Introduction: Canada’s 150th Anniversary in the ‘Era of Reconciliation’

The governments of Canada and the Provinces/Territories have long been criticized for failing to negotiate or recognize treaties and to uphold Aboriginal rights and title. Despite this failure, Canada has proclaimed its entrance into an ‘era of reconciliation’ (T. Hunter Reference Hunter2016), while dually celebrating its 150th anniversary as a self-governing colony in 2017. Canada’s sesquicentennial celebrations took place despite sui generis Aboriginal rights continually being disregarded, distinct rights based upon Indigenous existence and legal systems being established on the land base that became Canada long before the sovereign imposition of the settler colonial state (Daigle Reference Daigle2016; Henderson Reference Henderson2002). First Nations whose territories are now identified as British Columbia (BC) are particularly impacted by long-standing calls to establish treaty relationships, since treaty-making between the Crown and First Nations was never fully extended to the west (Foster Reference Foster2009; Miller Reference Miller2009). A suite of litigations upholding Aboriginal rights (e.g., R. v. Sparrow, 1990) and title (e.g., Calder v. BC, 1973), along with the entrenchment of section 35 (s 1-4) of the Constitution that recognized and affirmed treaty rights (Department of Justice Canada, 2012), made ignoring First Nations rights to land and self-governance as recognized by Canada’s legal system impossible. Indeed, without the presence of treaties in most of British Columbia, acquisition of and permission to occupy Indigenous lands was never granted by First Nations (Culhane Reference Culhane1998; Roth Reference Roth2002).

While negotiating modern treaties in British Columbia has been considered synonymous with reconciliation by many, what “new relationships” emerge from the modern treaty-making process in British Columbia remains scarcely investigated (notable exceptions include Baird Reference Baird2011; Penikett Reference Penikett2006).Footnote 1 Despite little research on what new relationships result from modern treaties, many First Nations in British Columbia choose, or at least entertain, treaty negotiations as their path forward with provincial and federal governments: sixty-one of the federally recognized 203 First Nations Bands in British Columbia are at various stages of negotiation (British Columbia Treaty Commission 2018).Footnote 2

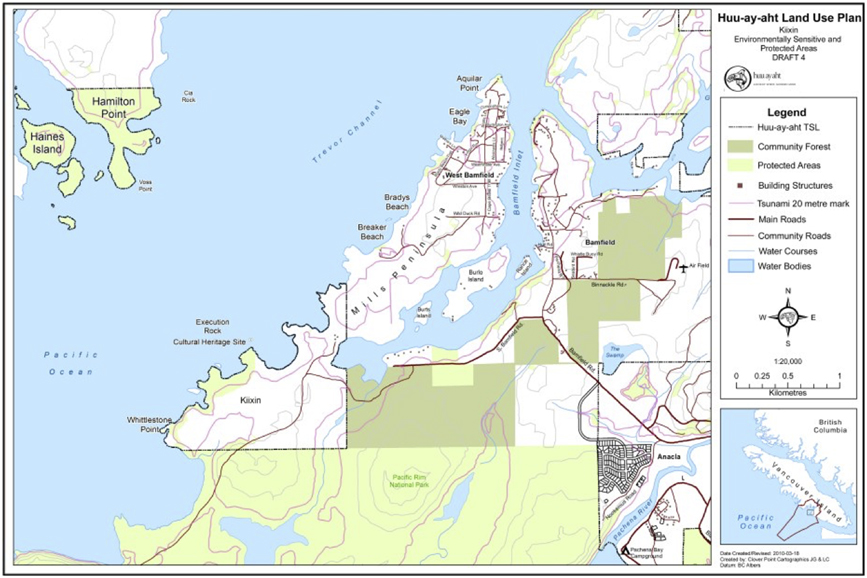

Drawing from a comprehensive case study conducted in partnership with Huu-ay-aht First Nations, a signatory of a recently implemented modern treaty, this paper explores what new treaty relationships look like. We focus on the relationship between Huu-ay-aht First Nations, the Province, and Federal government under the Maa-nulth Treaty, which was implemented on April 1, 2011 (hereafter “effective date”). Huu-ay-aht First Nations is one of five Nuu-chah-nulth signatories of the Maa-nulth Treaty whose traditional territories lie on the west coast of Vancouver Island, specifically the southern Barclay Sound (see Figure 1).Footnote 3 We broadly examine critiques of modern treaties and trace how new relationships under treaties connect to the language of reconciliation in British Columbia. We then shift the focus to our case study. In so doing, we prioritize the voices of participants who are living the new relationship outlined in the Maa-nulth Treaty and of those who implement the agreement from within the federal and provincial governments. Our prioritization of participants’ voices is deliberate and intended to illuminate the main thrust of our manuscript: that modern treaties affect the everyday lives of First Nations signatories and will do so for generations to come. By employing this strategic theoretical approach, we foreground the embodied and lived experiences of “new relationships” implemented under modern treaties. In doing so, we contribute insight into and build from theoretical debates of these agreements to assist communities considering modern treaty negotiations and governments implementing what First Nations have negotiated and agreed upon as their modified rights.

