Introduction

Multiculturalism is becoming a partisan issue. Both left and right parties face increasing pressures to both support and oppose multiculturalism. The emergence of far-right parties such as the French National Rally and the UK Independence Party has pushed centre-right, and to a lesser extent centre-left, parties to oppose multiculturalism. At the same time, increasingly diverse electorates create an incentive to support multiculturalism. What does this mean for the future of multiculturalism? The Canadian case suggests partisan consensus is important to policy development. A centrist Liberal government announced Canada's first multiculturalism policy in 1971, and a Conservative government passed its first multiculturalism legislation in 1988. If other countries are similar to Canada, increasing partisan division should decrease the likelihood of policy expansion.

This article tests whether the conditions that led to policy expansion in Canada apply to other cases. I find that centre-right support for multiculturalism has a larger impact on policy adoption than centre-left support. Consistent with the Canadian case, I also find that cross-party support is important to increasing the likelihood of policy adoption, while government support on its own has little impact on policy adoption.

Literature Review and Theory

Why look at multiculturalism?

There is a growing literature on the development of immigrant integration policies (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker1992; Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2001; Favell, Reference Favell1998; Fleras and Elliot, Reference Fleras and Elliot2002; Goodman, Reference Goodman2010; Goodman, Reference Goodman2014; Howard, Reference Howard2009; Janoski, Reference Janoski2010; Joppke, Reference Joppke2017; Koopmans et al., Reference Koopmans, Michalowski and Waibel2012; Koopmans et al., Reference Koopmans, Statham, Giugni and Passy2005; Lopez, Reference Lopez2000), but this work tends to either focus on immigration and integration policy in general terms or on single case studies of countries such as Australia or Canada. It is worth taking a closer look at multiculturalism because its requirement that governments support and accommodate cultural difference is particularly controversial. This aspect comes through in debates over niqab, hijab and other bans of religious dress that date back to the 1989 foulard affair in France (Thomas, Reference Thomas2005). Furthermore, the extent to which Australia and Canada may be outliers, as countries with long histories of receiving immigrants, suggests a need to look at policy development across a broad range of countries.

Defining multiculturalism

Much of the existing literature on parties and immigration looks at policy in broad terms. In the literature on parties, there is a tendency to place parties on broad spectrums that include immigration, integration, citizenship policies and sometimes even European integration (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2011; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Krouwel, Reference Krouwel2012; Van der Brug and Van Spanje, Reference Van der Brug and van Spanje2009). This approach is useful for analyses of party systems but can hide important nuances in the way parties affect policy. A left party might, as Givens and Luedtke (Reference Givens and Luedtke2005) find, be open to liberal integration policies as a way of expressing solidarity with immigrants already in the country. It may also oppose liberalizing entrance and citizenship rules to protect working-class supporters from competition for jobs (Hinnfors et al., Reference Hinnfors, Spehar and Bucken-Knapp2012).

To account for the distinctions between different types of policies, I separate multiculturalism from other integration policies. Multiculturalism includes either government recognition of immigrants’ and ethnic minorities’ culture or policies that help immigrants maintain their culture when integrating. This definition fits with a variety of theoretical understandings of such policies articulated by theorists, including Carens (Reference Carens2000), Kymlicka (Reference Kymlicka1995), Parekh (Reference Parekh2006) and Taylor (Reference Taylor, Taylor and Gutmann1994). It also sets multiculturalism apart from other programs that are designed to facilitate integration but which do not support culture. These other programs might include anti-discrimination initiatives, majority-language classes or civic education classes. While multicultural and non-multicultural integration policies are not mutually exclusive, they are not necessarily connected.

Going beyond parties in government

There is a tendency in the existing literature to focus on parties in government. Abu-Chadi (Reference Abou-Chadi2016), Bruenig and Luedtke (Reference Bruenig and Luedtke2008), Givens and Luedtke (Reference Givens and Luedtke2005), Gudbrandsen (Reference Gudbrandsen2010), Howard (Reference Howard2009) and Triadafilopoulos and Zaslove (Reference Triadafilopoulos, Zaslove, Giugni and Passy2006) all examine the way governing parties shape immigration and integration policy. This is understandable. In parliamentary systems, governing parties control the executive, giving them the power to implement policy. If they have a majority or majority coalition, they can pass any legislation needed to adopt a policy. Opposition parties, by contrast, have few ways to influence policy.

Opposition parties, however, should not be ignored. Immigration and integration policies stand out from other policies because, at least until very recently,Footnote 1 the salience of anti-immigrant attitudes depended on the extent to which they were mobilized by political parties (Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup, Reference Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup2008; Koopmans et al., Reference Koopmans, Michalowski and Waibel2012; Odmalm, Reference Odmalm2012; Perlmutter, Reference Perlmutter1996). This tendency is notable given that Lahav's (Reference Lahav2004) work on the politics of immigration in Europe shows that immigration policy tends to have a low level of salience with voters. Opposition parties can hurt pro-multicultural governments by mobilizing the policies’ opponents.

