1. Ideophones: the fallacy of rarity

Interest in sound symbolism is not new in linguistics.Footnote 1 Indeed, since Plato's Cratylus there have been multiple attempts to explain how and why some sounds are related to some meanings (see Allot Reference Allott and Figge1995, Nuckolls Reference Nuckolls1999, Magnus Reference Magnus2001, for a review). Despite this interest, the role of these sound-meaning-motivated words in general linguistic theory has been until recently quite marginal. There might be different converging factors that explain this situation. I will name just three that are relevant to the topic of this paper: (i) statements made by influential linguists such as de Saussure who argued that “onomatopoeic formations are never organic elements of a linguistic system. Besides, their number is much smaller than is generally supposed” (de Saussure Reference de Saussure, Bally, Sechehaye and Riedlinger1959: 69), (ii) the tendency to believe that what happens in European languages such as English or French is applicable to all the languages of the world, and (iii) the general practice of trying to fit the linguistic data of a non-European language into the traditional Latinate grammatical categories and characteristics (e.g., parts of speech, function, etc.).

As a result, these words have been usually identified with very specific parts of the lexicon such as animal sounds (cock-a-doodle-doo), noises (ding-dong), and nursery vocabulary (clippity clop, pitter-patter, wibble wobble). In short, they have been regarded as curiosities or “marginal exceptions” (Hockett Reference Hockett1958: 677) and their frequency “vanishingly small” (Newmeyer Reference Newmeyer1993: 758).

However, this general picture is quite inaccurate. A closer look at the linguistic resources of various languages, including English and French (see, for instance, Nodier Reference Nodier1808 or Smithers Reference Smithers1954), shows that there are certain linguistic units that clearly stand out from the rest of a language's vocabulary. They are intuitively considered ‘expressive’ by native speakers and are linguistically ‘foregrounded’ in several formal ways. This type of linguistic unit receives different names (mimetics, expressives, echo words…) but I will refer to them with the cover term ideophone, first introduced by the Africanist Doke (Reference Doke1935), and defined by Dingemanse (Reference Dingemanse2011: 25) as “marked words that depict sensory imagery.”

In recent years, there is a growing body of research on ideophones, not only from a linguistic perspective (see, for instance, the now-classic Hinton et al. Reference Hinton, Nichols and Ohala1994, and Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz Reference Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001, as well as the recently published special issue of Pragmatics and Society: Lahti, Barrett, and Webster Reference Webster2014) but also from less-related linguistic fields such as branding and marketing (Klink Reference Klink2000, Reference Klink2003; Yorkston and Menon Reference Yorkston and Menon2004; Shrump et al. Reference Shrump, Lowrey, Luna, Lerman and Liu2012; Velasco et al. Reference Velasco, Salgado-Montejo, Marmolejo-Ramos and Spence2014). Although ideophones have traditionally been considered central parts of the linguistic structure of some languages, mostly African, Asian (Japanese) and American languages (see, for instance, Samarin Reference Samarin1965, Nuckolls Reference Nuckolls1996, Hamano Reference Hamano1998, Childs Reference Childs2003), the truth is that they are by no means rare in European languages, as I shall demonstrate with the analysis of Basque ideophones to be presented here (see also Riera-Eures and Sanjaume Reference Riera-Eures and Sanjaume2010 for Catalan, and Mikone Reference Mikone, Erhard Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001 for Balto-Finnic languages). The structure of the article is as follows. Section 2 describes some of the main linguistic characteristics of Basque ideophones. Section 3 situates Basque ideophones in a typological context. Finally, Section 4 summarises some of the results and points to future lines of research.

2. Basque ideophones

Before beginning the linguistic description of Basque ideophones, it is necessary to offer a brief account of the state of these units in Basque linguistics, where the term traditionally adopted to refer to these elements is onomatopoeia. The existence of onomatopoeia in Basque has long been acknowledged. Schuchardt (Reference Schuchardt1925: 18) states that das Baskische ist sehr reich an deutlichen Schallworten [Basque is very rich in clearly onomatopoeic words]. However, the level of interest in the study of these words has not always been steady in Basque linguistics. Three different periods can be distinguished.

The first period, which I will call traditional Basque studies, considers onomatopoeia as one of the main characteristics of the Basque language, a trait of Basque primitivism, where primitive means native and old. These studies, dating back to the first half of the 20th century, were usually descriptive and based their linguistic insights on real oral data collected village by village, speaker by speaker (cf. Azkue Reference Azkue1905–1906). In this group, the work of Zamarripa (Reference Zamarripa1914), Azkue (Reference Azkue1923–25), de Alzo (Reference de Alzo1961), and de Lecuona (Reference de Lecuona1964) may be mentioned.Footnote 2 All of these studies include sections and chapters where they either offer a list of some of the most common onomatopoeias (Azkue, Zamarripa) or a brief description of their linguistic characteristics and usage (de Alzo, de Lecuona).