Figure 1 Huu-ay-aht First Nations land use plan, traditional territories, and Treaty Settlement Lands.

Making Modern Treaties: Critiques

The modern treaty-making process in British Columbia has been ongoing for twenty-five years, or since 1993. The British Columbia Treaty Commission (BCTC) is the tripartite overseer of the negotiation process and guides negotiation tables through the six-stage process of negotiation. Since modern treaty negotiations have been underway in British Columbia, seven First Nations at three different treaty tables have successfully implemented their treaties, or reached Stage Six of the six-stage process.Footnote 4 The modern treaty process has been publicly criticized in part for its glacier pace and for the small number of treaties that have been implemented since the BCTC came into effect (Meissner Reference Meissner2016; Sloan Morgan and Castleden Reference Sloan Morgan and Castleden2014). The need to define and outline what has often been shared territories between First Nations as “overlapping claims” is also a major issue of contention (British Columbia Treaty Commission 2014), creating division amongst First Nations due to the incompatibilities between Indigenous governance structures and colonially-derived common law property regimes (Blomley Reference Blomley2003; Mack Reference Mack2009; Thom Reference Thom2008, Reference Thom2009; see also Nadasdy Reference Nadasdy2012).

The loan program for Indigenous Nations to fund their negotiations has also come under scrutiny. Indigenous Nations participate in the negotiation process through combined loans and non-repayable funds allocated by the federal government, the same party that often stalls negotiations at times for years on end. Despite funds for negotiation coming from the federal government and the application of interest on loan repayments, Mack (Reference Mack2009) cites KPMG, a financial consulting firm, who demonstrate that concluding treaties economically benefits Canada and the provinces more so than unsigned treaties (93). In a 2015 report on the comprehensive land claims policyFootnote 5, Douglas Eyford, the Ministerial Special Representative on Renewing the Comprehensive Land Claims Policy, states that since 1973, the outset of the comprehensive claims process, “Canada has advanced in excess of $1 billion to Aboriginal groups through loans and contributions” with upwards of $466 million loaned to Indigenous Nations in British Columbia alone in 2015. Eyford continues, stating that “the debt burden has become an unsustainable barrier to progress” due in part to “the lack of urgency in negotiation,” presumably on behalf of the federal government. Upwards of $10 million in debt exists per negotiation table across Canada (Eyford Reference Eyford2015).Footnote 6

Critiques regarding the ability of treaty negotiations to create conditions for “reconciliation” between federal, provincial, and First Nations sides of the treaty table have arisen. For example, recognizing past injustices experienced at the hand of settler colonial rule is not part of negotiations (Egan Reference Egan2012; Penikett Reference Penikett2006). Indeed, the desire to rectify Aboriginal title in British Columbia, geographers Wood and Rossiter (Reference Wood and Rossiter2011) contend, may rely on “optics of intention” where possessing good intentions “constitutes political capital,” while dually “shifting focus on intent and desire may distract from the actual historical record, which is more complicated than everyday politics can accommodate” (411) (see also Pasternak and Dafnos Reference Pasternak and Dafnos2017). Implemented comprehensive land claims in Canada have resulted in the federal government neglecting its fiduciary duty to Indigenous peoples rather than entering into new and mutually respectful relations (Irbacher-Fox Reference Irbacher-Fox2009). Some scholars and community leaders identify modern treaties as embedded in the colonial politics of recognition, which attempt to legitimate the supremacy and permanence of settler colonial institutions (Coulthard Reference Coulthard2014; Daigle Reference Daigle2016; Diabo Reference Diabo2014) rather than seeking to transform relationships dedicated to redress.

Toquaht legal scholar Johnny Mack (Reference Mack2009) describes how the colonial politics of recognition operated in Maa-nulth Treaty negotiations. Explaining that Indigenous Nations enter the negotiation process to essentially ask for a different relationship with the state, Mack argues that resulting relationships remain steeped in imperial dynamics. The case for this different relationship, Mack continues, is based on two frames: “One source is our own constitution and the rights and responsibilities that flow from it; the second is the normative structure of the state recognition forums.” Within the asymmetrical recognition-based structure of modern treaty negotiations, Mack asserts that “the content of our recognition claim is drawn from the former [frame]; the latter source works to reformulate that content in a manner that the state will comprehend and respond to.” What results is the state’s maintained ability to “decide what aspects of the claim to recognize” (63) both during negotiations and when agreements are concluded.