Furthermore, multiculturalism is rarely the main cleavage that distinguishes parties. Rather, it is usually a niche policy that, while it can appeal to immigrant and other minority voters, can also alienate its opponents. In such circumstances, the decisions of opposition parties should matter to how a governing party proceeds. If the opposition decides to make an issue of multiculturalism by opposing it, the governing party should retreat from their commitments in order to prevent the issue from dividing their electoral coalition. If the opposition is supportive, the governing party can follow through on its commitments free from fear of an opposition-mobilized backlash.

Parties and policy development

Political parties play an essential role in the policy process. By controlling the executive and legislature, they often determine which policies will be pursued, whether the laws needed to make policies work will be passed and how policies will be implemented. Much of the literature on agenda setting and policy includes some discussion of how parties advance issues that are important to them. This is shown in the United States by Baumgartner and Jones (Reference Baumgartner and Jones2009) and Kingdon (Reference Kingdon1995) and in Canadian and comparative contexts by Howlett and Ramesh (Reference Howlett and Ramesh2003) and Siu (Reference Siu2014). Work showing parties’ positions influence policy includes Garret's (Reference Garrett1998) work on welfare programs, Hacker and Pierson's (Reference Hacker and Pierson2010) on wealth redistribution in the United States and Araki's (Reference Araki2000) on pensions in Britain.

Parties should matter to the development of multiculturalism, as they do with the development of other types of policies. The next sections, however, will argue that the way multiculturalism cuts across left/right divides and the role of the opposition in mobilizing its opponents make partisan consensus important to policy adoption.

Left and right parties and policy adoption

Support for multiculturalism cuts across left/right divides. Left parties are caught between socially progressive voters who favour multiculturalism and many working-class voters who oppose it. Conversely, right parties are caught between business interests who may want an immigrant-friendly country (and resulting larger labour force) and nationalists (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). As a result, both face difficult strategic dilemmas when deciding about whether to follow through on whatever commitments to multiculturalism they make.

Some right parties may even see multiculturalism as a way to convince fiscally or socially conservative immigrants that they are not hostile to them, as a way of winning their votes. The presence of more conservative-minded immigrants in a number of countries suggests the potential for centre-right parties to make inroads with immigrant voters. Ireland (Reference Ireland2004) finds that in Germany, a substantial number of more conservative Turkish immigrants were sympathetic to the Christian Democrats (though the Christian Democratic Union did little to take advantage of this). Ireland also shows that the Dutch Christian Democrats made appeals to and won over Turkish immigrants in Rotterdam in the mid-1980s. None of this is to say that centre-right parties will necessarily try to win over immigrants; rather, it is to show that there are times when centre-right parties will try to appeal to multiculturalism's advocates instead of its opponents. Thus, paying attention to whether a centre-right party decides to support or oppose multiculturalism is important.

