How has the criminal justice system (CJS) responded to racial diversity in the United States? Criminologists and sociologists have led the way in studying the reality of how Blacks are treated relative to Whites by law enforcement and the courts. There is now an extensive literature documenting the far greater likelihood of Blacks being arrested, sentenced and incarcerated compared to Whites, and a fairly contentious literature attempting to sort out the degree to which these racial disparities in outcomes are traceable to racial discrimination in the justice system. Far less attention, however, has been paid to studying perceptions of the fairness of the justice system in the eyes of Blacks and Whites, as well as the political consequences of these perceptions.

We maintain that the huge race gap in these fairness perceptions, which is the focus of this paper, is critically important for a variety of reasons. As we will argue below, most Whites fail to see discrimination in the justice system and consequently believe the system is, for the most part, colour-blind and fair. Because they attribute racial disparities in justice outcomes to the greater criminality of Blacks, they are highly supportive of a slew of punitive policies as the best way to deal with crime. Most African Americans, on the other hand, see discrimination in virtually every nook and cranny of the justice system and do not trust the police or the courts to mete out justice fairly and equitably, especially when people of colour are involved. We argue that in order to understand the polarized reactions of Blacks and Whites to events (such as accusations of police brutality) and policies (such as the death penalty) in the justice system, it is essential to understand the separate perceptual realities that Blacks and Whites inhabit in terms of their beliefs about fairness.

The Importance and Impact of Opinions in the Criminal Justice Domain

An important reason for focusing on citizens' perceptions and opinions in the justice domain is that they matter, perhaps more so than in any other domain since the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s-60s (Miller and Stokes, Reference Miller and Stokes1963). Most obviously, citizens have been empowered to render decisions as a form of direct democracy that is lacking in any other policy area when they serve as jurists, where their beliefs regarding crime and punishment translate directly into determinations of guilt and severity of punishment.

But, more important, is the impact of mass opinion on public policy. In her study of six policy domains, ranging from abortion to welfare to social security, Sharp (Reference Sharp1999) found levels of mass-elite representation to be particularly strong in the crime policy domain, meaning that a heightened sense of punitive beliefs among citizens typically leads policy makers to enact more punitive policies. Further evidence is provided by Canes-Wrone and Shotts (Reference Canes-Wrone and Shotts2004), who analyzed 11 policy areas and, more specifically, the relationship between public opinion on government spending (more, same or less in any given area) and presidents' proposed budgetary authority for a given year. Other than social security, in no other policy domain did the authors find a higher level of presidential responsiveness to mass preferences.

As examples of this public-elite congruence, one need look only at the last landmark anti-crime act in the US, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. Between March 1992 and August 1994, the proportion of Americans regarding crime as the “most important problem” in the Gallup Poll had increased an extraordinary tenfold, from 5 to 52 per cent. In response, the 1994 legislation included, among other components, the “three-strikes” provision, whereby individuals convicted of a third felony (even if nonviolent in nature) must serve mandatory life sentences. Even the judiciary has been shown to base decisions on public opinion. Brace and Boyea (Reference Brace and Boyea2008), for example, found a significant impact of citizen support for capital punishment on the willingness of state judges to uphold the death sentence. Without question, the impact of public attitudes on anti-crime policies is profound.

So what are the results of the government's responsiveness to majority (especially White) opinion over the last three decades? Even a cursory glance at the criminal justice system in the United States reveals two fundamental and distinctive characteristics. First, by almost any standard, the US is the most punitive nation in the world. According to a study released in February 2008 by the Pew Center on the States, “The United States incarcerates more people than any country in the world, including the far more populous nation of China. At the start of 2008, the American penal system held more than 2.3 million adults. China was second, with 1.5 million people behind bars, and Russia was a distant third with 890,000 inmates. America is also the global leader in the rate at which it incarcerates its citizenry, outpacing nations like South Africa and Iran.”Footnote 1 The same study (Pew, 2008: 5) reports that, over the past 30 years, our inmate population has more than tripled, so that, as of this writing, more than one in one hundred Americans is now behind bars.

While these data, taken alone, are staggering, they are germane to our study less because of what they reveal than because of what they obscure, namely, the second fundamental characteristic: the astonishing racial disparities in the prison population. Among White men 18 or over, one in 106 are imprisoned, while the comparable figure for Black men is one in 15. Among Black men between 20 and 34 years of age, fully one in nine are behind bars. According to Mauer's (Reference Mauer2006) projections, almost one-third of Black males born at the beginning of the twenty-first century will spend at least some time incarcerated (compared to six per cent of White males).