While criticisms of modern treaties exist, those who choose to enter negotiations with the aim of creating new relationships between First Nations and the provincial and federal governments hold modern treaties as the “highest expression of reconciliation” (British Columbia Treaty Commission 2016a, 2). Below, we trace the language of new relationships in British Columbia, First Nations, and Crown relations to reveal how reconciliation became synonymous with modern treaties by their proponents.

Proposing New Relationships

In 1990, leaders of British Columbia First Nations assembled a Task Force with representatives of Canada and British Columbia to determine what a made-in-BC treaty process could entail, and what the outcome of changing the relationship between federal, provincial, and First Nations governments could involve. The Task Force’s (1991) responsibility was to “define the scope of negotiations, the organization and process of negotiations including the time frames for negotiations; the need for and value of interim measures and public education” (British Columbia Claims Task Force 1991, 29). A year later, the Report of the British Columbia Claims Task Force was produced, outlining what negotiations in British Columbia should look like; it remains the blueprint for modern treaty negotiations in the province.

The need to create a new relationship is outlined in the Task Force’s (1991) report:

As history shows, the relationship between First Nations and the Crown has been a troubled one. This relationship must be cast aside. In its place, a relationship which recognizes the unique place of aboriginal people and First Nations in Canada must be developed and nurtured. Recognition and respect for First Nations as self-determining and distinct nations with their own spiritual values, histories, languages, territories, political institutions and ways of life must be the hallmark of this new relationship. (7)

The made-in-BC treaty process was founded on “the establishment of a new relationship based on mutual trust, respect and understanding—through political negotiations” (British Columbia Claims Task Force 1991, 8). The provincial and federal governments have not always been quick to move forward with attempts to reconcile unjust relations with First Nations through negotiation, however.

Despite the Task Force’s call to create new relationships between the Province of British Columbia, Canada, and First Nations, little conciliatory movement appeared to occur immediately after the release of its report. It was not until the landmark decision in Haida Nation v. British Columbia [2004] upheld the Crown’s duty to consult that the motivation needed for the Province and Canada to start making new relationships occurred (Newman Reference Newman2009). Since the majority of First Nations in British Columbia are not in a treaty relationship with the Crown, legal ‘uncertainty’ surrounding rights to lands and resources emerged (Woolford Reference Woolford2005; also Pasternak and Dafnos Reference Pasternak and Dafnos2017). The Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in Haida [2004] legally affirmed First Nations’ abilities to stalemate the provincial and federal economy if First Nations were not consulted prior to undertaking operations that accessed resources on their territories (McCreary and Milligan Reference McCreary and Milligan2013; also Blomley Reference Blomley1996).

British Columbia’s economy relies on exploiting the natural resources available on Indigenous lands. Indeed, this point was affirmed by the Office of the Premier itself: “resources are what drives British Columbia’s economy and allow us to pay for the services all British Columbians need” (personal communication, November 21, 2014). The Haida decision highlighted the need for the Province to move forward amicably with First Nations and to bridge the social and economic gap between First Nation and settler populations. In 2005, First Nations leaders under the banner of ‘the Leadership Council Representing the First Nations of BC’ met with British Columbia to draft The New Relationship, a document intended to envision how relations could change between First Nations and the Province, and what the priorities of each party were, with specific focus on socio-economic inequities (Government of British Columbia and The Leadership Council Representing the First Nations of British Columbia 2005).Footnote 7 Months later, the government of Canada joined the conversation and, together with the Government of British Columbia and the Leadership Council Representing the First Nations of British Columbia, they collectively penned the Transformative Change Accord.

The Transformative Change Accord outlined how The New Relationship document would be realized, while looping the government of Canada into the new relationship; it committed British Columbia and Canada “to achiev[ing] strong governments, social justice and economic self-sufficiency for First Nations which will be of benefit to all British Columbians and will lead to long-term economic viability” (Government of British Columbia, Government of Canada, and The Leadership Council Representing the First Nations of British Columbia 2005, 1). The parties were thus locked into working together to close “the social and economic gap between First Nations and other British Columbians over the next 10 years, of reconciling [A]boriginal rights and title with those of the Crown, and of establishing a new relationship based upon mutual respect and recognition” (2005, p. 1, emphasis added).

