patterns of immigration to each country had changed substantially. While Canada had kept levels of migration reasonably stable from the end of the twentieth century into the twenty-first, Britain, saw remarkable increases in immigration from nearly 300,000 in 1990 to almost 500,000 by 2001 (see Figure 1). The ethno-racial composition of immigration had also drastically changed, with increasing numbers of non-white immigrants from Southeast Asia to Canada, and Central Asia and North Africa to Britain. Both countries responded to the threat of terror attacks (and actual attacks in the form of the London underground bombings of July 2005) by adopting restrictionist policies such as the Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act (2009) in Britain, and the Protecting Canada's Immigration System Act, adopted in 2012 in Canada. Both countries broadened powers to arrest and detain suspected security threats, expanded immigration officers’ powers to collect biometric information from incoming migrants and refugees, as well as restricted the flow of migrants by adopting “safe third country” agreements in tandem with neighbouring countries. These acts, though contested by advocacy groups and some on the political left, appeared to create an unofficial set of tiered preferences by government for particular migrant groups (Buonfino, Reference Buonfino2004; Roach, Reference Roach2005).

Figure 1 Immigration Levels by Country (Canada and Britain)

Policy motivations, such as economic need, security, and human rights (via refugee status), are not Canada and Britain's only link. Increasing diversity is a socio-political reality in both countries. Foreign-born individuals make up just over one-tenth of the British population in the aggregate, though the percentages of non-British born in urban centres such as London, Manchester and Birmingham are much larger (Lawlor, Reference Lawlor2015; Rienzo and Vargas-Silva, Reference Rienzo and Vargas-Silva2012). Canada's urban centres are also increasingly diverse; over 40 per cent of Toronto and Vancouver residents identify as non-white, and recent estimates place the number of foreign-born in Canada at over 22 per cent of the total population (National Household Survey, 2011). Where these societies do not align, however, is in their respective public opinion toward immigration levels (see Figure 2). Whereas Canadians remain largely open to immigration, a majority of British respondents have responded negatively to the number of immigrants admitted, many supporting Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron's initiative to restrict the admission of immigrants.

Figure 2 Public opinion in agreement that “There is too much immigration to Canada and Britain”

Framing Immigration in the Media

Given the complexity of public policy and the numerous, simultaneous policy considerations that a citizen encounters on a daily basis, media framing plays a central role in cultivating a shared understanding of political issues such as immigration. Media framing, as it was initially conceptualised by Gamson and Modigliani, functions as the “central organizing idea or storyline” (Reference Gamson, Modigliani, Baungart and Braungart1987: 143) that guides audiences to a particular understanding of an issue. While the widely expanding interest in media framing is challenged by the lack of consensus around definitions (De Vreese, Reference De Vreese2005), the study of framing has vastly expanded over the past two decades and has grown to incorporate subject-oriented studies on immigration, among other policy issues (Brabeck et al., Reference Brabeck, Lykes and Hershberg2011; Grimm and Andsager, Reference Grimm and Andsager2011; Mahtani, Reference Mahtani2001; Vliegenthart and Roggeband, Reference Vliegenthart and Roggeband2007).

Despite an expansion in the framing literature over the past two decades, the academic community still has a piecemeal understanding of how the media frame immigration. Much of the work on this subject has been country specific and focused on a narrow time frame. Most studies of American immigration news coverage found the issue disproportionately framed in terms of the perceived “threat aspects” of immigration, such as economic threat (projecting jobs), threats to social programs (fraud) and threats to security (terrorism or crime) (Fryberg et al., Reference Fryberg, Stephens, Covarrubias, Markus, Carter, Laiduc and Salido2012; Merolla et al., Reference Merolla, Ramakrishnan and Haynes2013; Pérez Huber, Reference Pérez Huber2009). The effects of these frames, as noted by Benson (Reference Benson2010: 16), is to create a series of dramatic narratives that emphasize episodic events, such as an attempt at fraud or an illegal border crossing, and de-emphasizing a constructive debate that would necessitate a more complete understanding of the policy context around immigration.