A second period, which I will call modern Basque linguistics, covers most of the work carried out in Basque linguistics in the latter part of the 20th century and the very beginning of the 21st century. Here, grammatical descriptions of the language such as that by the Euskaltzaindia [Royal Academy of the Basque language] (Reference Euskaltzaindia1991–2005), Hualde and Ortiz de Urbina (Reference Hualde and de Urbina2003), and de Rijk (Reference de Rijk2008) can be included. In these grammars onomatopoeia is either not discussed in detail or not mentioned at all.

Finally, a third period covers the last fifteen years, during which several reference works and linguistic studies have been published. To date, there are two dictionariesFootnote 3 , one Basque-English-Spanish (Ibarretxe-Antuñano Reference Ibarretxe-Antuñano2006a), and one Basque-Basque (Santiesteban Reference Santisteban2007), and at least three in-depth studies that offer detailed descriptions of onomatopoeic elements in Basque (Coyos Reference Coyos2000; Ibarretxe-Antuñano Reference Ibarretxe-Antuñano2006b, Reference Ibarretxe-Antuñano2012). Onomatopoeias are also included in the most recent published Basque grammar, the Sareko Euskal Gramatika (Salaburu, Goenaga, and Sarasola Reference Salaburu, Goenaga and Sarasola2011), an on-line comprehensive grammar of the Basque language [www.ehu.es/seg].

2.1 Phonetics, phonology, and prosody

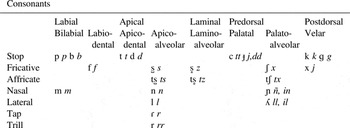

One strategy used in the formation of ideophones is their tendency to employ unusual phonology (either by using specific phonemes, or using the same phonemes for ideophonic and non-ideophonic words, but in different phonotactic environments) and prosody that sets them apart from other words in the language. Basque ideophones have phonemesFootnote 4 that seem to appear exclusively in this type of words, such as the voiced lamino-alveolar affricate /dz/ dz, as well as phonemes and clusters that seldom occur in the same positions in the rest of the lexicon, such as word-initial affricates (tz- /ts̻-/, tx- /tʃ-/) and word-initial palatals (tt- /c-/, ñ- /ɲ-/, x- /ʃ-/) (Hualde Reference Hualde1991: 12). There are also phonemes that, despite being common in the lexicon nowadays, tend to appear in non-native words or recent borrowings, such as word-initial plosives (p- /p-/, b- /b-/, t- /t-/, d- /d-/, k- /k-/, g- /ɡ-/), the labio-dental fricative f- /f-/, the voiceless laminal alveolar fricative z- /s̻-/, nasals (m- /m-/, n- /n-/), and word-initial clusters formed by plosives or f /f/ and liquids (Trask Reference Trask1997: 258; see also Morvan Reference Morvan1996: 184–185, 238–239). These phonological features, with examples, are summarised in examples (1) to (3).

-

(1) Word-initial phonemes

-

a. Affricates:

dz- /dz-/ dzanga ‘dive’

tx- /tʃ-/ txart-txart ‘punish’

tz- /ts̻-/ tzillo-tzallo ‘shuffle’

-

b. Plosives:

p- /p-/ pil-pil ‘simmer; snowflake’

b- /b-/ bolo-bolo ‘spreading’

t- /t-/ tauki-tauki ‘hammering; palpitation’

d- /d-/ di-da ‘beat; proceed’

tt- /c-/ ttirri-tturru ‘trill; warbling’

-

c. Fricatives:

f- /f-/ firri-farra ‘spinning wheel; foolishly’

x- /ʃ-/ xinta-minta ‘whining; whispering’

z- /s̻-/ zingulu-zangulu ‘shuffle’; zurrust ‘swallow, gulp’

-

d. Nasals:

m- /m-/ marmar ‘whispering, mumbling’

n- /n-/ nistiki-nastaka ‘hodgepodge, jumble’

ñ- /ɲ-/ ñir-ñir ‘gleam, twinkling’

-

-

(2) Consonant clusters in onset position

-

a. Plosive + liquid:

plasta-plasta ‘crashing down’ bro-bro ‘boil hard’

tlak ‘sound of mill’ blin-blan ‘staggering’

kluka-kluka ‘in gulps’ grik-grak ‘crackling’

-

b. f + liquid:

flisk-flask ‘crack’; frasta frasta ‘stride’

-

-

(3) Consonant clusters in coda position

-

a. Liquid + plosive

zirt-zart ‘slashing; crackling; shine’

-

b. Sibilant + plosive

drisk-drask ‘violent action’

-

c. Nasal + plosive

dint ‘strongly’

-

Another phonetic characteristic of Basque ideophones is that they are often palatalised (dd /ɟ/, ll /ʎ/, tt /c/, ñ /ɲ/) as illustrated in (4).