With these statistics in mind, we address two questions in this paper. First, we ask how have such racially disproportionate outcomes affected citizens' judgments of the fairness of the CJS; and second, we explore the degree to which such fairness judgments affect citizens' perceptions of agents of the CJS (such as police officers) and positions on anti-crime policies (such as capital punishment). Given the crucial role played by public opinion as a determinant of public policy in this domain, these are clearly important questions.

Perceptions of Justice in America

Racial disproportionalities in the prison population represent merely the tip of the iceberg. There is an enormous literature documenting a race-of-victim effect: crimes against Whites result in significantly faster police response times (Bachman, Reference Bachman1996), higher probabilities of arrest (Williams and Farrell, Reference Williams and Farrell1990) and prosecution (Myers and Hagan, Reference Myers and Hagan1979) and more “vigilant” investigative strategies (Bynum et al., Reference Bynum, Cordner and Greene1982). And, most dramatically, it is quite well established that assailants who murder Whites are significantly more likely to be executed than those who murder Blacks (Gross and Mauro, Reference Gross and Mauro1989; Keil and Vito, Reference Keil and Vito1995). Additionally, there is also voluminous documentation of a race-of-suspect effect: police are more likely to use force and to arrest African American suspects, as well as to engage in racial profiling of motorists—the so-called “driving while Black” phenomenon (Harris Reference Harris1999).

Racial disparities are not limited to differential treatment of citizens; they can also infiltrate the laws themselves. The best known example is the notorious 100-to-1 provision of the Federal Crack Cocaine Law of 1986 (21 U.S.C. 841), which mandates the same five-year prison sentence for 100 grams of powder cocaine (used primarily by Whites) as for one gram of crack cocaine (used primarily by African Americans), despite the gram-for-gram pharmacological equivalence of the two drugs (Stuntz, Reference Stuntz1998).

There is considerable debate regarding the degree to which such racial disparities represent true discrimination (as argued, for example,, by Walker et al., Reference Walker, Spohn and DeLone2004) as opposed to a more even-handed treatment of African American offenders who are punished more severely because of “legally relevant considerations” (such as more prior convictions, more frequent use of firearms) (see Lauritsen and Sampson, Reference Lauritsen, Sampson and Tonry1998).Footnote 2 Given the fact that even legal scholars disagree in their interpretation of the available evidence, we can safely assume that average citizens are forced to formulate their judgments about the fairness of the justice system in an environment of incomplete and highly uncertain information. As a result, they should be quite likely to fill in many of the missing pieces based on their own personal experiences and cultural stereotypes of both the other race and of the agents of the justice system (that is, police officers and court personnel). There is abundant evidence, for example, that African Americans are doubly frustrated by the CJS, both because they are the most dependent on it for help, given their higher rates of victimization, and because of a widespread distrust of those whose protection they need (Meares, Reference Meares1997). There is also considerable evidence (see Hurwitz and Peffley, Reference Hurwitz and Peffley1997) that many Whites see Blacks as characteristically violent and therefore deserving of punitive treatment from an equitable system. Thus, even though Blacks and Whites might see the same racial disparities in outcomes, such as prison populations (PEW, 2008) or vehicular stops (Harris, Reference Harris1999), we expect the races to differ markedly in interpretations of such outcomes. Specifically, we expect Blacks to be more likely to believe that a discriminatory CJS has led to racially disproportionate outcomes, and Whites to believe that the system is essentially “colour-blind,” merely responding to a race they see as characteristically violent with an appropriate level of punitiveness.

In examining Blacks' and Whites' fairness judgments, we must take into consideration the target of (un)fairness. Others (see Tyler and Folger, Reference Tyler and Folger1980) have focused on fairness perceptions at a personal level (exploring the degree to which individuals feel the justice system has treated them fairly). Following perceived fairness theory (Lind et al., Reference Lind, Tyler and Huo1997; van den Bos et al. Reference Van den Bos, Lind, Vermunt and Wilke1997, Reference Van den Bos, Lind, Wilke and Cropanzano2001), we argue that it is essential to broaden our thinking of fairness to examine more global beliefs about the wider criminal justice system, since it is such global assessments that, once formed, serve to guide individuals' responses to events (such as police brutality) and policies (such as capital punishment) in the justice domain. Such deductive reasoning (from abstract beliefs to specific attitudes) is also consistent with the massive information processing literature (see Fiske and Taylor, Reference Fiske and Taylor2007).

An emerging psychology of legitimacy literatureFootnote 3 argues that global fairness appraisals can occur at: 1) the system level, where individuals assess the fairness of the system that produces outcomes, whether economic, social or criminological in nature; and 2) the group level, where individuals assess whether the allocation of outcomes to one group is fair or just (Major and Schmader, Reference Major, Schmader, Jost and Major2001: 180).