Cross-national studies on immigration and media point to a number of frames found in news content, including security, economy, employment, gender equality, multiculturalism or diversity (Benson, Reference Benson2010, Reference Benson2013; Vliegenthart and Roggeband, Reference Vliegenthart and Roggeband2007). Canadian research has yielded several studies that highlight the diversity of immigration frames used in the press. Despite a history of state-sponsored multiculturalism and depictions of the Canadian immigration system as culturally distinct (Reitz and Breton, Reference Reitz and Breton1994), scholars point out that, in the aggregate, framing of immigration varies from non-existent (for example, the exclusion of immigrants in the media) to negative—even, at its worst, racist framing that emphasizes particular considerations dependent on the ethno-racial group being discussed (Abu-Laban and Garber, Reference Abu-Laban and Garber2005; Fleras, Reference Fleras and Singer1995, Reference Fleras2011; Henry and Tator, Reference Henry and Tator2002; Mahtani, Reference Mahtani2001).

The Canadian research on framing also highlights the media's focus on framing immigration in terms of threat factors (Fleras, Reference Fleras2011). These are often viewed as localized or regional considerations that have worked their way upwards into the national dialogue by finding voice in federal representation. Common frames include scarcity in resources and employment, with an emphasis on job qualifications, competition for social services, the threat of fraud or illegality and threats to nation building (Bradimore and Bauder, Reference Bradimore and Bauder2012; Fleras and Kunz, Reference Fleras and Kunz2001). Even in a context where immigration and acceptance of refugees is largely viewed as positive, media use a variety of problematized narratives to describe immigration and integration into society.

In Britain, a similar negative discourse has emerged in the political space and has been reproduced by the media in its coverage of immigration. Analyses that comment on the broader political discourse around immigration point to a securitization of immigration, particularly as it relates to refugee and asylum cases (Huysmans and Buonfino, Reference Huysmans and Buonfino2008; Kaye, Reference Kaye, King and Wood2013). Other studies describe the elite discourse as focused on event-driven threats (Shehata, Reference Shehata2007), disaster-based narratives (Charteris-Black, Reference Charteris-Black2006), and security threat rhetoric (Huysmans, Reference Huysmans, Miles and Thränhardt1995). While some (for example, Boswell et al., Reference Boswell, Geddes and Scholten2011) disagree that the framing of immigration has been exclusively security driven, there is reasonably clear consensus that British news media rely heavily on the rhetoric of illegality and security in discussions of immigration.

While there appears to be broad thematic consistency across countries, cross-national media analysis will help draw out whether these similarities extend beyond broad themes, and whether there is any variation in the timing and presentation of frames. Comparative analysis has the potential to highlight the subtle variations that exist due to factors such as journalist style, political permissiveness and media type (see Benson, Reference Benson2010; Benson et al., Reference Benson, Blach-Ørsten, Powers, Willig and Zambrano2012). To do so, I borrow from Iyengar's conception of thematic and episodic frames. Thematic frames place issues in a general or abstract context, whereas episodic frames often take the form of personalized stories or event-specific news (Reference Iyengar1991: 22). Because the ACA technique reviews thousands of stories, looking for personalized stories or event-specific details becomes nearly impossible. This is less concerning from a scholarly perspective since episodic coverage has been criticized for promoting anecdotal or shallow coverage (Boykoff, Reference Boykoff2006). Thus, I use a broad lens on the issue, considering a frame to be a particular thematic emphasis on the primary subject: immigration. Given the dynamic nature of media, I expect that frames may be variable or resilient across time and space, and they may equally be event driven or context specific. Exploring the range, prominence and tone of frames, how they have changed or remained stable over a fifteen year period is the task of the next section.

Data

Recent advances in digital media indexing now allow the academic community to use a wider lens on the study of news media, providing useful macro analyses of the breadth of frames that the public has been exposed to over time. The following analysis uses print news coverage from the top three circulating broadsheet newspapers in Canada and Britain, respectively (Canada: The Globe and Mail, The National Post and The Toronto Star; UK: The London Times, The Daily Telegraph and The Guardian). All are nationally distributed with audiences from all over Canada and Britain. While The Star's coverage is far more locally focused than the other five papers, it remains the largest circulating newspaper in Canada, also representing the country's largest immigrant-receiving city. In this context, newspapers are more useful than television broadcast transcripts because they articulate a wider number of issues on a daily basis and are not reliant on addressing accompanying images, which contribute to framing effects in a way that is extremely difficult to control for in an ACA study.