-

(4) dd alanddal ‘totally full’ ll apa-llapa ‘slurp down’,

tt apa-ttapa ‘walk with small steps’ ñ ir-ñir ‘gleam, twinkling’

Palatalisation is not restricted to ideophones, in Basque. There are, in fact, two types of palatalisation in this language: conditioned or automatic palatalisation and affective or expressive palatalisation (see Michelena Reference Michelena1985: Ch. 10, Hualde and Ortiz de Urbina Reference Hualde and de Urbina2003: 37–40, de Rijk Reference de Rijk2008: 13–15). Conditioned palatalisation, which varies across dialects, generally occurs in contexts where /n/, /l/, and /t/ are preceded by /i/ as in oinatz /oɲáts̻/, ilargi /iʎárɣi/, and amaitu /amáicu/. Affective or expressive palatalisation, which is reflected in the orthography of Standard Basque, is a productive mechanism to create diminutives (sagu ‘mouse’ and xagu ‘little mouse’), augmentatives (txakur ‘dog’ and zakur ‘big dog’), and affective words, both with a despective and positive meaning (txerri ‘pig’ and zerri ‘swine, hog (insult)’; gozo ‘sweet’ and goxo ‘very sweet, pleasant, nice’).

Mimetic vowel harmony (see Akita et al. Reference Akita, Imai, Saji, Kantartzis, Kita, Frellesvig and Sells2013) is also found in Basque ideophones, as shown in (5).

-

(5) balan-balan ‘move clumsily’ brasta-brasta ‘walk quickly’

farra-farra ‘continuous, rhythmic action’ plasta-plasta ‘crashing down’

terrent-terrent ‘stubbornly’ taparra-taparra ‘walk fast’

traka-traka ‘walk, trot; moving train’ triki-triki ‘walk slowly’

zurrumurru ‘rumour, whisper, gossip’ zorro-zorro ‘snoring, fast asleep’

Some authors (Childs Reference Childs, Hinton, Nichols and Ohala1994a, Dingemanse Reference Dingemanse2011) have suggested that phonological (vowel and tonal) disharmonyFootnote 5 can be associated from a sound-symbolic viewpoint with ‘irregularity’. This might be true in some ideophones in Basque. For example, compare balan-balan ‘move clumsily’ and ‘tumbling, toppling’, taparra-taparra ‘walk fast’ and ‘run with difficulty’. However, it seems that this sound-symbolic contrast between vowel harmony and non-vowel harmony ideophones does not apply in every case. For instance, all the ideophones in (6) seem to have the same meaning, ‘walk slowly, in small steps’, despite vowel differences. Therefore, the whole explanation calls for further investigation.

-

(6) taka-taka, tteke-tteke, tiki-tiki, (t)toko-(t)toko, (t)tuku-(t)tuku, tiki-taka

The number of syllables in these words has also been described as a general characteristic. Ideophones can be monosyllabic and polysyllabic, and on some occasions, they show syllabic patterns different from those common in the language (van Gijn Reference van Gijn2010). In the case of Basque, the number of syllable varies as illustrated in (7). One-, two-, and three-syllable ideophones are the most frequent; four-, and even five-syllable items are also found, though more rarely.

-

(7)

-

a. bar-bar ‘gulp’; plaust ‘sound of heavy object falling’

-

b. arrast ‘drag’; giri-giri ‘dive, swim’

-

c. firristi-farrasta ‘work carelessly’; zipirti-zaparta ‘left, right, and centre’

-

d. barranbila-birrinbala ‘noise, racket, din’; zinkurina-minkurina ‘complaints, groans’

-

e. tibiribiri-tibiribiro ‘chattering away’

-

Finally, another trait of these words is the presence of phonesthemes, that is, sounds that suggest a certain meaning. This is an area that deserves more empirical and experimental research, but there are some clear cases. For example, velar plosives are related to swallowing and gulping as in (8).