The language of reconciliation has long intersected such new relationships. The release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s ninety-four calls to action in 2015 undoubtedly amplified reconciliatory language. For example, the 2016 Annual Report of the BCTC links the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples with treaty making. It also discusses bridging the economic gap between First Nations and settler parties as “measuring reconciliation” (British Columbia Treaty Commission 2016a, 19). Updates on negotiation tables are termed “Reconciliation Updates,” with treaty negotiations themselves said to “embody reconciliation and the UN Declaration [on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples]” (British Columbia Treaty Commission 2016b). Reconciliatory language that emerges through the treaty process nods to the inability to separate Canada’s colonial genealogy, including the lasting effects of residential schools, from the new relationship between First Nations and settler-colonizing governments. While recognizing that “there is no one pathway to achieve reconciliation” (British Columbia Treaty Commission, 2016a, 2), the BCTC and many who are proponents of the treaty process maintain modern treaties are a favourable route to establish new relationships between the Province, the Federal Government, and First Nations governments.

Case Study: The Nuu-chah-nulth Treaty Table and Signing the Maa-nulth Agreement

The BCTC’s mention of diverse pathways to reconciliation highlights considerations that each First Nations takes when deciding how and whether they want to develop a new relationship with federal and provincial governments. For Huu-ay-aht First Nations, and indeed all five Maa-nulth Treaty First Nations signatories, community members collectively decided to go the path of negotiating a modern treaty. In the section following, we outline how Huu-ay-aht First Nations entered the treaty negotiation process under the collective banner of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council (NTC) through to the implementation of the Maa-nulth Treaty under the administration of the Maa-nulth Treaty Society and each First Nations’ staff and government.

Months after the BCTC began accepting First Nations’ “Statement of Intent to Negotiate” (Stage One of the BCTC process) modern treaties with the federal and provincial governments in 1993, the NTC, on behalf of thirteen of the fourteen Nuu-chah-nulth Nations on the west coast of Vancouver Island, entered the six-stage process. After members of each of the thirteen Nations voted to enter treaty negotiations, the NTC began negotiations in January 1994 (British Columbia Treaty Commission 1996).Footnote 8 After seven years of active negotiations, the NTC had reached Stage Four: an Agreement in Principle (AIP). It was at that point that members of the NTC Nations voted on whether to accept the AIP and move forward to Stage Five: Negotiation to Finalize Treaty. Six of the NTC Nations rejected the AIP and thus rejected moving forward to the next stage of negotiation, while two decided to negotiate at their own treaty table; five NTC Nations voted in favour of moving forward. As a result, the five Nations whose members voted in favour of moving to a Final Agreement formed the Maa-nulth First Nations. An NTC resolution was passed in 2001 allowing the five Maa-nulth Nations to leave the NTC table and move forward with the negotiated AIP (Maa-nulth First Nations 2003).

In 2007, community members of the five Maa-nulth Nations voted on whether to conclude the negotiations and move towards ratifying the Final Agreement, of which all Maa-nulth Nations voted in favour. Eighty percent of eligible Huu-ay-aht First Nations voters cast a ballot; of those, 90% voted in favour (Maa-nulth First Nations 2007b). Thus, after sixteen years of active negotiation and two years of finalizing and truing laws, the obligations of the 320-page Treaty were transformed into Canadian law in 2009 and were implemented by Maa-nulth First Nations’ Governments in 2011.

Research Approach

This paper stems from a five-year community-based participatory research project that seeks to create a comprehensive case study of Huu-ay-aht First Nations’ negotiation and implementation process. Semi-structured interviews, participant observation, community engagement sessions, archival document analysis, a photovoice project, and a citizen survey were used to collect data. The data used for this paper come from the interviews, which were conducted over two years (2015 to 2016) with Maa-nulth Treaty negotiators and implementation teams from all sides of the Treaty table. Below we highlight how we co-designed our interview guide, identified research participants, and analyzed the data to situate our findings within the contemporary social, economic, and political context in British Columbia.

A Huu-ay-aht Advisory Committee guides the project and the research team; we co-created the interview guide to ensure applicability. The Advisory Committee identified key people involved in negotiating and implementing the Maa-nulth Treaty as ideal candidates to recruit for the interviews. Once we received ethical approval from Queen’s University at Kingston, we contacted participants by email, inviting them to take part in a one-hour interview. Once interviews were underway, snowball recruitment techniques were also employed. Of the thirty-five invited to participate, twenty-six completed interviews.