While the British and Canadian news media markets are similar enough to be grouped together under Hallin and Mancini's “liberal market systems” classification, they stem from two different journalistic traditions. The Canadian and British print markets are both stratified by left-right ideology (Britain's arguably more so); however, the British print news market is also stratified by social class with broadsheets and tabloids catering to two different populations.Footnote 2 By contrast, the Canadian market is much more homogenous, with major cleavages (namely language) embedded in different newspapers, but not necessarily reproducing different types of content. In this article, I exclude the mass-market national tabloid market (or “red-tops”), popular in Britain, though far less common in Canada, as comparability across cases would be at risk. Broadsheet newspapers, of course, do not perfectly encapsulate the national mood, nor are they perfectly representatively of a country's media landscape, but they are “likely to embody a system's dominant professional ideals; because of their agenda-setting role, they are important to study in their own right” (Benson et al., Reference Bleich2012: 26).

Querying the Factiva database for “immigration,” “immigrant(s),” “immigrate(s/d/ing)” or “refugee(s)” in the headline from 1999 to 2013 yields a total of 10,542 stories, 5274 from Canadian news sources and 5268 stories from British print news sources. As previously mentioned, the time period under investigation here is meant to capture not only immigration coverage in the recent past, but also to serve as a pre/post analysis for two major global focusing events, 9/11 and the 2005 London bombings, both of which had implications for immigration and border security.

There are three facets to the following analysis: identifying and extracting frames from the news coverage, assessing the frequency of frame coverage (and its change over time), and assessing the tone of coverage (and its change over time).Footnote 3 Scholars who study framing recognize the challenges in determining what constitutes a frame, so much so that there is variability in the procedures suggested for identifying them in content. That said, Chong and Druckman (Reference Chong and Druckman2007a: 106–07) argue that there are a few shared standards, at minimum, that must be met to identify framing in written communication. According to the authors, there must be (a) an issue or event, (b) attitude(s) toward that issue or event, (c) an inductively created coding scheme usually guided by academic and/or popular literature, (d) sources for content analysis. Similarly, Cappella and Jamieson's (Reference Cappella and Jamieson1997) criteria for a frame consists of: (a) identifiable conceptual and linguistic characteristics; (b) common observation in the news media; (c) distinguishable elements from other frames, and; (d) some measure of intersubjectivity. The approach used here adheres to these requirements and expands on a new method (see Mahon et al., Reference Mahon, Lawlor, Soroka, Marland, Giasson and Small2014) to inductively identify frames.

Discovering frames in content is, according to Gamson (Reference Gamson1992), an inherently inductive approach. I use a three-stage process to inductively extract frames from text using unsupervised computer-assisted clustering, beginning by inductively extracting the most commonly used substantive words and phrases from the text itself.Footnote 4 I select frequently occurring words and phrases (such as “temporary foreign worker” or “asylum claimant”), excluding those that lack substantive meaning in the context (such as “month,” “nickel” and “people”), also excluding proper nouns. Entries are clustered according to how they relate to one another based on an underlying co-occurrence (Jaccard) coefficient. The result is a hierarchical cluster analysis or dendrogram.

Hierarchical clusters or dendrograms (available in the online appendix) are tree-like structures with clusters of words and phrases forming branches. In this case, clusters are formed based on the correlations between words and phrases in the same paragraph. Where there is internal consistency in the types of words and phrases used together each branch will correspond to a potential frame, the topic of which can be identified through the applicability of the words and phrases (for example, “joblessness,” “employment,” “experienced labourer,” would correspond to an economic frame). The structure of frames does not have to correspond on a one-to-one level to known arguments or categories of discussion in the popular or academic literature.Footnote 5 It is possible that more than one cluster could validate a frame if there were strong sub-frames at play (security could be reasonably broken up into human security and border security). As Grimmer and Stewart point out, however, human intervention is needed to validate that the clusters pointing to each of these branches identify a frame and are “theoretically interesting” (Reference Grimmer and Stewart2013: 3).

Below, I summarize each country's immigration frames derived from the dendrograms grouped by thematic area. Similar to the policy contexts in Britain and Canada, some shared characteristics come to light. There are nine clusters in total in the Canadian dendrogram pointing to five thematic issues:

-

- Refugee and asylum: Including discussion of human smuggling, refugee claims/status, deportation and human rights

-

- Illegality and security: Including discussion of law enforcement, terrorism, organized crime and illegal migration

-

- Economic and labour considerations: Including discussion of employment, foreign credentials, demographic changes and the labour force more broadly

-

- Social services: Including discussion of health care, social assistance, language training and settlement services

-

- Diversity: Including discussion of visible minority status and ethnicity

The British dendrogram points to a very similar dialogue with clusters highlighting to the same five thematic areas with subtle but relevant distinctions from the Canadian case.