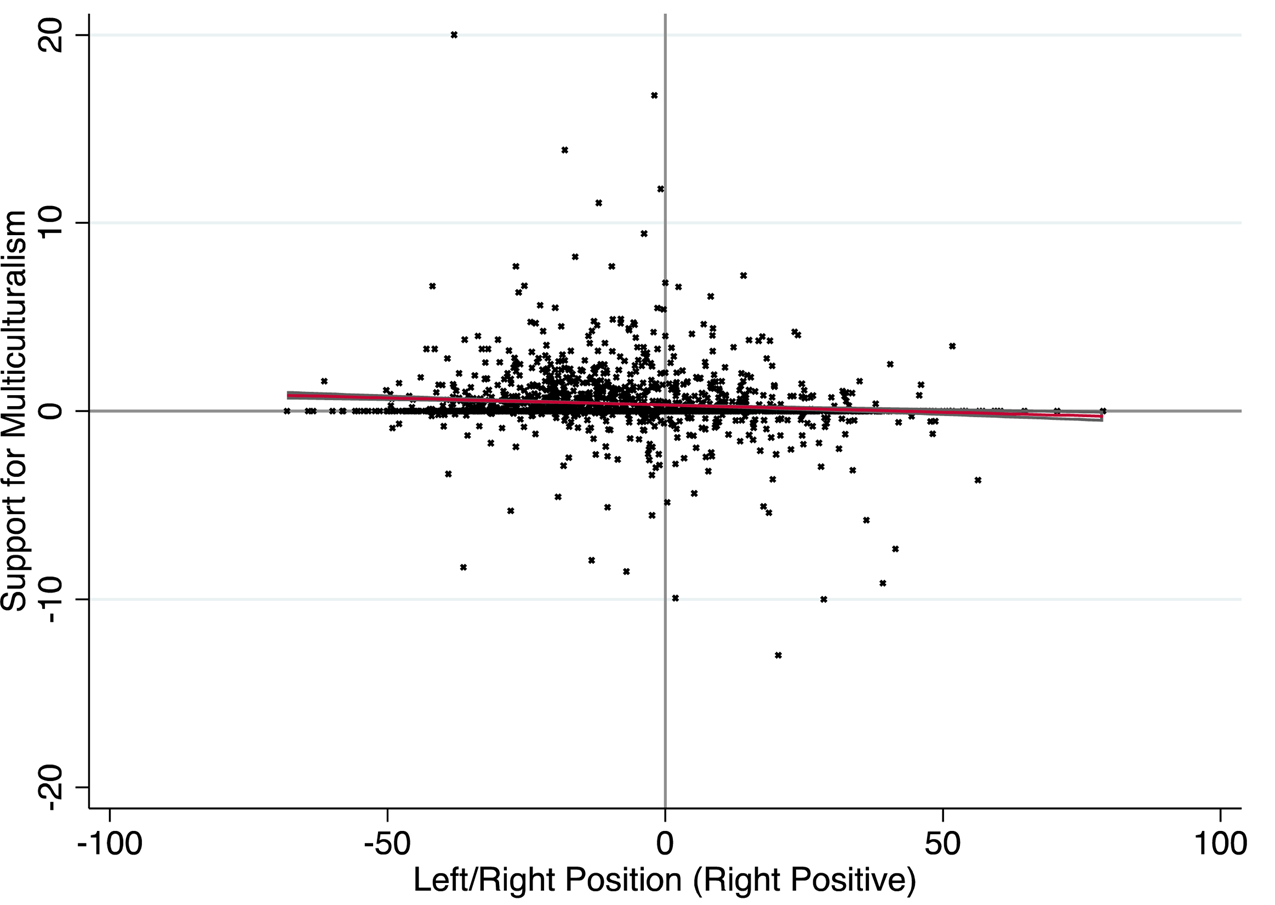

My own analysis also finds that multiculturalism does not fit neatly within the left/right spectrum. Figure 1 shows the relationship between left/right ideology and multiculturalism in Manifesto Project data across 21 industrialized countries going back to 1970. While the downward-sloping line suggest right parties are less supportive of multiculturalism, the cluster of x’s showing each party's position suggests quite substantial variation on both the left and right. There are left parties that oppose multiculturalism (in the bottom left quadrant) and right parties that support it (in the upper right quadrant).

Figure 1 Party Support for Multiculturalism Compared to Left/Right Position

Instances of policy adoption also cross the left/right divide. My analysis of the Banting and Kymlicka Multiculturalism Policy Index finds 46 policies were adopted when left parties were in power, while 32.5 were adopted when right parties were in power. Though more policies have been adopted by left governments than right ones, policy adoption is not limited to cases where left governments are in power.

While I do not look at why left and right parties support multiculturalism, I am interested in whether they follow through on their commitments. Once in office, parties may choose to deliver on their promises or retreat from them. If parties feel that following through on a commitment will hurt them in future elections, they should retreat from it. This should particularly be the case with multiculturalism, given that it is rarely a central plank of a party's platform.

Paradoxically, I expect right parties’ positions to have a greater influence over whether a government decides to follow through or retreat from a promise to adopt multiculturalism. This is because I expect left parties to feel greater pressure to retreat from multiculturalism when right parties oppose it and to follow through with their commitments when right parties support it. The decision of the right party to either support or oppose multiculturalism thus becomes critical to other parties’ behaviour.

Left parties tend to have greater support among immigrants and minority voters. This is in part because of their commitments to support low-income voters (immigrants and ethnic minorities tend to have disproportionately low incomes) and because of their commitments to social solidarity (Bird et al., Reference Bird, Tiberj, Saalfeld, Michon, Tillie, Jacobs, Delwit, Tahvilzadeh, Bergh, Bjørklund, Mikkelsen, Wüst, Jenny, Pérez-Nievas, Bird, Saalfeld and Wüst2011; Dancygier, Reference Dancygier2010; Dancygier and Saunders, Reference Dancygier and Saunders2016). This support should ensure that left parties face pressure to go along with right parties when right parties support multiculturalism, regardless of the position the left party took in the previous election. At the same time, because left parties are often holding together coalitions of multicultural advocates and working-class opponents of multiculturalism, they should face pressure to retreat from multiculturalism when right parties oppose it. In such circumstances, right parties threaten to split left parties’ voter coalitions, and left parties should try to downplay the issue and avoid enacting any policies in response.

The opposite is the case for right parties. When a right party in government opposes multiculturalism, it faces no pressure to enact policies and so there should be no policy expansion. If the right party decides to support multiculturalism and then wins government, it faces strong incentives to follow through on its commitment. It is likely that when right parties decide to support multiculturalism, they are making some attempt to win over ethnic minority voters. The decision to support multiculturalism is an indication that a right party has decided to reach out to minorities instead of appeasing anti-immigrant voters. Because right parties tend to have neither the same history of support among ethnic minorities and immigrants nor as many other issues they can use to appeal to immigrants, multiculturalism becomes a test of these parties’ commitment to protecting immigrants and ethnic minorities’ interests. If they break a promise of multiculturalism, they risk cementing their image as hostile to immigrants and ethnic minorities and undermining the effort to win over such voters that led them to support multiculturalism in the first place.