We will have more to say about the measurement of these targets of fairness assessments below. For the moment, we simply note that measures of system fairness must be devoid of the kinds of references to specific groups (such as Blacks) or outcomes (such as allegations of police discrimination) and must ask about quite general assessments of the global system. Group fairness, on the other hand, can be conceptualized (and measured) in different ways. We find many parallels in the economic domain, where individuals routinely make a variety of assessments about whether their group is receiving a fair distribution of outcomes vis à vis other groups. A good deal of research cutting across several disciplines finds that people possess an assortment of naïve theories or explanations of why groups receive unequal economic outcomes, that is, why the poor are poor, why Blacks are worse off than Whites or why males are generally paid more than females. For the most part, such beliefs take the form of causal attributions, locating the locus of cause of good or poor outcomes to either internal forces (such as individual effort, ability and similar characteristics) or external ones (such as an unfair system, bad luck).

An analogous set of causal attributions should be every bit as important in the justice domain, as individuals form naïve explanations of why Blacks receive far more punitive treatment at the hands of the justice system than Whites. Just as economic conservatives are far more likely than liberals to oppose government assistance for the poor if they believe poverty to be a function of dispositional factors, such as laziness, versus environmental factors, such as poor schooling or widespread unemployment (see, for example, Applebaum, Reference Applebaum2001; Gilens, Reference Gilens1999; Iyengar, Reference Iyengar1989), social conservatives should be more inclined to favour a more punitive approach toward criminal behaviour when it is attributed to dispositional rather than environmental or mitigating factors (see Cochran et al., Reference Cochran, Boots and Heide2003).

Not only do we expect Blacks and Whites to differ considerably in their fairness judgments at the system and group levels, but we also expect system and group fairness judgments to serve different functions. As respondents interpret events in the justice system—particularly an event that requires an evaluation of an actor (such as a police officer)—they should be strongly influenced by system fairness judgments. It is, after all, such global evaluations that motivate individuals to formulate interpretations that are either cynical toward, or accepting of, the role of the authority figure. On the other hand, we believe that anti-crime policy attitudes should be influenced by group fairness judgments. There is considerable evidence that citizens are more punitive when they attribute criminal behaviour to dispositional considerations rather than to environmental factors such as a discriminatory justice system (see Grasmick et al., Reference Grasmick, Tittle, Bursik and Arneklev1993; Young, Reference Young1991).

Data and Measures

To examine citizens' perceptions of the fairness of the US CJS, we administered the National Race and Crime Survey (NRCS), a nationwide telephone survey of approximately 600 (non-Hispanic)Footnote 4 Whites and 600 African Americans in the 48 contiguous states.Footnote 5 White respondents were selected through a variant of random digit dialing procedures, along with a stratified oversample of Black respondents.Footnote 6 Professional interviewers at the Survey Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh Center for Social and Urban Research spoke with respondents for an average of 30 minutes between October 19, 2000, and March 1, 2001.Footnote 7 While we will have more to say about survey items below, we note that respondents were asked not only to evaluate system fairness, but also to respond to questions regarding a variety of anti-crime policies and to a series of vignettes involving confrontations between police officers and civilians.

System-level beliefs. As noted, views of system fairness should be pitched at a general level. Our index of perceived system fairness, therefore, consists of two Likert items: “The justice system in this country treats people fairly and equally”; and “The courts can usually be trusted to give everyone a fair trial” (r = .59).

Group-level beliefs. Judgments about the fairness of the justice system to a given group (that is, African Americans) largely hinge on explanations of outcomes: whether an uneven outcome can be attributed to bias in the system or, instead, to failings of the members of the group. For this reason, we rely heavily in this paper on a measure of attributions of black treatment, designed to assess respondent explanations of racial disproportionalities in arrest and incarceration rates and, more specifically, to assess the degree to which respondents attribute these outcomes more to internal (such as a violent temperament) or to external (such as a biased justice system) explanations. Specifically, we ask them:

Statistics show that African Americans are more often arrested and sent to prison than are Whites. The people we talk to have different ideas about why this occurs. I'm going to read you several reasons, two at a time, and ask you to choose which is the more important reason why, in your view, Blacks are more often arrested and sent to prison than Whites.

First, is it because the police and justice system are biased against Blacks, or because Blacks are just more likely to commit crimes?

Next, is it because the police and justice system are biased against Blacks, or because many younger Blacks don't respect authority?

The responses to these items are summed to create an Attributions of Black Treatment scale (r = .42 for Whites, .35 for Blacks) in which, at one extreme, respondents consistently selecting external explanations of African American crime (police bias) are coded zero, while, at the other extreme, respondents who consistently selected dispositional explanations (more likely to commit crime, don't respect authority) are coded four.