-

- Refugee and asylum: Including discussion of asylum seekers, determination centres, deportation, as well as some discussion of rights and citizenship

-

- Illegality and security: Including discussion of fraud, terrorism, and organized crime

-

- Economic and labour considerations: Including discussion of employment, demographic changes, migrant labour and the labour force more broadly

-

- Social services: Including discussion of health services, social housing, social security and claiming benefits

-

- Diversity: Including discussion of ethnic minorities and race relations

With few a priori assumptions, the hierarchical clustering of media data is observed to be similar across cases, yet there are some notable differences. For example, in the Canadian case, the use of the phrases such as “illegal immigrant” and “illegal migrant” are associated with the illegality frame, whereas in Britain, they are associated both with the refugee and asylum frame and the illegality frames. In the Canadian case terms such as “visible minority(ies)” comprise a good number of references associated with diversity, whereas in Britain, references are largely to “race” and “race relations.” Finally, evidence of broad population trends such as “birth rate” and “population growth” turn up directly in the British economic frame, whereas they are distinct from the Canadian economic frame.

Having identified a series of frames from the texts, I create a classification dictionary for each of the five frames (social services, economic or labour considerations, illegality, refugee and asylum, and diversity), coding each mention of a framing term contained in the dictionary. Owing to the potential overlap in frame subject matter, articles could be coded under multiple frame categories (the inclusion of a news story in the social services frame did not preclude it from being coded in the refugee frame if both were mentioned).

Frame Coverage over Time

Recall the initial research questions set out in the paper: how does news media frame immigration in Canada and Britain? How have the volume and tone of these frames changed over time? From the results below, we can contrast the two countries’ main print media outlets as pursuing two different strategies to framing immigration. While the Canadian print media frame immigration in an event-driven manner, British print media show more durable framing effects applied over extended periods of time, possibly creating a more lasting impact on public perceptions of immigration (though this hypothesis is not tested here).

Table 2 presents the proportion of articles in each paper that reference a frame cue (that is, a framing word or phrase in the abovementioned dictionary). While we might anticipate left-right ideology or national considerations to dictate the type and frequency of frames, Table 2 shows little indication of such a trend. Rather, any differences, few though they may be, are cross-national. Canadian papers reference social services frames in the context of immigration coverage more frequently than British papers, with the Toronto Star dedicating the highest proportion of coverage (31.9% of all articles used a social services frame) in their immigration reporting, but The Telegraph, a right-of-centre paper and The Guardian using social services frames in roughly equal amounts. Economic frames were mentioned with nearly the same frequency in both countries with no indication of ideological differences in the volume of economic framing. Illegality frames were mentioned in Canadian papers more frequently than British papers (61% of all National Post articles on immigration, and 57% of The Star's immigration coverage), though with few differences between papers that feature more liberal or conservative views. Both Canadian and British papers rely extensively on refugee and asylum frames; numbers are roughly similar across national papers. Finally, Canadian papers out-report British papers on the subject of diversity, perhaps not a surprising finding given Canada's longstanding rhetoric of multiculturalism and Britain's relatively recent dialogue on the merits and limits of multiculturalism in British society.

Table 2 Frame Frequency (Canada and Britain)

*Percentages reported in table represent % of articles in newspaper that use the framing cue at least once. Kruskal-Wallis tests significant at the .001 level.

Disaggregating framing data by quarter in Figures 3 and 4 illustrates comparatively how frequently each frame was used and how those rates change over time (papers are aggregated by country). Whereas the Canadian case shows only slight variation in the volume of social services, economic/labour and diversity frames over time, the British case shows a stark increase in both types of framing in the period from early 2004 to 2007, in 2010, and again in 2013. Increases in Canadian coverage are temporary, lasting only a single quarter. By comparison, increases in the use of frames in British coverage appear to be much more resilient; spikes are more durable, lasting between two quarters to multiple years.