-

(8) gurka-gurka, glu-glu, klik-klak, zanga-zanga, zarga-zarga

The place of articulation in vowels seems to indicate different degrees of the same action or event. For instance, different degrees (types) of boiling are related to the vowel used; back vowels are linked to strong boiling (bor bor), central vowels to normal boiling (gal gal), and front vowels to superficial boiling (pil pil). Trills/flaps and sibilants are very important for describing motion events. In dragging events these sounds are often accompanied by the vowels /a/ and /e/, as in arrast egin, herrestatu, narratu ‘drag’, karraka, tarra-tarra ‘drag oneself’, and terrel-terrel ibili, terrest-merrest ‘shuffle’. In sliding and gliding events, on the other hand, trills/flaps tend to occur with the vowel /i/ as in irrist egin ‘slide’, zirin-zirin ‘slide down a slope’, and zirristatu ‘slip’.

The most comprehensive description of phonesthemes in Basque is Coyos’ (Reference Coyos2000) analysis for Suletin Basque ideophones. His proposal, based on Fónagy's (Reference Fónagy1991) framework, includes examples like those summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Some examples of Coyos's (Reference Coyos2000: 78–82) Basque phonesthemes

2.2 Morphology

One of the characteristics of ideophones is reduplication, that is, the full or partial repetition of a morph. This feature is also found with Basque ideophones. There are numerous cases of total reduplication as illustrated in (9), and even triplication (see Rai et al. Reference Rai, Bickel, Banjad, Gaenszle, Lieven, Paudyal, Rai, Rai, Stoll and Yadava2005) as in (10).

-

(9) dzarra-dzarra ‘scribble, doodle’

gurka-gurka ‘in gulps’

nir-nir ‘twinkle’,

trinkulin-trinkulin ‘staggering, tottering, reeling’

-

(10) draka-draka-draka ‘horse galloping’

fil-fil-fil ‘fall down in circles and slowly’

ter-ter-ter ‘in a straight line’

za-za-za ‘speak fast’

Partial reduplication is also very common. Here, the second morph shows different types of both vowel and consonant alternations, that is, the use of one or more different vowels in the second morph, the use of one or more different consonants in the second morph, and consonant insertion, that is, the addition of an ‘extra’ consonant in the second morph, as illustrated in (11), (12), and (13), respectively. There are even cases where all these strategies are used at once as in (14).

-

(11) klik-klak ‘swallow’ pilpil-pulpul ‘palpitation’

binbili-bonbolo ‘gently; ding-dong, peal, ringing; rocking’

-

(12) fits-mits ‘speck’ piko-miko ‘detail’

xirimiri ‘small jobs; drizzle’

-

(13) aiko-maiko ‘fuss; excuse; doubt’ uzkur-muzkur ‘idle’

arret-zarret ‘zig-zag; in any case’ inura-banura ‘indecisive’

-

(14) ingla-mangla ‘sign of sadness’ ziltzi-maltza ‘mess’

2.3 Syntax

Ideophones can fulfill different functions in a sentence. This is perhaps one of the most controversial issues among ideophone scholars, whether they form a category of their own (Doke Reference Doke1935, Awoyale Reference Awoyale1989, Kabuta Reference Kabuta, Erhard Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001), or are instead included in traditional word classes such as noun, verb, adverb, and so on (Amha Reference Amha, Erhard Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001, de Jong Reference de Jong, Erhard Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001).

In Basque, the vast majority of ideophones can function as adverbs and nouns, many as verbs, and to a much lesser extent, adjectives and interjections. Ideophones sometimes need to undergo morphological processes such as derivation (e.g., irrist + -tu verbal suffix: ‘to slide’) and compounding (e.g., irrist + egin ‘make, do’ support verb: ‘to slide’) in order to be included in these categories. This is obligatory in the case of verbal ideophones, but it is also common in other categories. The morphological processes found in each category are listed in (15)–(19), with examples of each.

-

(15) Nouns: Derivational suffixation:

-

a. Ideophone + -ada ‘action, result’

dzistada ‘spark, flash of lightning’

-

b. Ideophone + -ako ‘action, result’

xinkako ‘push, shove’

zanpako ‘gulp’

-

-

(16) Adverbs: Derivational suffixation:

-

a. Ideophone + -ka ‘iterative, manner’

garra-garraka ‘rolling around’

pirritaka ‘rolling’

-

b. Ideophone + case (-n, locative; -z, instrumental)

firrindan ‘quickly’

narraz ‘dragging’

-

-

(17) Verbs: Derivational suffixation:

Ideophone + -tu

dunduratu ‘echo, resound’

sastatu ‘stab’

-

(18) Verbs: Compounding:

-

a. Ideophone + egin ‘make, do’

tart egin ‘snap’

-

b. Ideophone + ibili ‘walk, activity’

pinpili-panpala ibili ‘tumble around’

-

c. Ideophone + egon ‘stative be’

kuli-mulika egon ‘not to have too much work’

-

-

(19) Adjectives: Derivational suffixation:

Ideophone + -tsu ‘having, abundant in’

zarraparratsu ‘noisy’

zizkolatsu ‘shrill’

In other cases, ideophones can stand by themselves without taking further elements; these I call bare ideophones. Verbal ideophones cannot be bare, but ideophone interjections must be. The examples in (20) illustrate these bare ideophones.