It is important to note that this argument means that right parties’ positions should influence policy even when those parties are in opposition. An opposition-right party that supports multiculturalism increases the potential that some ethnic minorities will move their support from the left party to the right. This gives the left party a stronger incentive to follow through on their support of multiculturalism. Indeed, there is evidence from both the UK (Dancygier, Reference Dancygier2010) and the United States (Bartels, Reference Bartels and Geer1998; Leighley, Reference Leighley2001) that shows that left parties are more responsive to ethnic minorities’ concerns when they face competition for their votes.

Following this logic, right-party positions have the potential to influence policy in four ways. In-government right parties can either follow through on their support for multiculturalism by adopting policies or follow through on their opposition to multiculturalism by not adopting or removing policies (though, as will be shown in the methods section and related appendices, retrenchment is rare). If a right party in opposition supports multiculturalism, the right party's support gives a pro-multicultural left party some assurance that the right party will not mobilize a backlash and possibly threaten to take pro-multicultural votes from the left party if it does not follow through with its commitments. If a right party in opposition opposes multiculturalism, the threat that it can split the left's voter coalition gives the left party an incentive not to follow through on its support of multiculturalism.

H1: Right-party support for multiculturalism should have a greater impact on policy development than left-party support.

H2: Mainstream right support for multiculturalism should increase the likelihood of policy adoption even when mainstream right parties are in opposition.

Partisan consensus and policy development

The idea that multiculturalism is different from other kinds of policy areas, such as welfare policy, is crucial to my argument. For most policies, parties should try to follow through on their commitments as a way of delivering on their promises. I argue that multiculturalism is different.

Two things lead to this conclusion. First, multiculturalism, like most immigration policies, has concentrated benefits and diffuse costs. Immigrants and ethnic minorities stand to benefit from policies such as those that make it easier for them to enter the workforce while wearing religious dress, that provide support for ethnic minority community organizations and that provide support for mother-tongue language education. These policies tend to impose limited costs (if they impose any at all) that can be spread across society, so the cost to any one individual is negligible. Thus, immigrants and ethnic minorities have a strong incentive to push for multiculturalism policies, and the rest of society has little incentive to resist them. Freeman (Reference Freeman and Messina2002) applies this logic to immigration policy more broadly to explain why most countries have more open immigration policies than public opinion supports.

If this were the only way in which multiculturalism was unique, then one would simply expect high levels of policy adoption and low levels of retrenchment. Multiculturalism is also unique, though, in that political parties opposed to it can play a role in mobilizing a backlash among voters who may otherwise prioritize other issues. This has been demonstrated in the UK by Bale (Reference Bale2014) in his work showing that the Conservatives were able to take votes from Labour by mobilizing opponents of liberal immigration and integration policies. It has also been shown in Europe by a number of studies on multiculturalism and immigration policy (Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup, Reference Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup2008; Koopmans et al., Reference Koopmans, Michalowski and Waibel2012; Odmalm, Reference Odmalm2012; Perlmutter, Reference Perlmutter1996). The political costs of bringing in a multiculturalism policy are thus dependent on what the opposition party does. If the opposition supports multiculturalism, the cost is low. If the opposition opposes multiculturalism and successfully mobilizes anti-multicultural voters, the cost can be high.

The implication of this is that policy adoption should require the support of both the government and the opposition regardless of whether the government is a left, right or centre party. To show this, it is not sufficient to demonstrate that cross-party support increases the likelihood of policy adoption. If opposition positions matter to policy adoption, government positions on their own should have little effect on policy. Thus, this theory produces the following two hypotheses:

H3: The greater the cross-party support for multiculturalism, the greater the likelihood of policy should be.

H4: Government support for multiculturalism on its own should have little impact on policy adoption.

Data and Methods

Measuring policy adoption

I have expanded the Banting and Kymlicka Multiculturalism Policy Index to measure policy adoption in different countries. The original index includes scores for just three years: 1980, 2000 and 2010. The gaps between years make it difficult to determine which parties were in power and where they stood on multiculturalism when any given policy was adopted. To deal with this issue, I created a new, annualized index that includes every year from 1960 to 2011. I extended the index back to 1960 to include policy adoption that occurred prior to 1980 in countries such as Canada. In doing this, I was as faithful to the original index as possible and used the same indicators (noted in Appendix A). I used the evidence in the original index (in Tolley, Reference Tolley2011) as a starting point to identify the exact years in which policies were adopted, I checked for similar policies and I checked for any policy retrenchment. Countries’ scores, as well as justifications for these scores, can be found at https://www.queensu.ca/mcp/annual_data (Westlake, Reference Westlake2017).Footnote 2

Duyvendak et al. (Reference Duyvendak, van Reekum, El-Hajjari and Bertossi2013) and Wright and Bloemraad (Reference Wright and Bloemraad2012) raise questions about whether dual citizenship, affirmative action and mother-tongue education are multiculturalism policies. To account for this, I run tests excluding these policies in Appendices G, H and I. They do not produce substantially different results from the ones presented here.