Figure 3 Immigration Frame Coverage by Quarter (Canada)

Figure 4 Immigration Frame Coverage by Quarter (Britain)

The illegality frame panels in Figures 3 and 4 highlight that the rate of Canadian and British framing are almost the inverse of one another. The frequency of the illegality frame in Canadian coverage of immigration is highest in 1999q3, 2000q2, 2001q4 and 2010q3. Each of these represents a focusing event: the increase in framing in 1999 was driven by coverage of the offshore arrival of four boats containing 599 refugees fleeing the Fujian province of China. The 2001 increase was a response to the increased rhetoric around potential security threats brought by new Canadians in the post-9/11 context. The 2002 coverage focused on Mohamed Harkat, an Algerian-born terror suspect whose residency in Canada was denied by the Federal Court. The 2010 increase in coverage was, similar to 1999, driven by coverage of MV Sun Sea incident, the arrival of 492 Tamil refugees off the coast of Vancouver in August of that year. By extension, coverage of the refugee frame is most prominent in 1999q3 and 2010q2, corresponding to these two high profile refugee cases. In sum, immigration framing in Canadian papers appears to be largely event driven; peaks of interest are reasonably short-lived, with framing dropping off considerably shortly after.

By contrast, British news media's tendency to use illegality and refugee frames appears less episodic than Canada's. Whereas Canadian illegality framing peaked in the late 1990s and early 2000s, British framing increases in early 2004 and remains robust until 2007. While this period includes the London underground bombings, there is no noticeable spike in coverage for that time point (2005q2). Additionally, there is no dramatic increase in the use of illegality framing post-9/11, suggesting that the attack on the World Trade Centre did not resonate as deeply with British news framing of immigration as it did in Canada. The use of refugee framing shows a dramatic rise in Britain between 2004 and 2006, with another peak in 2013q4. The earlier period follows the adoption of the 2003 and 2005 treaties of accession that opened up migration opportunities for residents of the A8 countries (those countries that joined the EU during the 2004 enlargement), whereas the 2013q4 peak in coverage was driven by external considerations, namely the increase in Syrian refugee applications following mass exodus from the Assad regime. Consequently, the majority of framing shifts were just that, shifts rather than spikes, in response to the changing immigration framework and socio-political realities.

As previously mentioned, frames do not operate in isolation from one another; rather some frames appear to be regularly used in tandem (see Pearson's R correlations in Tables 3 and 4). In Canadian immigration coverage, there is a strong correlation between social services and economic frames (r = .74, p < 0.001). However, this is overshadowed by the strength in correlation of illegality and refugee frames (r = .89, p < 0.001). Diversity notably positively correlates with all frames, with the exception of refugee frames, with which it correlates negatively (r = −.46, p < 0.001), suggesting that Canadian print media may associate coverage of multiculturalism or ethno-racial harmony or discord with immigration, but not migration through refugee and asylum channels. Comparatively, the British print news appears to draw upon multiple considerations when framing immigration. The high correlation between social service and economy/labour frames suggests that British media (like Canadian media) associate topics such as the use of training services or access to social welfare services with access to the labour market and economic need for migration. Additionally, social services and economic frames are individually strongly correlated with illegality frames (r = .81 and .88 respectively, p < 0.001), highlighting a discourse related to fraud or abuse of social services and illegal access to the labour market. Finally, diversity is highly correlated with all other frames, suggesting that ethno-racial diversity or “race relations” is salient to all discussions of immigration in the media.

Table 3 Frame Correlations (Canada) using quarterly data

*Pearson's R p. < 0.001.

Table 4 Frame Correlations (Britain) using quarterly data

*Pearson's R p. < 0.001.

Tone of Coverage over Time

Looking at the volume of coverage can shed some insight into the frequency with which the public may be exposed to specific frames; however, assessing the tone of that coverage yields valuable insights about how the valence qualities of news coverage can impact perspectives toward immigration. As scholars of political communication often note, text conveys information beyond what is printed, therefore acknowledging the capacity of tone to impact framing outcomes is essential (Pennebaker et al., Reference Pennebaker, Mehl and Niederhoffer2003: 550; Young and Soroka, Reference Young and Soroka2012). To uncover the tone of immigration-related frames, I use the Lexicoder Sentiment Dictionary (LSD), containing more than 4500 positive and negative words used to convey sentiment. Unlike the unsupervised clustering techniques used above, the LSD takes a “bag of words” approach to text analysis, counting all instances of positive and negative dictionary entries. A net tone score per article is then constructed by taking the difference in the proportion of positive words and negative words.