-

(20) Bare ideophones

-

a. Nouns:

gur-gur ‘stream; groan’

pilpil-pulpul ‘palpitation’

triki-traku ‘mess, jumble’

-

b. Adverbs:

traka-traka ‘trotting’

trinkilin-trankulun ‘swinging’

-

c. Adjectives:

bri-bri ‘shiny’

gexa-mexa ‘weak’

pinpili-panpala ‘favourite’

-

d. Interjections:

blaust! ‘bam!’

flost! ‘splash!’

panp! ‘sound of falling’

-

Despite the inclusion of Basque ideophones in traditional word classes, it is important to bear in mind that on some occasions, (bare) ideophones are multicategorial, that is, they can be taken, for instance, as nouns and adverbs at the same time. In these cases, the choice of the right word class solely depends on contextual factors. For example, the ideophone traka-traka can be a noun, ‘trot’, or an adverb, ‘trotting’, as shown in example (21). Examples are taken from the Royal Academy of the Basque Language's Orotariko Euskal Hiztegia (oeh) (www.euskaltzaindia.net/oeh).

-

-

(21) a. Traka-traka, zaldi gain-ean Durango-n ziar

traka-traka horse top-loc Durango-loc through

‘Trotting, on his horse, through Durango’

-

b. Jabe-ari baimen-ik eska-tzeke, traka-traka bizi-xamarr-ean

owner-dat permission-par ask-without traka-traka lively-quite-loc

joan zan

go.prf aux

‘Without asking his owner for permission, [the donkey] left with a lively trotting’

-

2.4 Semantics

In languages with a large ideophonic inventory, ideophones are related to specific semantic fields. In Basque, ideophones are found in the semantic areas described in (22)–(30).

-

(22) Actions and events

-

a. Motion: tzainku-tzainku ‘limp’; antxintxi egin ‘run’

-

b. Communication: xuxu-muxu ‘whispering’; zitzipatza ‘verbosity’

-

c. Light: nir-nir egin ‘shine’; zirrinta ‘ray, beam’

-

d. Sound: brinbraun ‘clang’; dilin-dolon ‘ding-dong’; zirris-zarraz ‘sound of sawing’

-

e. Ingestion: lafa-lafa ‘gnawing’; zurga-zurga ‘drink in gulps’

-

f. Destruction: birrin-birrin ‘devastate, tear’; sisti-sasta ‘sting’

-

g. Hitting: blisti-blasta ‘slapping’; furrust-farrast ‘roar’; panpa-panpa ‘hit continuously’

-

h. Boiling: gal-gal ‘boil’; txil-txil ‘soft boiling’

-

i. Emotions: irri egin ‘laugh’; intziri-mintziri ‘sob’

-

j. Bodily functions: pilpil-pulpul ‘palpitate’; pirri-pirri ‘diarrhea’

-

k. Miscellany: bil-bil egin ‘wrap tightly’; sorki-morki ‘sew clumsily’; firristi-farrasta ‘work carelessly’

-

-

(23) Animals

-

a. Insects: burrun burrun ‘bumblebee’

-

b. Crustaceans: karramarro ‘crab’

-

c. Birds: bili-bili ‘duck’

-

d. Amphibians: klunklun ‘toad’

-

e. Fish: perpelete ‘gilthead’

-

f. Others: igiri-migiri ‘otter’

-

-

(24) Plants: txantxar ‘henbane’; ziza ‘mushroom’

-

(25) Weather: xirimiri, zirzira ‘drizzle’; xixta-mixta ‘lighting’

-

(26) Musical instruments: dunbala ‘drum’; txintxirri ‘rattle’

-

(27) Characteristics

-

a. Physical: bonbili ‘fat’; farras ‘slovenly’

-

b. Psychological: kokolo-mokolo ‘idiot’; sinkulin-minkulin ‘wimpy’

-

-

(28) Gadgets: garranga ‘hook, bait’; firinda ‘pulley’

-

(29) Things

-

a. General: kiribil ‘spiral’

-

b. Low value: tunt ‘not a thing’; tzirtzil ‘unimportant thing’

-

-

(30) Other

-

a. Child language: txitxi ‘meat’; mau-mau ‘eat’; ttotto ‘dog’

-

b. Quantity: barrasta-barrasta ‘profusely’; dalan-dalan ‘full’

-

c. Nature: brenk ‘precipitous mountain’

-

d. Sexual terms: txitxil ‘penis’

-

e. Miscellaneous: kinkirrinkon ‘champagne’

-

2.5 Pragmatics

As far as pragmatics is concerned, ideophones have been said to fulfill two main functions: a dramaturgic or expressive function and a stylistic function (Noss Reference Noss, Erhard Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001, Nuckolls Reference Nuckolls, O'Neil, Scoggin and Tuite2006, Webster Reference Webster2009, Dingemanse Reference Dingemanse2011). Basque ideophones fulfill both of these. They are key elements for the dramaturgic function, since they add expressiveness to the discourse, as shown in example (31).

