Introduction

Voter turnout has declined in several countries. A lower turnout is problematic as it may lead to an unequal representation of citizens’ preferences in politics (Dassonneville and Hooghe, Reference Dassonneville and Hooghe2017). Many scholars have, for this reason, investigated what explains citizens’ electoral participation. They have found that the decision to vote in elections is strongly determined by a sense of duty (Smets and van Ham, Reference Smets and van Ham2013; Blais, Reference Blais2000; Blais et al., Reference Blais, Young and Lapp2000; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2004); that is, individuals who feel a sense of duty are much more likely to vote than their counterparts. Where this attitude comes from remains an open question, however. Following the lead of scholarship that has found a relation between civic education and duty-related attitudes (Dassonneville et al., Reference Dassonneville, Quintelier, Hooghe and Claes2012; Pasek et al., Reference Pasek, Feldman, Romer and Jamieson2008) and especially the work of Carol Galais (Reference Galais2018), this article assesses whether civic education can help to spur a sense of duty.

Although Galais's study provides the first empirical evidence of how civic education can contribute to the development of civic duty—and thus, where this attitude comes from—her study misses some important mechanisms through which school socialization may occur (for example, civics courses and open classroom environment).Footnote 1 As a consequence, we not only have a limited understanding of what drives civic duty to vote but also don't know the relative impact of different forms of civic education on citizens’ sense of duty. (For the importance of a comprehensive approach to the study of civic education, see the work of Stadelmann-Steffen and Sulzer, Reference Stadelmann-Steffen and Sulzer2018.Footnote 2)

Following good practices in socialization studies (see, for example, Milner, 2008), I conduct a systematic cross-country analysis of the link between different forms of civic education— civics courses, active learning strategies and open classroom environment—and civic duty. To this end, I use the pooled data from the most comprehensive study of adolescents’ experience with different forms of civic education: the 2016 International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS; International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, 2016).

My analyses suggest that these different forms of civic education are all correlated with civic duty but that civics courses are by far the most influential civic duty determinant. The results are confirmed in subsequent country-specific analyses: while civics courses are significantly correlated with civic duty in a majority (61%) of the countries in the data, active learning strategies are so in less than a tenth (9%), and open classroom environment are so in slightly more than a third (39%) of the countries. By providing such empirical evidence, this study elucidates the means through which schools can spur a sense of duty and also suggests the relative effect of each mechanism of school socialization on civic duty.

The article is organized as follows: First, I discuss the theoretical relation between civic education and civic duty and identify the hypothesized mechanisms connecting the two. Next, I present the 2016 ICCS data, as well as the measures of the dependent and independent variables. In the subsequent three sections, I present the methodology, the main results and the results from supplementary tests. I conclude with a discussion of the main findings and what we can learn from them.

Civic Education and Sense of Civic Duty to Vote

Civic education likely helps to develop civic duty among individuals. Outside the political science literature, one can indeed find indications that active learning strategies can foster a sense of duty. For example, several studies have demonstrated that hands-on experiences with politics—whether through a legislative advocacy day (Beimers, Reference Beimers2016), an engagement with local civil-society organizations (Turner, Reference Turner2014) or extracurricular political activities in college (Simmons and Lilly, Reference Simmons and Lilly2010)—can foster civic skills, which in turn may lead to a sense of duty to vote. In addition to these studies, Huerta and Jozwiak (Reference Huerta and Jozwiak2008) have shown that the introduction of the New York Times as class material can yield an improvement in students’ attitudes toward community involvement, which may affect a sense of duty. In short, a review of the literature suggests a link between active learning strategies and civic duty.

Other studies suggest that open classroom environment and civics courses may be as effective as active learning strategies in forming “good citizens.” The fact that civic education can promote duty-related attitudes points in this direction. For example, using data from the Belgian Political Panel Survey (BPPS), Dassonneville et al. (Reference Dassonneville, Quintelier, Hooghe and Claes2012) have shown that experience with an open classroom environment can lead to a sense of political trust. The authors have also shown that learning about politics in a formal setting can foster an interest in political affairs. “Dutiful” citizens (those for whom voting in elections is a duty) are likely to trust the political system and politicians and to be very interested in political affairs (Galais and Blais, Reference Galais and Blais2017; Carreras, Reference Carreras2018). Consequently, it seems plausible to assume a link between open classroom environment and civics courses and a sense of civic duty.