To reduce the chance of false attribution of tone, I apply the LSD's pre-processing modules to negate the impact of double negatives, homonyms or other structural or syntax patterns. Theoretically, tone can range from +100 to −100; however, since it is unlikely for a news article to be composed entirely of negative or positive words, the tendency is for net tone to range in the low positive or negative numbers. Though this simple calculation of tone may appear to be a bit simplistic, there is evidence that this measure of tone measures up quite well against human coding (Young and Soroka, Reference Young and Soroka2012). Assessing tone of certain frames, such as illegality, provides an additional challenge, namely, how to account for changes in tone in coverage of a negative topic. Terms associated with these frames are likely to influence the volume of negative coverage—after all, the words “illegal” itself is found in the negative tone dictionary. One way to mitigate the effects of overlap between a frame dictionary and the negative tone dictionary is to remove words or phrases from the negative tone dictionary that are also present in the other dictionaries. This treats words in the individual frame dictionaries as neutral and only takes the surrounding vocabulary as a measure of change.

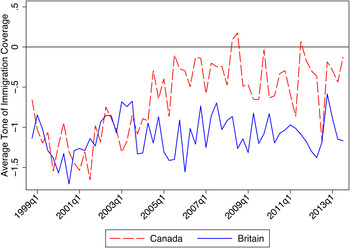

Figure 5 compares aggregate article tone of Canadian and British print news coverage of immigration. The data suggest that, while Canadian news coverage of immigration is generally more positive than its British counterpart, it was markedly less so in the years following 9/11. Given the context, it is possible that particular frames are driving the negative tone of aggregate immigration coverage. Figure 6 looks at the trends associated with average tone scores by frame. To ensure that the tone reported is specific to the actual frames, I use the Lexicoder sentence proximity module, which allows the tone dictionary to measure only the sentences that include a framing term. In other words, this approach centres in on words and phrases specifically used in close proximity to frame cues.

Figure 5 Aggregate Tone of Coverage (Canada and Britain)

Figure 6 Sentence Proximity Tone (Canada and Britain)

Figure 6 confirms the assumption that illegality and refugee frames are driving the downward trend in Canadian framing of immigration. Indeed, it is possible that the negative coverage of these two frames may have had some carryover effects to other frames as social services and diversity frames were also markedly more negative in the period following the 1999 Chinese refugee event and 9/11 than they were from 2004 onwards. This contrasts with the earlier finding that Canadian news framing of immigration is episodic. However, the data also suggest that, while there was little resilience in the content of framing, negative tone was more resilient in the wake of these events. Post-2004, however, there is a positive turn in the tone of immigration framing across all frames. Indeed, framing of social services, economy and labour, and diversity all show an upward trend in the tone of coverage.

The tone of British coverage, by comparison, suggests a generally more negative take on immigration, regardless of which frame is in use. While illegality and refugee framing appear to be the most negative, all five frames consistently cue negative language. Diversity framing takes a particularly negative turn after 2003. This change may be on account of its connection with illegality and refugee framing (recall diversity's strong correlation with these frames), or it could equally be a reflection of media perceptions of the impact of increased ethno-racial diversity on British society. Similarly, 2003 also marks the beginning of an era wherein the number of British immigrants surges above 500,000 per year, suggesting that a heightened rate of immigration may have prompted concern over the amount of diversity in Britain (though see Lawlor, Reference Lawlor2015, for an assessment of the impact of migration numbers on framing).

In sum, Canada and Britain function as a useful set of comparable cases insofar as they share similarities in the frames used in mainstream print media, but present stark differences in the variability of tone of framing. Additionally, correlations among frames suggest that immigration has been framed in ways that are not necessarily competitive; rather, they appear to be quite complementary to one another. There is considerable support for the idea that negative security and refugee framing drives coverage, but there is sufficient variation in tone to conclude that immigration is not always dominated by negative framing of migrants as security threats. Frames that cue considerations around access to social programs and the economic benefits of migration continuously occupy a place in immigration coverage and, in Britain, these considerations appear to be increasing.

Discussion

The focus of this article was to cast a longitudinal gaze on the framing of immigration across two immigrant-receiving countries: Canada and Britain. In doing so, this article articulates a useful way to extract frames from media reports and highlights two of the chief considerations—volume and tone of coverage—for scholars who want to investigate the real-world impact of immigration. Though results are necessarily presented at the aggregate level given the ACA framework used, the implications for future work are manifold.