-

(31) Upel-a oso-oso-rik atzaparr-etan artu ta zanga, zanga!

barrel-abs full-full-part paw-loc take.prf and zanga zanga

ustu arte

empty.prf until

‘He grabbed the barrel with his paws and zanga, zanga! until it was empty’ (OEH)

There are a couple of points to bear in mind about (31). The ideophone not only describes the drinking event in a very expressive and vivid way, but also takes the place of a possible verb ‘to drink’. This is very typical for ideophones, as Nuckolls brilliantly explains for Pastaza Quechua:

Although this description [an example] is lacking any finite verb, the ideophones themselves assume the pragmatic importance of verbs. […] In discourse, ideophones are a likely locus of intonational and gestural foregrounding, which contributes to their pragmatic status as performance. […] They capture what is aesthetically salient and absolutely true, what is emotionally riveting and objectively factual. Insofar as they do this, they are pragmatically quite different from the occasional whimsical ideophones used in English such as ka-ching, or bling bling.

Nuckolls (Reference Nuckolls, O'Neil, Scoggin and Tuite2006: 40–41)Ideophones are very often accompanied by gesture, which may add even more expressiveness to the description of the event and, therefore, enhance their dramaturgic function (Kita Reference Kita1993, Moshi Reference Moshi1993, Dingemanse Reference Dingemanse2013). This is also the case in Basque, as illustrated in example (32) and Figure 1:

-

(32) Aoztarr-ek hartu dau txakurr-a gain-ean eta plisti plasta,

Aoztar-erg take.prf aux dog-abs top-loc and plisti plasta

plisti plasta, urten dira erreka-tik

plisti plasta exit.prf aux river-abl

‘Aoztar [a boy] puts his dog on his shoulders and they come out the river plisti plasta plisti plasta’ [B20e2]

The speaker repeats the ideophone plisti plasta twice and synchronises each morph with the upward/downward hand movement (see Ibarretxe-Antuñano Reference Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004).

Figure 1: Ideophones and gesture in Basque

Ideophones also fulfill a stylistic function. They are said to be crucial for the aesthetic content of the text (Noss Reference Noss, Erhard Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001, Nuckolls Reference Nuckolls, O'Neil, Scoggin and Tuite2006, Webster Reference Webster2009, Dingemanse Reference Dingemanse2011). In Basque, the use of ideophones in songs and poems, both traditional (see de Lecuona Reference de Lecuona1964) and modern, is very common. Ideophones are marked in italics.

-

(33) Baga, biga, higaOne, two, three

laga, boga, segafour, five, six

zai, zoi, beleseven, eight, crow

harma, tiro, pum!gun, shot, bang!

Xirri sti-mirristiAbracadabra

gerrena, platgrill, plate

olio zopaoil soup

kikili saldachicken broth

urrup edan edo klik… sip or gulp…

Ikimilikiliklik!Gulp down!

-

(34) Trinkili trankala ari gara

trinkili trankala betikoan

trinkilik trankala

trankalak trinkili

bizitza bideko

egunen orduen

uneen ritmoan.

Trinkili trankala bizi gara

betiko trinkili

-trankal trajiko

majiko

sorpresa

handiko bidaia

bizitza beteko

noiznahikoan tranbala.

The traditional poem/song in (33) includes several examples: xirristi-mirristi ‘magic formula (abracadabra)’, kikili ‘cock’, urrup ‘sip’, klik ‘gulp’, and ikimilikiliklik ‘gulp’. The contemporary poem by the Basque poet Bitoriano Gandiaga (Adio, Reference Gandiaga2004: 93) in (34) contains different versions and repetition of trinkili trankala ‘move noisily, with difficulty’, and tranbala ‘swing’. This poem describes the path of life, full of (un)expected events and changes. The use of these ideophones reinforces the rhythm and pace of life.