In the civic duty literature, Galais's (Reference Galais2018) study, published in the Canadian Journal of Political Science, was the first exploration of the link between civic education and civic duty. Starting from the extensive evidence that civic education contributes to the development of a range of political attitudes (Dassonneville et al., Reference Dassonneville, Quintelier, Hooghe and Claes2012; Pasek et al., Reference Pasek, Feldman, Romer and Jamieson2008), Galais sought to clarify whether civic education also affects civic duty. In this way, she aimed to gain a better understanding of the origins of civic duty, which is a key determinant of turnout (Blais, Reference Blais2000; Blais et al., Reference Blais, Young and Lapp2000; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2004; Riker and Ordeshook, Reference Riker and Ordeshook1968).

Why should we expect a connection between civic education and civic duty? Referring to the social reproduction theory, Galais defends the idea that the school serves as an incubator of social norms to new generations of citizens (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu, Karabel and Halsey1977; Dennis, Reference Dennis1968); that is, through the school, individuals learn how to behave socially. Given that voting still constitutes a key social norm in most democracies (Bolzendahl and Coffé, Reference Bolzendahl and Coffé2013), it is quite likely that civic education will transmit this norm and consequently foster an attitude of civic duty among adolescents.

Galais argues that, in addition to contributing to a process of social reproduction, schools can instil civic duty in more indirect ways. More specifically, she argues that schools may engender a sense of civic duty by conveying that it is important to take an active role in the democratic process and that people in a given community must fulfil their social obligations for the sake of a greater good (see Flanagan et al., Reference Flanagan, Bowes, Jonsson, Csapo and Sheblanova1998; Torney-Purta et al., Reference Torney-Purta, Lehmann, Oswald and Schulz2001; Mosher et al., Reference Mosher, Kenny and Garrod1994; Pasek et al., Reference Pasek, Feldman, Romer and Jamieson2008). Furthermore, schools may foster a sense of duty by cultivating a language of duties and a sense of community attachment (see Macaluso and Wanat, Reference Macaluso and Wanat1979; Burtonwood, Reference Burtonwood2003; MacMullen, Reference MacMullen2004).

To prove a relation between civic education and civic duty empirically, Galais explores the data from the 1994–2008 Canadian National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY). Her multivariate logistic regressions focus on the effect of democratic governance on youngsters’ sense of duty. Her findings are encouraging, as they suggest a significant correlation between civic education (specifically, democratic governanceFootnote 3) and civic duty. However, whether these findings are present for different forms of civic education remains an important question that no study has since explored with a more comprehensive dataset. This article performs this role by conducting a systematic cross-country analysis of the effect of civics courses, active learning strategies and open classroom environment on civic duty.

Data and Measures

To test whether the connection between civic education and civic duty is present for different forms of civic education, I rely on the pooled data from the 2016 International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS). To my knowledge, the 2016 ICCS represents the most comprehensive study of adolescents’ exposure to different forms of civic education. I make use of the comparative nature of the 2016 ICCS—it interviewed 86,914 eighth-graders from 3,671 schools in 23 countries—to gain an even greater understanding of whether different forms of civic education affect civic duty, by observing the number of countries in which a relation between each form of civic education and civic duty is present. (See Appendix 1 for a list of countries and for the number of respondents and schools in each of them.Footnote 4)

To test appropriately the link between different forms of civic education and civic duty, it is key that the dependent variable (civic duty) is well measured. The civic duty question in the 2016 ICCS dataset—“For you, how important are the following behaviors for being a good adult citizen? Voting in every national election”—seems to fulfil this requirement, as the distribution of respondents (for 82%, voting is a duty; for 18%, voting is not a duty) resembles the distribution reported in other studies (see, for example, Bowler and Donovan, Reference Bowler and Donovan2013; Weinschenk, Reference Weinschenk2014). It is also reassuring that previous work has relied on a similar type of civic duty measure (see, for example, Dalton, Reference Dalton2008; Klemmensen et al., Reference Klemmensen, Hatemi, Hobolt, Petersen, Skytthe and Nørgaard2012; Marien et al., Reference Marien, Hooghe and Quintelier2010). (See Appendix 2 for mean, standard deviation, maximum and minimum values, number of valid responses of civic duty and of all other variables in the analyses.)