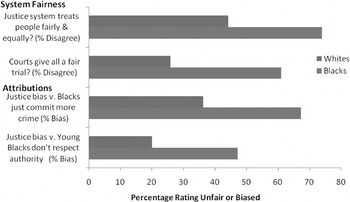

Figure 1 displays the huge gulf between Whites' and Blacks' beliefs about system fairness and attributions of black treatment. Interracial differences are quite staggering, as the race gap averages approximately 30 percentage points. We gain even more perspective on racial polarization by comparing responses, not to individual items, but to the full additive scales, System Fairness and Attributions of Black Treatment. For example, on the System Fairness scale, which ranges from 0 [very unfair] to 6 [very fair], the average Black respondent falls close to the “very unfair” end of the scale (1.2), while the average White falls much closer to the opposite (“very fair”) end of the System Fairness scale (3.4). The modal response of Blacks is 0, while that of Whites is 4 (p < .001).

Figure 1 Racial Differences in Beliefs about System Fairness and Attributions of Black Treatment

Source: NRCS data.

Note: Differences across race of respondent are statistically significant (≤.01), based on ANOVA.

Responses to the Attributions scale are just as polarized, if not more so. On a scale ranging from 0 (attributions to racial bias) to 4 (Blacks are entirely to blame), the average African American again scores toward one end of the scale (system blame, 1.47) and the average White falls closer to the opposite end (2.5, blame Blacks). And, on this measure, the modal responses of Blacks and Whites are the extreme end-points of the scale: 0 among Blacks and 4 among Whites (p < .001). It is, therefore, no exaggeration to conclude the races are polarized in their assessments of fundamental questions about the fairness of the justice system at both the system and group levels. It is impossible to avoid the conclusion that Blacks and Whites inhabit two separate perceptual domains.

The Consequences of Separate Perceptions

The findings to this point would mean little in the absence of evidence that such inter-racial differences are consequential. But, as will be shown below, the cynicism expressed by many African Americans and the assumptions of fairness derived by most Whites, prove to be profoundly important. To be sure, such beliefs influence the ways that individuals of both races interpret the behaviours of agents of the criminal justice system (in this case, police officers), as well as policy attitudes in the justice domain.

The Impact of Fairness Judgments on Perceptions of Police Conduct

We designed the police brutality experiment, in which we present respondents with a vignette involving a police officer accused of brutalizing a civilian who is either White or African American, for two purposes. First, it is designed to assess the impact of general (systemic) fairness judgments on perceptions of police conduct: do those (primarily Black) respondents who believe the system to be inherently unfair interpret police conduct more cynically than those (primarily White) respondents who believe the system to be inherently fair? And second, it is designed to examine whether the race of the civilian plays a role in respondents' interpretations of allegations of police brutality.

Specifically, in this experiment, we ask respondents about “a recent incident in Chicago in which a police officer was accused of brutally beating a [White/Black] motorist who had been stopped for questioning. The police department promised to investigate the incident. How likely do you think it is that the police department will conduct a fair and thorough investigation of the policeman's behaviour?” Respondents were randomly assigned to either the Black or the White motorist condition, meaning that any differential responses across treatment groups can only be attributed to the race of the motorist. The dependent variable is a four-point scale ranging from “very likely” (1 on the scale) to “very unlikely” (4 on the scale) that the police department will conduct a fair investigation. The results of an ordered probit model regressing the dependent variable (Fair investigation unlikely?) on System Fairness as well as the race of the motorist, anti-Black stereotypes, and interactions between race of motorist and the other two predictor variables are presented in Table 1. What merits our most careful attention in the table is the statistically significant impact of System Fairness on judgments of whether the police will investigate the brutality incident for both Black and White respondents, as well as the significant interaction between fairness and race of the motorist only for Black respondents. Because probit coefficients are difficult to interpret, we present a graph (Figure 2) of the predicted probability of a fair investigation (very plus somewhat likely) holding other variables at their means.Footnote 8 The judgments for Black respondents are depicted by solid lines, with dotted lines used for Whites.

Table 1 Predicting Responses to the Police Brutality Experiment

Source: NRCS data.

Note: Entries are ordered probit regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. Higher values on the above variables indicate: fair investigation unlikely, White motorist/victim of police brutality (1), believing the justice system is fair, and more negative stereotypes of Blacks than Whites. System Fairness ranges from −3 (very unfair) to +3 (very fair), with 0 being the midpoint of the scale. The natural midpoint of the Anti-Black Stereotype scale is approximately 0 for both Blacks and Whites.