Measuring parties’ positions

I use Manifesto Project data to measure parties’ positions. The Manifesto Project scores parties on a variety of issues based on the proportion of their manifesto that parties devote to each issue. The data include scores for positive and negative mentions of multiculturalism and positive and negative mentions of the national way of life. Negative mentions of multiculturalism can be subtracted from positive mentions to create a score for a party's support for multiculturalism, and the same can be done with respect to national way of life to create a score for nationalism.

I use both scores in my analysis. The Manifesto Project scores match my definition of multiculturalism well, in that they use commitments to supporting cultural diversity as a way of coding support and opposition to multiculturalism instead of just looking for the word multiculturalism. The latter approach to scoring positions is problematic because of the way that the term can be understood differently in different countries and contexts. The Manifesto Project, however, conflates multiculturalism and nationalism in a way that can treat support for national minority groups as support for multiculturalism. This is problematic. I account for this by excluding regionalist, separatist and far-right parties from my analysis, as these parties are most likely to have their scores affected by the problems in the Manifesto Project's coding scheme. I also use two measures for support for multiculturalism, one that uses multiculturalism scores only and one that includes nationalism scores by subtracting support for nationalism from support for multiculturalism. The former scores provide a narrower measure for multiculturalism, while the latter reduce the noise in the data caused by the conflation of multiculturalism and nationalism. A fuller discussion of the way multiculturalism is coded in the Manifesto Project and the issues resulting from it is included in Appendix B.

To compare party positions across countries as they evolve over time, I combine the positions of multiple parties to create scores for each country in each year observed. The scores calculated are averages weighted by the number of seats a party has in the lower house of parliament. This accounts for the influence the party has over the policy process. I calculate four averages for each country in each year: one for all parties except regionalist, separatist and far-right parties (referred to as a cross-party score); one for parties in government; one for left parties; and one for right parties.Footnote 3

Multiculturalism policies are not always adopted in election years, yet parties only release manifestos during elections. As a result, I have to estimate party positions in non-election years. To do this, I calculate a linear trend from one election to another for each party. I prefer this approach to using the most recent prior election because it accounts for the way that party positions change over time. For policies adopted late during a government's time in office, the upcoming election is likely a better reflection of their position than an election that may have occurred three years prior.

Control variables, survival analysis and descriptive statistics

I use a mix of survival analysis and descriptive statistics. I use Cox proportional hazard models in place of ordinary least squares (OLS) models for two reasons. The first is that the number of policies a country can adopt is limited. Once a country has reached the maximum number of policies in the index, it cannot adopt any more. An OLS regression would treat instances when parties supported multiculturalism yet no policies could be adopted as evidence of a lack of a link between party positions and policy adoption. In actuality, policy adoption does not occur in these observations because there are no more policies to adopt. The second reason to use Cox proportional hazard models is that policy retrenchment is rare. Banting and Kymlicka (Reference Banting and Kymlicka2013) and Appendix C demonstrate this. Most cases of retrenchment are limited to the Netherlands. This means that even if partisan support for multiculturalism declines in a country, there will likely be little decline in the number of policies. An OLS model would treat this as a lack of link between parties' positions and policy, when the lack of change is likely a function of the difficulties involved with policy retrenchment.

It is important that governments do not decide every year how many multiculturalism policies they will have in the same way that they might decide how much they want to fund healthcare or education. A government that neither supports nor opposes multiculturalism may decide to keep a large number of existing policies in place not because of a preference for those policies but out of a desire not to change the status quo in an area it has little interest in. An OLS model would treat this as evidence of a lack of a link between parties and policies when it is just evidence of the inertia of existing policies. I am interested in what causes a particular event to happen—a multicultural policy to be adopted—and Cox proportional hazard models are better suited to modelling the likelihood of an event occurring than are OLS models.

To account for the possibility of multiple instances of policy adoption, I have each country re-enter the model after a policy is adopted until it has reached the maximum possible policies in any set of analyses. To account for any relationship between the standard errors in different observations from the same country, I cluster standard errors by country.