Participants consented to audio or hand recorded interviews, and they were invited to check their transcripts for accuracy, receive preliminary findings for comment, and confirm that the way they were quoted in this paper was acceptable. They had an opportunity to be anonymized or identified with their quotes in dissemination. Of the twenty-six interviews completed, twenty-five participants consented to digitally recorded and one hand recorded interviews, all but three participants reviewed their transcript for accuracy once transcribed, all but one requested the opportunity to review their quotes in context, with none objecting to direct quotations being used, and nineteen wished to be identified with direct quotes.

All interviews underwent inductive thematic analysis using qualitative coding software (NVivo for Mac, QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 11, 2016). Data was descriptively coded under the category “implementation.” Within this category, the data associated with “new relationships” was then analytically coded for “challenges,” “strengths,” and “recommendations.” What resulted was the emergence of three key themes. The Huu-ay-aht Advisory Committee reviewed and approved this approach to analysis in August 2016; they reviewed and approved the manuscript in October 2017 and provided direction on revisions in May 2018. The thematic findings presented below explore: 1) enacting new relations between the Federal Government, Provincial Government, and Huu-ay-aht First Nations at the tripartite table and through Huu-ay-aht First Nations’ administration of self-governance; 2) learning new relationships by federal and provincial governments; and 3) the political will to negotiate and implement new relationships. We present these findings below.

Enacting New Relationships

The “coalface” or “front line” of the new relationship, as phrased by one participant, occurs at the Maa-nulth Tripartite Implementation Table.Footnote 9 Mexsis (Tom Happynook) described the task of the committee as attempting to “circumvent any conflicts, try to deal with any conflicts that come up so that it doesn’t go into the dispute resolution process” (Whaling Ha’wilth, former Maa-nulth Treaty negotiator, former Huu-ay-aht Treaty Implementation Committee Chair, former Huu-ay-aht First Nations Councillor, and current BCTC Commissioner, interview by Sloan Morgan, August 2015). All Treaty signatories have representatives on the Maa-nulth Implementation Committee, and since the Treaty went into effect in 2011, they have been holding face-to-face meetings bi-annually, with additional meetings called on an as-needed basis. Core representatives from Maa-nulth parties have begun convening prior to the tripartite meetings to recap solutions and action items to ensure the official tripartite meetings are as productive as possible. Although the five Maa-nulth Nations negotiated the Treaty collectively, each signed individually, and they have separate governments with their own Constitutions. With the exception of the Maa-nulth Fisheries and Wildlife Committees, each Maa-nulth First Nations implement their self-governance separately from each other.

While each Maa-nulth Nation implements self-governance separately, the federal and provincial governments’ end goals of the treaty as a means of reconciliation and to define new relationships are the same: “…Whereas the Maa-nulth First Nations, the Government of Canada and the Government of British Columbia have negotiated the Agreement to achieve this reconciliation and to establish a new relationship among them…” (Government of Canada 2009).

For over 18 years, treaty negotiators worked intensely with all parties to finalize the Maa-nulth Treaty—to delineate the obligations of each signatory for a new relationship. On the effective date however, relationships changed significantly: “[W]e went from a regular basis, seeing these negotiators from federal and provincial government, but as soon as we signed it, they were all out of our face. And all those discussions stopped, and all the emails stopped... It was kind of like, ‘We’re done, bye, and you guys are kind of on your own’” (ƛiišin [Derek Peters], Huu-ay-aht First Nation’s Tayii Ḥaw̓ił, Interview by Sloan Morgan, May 2016).

Representatives for the tripartite signatories were no longer negotiating, and so while many of the same people were representing the Maa-nulth Nations in the implementation of the Treaty, the Province and Canada had primarily new representatives in place to implement the new relationship under treaty.

The “old relationship,” however, had been dictated by the direction of the federally defined Indian Act for nearly 150 years, and the Provincial government’s exploitation of Indigenous lands for economic gain—indeed, exploitation that occurred before the province was even incorporated (Harris Reference Harris2004). Reflecting on the change of relationship with federal bodies, a participant spoke to difficulties for a bureaucracy as large as the Federal government to transition to a new relationship with First Nations: “the Federal bureaucracy is so entrenched in the Indian Act… I think it’s hard for them to get their minds wrapped around this different relationship” (Mexsis [Tom Happynook], interview by Sloan Morgan, August 2015). A federal representative of the Implementation Branch in Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) discussed the abrupt change in the context of bringing the treaty to fruition: “we spent fifteen years negotiating these things, and then it’s almost as if we kind of expect the treaties to magically work themselves, and they don’t. They require a lot of work” (Implementation Branch Representative, INAC, interview by Sloan Morgan, May 2016).