* p < .05,

** p < .01

Figure 2 Predicted Probability of Judging Fair Investigation Likely across Fairness, Race of Motorist, and Race of Respondent

One is struck, first, by the large impact of the race of the motorist on African American respondents (solid lines) who think the justice system is unfair (the left hand side of the fairness scale). Blacks who think the system is very unfair (at −3 of the fairness scale) are more than twice as likely to think the police investigation will be fair when the motorist is White (55 per cent) than when he is Black (24 per cent). Clearly, Blacks who are cynical about the justice system—and most of them are quite cynical—are extremely pessimistic about a Black victim of brutality receiving justice at the hands of the police compared to a White victim. On the other hand, the relatively small number of Blacks who believe the system is very fair (on the right side of the scale) think a fair investigation into the officer's conduct is about as likely for a Black motorist (60 per cent) as for a White motorist (65 per cent).

The figure also neatly documents that general fairness beliefs do not play the same role for Blacks as they do for Whites. Perhaps the greatest single difference in the way the races respond to the scenario is that, among African American respondents, general fairness beliefs are much more important in shaping their evaluation of the incident when the brutality victim is Black than when he is White. Among White respondents, however, the probability estimates are nearly identical, regardless of the race of the victim. Whites (who tend to assume that the system is colour-blind) apply their fairness beliefs as if the race of the victim has no bearing on whether the police would conduct a fair investigation.

These results suggest that when Blacks are asked about the general fairness of the justice system, even though no mention is made of race in either question, Blacks are much more likely to interpret such questions as an evaluation of whether the system is fair and equal to African Americans. Consequently, such beliefs are more likely to influence evaluations of the police when Black respondents are asked about African American targets. White respondents, however, naively process the fairness items in a racial vacuum, as if it is possible to evaluate the fairness of the justice system without reference to race. Thus, not only do Blacks and Whites come to the scenarios with very different prior beliefs, but their responses to the scenarios diverge, in part, because the actual meaning of fairness beliefs varies across the races.

The Impact of Fairness Judgments on Anti-Crime Policy Attitudes

One of the ways we have measured beliefs about the fairness of the justice system is by assessing the degree to which respondents believe the system treats equitably various groups—in this case African Americans. Specifically, we have relied on our Attributions of Black Treatment measure for this purpose. At one end of the spectrum are those (primarily Black) individuals who explain the fact that Blacks are more often arrested and incarcerated using structural arguments, that is that the system is biased against African Americans. The other end is anchored by (primarily White) respondents who employ dispositional explanations, such as a belief that Blacks are just more likely to commit crimes or that they do not respect authority.

The importance of this indicator is not merely in documenting a profound inter-racial difference in beliefs about the racial fairness of the justice system. Rather, it is that such attributional explanations of Black treatment are fundamentally important in guiding individuals' anti-crime policy views, depending on how the issue is framed.

We embedded a death penalty experiment in the NRCS, mainly designed to examine the susceptibility of respondents to various anti-death penalty arguments. Surveys have consistently found strong support for capital punishment in the US (see Ellsworth and Gross, Reference Ellsworth and Gross1994), but also that such support is conditional and likely to fluctuate when respondents are informed that the penalty is not a deterrent to murder, when informed that innocent people are sometimes executed or when informed that execution is more expensive than a life sentence. Additionally, individuals are less supportive when the murderer is under 18 or mentally retarded (Longmire, Reference Longmire, Flanagan and Longmire1996: 103). Clearly, the large majorities of respondents who express support for capital punishment should be at least somewhat susceptible to counterarguments.

In our death penalty experiment, we compare the efficacy of two very different arguments against capital punishment, one that contains a racial frame and one that does not, looking particularly at how the impact of the two messages differs across the race of the audience. In the baseline condition (to which one-third of our respondents have been randomly assigned), individuals simply respond to the question: “Here is a question about the death penalty. Do you strongly oppose, somewhat oppose, somewhat favour, or strongly favour the death penalty for persons convicted of murder”? In the racial argument condition, individuals are asked the same question, only preceded by the statement “Here is a question about the death penalty. Some people say that the death penalty is unfair because most of the people who are executed are African Americans.”; and in a non-racial argument condition, the baseline question is preceded by “Some people say that the death penalty is unfair because too many innocent people are being executed.”

Table 2 displays the results across the three experimental conditions, baseline (column 1) versus racial argument (column 2) versus innocent argument (column 3), separately for White and African American respondents. Most obviously, the data indicate that Whites are significantly more supportive of the death penalty (in all three conditions) than are African Americans.

Table 2 Percentage Support for the Death Penalty, by Race and Experimental Condition

Source: NRCS data.

Note: The experiment also randomly manipulated the source of the argument as either “some people” or “FBI statistics show that,” which had no discernible influence on support for the death penalty.

Differences across baseline and argument conditions, and across respondent race, are significant at p<.01.