I use a number of control variables in my analysis. The first two, the presence of a far-right party and ethnic minority electoral strength, account for competing electoral pressures governments face to either follow through or abandon commitments to multiculturalism. I also control for the impact the ideology of the government has on policy adoption by including a variable for whether the governing party or parties have a left-wing Manifesto Project score. To get at the institutional factors that might prevent a party from following through with its commitments, I control for the presence of a federal system of government and the legislative veto points governments face. As an additional check on the robustness of my results to the ability of the opposition to use institutional veto points to block policy, I run analyses that exclude Switzerland and the United States since these are the two cases where institutions make it easiest for the opposition to block legislation.Footnote 4 These analyses are included in Appendix F and show similar results to those presented here. I account for the hesitancy governments might have to introduce new programs during a weak economy by controlling for gross domestic product (GDP) growth. I also control for feedback loops that may be created by the early adoption of multiculturalism policies by including a variable for the number of other multicultural policies a country has in place during each year observed. A discussion of the measurement of each of these variables, as well as the absence of a control for public opinion, is included in Appendix D.

The baseline hazards for policy adoption differ between settler and non-settler countries. To account for this, I stratify the data based on whether a country is a settler country or not. Further justification of this is included in Appendix D. I do not have a separate control for year, as the time to policy adoption is built into the hazard model and would covary with any control variable for year.

For ease of interpretation, I report hazard ratios instead of coefficients. A ratio of 1 means that a 1-point change in the explanatory variable has no effect on the likelihood of policy adoption. A ratio of 2 means that a 1-point change in the explanatory variable doubles the likelihood of policy adoption, and a ratio of 0.5 means that a 1-point change in the explanatory variable cuts the likelihood of policy adoption in half. To save space, and because adding controls variables has little impact on the hazard ratios for the main variables of interest, I only report models with all control variables in the main body of the text, with models using fewer controls included in Appendix E.

Analysis and Results

Left and right positions and policy adoption

Analysis of the positions of left and right parties and policy adoption produces mixed results. Table 1 shows only a limited effect of right parties’ positions on policy adoption when only multiculturalism positions are looked at. The likelihood of policy adoption increases by 14 per cent for every 1-point increase in right-party support for multiculturalism, but this effect is only statistically significant at the 90 per cent confidence level. Appendix E further shows that this result is not statistically significant when fewer control variables are used, so one should treat this result with a fair amount of skepticism. The same model, however, shows that right parties that are more nationalistic decrease the likelihood of policy adoption. A 1-point increase in right-party nationalism makes a country only 65 per cent as likely to adopt a policy as it would have been had the right party not been as nationalistic. Right-party positions do have a significant impact on policy adoption when one considers their multiculturalism and nationalism positions combined. Either an increase in support for multiculturalism by 1 or decline in support for nationalism by 1 (or some combination of the two) increases the likelihood of policy adoption by 24 per cent. This result is statistically significant and is robust to models with fewer control variables.

Table 1 Left-Party and Right-Party Effects on Policy Adoption

***p > 0.01, **p > 0.05, *p > 0.10

Coefficients are hazard ratios for Cox proportional hazard models.

A coefficient greater than 1 indicates a positive effect; a coefficient less than 1 indicates a negative effect.

Range of effects for a 95% confidence level is shown in parentheses.

As expected, Table 1 shows that the effects of left-party positions on policy adoption are negligible. While Appendix E shows some fluctuation in left-party effects, they are never statistically significant. When one looks at multiculturalism and nationalism positions combined, the relationship has the wrong direction, with left-party support for multiculturalism decreasing the likelihood of policy adoption (though this relationship is negligible and not statistically significant).

All of this provides moderate support for my first hypothesis, that right-party positions will have a greater impact on policy adoption than left-party support. There is a clear link between right-party positions and policy adoption, though lack of right-party support for nationalism seems to matter more than support for multiculturalism. This may mean that right parties’ decisions not to take positions mobilizing anti-multicultural voters may do more to drive policy adoption than attempts by right parties to use multiculturalism to win policy supporters away from left parties. Without clear evidence that left-party positions either increase or decrease the likelihood of policy adoption, it is harder to say whether right parties matter more than left parties. The range of values for the 95 per cent confidence level for the effect of right-party multiculturalism/nationalism positions is just outside the range for left parties, giving some indication that right positions may matter more than left ones.

Right-party positions when left parties are in government

Analysis of right parties’ impacts on policy when left parties are in power shows that they matter even when the left is in office. Table 2 shows that both right positions on multiculturalism only and combined multiculturalism and nationalism positions have a positive impact on the likelihood of policy adoption. Appendix E shows, however, that only the impact of combined multiculturalism and nationalism positions holds consistently regardless of which control variables are included in the model. Each 1-point increase in support for multiculturalism or opposition to nationalism by a right party in opposition increases the likelihood of policy adoption by 30 per cent. Again, absence of right support for nationalism seems to have the larger impact on policy, suggesting that the decision by right parties not to mobilize a backlash has a larger effect than any attempts to compete with left parties for supporters of multiculturalism.

Table 2 Right-Party Impact on Policy Adoption When Left Parties Are in Power

***p > 0.01, **p > 0.05, *p > 0.10

Coefficients are hazard ratios for Cox proportional hazard models.