Ideophones can frequently be found in comics, as shown in examples zanga zanga ‘drink in gulps’, zapla ‘slap, hit, thud; suddenly’, and marmar ‘whispering, mumbling, grunting’, in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Comics and ideophones (Nepartheid; Patxi Gallego; Patxi Huarte ‘Zaldi Eroa’)

Finally, ideophones play an important role in branding (Klink Reference Klink2000, Reference Klink2003; Yorkston and Menon Reference Yorkston and Menon2004; Shrump et al. Reference Shrump, Lowrey, Luna, Lerman and Liu2012; Velasco et al. Reference Velasco, Salgado-Montejo, Marmolejo-Ramos and Spence2014). Although this is an area that needs more research, it seems that nowadays, there is a clear and growing tendency to name different types of business, and even logos and associations, after these ideophones. Sometimes, the ideophone is chosen on the basis of its relation to the business. In such a case, different strategies are followed. In some cases, the ideophone can simply metonymically refer to some aspect related to the activity of the business. For example, in Figure 3, the ideophone ttipi-ttapa ‘walk in small steps’ is the name of a podiatry clinic and the ideophone xurrut ‘sip’ is the name of a pub. In these cases, the ideophone picks up a relevant feature of the business: walking is the activity that we carry out with our feet and in a podiatry clinic they take care of our feet, and drinking is the main activity that we do in a pub.

Figure 3: Branding and ideophones: xurrut, ttipi-ttapa

In other cases, the ideophone is not only related to the business activity but also adds up to some specific, usually positive, connotation, that serves as a good strategy for luring possible clients in. In Figure 4, the ideophone polpol, which literally means ‘water babbling’, is the name of a pub, referring to the atmosphere that you can find in this pub. It is telling you that this is the right place not only for a good drink but also a lively place to meet your friends. The ideophone dizdiz ‘shine’ is the name of a shop that sells both women's clothes, especially plus-size clothes, and accessories including costume jewelry. The ideophone diz-diz is, of course, related to jewelry, since jewels diz-diz ‘shine’, but it also refers to the result of using the garments sold at this shop. A woman that dizdizes or, as it will be expressed in Basque, an emakume distiratsu-a (woman shiny-det) is a woman that is attractive and pleasing in appearance.

Figure 4: Branding and ideophones: polpol, dizdiz

On still other occasions, the ideophone is selected not only for its relationship with the object but also for the possible expressiveness it adds. In short, ideophones function as dramaturgic as well as stylistic devices. They are considered very catchy words, as shown in the examples in (35). These are mottos for some of the festivities (Ibilaldi 2003, Araba Euskaraz 2013) organised in favour of the Basque Language:

-

(35)

-

a. Dzanga geu-re-ra

dzanga we.int-gen-all

‘Dive into us’

-

b. Mihi-an kili-kili, euskara-z ibili

tongue-loc kili-kili basque-ins walk.prf”

‘Tickle your tongue and live in Basque’

-

Figure 5: Mottos and ideophones

3. Basque ideophones in a typological perspective

One of the most common reasons given for treating ideophones as unimportant linguistic elements is their supposed elusive nature. That is, unlike other categories, these “microscopic sentence[s]”, as Diffloth (Reference Diffloth, Peranteau, Levi and Phares1972: 444) described them, are difficult to characterise from a cross-linguistic viewpoint since they behave differently from other words, but not exactly the same in all the languages with large repertoires of ideophones. It is true that ideophone researchers have not yet reached agreement on crucial issues such as their syntactic nature: do these words form an independent category of their own (Doke Reference Doke1935, Awoyale Reference Awoyale1989, Kabuta Reference Kabuta, Erhard Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001), or are they integrated in other word categories (Amha Reference Amha, Erhard Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001, de Jong Reference de Jong, Erhard Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001)? Are they syntactically integrated or do they stand aloof (Kunene Reference Kunene, Erhard Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001)? But, despite all these controversies, what seems to be clear is that these microlinguistic units stand out in their respective languages: they are foregrounded. They might not be exactly the same cross-linguistically, but they do share certain characteristics. And their differences may turn out to be just a question of degree (Dingemanse and Akita Reference Dingemanse and Akita2016).

In the previous section, I have described some of the main properties of Basque ideophones. In this section, I compare this description with what is known about the linguistic characterisation of ideophones from a typological perspectiveFootnote 6 . This typological comparison will not only situate Basque ideophones in a typological context but also indicate which areas could be further developed in future studies. Each of the tables focuses on one linguistic area—phonetics, phonology, and prosody; morphology and syntax; semantics and pragmatics. Each feature is illustrated with an example from the literature and, where applicable, a Basque example. The presence of a given feature in Basque is indicated by ✔, and the absence of a given feature by ✘. The possible but uncertain presence of a feature is indicated by ?