But it is the magnitude of this difference, and what happens to this magnitude across experimental treatments, that is of greatest interest. African Americans respond to the anti-death penalty arguments in the fashion that one would predict based on the direction of the message, that is, they become more opposed. While half of the Black respondents support capital punishment in the baseline, support drops to approximately one-third of respondents in the two treatment conditions. Somewhat surprisingly, the innocent argument has a modestly greater impact on them (causing a decrease of 16 per cent versus 12.1 per cent in response to the racial argument). Quite possibly, African Americans do not need to be reminded of the racial discrimination inherent in the death sentence and, consequently, the message provides less in the way of new information.

It is the response of White respondents, however, that is particularly revealing. While the innocence argument makes virtually no difference, Whites in the racial condition, upon hearing of the discriminatory properties of the death penalty, actually become more, rather than less, supportive, to the point where more than three out of four individuals favour capital punishment in this treatment group.

Our primary interest, however, is in the degree to which support for the death penalty and, more specifically, susceptibility to counterarguments, is affected by respondents' views of the causes of Black arrest and incarceration rates (that is, Black Treatment). Are those who hold structural explanations (the system is biased against Blacks) less punitive in their policy attitudes, while those who hold dispositional explanations (Blacks are more likely to commit crime or they don't respect authority) more punitive? To investigate this question, we estimated an ordered probit model predicting support for the death penalty from Black Treatment and a variety of control variablesFootnote 9 for Black and White respondents for each of the three argument conditions. Table 3 reports the coefficient for Black Treatment for the six estimated equations. Among African American respondents, the Black Treatment variable has a strong and significant impact on support for capital punishment in all three treatment groups.

Table 3 Predicting Support for the Death Penalty across Race and Experimental Conditions

Source: NRCS data.

* p < .10,

** p < .05,

*** p< .01

a Coefficient is statistically different across baseline and racial argument conditions (≤.05). Statistical significance across the race of the respondent is based on models estimated for each condition pooled across race that included a race dummy and interactions between race and each of the predictors.

Note: Entries are ordered probit regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. Higher values indicate greater support for death penalty and more dispositional attributions of black treatment. Equations also included several control variables: general attributions of crime, anti-Black stereotypes, fear of crime, punitiveness, partisanship, ideology, education, gender, income and age.

Among White respondents, however, the impact is more restricted. In the baseline and innocent treatment groups, the attributions of Black treatment variable is neither strong nor statistically significant. However, Whites in the racial treatment group are substantially more punitive when they hold dispositional, rather than structural, views of Black treatment. What accounts for the “boomerang” or “backlash” effect in response to the racial argument among Whites observed in Table 2? In Figure 3 we present the predicted probabilities for Whites' support for the death penalty across the Black Treatment scale when they are presented with the racial argument. We see in Figure 3 that strong support for the death penalty increases from 28 per cent to 64 per cent as one moves from more structural (that is, environmental) to more dispositional (that is, personal) attributions. Many Whites begin with the belief that the reason Blacks are punished is because they deserve it, not because the system is racially biased against them. So when these Whites are confronted with an argument against the death penalty that is based on race, they reject it with such force they end up expressing more support for the death penalty than when no argument is presented at all.

Figure 3 Whites' Probability of Death Penalty Support for Racial Argument across Attributions of Black Treatment

Source: NRCS data.

Note: Predicted probabilities based on the regressions in Table 3.

Conclusions and Discussion

In this analysis, we have distinguished between two different levels at which individuals appraise the fairness of the criminal justice system: at the systemic level, and at the group level. In the first instance, they take a more global perspective, formulating an overall assessment of the performance of the justice system. And in the second, they rely on evidence regarding the evenhandedness with which the system has treated various groups (particularly minority groups) in society. And we have provided compelling evidence that, regardless of the level at which fairness is evaluated, African Americans are consistently more cynical relative to Whites.

Whites see a justice system that is essentially colour-blind. They tend to believe that African Americans are dispositionally oriented to crime and, consequently, tend to have no problem with the differential apprehension, prosecution and incarceration rates in the penal system. After all, individuals should be punished according to the degree of culpability. And if one believes that a class of citizens is habitually in violation of the law, then the only logical conclusion is that the system works properly (and fairly) to the degree that it metes out harsher punishment to such citizens.

African Americans, however, live in a separate perceptual world. They are far more likely to experience what they perceive to be unfair treatment from the law—a fact that translates into the belief that discrimination is pervasive in the community. Perhaps most importantly, they tend to regard race-differential outcomes as the product of bias in the system, not of anything characteristically unlawful about Black individuals. In short, they see a system that is simply incapable of meting out justice evenly and fairly. By any benchmark in the public opinion literature, whether studies of the gender gap, or even Black-White differences in the economic domain, this chasm is enormous.