A coefficient greater than 1 indicates a positive effect; a coefficient less than 1 indicates a negative effect.

Range of effects for a 95% confidence level is shown in parentheses.

These findings support hypothesis 2: that right-party positions should matter even when they are in opposition. Indeed, the impact that right-party positions have over policy are not much different when right parties are in opposition than the impact that they have in all situations. Crucially, these results hold up when one controls for institutional constraints on governments’ actions and, as shown in Appendix F, when Switzerland and the United States are removed from the analysis. This suggests that right parties’ influence in opposition is not simply a matter of their ability to use institutional veto points to check governments and that the threat that right parties may mobilize an anti-multicultural backlash matters to policy development.

Cross-party and government positions

There is some support for my theory that both government and opposition support are necessary for policy adoption. None of the models in Table 3 show a statistically significant relationship between government support and policy adoption. This result is robust to models with fewer control variables. Indeed, the only model that shows government positions on their own increasing the likelihood of policy adoption combines multiculturalism and nationalism scores and excludes cross-party positions. The 5 per cent increase in that likelihood is small and not statistically significant.

Table 3 Cross-Party and Government Effects on Policy Adoption

***p > 0.01, **p > 0.05, *p > 0.10

Coefficients are hazard ratios for Cox proportional hazard models.

A coefficient greater than 1 indicates a positive effect; a coefficient less than 1 indicates a negative effect.

Range of effects for a 95% confidence level is shown in parentheses.

In contrast, there is a fair amount of evidence that cross-party support influences policy adoption. Both models that include cross-party positions show a positive relationship, with the model that includes only multiculturalism being statistically significant at the 95 per cent confidence level and the model that includes both multiculturalism and nationalism positions being statistically significant at the 90 per cent confidence level. It should further be noted that Appendix E shows that models with fewer control variables for both measures produce positive effects for cross-party positions that are statistically significant at the 95 per cent confidence level. These effects are also quite substantial. When one looks at multiculturalism positions only, a 1-point increase in cross-party support increases the likelihood of policy adoption by 53 per cent. For both multiculturalism and nationalism positions, the increase in the likelihood of policy adoption drops a bit to 39 per cent.

These results fit with both hypotheses 3 and 4. In line with hypothesis 3, I find that cross-party support increases the likelihood of multicultural policy adoption. Importantly, my results match my expectations in hypothesis 4: that government support for multiculturalism on its own has little influence over policy development. That there is evidence for both is important to my theory. These analyses suggest that more is going on here than policies that have broad cross-partisan support being adopted. Rather, a broad partisan consensus in support of multiculturalism is a prerequisite to increasing the likelihood of policy adoption; government support on its own is not enough to do so.

As with the analysis on right parties in opposition, the importance of electoral incentives can be underlined by the robustness of this result to controls for institutional checks on government. The results presented in Table 3 hold when I include a control for constraints on government. They also hold up when I remove Switzerland and the United States from the analysis, as shown in Appendix F.