Table 2: Typological characteristics: Phonetics, phonology, and prosody

Table 3: Typological characteristics: Morphology and syntax

Table 4: Semantics and pragmatics

4. Conclusions and further research

This article has proposed a linguistic characterisation of Basque ideophones from a typological perspective. The main linguistic characteristics of the Basque ideophonic system are: reduplication (total, partial, triplication), unusual phonology and prosody, phonesthemes, multicategoriality, specific semantic fields, and dramaturgic and stylistic functions. All of these characteristics are shared with other languages with similar ideophonic inventories. There are, however, other typological features that seem not to be relevant for Basque, namely, tone variation and harmony, special morphological marking, special phrase/clause position, and usage as grammatical and discourse markers.

There are still several areas in the study of Basque ideophones that deserve further research. From a descriptive perspective, there is no information about the role of prosody in relation to Basque ideophones. Some authors (Fortune Reference Fortune1962, Childs Reference Childs, Hinton, Nichols and Ohala1994a, Nuckolls Reference Nuckolls1996, Kita Reference Kita1997, Jendraschek Reference Jendraschek2002, Kruspe Reference Kruspe2004, Le Guen Reference Le Guen2012, Reiter Reference Reiter2012, among others) have shown that ideophones are usually not only intonationally marked by means of changes and/or special characterisation of features such as pitch, rate, lengthening, intonation breaks, etc., but also phonationally foregrounded by the use of specific phonation features (creaky voice, breathy voice, etc.) (see Childs Reference Childs, Hinton, Nichols and Ohala1994a, Mihas Reference Mihas2012). It is not known whether Basque ideophones also exhibit some of these prosodic characteristics.

Another area that deserves deeper analysis is the syntax of ideophones and their degree of syntactic integration depending on their expressiveness. It seems that Basque follows Dingemanse and Akita's (Reference Dingemanse and Akita2016) inverse relation between expressiveness and syntactic integration; that is, the more expressive the ideophonic form is, the less syntactically integrated it appears and vice versa. In relation to this point, another issue that needs more research is the degree of usage and lexicalisation in Basque ideophones as well as the native speakers’ perception of their ideophonic nature. Basque has both bare ideophones (tipi-tapa ‘to walk in small steps’) and morphologically derived ideophones (dzistada ‘spark’). The former are usually identified with certainty as ideophones by native speakers, whereas the latter are more lexicalised, and therefore, less categorically included in this group of words by native speakers, despite their salient expressive nature. These are good candidates to illustrate the process of “deideophonization” (Msimang Reference Msimang1987). Some of these linguistic forms are very frequent and common in everyday language (burrunba ‘thunder’, irristatu ‘to slide’). Some others have even been adapted and borrowed in neighbouring languages such as Spanish. For instance, the Dictionary of the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language <http://www.rae.es/recursos/diccionarios/drae> includes words such as sirimiri ‘drizzle’ (Basque zirimiri (txirimiri)) and pilpil ‘sound of boiling water’ (Basque pil-pil) → bacalao al pil pil ‘cod in pil-pil (olive oil and garlic) sauce’. Similar situations are reported by Childs (Reference Childs1994b) and Le Guen (Reference Le Guen2012) for Krio and Yucatec Maya in relation to Liberian English and Spanish, respectively. These questions remain largely underexplored in Basque.

The importance of sociolinguistic factors in the usage of ideophones also merits more attention. Childs (Reference Childs1996, Reference Childs, Spears and Winford1997, Reference Childs and Verma1998, Reference Childs, Erhard Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001), among others, has argued that ideophones are sociolinguistically marked words. It seems that in Basque, older and rural speakers tend to make use of ideophones more often in their discourse than do younger and urban speakers, but this is an open question for research.

Finally, the acquisition of ideophones both in L1 and L2 is another virgin area for research. Ideophones are mentioned in the teaching curriculum for Basque as an L2 in levels B2 and C1 in the Lexicon and Word Formation Skills. However, it is still an open question how and how much these words are actually taught. They are treated as mere pieces of vocabulary to be taught to advanced and proficient students of the language. However, if it is true that ideophones are fundamental to the Basque linguistic system, a case can be made that they should be not only taught before those levels, but also treated as key pieces in the organisation of discourse. As far as the L1 is concerned, children's books include more and more ideophones in their pages, and recently, there have been some publications for parents, especially for those who do not speak Basque, that try to help them using some basic words for children with a special emphasis on ideophones (e.g., the booklet published by the Centre for Basque Services in Bizkaia, Ku-ku! Haurrekin hitz egiten hasteko (2006) ‘Ku-ku! Start to speak with children’).

I have shown that ideophones, far from being a rare phenomenon in Basque, are indeed an organic and crucial part of the Basque linguistic system. They share several typological characteristics with ideophones in other languages around the globe and they are certainly an interesting and still underexplored treasure for future research in Basque linguistics.