The Consequences of Racial Division

Most importantly, these different conceptions of justice in the United States are, to say the least, consequential, for they provide lenses through which both Blacks and Whites process information about the criminal justice system in this country. We have shown, for example, that those (mainly African Americans) who are most cynical about the fairness of the justice system are also far more likely to be skeptical that the police can or will conduct a fair investigation in an alleged brutality case—at least when the civilian is also African American. But Whites make no distinction based on the colour of the civilian, regardless of whether he is White or African American. Rather, they believe that: a) the investigation will be fair, and b) it will be comparably fair for civilians of both races.

Not surprisingly, perceptions of fairness are also closely linked to policy attitudes, at least in the case of the death penalty. In our Capital Punishment Experiment respondents were randomly assigned to one of three groups. All three groups were asked about the death penalty, but those in the “race” condition were informed that it is racially discriminatory, and those in the “innocent” condition were informed that innocent people are sometimes executed.

African Americans, we found, do not need to be reminded of the racially discriminatory nature of the justice system, as evidenced by the fact that those who attribute the higher arrest and incarceration rates for Blacks to bias in the justice system are substantially more oppositional to capital punishment than are those who attribute such outcomes to the unlawful and disrespectful characteristics of African Americans. And this is true regardless of the condition to which Black respondents are assigned. Whites, on the other hand, evaluate capital punishment more selectively, basing their judgments on beliefs about the bias of the justice system only when informed that the penalty is racially discriminatory.

Given the greater distrust of African Americans of justice system, and given the tendency of Blacks to link their policy attitudes to this generalized distrust (at least on the death penalty), it would be surprising if we did not find such large interracial differences with respect to policy attitudes. What did surprise us, however, is the ease with which attitudes on seemingly race-neutral policies become racialized. In the Capital Punishment Experiment, what began as a 15 per cent difference in approval for the death penalty between Blacks and Whites almost tripled (to 40 per cent) once respondents were informed that the death penalty, according to “some people,” is used in a racially discriminatory fashion. African Americans, predictably, became even more oppositional to the penalty, while, shockingly, a nontrivial number of Whites became more supportive once informed that the punishment is administered disproportionately to Blacks.

Does this mean that Whites harbour racial prejudice and base their evaluations of justice on a bigoted belief system? We do not have the leverage to arrive at such conclusions. We are, however, in agreement with Bobo and colleagues (Reference Bobo, Kluegel, Smith, Tuch and Martin1997), who have argued that “Jim Crow racism” has been largely replaced by what they term “laissez faire racism.” Whites no longer believe that Blacks are biologically inferior, just as they no longer support strict segregation and open discrimination. In the contemporary environment, however, Blacks are still “stereotyped and blamed as the architects of their own disadvantaged status.” Although Bobo and colleagues apply the concept of laissez faire racism primarily to the economic system, it is also eminently applicable to the justice system. Because most Whites believe the justice system is fair and equitable, no remedial policies are necessary to correct racial disparities or restore an imbalance in racial justice. And believing that the justice system provides equal treatment to all, that it punishes only those individuals who deserve to be punished and that the punishment fits the crime, allows Whites to turn a blind eye toward the many forms of racial injustice that are so pervasive in the Black community. Indeed, it allows many Whites to be morally offended by staggering rates of Black incarceration because they are seen as further evidence of Black proclivities toward crime. And the mere suggestion that the system is racially unfair creates an indignant response among many Whites, who take it as an article of faith that the system is largely colour-blind.

The Public-Elite Link

At the beginning of this paper, we posed two related questions: how do the racially disproportionate outcomes that characterize the US CJS affect citizens' judgments of fairness?; and b) how do such fairness judgments affect citizen attitudes toward agents of the system and toward anti-crime policies? These are important questions, for there is a close reciprocal relationship between public preferences and public policy in the criminal justice domain: just as policy makers pay close attention to (especially majority) public opinion, public opinion is strongly shaped by the results of the policies that have been put into place.

Given the great importance of public preferences, it is reasonable to question the character and the quality of mass attitudes. But we have found, consistently, that there is no such thing as a unified set of beliefs in this domain. To the contrary, there is a high level of racial polarization, with an African American population that is largely cynical and suspicious of real justice and a White population that is largely convinced that the CJS is fair.