As for the main independent variables, the 2016 ICCS measures different forms of civic education in a comprehensive and methodologically rigorous way by employing a total of 3 questions and 19 survey items. One question taps into what extent students were taught seven different civics topics in class. Another question measures whether students performed six different political activities in school, in the last 12 months. Yet another question captures students’ experience with six different aspects of an open classroom environment. (See Appendix 3 for the three civic education questions and their corresponding items.)

Civic education is hence measured in the 2016 ICCS in a rigorous way by means of multiple items. Importantly, the high internal reliability—0.81, 0.68, and 0.78—between the items in each question means that they are internally coherent and that they indeed capture a single form of civic education. Because reducing these data to a unidimensional measure of different forms of civic education is needed, I perform three principal component analyses (PCAs) to each question. A single eigenvalue crossing the 1.00 threshold is obtained, leading to the formation of the “learning,” the “participation” and the “openness” indexes.Footnote 5

Relying on these indexes may be problematic, however, if some students in the data overestimate or underestimate their experience with civic education and if some students report an experience with civic education because of an a priori sense of civic duty to vote. Fortunately, the 2016 ICCS provides information on respondents’ school, which may be used to aggregate the civic education indexes and consequently render the three indexes and the regression estimates more reliable. (For a similar approach to dealing with potential individual-level biases, see, for example, Page and Shapiro, Reference Page and Shapiro2010; Larcinese et al., Reference Larcinese, Snyder and Testa2013).

In addition to aggregating the three indexes, I standardize these indexes to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 because I am interested in comparing the effect of the three forms of civic education on civic duty and because these school-level indexes now have different distributions. (See Appendix 4 for the indexes’ final distribution.)

Method

This article is aimed at testing whether the link between civic education and civic duty found in Galais (Reference Galais2018) is present for different forms of civic education. I start by examining the relation between civic duty and the three civic education indexes—first individually and then jointly—with the pooled 2016 ICCS data. Because the civic education indexes correspond to school-level aggregates, I run multilevel models, nesting individuals within schools. To account for the country-nested structure of the 2016 ICCS data, I include country fixed effects and use country-clustered standard errors.

Using a multilevel model to examine the correlation between different forms of civic education and civic duty means that controlling for potential (individual-level) confounders is crucial. Notably, it is key that I control for parents’ political interest and occupational status, as those who are politically interested and who come from a wealthy environment might choose a school with a strong civic education program and might consider voting a civic duty more than do their counterparts.Footnote 6 It is also important that I control for respondents’ gender, as male students might attend a school with a strong civic education program and might consider voting a civic duty less than female students do (Hooghe and Stolle, Reference Hooghe and Stolle2004; Carreras, Reference Carreras2018).

Most of what we know about experiences with civic education comes from single case studies (see, for example, Hart et al., Reference Hart, Donnelly, Youniss and Atkins2007; Kahne and Sporte, Reference Kahne and Sporte2008; Flanagan and Stout, Reference Flanagan and Stout2010; Galais, Reference Galais2018). Yet, the education/duty nexus may play out differently in different contexts, not least because the quality of civic education, including the capacity to get students interested in the content of the civic education, varies between schools (Martin, Reference Martin2012; Fahmy, Reference Fahmy2006; Milner, Reference Milner2010). In addition to an analysis of the cross-national pooled ICCS data, I examine the relation between civic education and civic duty with country-specific data, which allows for a more robust assessment of such a relation. More precisely, I perform 23 multilevel regressions, each of which correspond to a country in the 2016 ICCS. As in the main tests with the pooled 2016 ICCS data, these multilevel regressions contain control variables for parents’ political interest and social status, as well as respondents’ gender. Because these regressions focus on a single country each time, there is no need to add country fixed effects or to cluster the standard errors by country, as in the analysis with the pooled data.

Results

To test whether the link between civic education and civic duty is present for different forms of civic education, I run multilevel regressions of civic duty on the three civic education indexes, first individually and then jointly with the pooled dataset, and then run multilevel regressions of civic duty on the same indexes in each country.