Huu-ay-aht participants, on four separate occasions, identified the first years of the “new relationship” with the federal government explicitly as being similar to a divorce: “The Federal government treated this Treaty less like a new relationship and more like a divorce paper. ‘Don’t want anything to do with you anymore. It’s not our problem. Here’s some money. Go away.’ That sounds like a divorce to me” (John Jack, elected Huu-ay-aht First Nations Councillor & Alberni-Clayquot Regional District Chair, interview by Sloan Morgan, May 2016). Once treaties in British Columbia go into effect, the federal government transfers files from INAC’s Treaties and Aboriginal Government, Negotiations West, which is based in Vancouver, over to the Implementation Branch, which is located over 4,000 kilometres away in Gatineau, Quebec. There is little overlap during the transition from negotiations and implementation, although self-governance occurs quite literally overnight on the effective date. A participant spoke of British Columbia’s role in implementing the Maa-nulth Treaty as “slightly more conciliatory”: “It wasn’t about ‘Go away.’ It was ‘This is how it’s going to be now. Hopefully that works for you.’ But it was also still ‘This is how it’s going to work for us and this is what we require’” (John Jack, interview by Sloan Morgan, May 2016). British Columbia’s Implementation arm of the Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation (MARR)Footnote 10 is separate from the Ministry’s Negotiations Team. Huu-ay-aht First Nations’ experience of accessing programs and services through the federal and provincial governments exacerbated perceptions that the new relationship was not one of moving forward in a mutually respectful relationship, but rather one of severance.

Provisions in the Treaty state that unless a Maa-nulth Nation has “assumed responsibility for those programs or services under a Fiscal Financing Agreement” (Maa-nulth First Nations 2007a, para 1.9.3), nothing affects Maa-nulth signatories’ eligibility “to participate in, or benefit from, programs established by Canada or British Columbia for aboriginal people, registered Indians or other Indians, in accordance with criteria established for those programs from time to time” (para 1.9.2). Maa-nulth signatories negotiated on the premise that their Treaty would not prevent its signatories from accessing provincial or federal programs that are not included in the Treaty. The first years of implementation proved quite the opposite, however: “For the first year, we felt like there was this big flag on every bureaucrat’s desk in Canada that said, ‘Just say no to Maa-nulth because they no longer qualify for any funding or assistance because they are treaty Nations.’ There seemed to be no will on Canada’s part to explore solutions or assist Maa-nulth Nations in getting firmly on their self-governing feet. We were unable to get even advice on something as basic as preparing emergency plans” (Shii-shii-kwalahp [Angela Wesley], Huu-ay-aht First Nations Treaty negotiator and Maa-nulth Implementation Committee, interview by Sloan Morgan, September 2015).

We end this section with an example to illuminate how the first year of implementing the Maa-nulth Treaty was experienced as severance. Huu-ay-aht First Nations’ main village of Anacla sits in a major tsunami hazard zone. Vancouver Island lies on the fault line of three major tectonic plates and is susceptible to major earthquakes. Huu-ay-aht First Nations has funding provisions allocated in the Fiscal Financing Agreement of the Maa-nulth Treaty for emergency response; however, when Canada was asked for advice on infrastructure options, they refused to provide insight. Canada’s refusal to offer advice at that time reinforced Huu-ay-aht First Nations’ view of the new relationship as a divorce, with the financial package mirroring a division of assets rather than supporting First Nations as they bridge the social and economic gap, despite this role being outlined in The New Relationship and the Transformative Change Accord.

Learning New Relationships

Although self-government provisions, such as emergency response plans, at times left Huu-ay-aht First Nations out in the cold, other indicators were emerging that suggested this new relationship was still being understood within the prescriptions of the Indian Act. For example, three Huu-ay-aht participants reported receiving requests for Band Council Resolutions (BCR) from the Federal government after the effective date—formal notices delivered to INAC outlining decisions made by Band Councils.Footnote 11 Under the Maa-nulth Treaty however, BCRs ceased to be a mechanism for providing instructions or approvals. Instead, Executive Council Resolutions were to be used, which extend from self-governing structures outlined and defined in the Huu-ay-aht First Nations Constitution and Governance Act and were/are not subject to INAC authority.