What is most troubling is the nature of majority opinion—presumably the opinion that matters most to political elites. At best, Whites see the system as colour-blind and as capable of dispensing justice that is evenhanded and fair. While we do not go so far as to label Whites' beliefs as based in bigotry, we do maintain that many Whites fail to recognize what should be so obvious, that the massive racial disproportionalities (in apprehensions, arrests, convictions, an incarcerations) are at least somewhat indicative of a discriminatory justice system. And at worst, as demonstrated in our death penalty experiment, blatant bigotry seems to underlie the support for capital punishment for a nontrivial number of Whites. There is ample reason to question a criminal justice policy that is fuelled by such beliefs.

What of the second part of the equation, that public opinion is highly responsive to public policies? Quite clearly, the draconian “get-tough” policies enacted by federal and state governments during the 1980s and 1990s have served to increase prison populations to an extraordinary degree and, even more, to increase the racial disproportionalities of this population. Do we have reason to suspect that policies will change, now that there is a new leadership in Washington as a result of the 2008 elections? If so, would mass beliefs begin to shift?

Even before the 2008 elections, which ushered in both the nation's first African American president and two Democratically controlled congressional chambers, one could find considerable evidence that policy makers at all levels had begun to take a fresh look at the draconian policies of previous eras, as then-Senator Biden was the lead sponsor of a bill (with the co-sponsorship of then-Senator Obama) in the 110th Congress to eliminate the 100-to-1 sentencing disparity for using comparable quantities of powder and crack cocaine, respectively, a disparity built into the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. Since the election, serious reform proposals are receiving attention and endorsement. The Obama Administration, in fact, has taken the most forceful position possible in its declaration that the sentencing discrepancy should be eliminated entirely. As expressed by Attorney General Eric Holder, in remarks to the Washington DC Court of Appeals,Footnote 10 “It is the view of this Administration that the 100-to-1 crack-powder sentencing ratio is simply wrong. It is plainly unjust to hand down wildly disparate prison sentences for materially similar crimes. It is unjust to have a sentencing disparity that disproportionately and illogically affects some racial groups.” Additionally, support for reform is increasingly bipartisan in nature, with even conservative Republicans agreeing on the need for sentencing equalization (Mauer, Reference Mauer2009).

But the federal government is poised to address more than just drug sentencing guidelines. During the same week in June 2009, two Congressional committees held hearings on two important criminal justice bills. The House heard witnesses testify in support of the Juvenile Justice and Accountability Improvement Act of 2009, which is designed to eliminate sentences of juvenile life without parole.Footnote 11 And of even greater potential importance, only two days later a Senate subcommittee held hearings on The National Criminal Justice Commission Act of 2009, which would establish a blue-ribbon commission to conduct an 18-month comprehensive review of the nation's criminal justice system, culminating in a report offering concrete recommendations for reform.Footnote 12

There is no guarantee, of course, that the justice system's approach to crime in the United States will undergo the types of changes that now look quite feasible. It will always be the case that elected officials will cower when they believe they may be labelled “soft on crime.” Nonetheless, criminal justice reform is more probable now than at any time in the last 30 years. We do not know, of course, how this will affect public judgments of the CJS. We do not know if African Americans will become more trusting or if the more racially balanced prison populations will begin to cut into the perception of many Whites that African Americans should be treated in a more punitive fashion because they are, in fact, more deserving of such treatment. Whatever the outcome, the response of the US justice system to racial minorities is poised for reform.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation (Grant # 9906346). The authors are grateful for the assistance of the Survey Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh, as well as for the helpful comments from Allison Harell, Dietlind Stolle and the two anonymous CJPS reviewers.

APPENDIX

Selected NRCS Survey Items

Anti-Black Stereotypes. [Ratings of “most whites” are subtracted from ratings of “most blacks”]: Please tell me using a number from 1 to 7 how well you think the word or phrase describes MOST [BLACKS/WHITES]. If you think it's a VERY POOR description of MOST [BLACKS/WHITES], give it a 1. If you feel the word is a VERY ACCURATE description of MOST [BLACKS/WHITES], give it a 7. And, of course, you may use any number in between. First, what about lazy? Prone to violence? Prefer to live on welfare? Hostile? Dishonest?

General Attributions of Crime. Similar to our measure of Attributions of Black Treatment, respondents were asked to choose between pairs of dispositional and structural causes, but instead of asking about Blacks, we asked whether generic causes of crime.

Choose the one you feel is the MORE IMPORTANT cause of crime.

First, do you feel crime is caused more by poverty and lack of opportunity, OR by people being too lazy to work for an honest living?

Poverty and lack of opportunity, OR because many younger people don't respect authority?

Punitiveness. An additive index of agreement with the following Likert items:

Parents need to stop using physical punishment as a way of getting their children to behave properly.

One good way to teach certain people right from wrong is to give them a good stiff punishment when they get out of line.

Fear of Crime. How worried are you about you or a family member of your family being a victim of a serious crime: very worried, somewhat worried, only a little worried, or not worried?