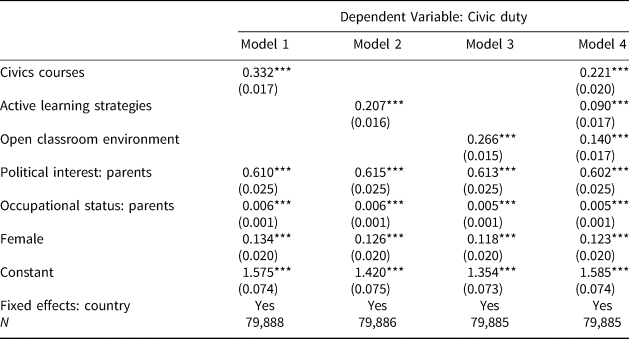

Table 1 lists the results of the pooled analyses. They show that a sense of civic duty is higher among adolescents who are exposed to any of the three forms of civic education than those who are not, and this is so even in the more comprehensive model in which the effect of other forms of civic education is taken into account (see Table 1, columns 1–4). In other words, individuals who are exposed to civics courses, to active learning strategies and to an open classroom environment in adolescence are more prone to consider voting a civic duty than are those with a different school experience.Footnote 7 The results in Table 1 further, and reassuringly, show that the coefficients for the control variables are in line with expectations. Those who are female, whose parents are interested in politics and whose parents are of a high occupational status are more likely to report a belief in the duty to vote than their counterparts.

Table 1. Effect of Different Forms of Civic Education on Sense of Civic Duty to Vote

Note: Entries report log-odds and clustered standard errors (in parentheses). Effects are estimated by means of multilevel logistic regressions, in which students are nested within schools. Civic duty is dichotomous: 0 = voting is not important at all or not very important; 1 = voting is quite important or very important. Higher values of the civic education indexes indicate higher levels of a form of civic education. Data from the 2016 International Civic and Citizenship Education Study.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Given the difficulty of interpreting log-odds, I compute average marginal effects to assess how much civic duty is affected by each civic education mechanism and to compare their effects. They indicate that civics courses are by far the most influential civic duty determinant: an increase of one standard deviation in the learning index is associated with a 2.9 percentage point increase in the likelihood of considering voting a duty, while an increase of one standard deviation in the participation and in the openness indexes is associated with a only a 1.2 and a 1.8 percentage point increase, respectively (see Table 2). In short, these results suggest that civics courses are more correlated with civic duty than the other forms of school socialization.Footnote 8 The effect of civics courses is particularly strong considering that school accounts for 14 per cent of the variance in civic duty in a null model without covariates (not reported).

Table 2. Average Marginal Effect of Different Forms of Civic Education on Sense of Civic Duty to Vote

Note: Entries report the change in the predicted probability of considering voting a civic duty. The corresponding log-odds can be seen in Table 1, column 4. Data from the 2016 International Civic and Citizenship Education Study.

The test of the link between civic education and civic duty by means of the pooled 2016 ICCS data indicates an average stronger relation between civics courses and civic duty than other civic education mechanisms. To gain a better understanding of these relations, I turn to analyses of the country-specific 2016 ICCS data: the key question is now how often each form of civic education affects civic duty. To answer this specific question, I test the relation between civic education and civic duty 23 times, with all civic education indexes and control variables in the model, and then I calculate the average marginal effect 23 times. This analysis looks at all countries in the 2016 ICSS, including Russia. Although Russia's inclusion could be criticized since elections in Russia are not free and fair (Freedom House, 2020), I nevertheless include this country because civic duty entails “the belief that a citizen has a moral obligation to vote in elections,” implying no variation of civic duty according to the political context (Blais and Galais, Reference Blais and Galais2016: 61). Furthermore, previous work has shown that when a sense of duty to vote is internalized, it doesn't change significantly as a function of political context (Feitosa and Galais, Reference Feitosa and Galais2020). With the 2016 ICCS, as well, I find that having free and fair elections does not appear to affect citizens’ sense of duty to vote or the correlation between civic duty and turnout (see Appendixes 6 and 7).