This study yields several key findings around the content of frames, the volume of their usage and the differences in their application in terms of tone. First, despite substantial differences in immigration levels, the volume and origin of migrants, as well as public opinion, the frames used in immigration coverage are consistent across British and Canadian broadsheet news. Inductive techniques yielded five clear frames that facilitated comparability. While there were subtle differences in the way that dictionary terms clustered together, there was sufficient similarity to further validate a cross-country comparison with empirical evidence.

Second, differences lie in the event-driven framing style typical of Canadian papers and the British media's over-time shift in the use of frames. Whereas Canadian coverage is driven by a focusing event such as a terror attack or a large-scale refugee claim, Britain has seen more durable changes in the volume of framing, particularly in the period surrounding the expansion of the British immigration regime to EU countries. Additionally, framing of the illegality aspects of immigration in British news are being challenged by economically and social services oriented frames, suggesting that immigration is increasingly considered by the media as a multi-faceted domestic policy issue.

This cross-national difference may, in part, be explained by Canada's larger social safety net and Britain's reluctance to provide social benefits to newcomers. Whereas Canada offers a variety of settlement services, including language training, health care and education (Tolley, Reference Tolley, Tolley and Young2011; Tossutti, Reference Tossutti2012), the British government has been adamant in its refusal to provide language training or settlement services for immigrants (Bleich, Reference Bleich2003; Siemiatycki and Triadafilopoulos, Reference Siemiatycki and Triadafilopoulos2010). One might expect the relatively positive Canadian experience with newcomer integration to be the focus of a great deal of news coverage; however, it may be that positive experiences are simply less newsworthy. Additionally, while news coverage of immigration is negative in discussions of refugee and illegality in both countries, it is far more positive when discussions about the economy or social services are queued, suggesting that even in a context such as Britain, where immigration frames are largely characterized negatively, certain frames routinely prompt less negative observations.

Third, findings suggest that even countries that pride themselves on a predominantly positive modern history with immigration should be aware that there remains a strong undercurrent of negative debate in the mainstream news that cannot simply be attributed to those who are “anti-migration.” While casual observers of the two countries’ politics may adhere to the notion that Britain is less tolerant of migration to its shores based on public opinion, Canadians should reflect carefully on how the media frame immigration and the impact they may have on future public opinion. Canadian print media's refugee framing is, on balance, negative. This observation should caution Canadians—political pundits, academics or citizens—making broad claims about the comparative depths of Canadian tolerance. It may be that Canadians assert a different level of acceptance of refugees than they do of immigrants. This is an important distinction particularly in the face of expansion of the refugee acceptance program under the present Conservative government and the maintenance of immigration numbers at roughly the same level in the past 20 years.

Fourth, it is evident that immigration framing is vulnerable to the journalistic and editorial predilection for conflict. It remains that, of the five frames studied here, illegality and refugee framing form the majority of frames in both media environments. Stories of crime and fraud or those referencing the plights of refugees dominate the headlines and, while there is no evidence that immigrants or refugees are more responsible for crime or fraud than other citizens, the volume and tone of these types of frames has the potential to impact perceptions of how immigrants and refugees fit into British and Canadian society. Given the tendencies of broadsheet newspapers to focus on some of the more sensational aspects of immigration, one wonders how framing might play out in the tabloid media. A comparison of broadsheet and tabloid newspapers, particularly in Britain where, as of writing, they make up the top six circulating papers in Britain, would present a valuable companion study.

One final contribution of this paper is the method of identifying and extracting frames using inductive techniques. This approach removes much of the potential bias of researchers selecting frames based only on deductive reasoning (that is, the selection of frames based only in or creating framing dictionaries using terms they favour or have found prevalent in their own research). While it does not represent the only way to reliably extract frames, it does meet the varying criteria set out by scholars in the field (Cappella and Jamieson, Reference Cappella and Jamieson1997; Chong and Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007a), and has the advantage of being useful across framing studies, not only with respect to immigration studies.

With the proliferation of formal and informal international commitments to the acceptance of immigrants and refugees across Western nations, it is expected that Canada and Britain will continue to be among the top immigrant-receiving countries in the world. Consequently, an appreciation of the driving forces behind media's portrayal of migrant groups will provide scholars with the required contextualization to understand the permissiveness or restrictive nature of public policy making. This analysis deepens our understanding of media discourses on immigration and provides insights into the narrative environment within which policy makers operate when addressing issues related to immigration. Future research would do well to link these findings to individual level perceptions on the impact of media intake on perceptions of the place of migrants in society.