Descriptive statistics and cross-party consensus

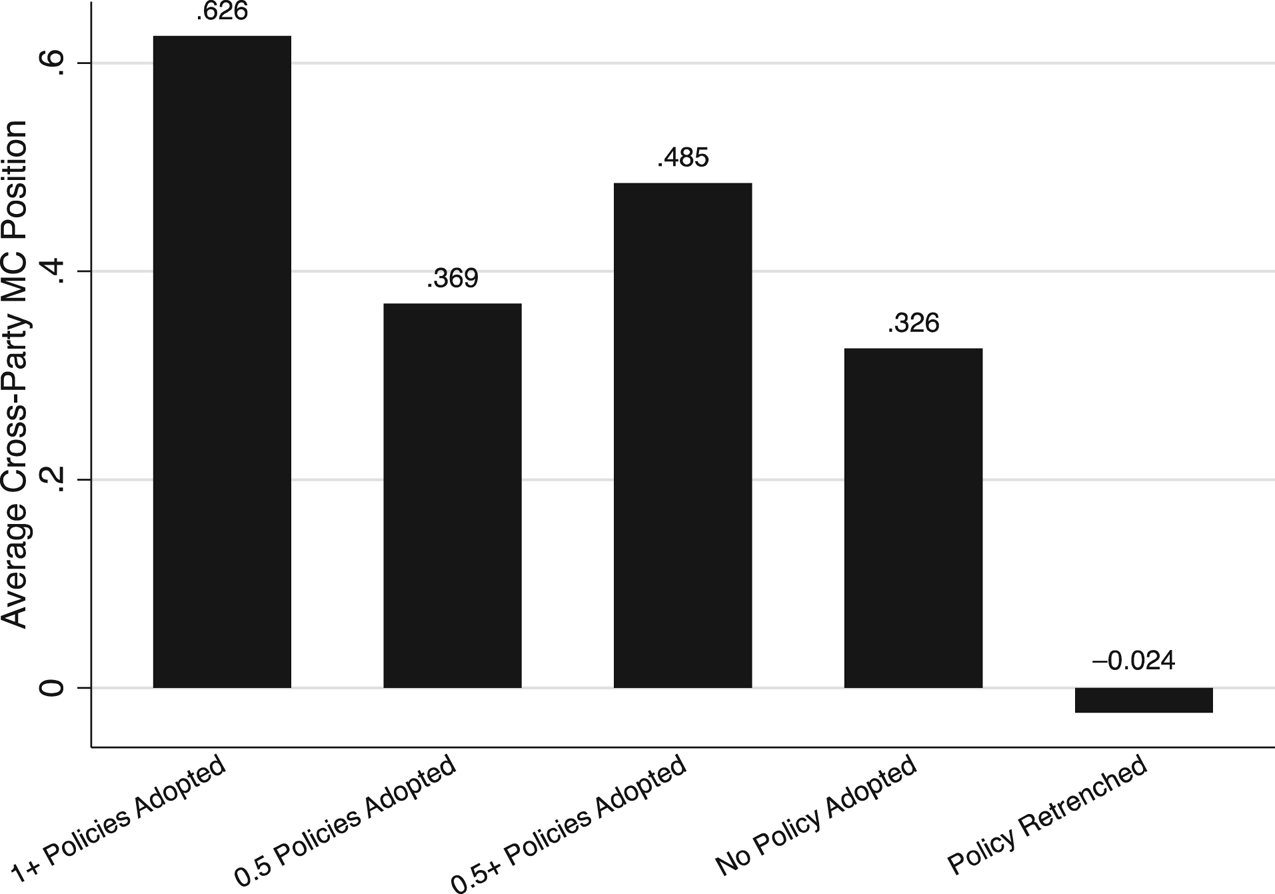

Descriptive statistics largely support the importance of cross-party consensus to policy adoption. Figure 2 shows that average cross-party support for multiculturalism is 0.626 points when at least one policy is adopted and 0.485 points when at least a partial policy is adopted. This compares to 0.326 points when no policy is adopted. Cross-partisan support for multiculturalism when a government adopts at least one policy is almost twice as high as it is when no policy is adopted. Unsurprisingly, cross-partisan support is lowest in the few cases where there is policy retrenchment, with average support being −0.024 points. One has to be careful not to read too much into the low level of cross-party support when there is retrenchment because there are only 10 observations in that category.

Figure 2 Cross-Party Positions When Policies Are Adopted

Figure 3 further shows that most policies are adopted when either left and right parties agree on multiculturalism or when one party supports the policy and the other takes no position. Of the 72.5 instances of policy adoption in my analysis, 36.5 take place when there is cross-partisan consensus in favour of multiculturalism. Another 11 take place when either the left or right supports multiculturalism and the other party does not take a position; 14.5 take place when no party takes a position. Only 10 instances of policy adoption occur when there is conflict between left and right parties over multiculturalism, with 9 of those being instances of left support and right opposition. The fact that 66 per cent of cases of policy adoption occur when there is no left/right conflict over the policy (and at least one party supports multiculturalism), compared to 15 per cent when there is conflict, highlights the importance of cross-party consensus to the development of multiculturalism.

Figure 3 Left and Right Consensus and Policy Adoption

Conclusion

Both support by parties on the right and cross-party support for multiculturalism are important factors in explaining policy adoption. My results show that the decision by right parties about whether to support multiculturalism has a clear impact on policy. I also show that government party support on its own does little to increase the likelihood of policy adoption; cross-party support is necessary to see such an increase. That these results are robust to controls for the institutional constraints that governments face suggests that opposition parties can dissuade governments from following through on their commitments to multiculturalism by mobilizing an anti-multicultural backlash.

The importance of right parties to policy adoption suggests that scholars should not just look at left parties when explaining policy adoption. Right parties’ decisions to either support or oppose multiculturalism make a difference by affecting whether a governing party will be threatened by an anti-multicultural backlash. This gives right parties a unique influence over multiculturalism, even if left parties tend to be the parties that are more supportive of it.

These findings have important implications for the future of policy development. As far-right parties get stronger, they tend to push centre-right parties toward opposing multiculturalism and toward becoming more nationalistic. This decreasing centre-right support makes policy adoption less likely. As cases like Canada—where parties from across the political spectrum support multiculturalism—become more rare, so too will the likelihood of policy expansion.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423919001021.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to all those that have commented on this work at various stages of its development. Included in this group are my PhD dissertation committee, Richard Johnston, Antje Ellermann and Andrew Owen, and examiners Barbara Arneil, Phil Triadafilopoulos and Rima Wilkes. I also received valuable advice or comments from Anjali Thomas Bohlken, Christopher Kam, Clare McGovern, Benjamin Moffitt, Elizabeth Schwartz and the anonymous reviewers.