Consistent with the pooled findings, these analyses indicate that civics courses are more strongly associated with civic education than are active learning strategies and open classroom environment. As shown in Figure 1, in 61 per cent of the countries in the sample (that is, 14 out of 23), the effect of the civics courses index is positive and statistically significant. In contrast, the effect of the active learning strategies and the open classroom environment indexes is significant in only 9 and 39 per cent of the countries (that is, 2 and 9 out of 23), respectively. To summarize: a relation between civics courses and civic duty is more frequent cross-nationally than the other civic education mechanisms, implying that results with the pooled ICCS data are robust.

Figure 1. Average Marginal Effect (AME) of Different Forms of Civic Education on Sense of Civic Duty in 23 Countries.

Note: Entries report the change in the predicted probability of considering voting a civic duty. For the sake of space, the corresponding log-odds are not reported. Data from the 2016 International Civic and Citizenship Education Study.

Supplementary Tests

The results so far suggest a role of different forms of civic education on the development of a sense of civic duty to vote, but civics courses are by far the most influential civic duty determinant. In this section, I refine these tests in a number of ways. First, given a reliance on adolescents’ reported experience with civic education, it is possible that these represent an overestimation (or underestimation) of individuals’ actual exposure to civic education. While I have accounted for this possibility by aggregating the civic education indexes at the school level, it is still possible that these indexes are biased, particularly if the number of students per school is low. To address this concern, I perform additional tests in which I exclude all respondents who come from a school with less than the median number of observations (26). As shown in Appendix 8, this leads to a slightly weaker effect of the learning and the participation indexes but a slightly stronger effect of the openness index on civic duty. In addition to resulting in these small changes in the estimates, the additional tests indicate that civics courses remain the most influential civic duty determinant.

Second, the previous tests are based on adolescents who are still in school. As suggested in Greene (Reference Greene2000), it is possible that over the long run, the force of civics courses, in particular, decays. Two Canadian studies—the 2011 and the 2015 Canadian National Youth Surveys (NYS)—offer the opportunity to test the specific effect of civics courses on civic duty with individuals aged 18 years old or older who had already left school. (See Appendix 9 for the total number of respondents and their distribution across the Canadian provinces/territories. See also Appendix 10 for an overview of the variables’ distribution in these supplementary data.)

Table 3 reports the results of these additional tests.Footnote 9 They indicate a positive and significant relation between civics courses and civic duty. That is, Canadians who followed a course on politics in adolescence are still more prone to consider voting a duty in adulthood than those with a different school experience. Computing average marginal effects, as well, indicates that exposure to civics courses is associated with a 4 percentage point increase in the likelihood of considering voting a duty, which is in fact somewhat higher than in the pooled tests. In short, civics courses have an equally strong effect on civic duty among individuals who had left school. The force of civics courses thus seems impervious to the passing of time.Footnote 10

Table 3. Effect of Civic Courses on Sense of Civic Duty to Vote

Note: Entries report log-odds and clustered standard errors (in parentheses). Effects are estimated by means of logistic regressions. Civic duty is dichotomous: 0 = voting is a choice/disagree or strongly disagree that voting is a civic duty; 1 = voting is a duty/agree or strongly agree that voting is a civic duty. Experience with civics courses is also dichotomous: 0 = no; 1 = yes. Data from the 2011 and 2015 Canadian National Youth Survey.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Third, in line with the literature (Neundorf et al., Reference Neundorf, Niemi and Smets2016), the observed results might be sensitive to ceiling effects; that is, the effect of the civic education mechanisms might be weaker among students with a previous high sense of duty to vote. Interacting parents’ political interest and social status with the three civic education indexes indicates, however, no evidence of heterogeneous effects (see Appendix 11). The observed relations between different forms of civic education and civic duty thus seems not conditional on previous civic duty attitudes.