A participant from the Federal government acknowledged that implementing new relationships from within its bureaucracy at times failed to appropriately recognize changes in First Nations governance. Requests for BCRs are part of a “formulaic correspondence” generated automatically (Implementation Branch representative, INAC, interview by Sloan Morgan, May 2016). Misperception amongst federal (and provincial) bureaucrats on how First Nations self-govern under modern Treaty and relate to the Federal (and provincial) government runs deeper than technical error, though: “A lot of departments weren’t of the view that they actually had responsibilities or weren’t aware of their responsibilities—their individual responsibilities—of the Treaty. They weren’t aware of what we would call ‘cross-cutting obligations’ as well” (Implementation Branch representative, INAC, interview by Sloan Morgan, May 2016).

Legal counsel for the Maa-nulth Nations described the failure to comprehend the shift in relations by providing a hypothetical scenario between provincial and federal staff and Maa-nulth Nations to relay his point: “‘I know the treaty says you can have that, but my policy says you can’t. So I’m not going to.’ And what do you do? So it’s that education, that training and I’m hoping over time that gets better, but I’ll tell you, the first few years have been very challenging with, when policy trumps treaty, something’s wrong” (Brent Lehmann, Maa-nulth Legal Counsel and Implementation Team, Ratcliff & Company, interview by Sloan Morgan, July 2015).

All participants identified a major overarching issue facing treaty signatories’ implementation of a new relationship as being the lack of coherence between governments. Federal departments were largely unaware of the new obligations that they now faced under Treaty; there was an assumption that INAC would be responsible for implementing all aspects of the agreement: “[O]ne of the things that’s important, I think, for people to realize is that our relationship with Maa-nulth and other treaty groups is with the Crown. It’s not with Indigenous Affairs. And we find that most of the actual implementation obligations and relationships and responsibilities rest with many other government departments” (Implementation Branch representative, INAC, interview by Sloan Morgan, May 2016).

Provincial ministries also experienced some degree of disjuncture, failing at times to recognize that treaties are signed by the Province of British Columbia as a whole, not just Ministries:

In a few isolated cases, we have reviewed certain components of the treaty obligations with Ministries and they’ve said, ‘No, your Ministry deals with the implementation of the Treaty. We don’t have a role to do that.’ Our response to that is to provide a context to the issue and direction to them that links that term of the treaty to the roles and responsibilities of their particular Ministry. We let them know that we can help facilitate discussions with Treaty First Nations regarding those terms and that they can provide the necessary expertise to resolve outstanding issues. (Wendy Hutchinson, Director of Implementation and Provincial Maa-nulth Committee, Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation, interview by Sloan Morgan, December 2016).

One notable instance of cross-cutting challenges, which was brought up by nearly every participant, was the federal government’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans’ (DFO) failure to comply with certain provisions of Treaty. Fish, and salmon in particular, are culturally significant to Huu-ay-aht and Nuu-chah-nulth lifeways. The Maa-nulth Treaty has an entire chapter on fisheries. Because salmon is such an important species to Nuu-chah-nulth lifeways, provisions were negotiated for times when sockeye salmon travel east up the Fraser River, rather than west through Nuu-chah-nulth territories. Despite Maa-nulth’s Fisheries Committee following all provisions in the Treaty necessary to harvest their sockeye allocation for domestic purposes through agreements with other First Nations, participants stated that for two years in a row (2014 and 2015) the DFO failed to uphold their Treaty obligation and permit Huu-ay-aht First Nations to move forward with harvesting. A former federal representative first assigned to the Maa-nulth Implementation Table argued that conflict with DFO was not a result of failed treaty obligations, but rather a consequence of Maa-nulth Nations not “fishing hard enough” in their Domestic Fishing Area (first author’s field notes, February 19, 2015).

In 2015, four years after the Maa-nulth Treaty had come into effect, compliance issues, such as fish allocation concerning DFO, were ongoing. In response, the BCTC met with the Federal government to discuss the dysfunction in enacting new relationships: “Our message to them this time was that they needed to bring all of the government departments that are affected by treaty [together] to communicate with each other so they all know what’s going on” (Mexsis [Tom Happynook], BCTC Commissioner, interview by Sloan Morgan, August 2015). Within a month of that meeting, a Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation, also known as the Whole of Government Approach, was released by INAC. The Directive “lays out an operational framework for the management of the Crown’s modern treaty obligations” and “guides federal departments and agencies to fulfill their responsibilities” (Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada 2015). A Deputy Minister’s Oversight Committee was also established to ensure high-level oversight and management of all departmental obligations under treaty. A Treaty Obligation Monitoring System (TOMS) was instituted to track treaty obligations between the thirty federal departments that have responsibilities under comprehensive land claims (Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada 2014), including the Maa-nulth Treaty.