Discussion and Conclusions

While previous work offers indications of the important role of civic education for the development of civic duty (Galais, Reference Galais2018), it remains unclear whether different forms of civic education play a role and are all equally important to developing a sense of duty. In this article, I offer answers to these questions. I find that three key forms of civic education (civics courses, active learning strategies and open classroom environment) have an effect on civic duty but also that civics courses constitute a far more influential civic duty predictor than do the other two forms.Footnote 11

Some caution is warranted when interpreting these results. To begin with, while a study that interviews adolescents from 23 countries on their experience with civic education and their sense of civic duty is unique, the 2016 ICCS covers mostly developed countries that are also in either Europe or Latin America—the exceptions are Hong Kong, South Korea and Russia (to some extent). Still, a focus on these specific countries should not be a problem. First, no discernible trend across regions is observed in the country-specific results, so it seems unlikely that cultural differences play a role when it comes to the relation between civic education and civic duty. Furthermore, a focus on developed countries might mean that the estimated effects of civic education on civic duty are, in fact, conservative; one of the few studies to examine civic education in the context of a developing country reports an effect of civic education on political knowledge in South Africa that is twice as large as in the United States (Finkel and Ernst, Reference Finkel and Ernst2005). The authors of the study, Finkel and Hearst, attribute this difference to the fact that there are fewer means of acquiring political information in South Africa than in the United States. In their words, civic education has the least potential to increase political knowledge “in advanced settings where civics instruction may be redundant to other sources of political information” (Finkel and Ernst, Reference Finkel and Ernst2005: 358). In short, the fact that the 2016 ICCS focuses on mostly developed countries that are also in either Europe or Latin America is unlikely a significant problem.

Some caution is also warranted because civic education is measured by students’ self-reports in this study. While acknowledging that such measures are not perfect, I do not think they invalidate my results. In line with previous research (Page and Shapiro, Reference Page and Shapiro2010; Larcinese et al., Reference Larcinese, Snyder and Testa2013), I aggregate these measures by the schools in the 2016 dataset in order to account for the fact that some students may overestimate or underestimate their experiences with civic education, as well as report experiences with civic education because of an a priori sense of civic duty to vote. The aggregation of students’ measures by schools seems particularly successful, as the number of students who report voting for class representative or school parliament is consistent with directors’ perceptions of voting in schools (see Appendix 13). Furthermore, students’ self-reports are not necessarily biased. Previous work has offered evidence on the validity of these measures in the context of civic education research (see, for example, Finkel and Smith, Reference Finkel and Smith2011).

The influence of the three civic education mechanisms on civic duty is an important finding because it means that schools develop a sense of duty by different and complementary means; that is, by teaching individuals about politics and community affairs, schools can generate a sense of civic duty to vote.Footnote 12 The same outcome is observed when the schools enable a “hands-on” participation in society and in democratic procedures and when they encourage the development and the expression of personal views in an open context.

More importantly, the finding that civics courses—defined as traditional, classroom- based instruction about politics and community affairs—play a bigger role than nontraditional forms of civic education (namely, active learning strategies and open classroom environment) means that Galais (Reference Galais2018), by considering the effect of a single form of civic education (democratic governance), possibly underestimated the role of civic education in instilling a sense of duty to vote. From a policy perspective, this finding also means that the general trend toward active learning strategies to teach youngsters to become good citizens might be worrisome if it means a reduction in teaching civic education through civics courses—a method that has been shown to be the most effective in developing a sense of civic duty among adolescents and ultimately fostering electoral participation. It should also be noted that while this study focused on the relation between civics courses, active learning strategies, open classroom environment and civic duty, active learning strategies (and open classroom environment) may, in fact, be more influential than civics courses when it comes to developing a sense of efficacy—an attitude that plays a particularly important role on participation beyond elections.

To conclude, this article provides evidence that different forms of civic education in schools, especially civics courses, can act upon adolescents, fostering a sense of duty that should persist through adulthood. While my focus is on how well the three forms of civic education (civics courses, active learning strategies and open classroom environment) perform across countries, a number of results in the country-specific analyses are noteworthy; most importantly, it stands out that countries with poorer performance in competences that are also developed at school (such as Mexico) perform better than countries with higher performance (such as Finland) (Schleicher, Reference Schleicher2018). More detailed data are currently unavailable for conducting case studies in order to explain these differences; doing so is also beyond the scope of this article. Nevertheless, these patterns might be explained by the presence, or not, of other sources for the development of duty. Specifically, in line with Finkel and Ernst (Reference Finkel and Ernst2005), civic education might have most potential in places where other socialization agents (for example, the media) are absent. Future work should examine this possibility when the necessary data become available. From a review of the literature, this seems to constitute a good starting point for understanding why civic education is more influential in some countries than in others.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423920000669.