The Province is seeking to improve cross-ministerial obligations under treaty by delivering education and training to all provincial employees on the relevance and impacts of creating new relationships. At the time of writing this article, an internal auditing system—the Automated Treaty Obligation System—was being piloted to outline treaty obligations to demonstrate the whole-of-government impact of treaties. The First Nations Secretariat within the Government of British Columbia was also established to ensure treaty obligations permeate all ministerial levels.Footnote 12 The Secretariat brought treaty related matters during the implementation of the Maa-nulth Treaty, and negotiation matters at other treaty tables, to high-level officials with decision-making authority to problem-solve efficiently. A MARR Director described how the Implementation Team in the Implementation, Land Services Branch helps all ministries understand their responsibilities under treaty: “They [provincial employees] understand that it’s [a request to act on treaty obligations] coming from the executive wing of their Ministry. It’s not just someone’s idea that they’re floating out there. It’s a Cabinet direction, more than a, ‘We’d kind of like you to do something’” (Wendy Hutchinson, MARR, interview by Sloan Morgan, December 2016).

Participants from all sides of the Maa-nulth Treaty table echoed the importance of educating governments about new relationships and obligations outlined in treaties. Indeed, proactive responses can attempt to limit dysfunctional “new relationships” under treaty; MARR’s internal education attempts to provide resources to all ministries about the history leading to modern treaties and the long-term effects, with the purpose of “understanding that you are in the balance, holding that position of reflecting the past and planning for the future” (Wendy Hutchinson, MARR, interview by Sloan Morgan, December 2016). A federal participant furthered the imperative to learn new relationships by identifying that a fundamental shift in the Federal government was needed. Stating “you don’t change the culture of the federal government just by issuing a directive,” they continued: “[The Treaty is] not a contract where you’re battling to kind of do the least you can to fulfill the terms. You have to do the most you can to fulfill the relationship. And it’s not a contractual relationship. It’s a long-term, enduring constitutional relationship. And changing that mindset in the Federal government is something that we’re working on and continue to need to work on” (Implementation Branch representative, INAC, interview by Sloan Morgan, May 2016).

The machinery injected into the federal and provincial governments provides the framework to more effectively enact new relationships under modern treaty. However, doing so will involve more than operationalization. Political will and knowledge of the realities facing Indigenous signatories is key to effective and mutually respectful new relationships.

The Political Will to Create New Relationships

Participants who negotiated the Maa-nulth Treaty reported that electoral changes in political parties over the years of negotiation and implementation created palpable shifts to the “new relationship” approach taken by Canada and British Columbia. The economic priorities of these parties had particularly heavy bearing on negotiations and implementation. The former BCTC Manager of Treaty Negotiations reflected on the importance of political will through Canada’s former Conservative Federal government’s actions during Maa-nulth negotiations: “I would say since the [Conservative Party of Canada’s] government has been in power [2006–2015]—it’s extremely difficult to get to work their treaty agreements through the caucus or through the committees. And I would say that there’s a limited willingness to burn up political capital on treaties if it looks as though they’re going to be controversial…it really does depend on the government in power” (Peter Colenbrander, interview by Sloan Morgan, June 2015).

The lead negotiator for the Maa-nulth Nations furthered comments on political will in terms of addressing conflict and setting priorities:

I think the [Conservative Party of Canada’s] Federal government… has probably addressed [conflict] by trying to figure out how to avoid it or avoid any responsibility for it. That’s the extent of their commitment, but I think that reflects the style of this particular government. When you run an entire government out of one office with a million and one different issues, the only way you can eventually do it is by not addressing any issues and certainly not addressing any issues in any detail. The Federal government appears to be interested in one thing, which is assuring that it gets re-elected and counting its polls to make sure it knows where its votes are. (Gary Yabsley, Lead negotiator [2004–2011], Maa-nulth First Nations, interview by Sloan Morgan, June 2015)

With respect to the BC Government, select issues that the Province and Maa-nulth Nations could not reach an agreement on were punted to side agreement negotiations post-effective date. Language was officially inserted into the Treaty earmarking side agreement negotiations, such as foreshore agreements (e.g., Maa-nulth First Nations, 2007a, para 14.5.1). Once the Final Agreement was reached, however, Maa-nulth participants experienced the diminishing political will of the Province to conclude side agreements. A Huu-ay-aht First Nations Elected Councillor retells: “[T]here hasn’t been a lot of willingness [from BC] into kind of confronting those [side agreements] now. A lot of time has passed, not all the same people are there, but punting allowed us to get to the finish line with not all of the goods, so to speak. It pushed a conflict forward… now we’re at a greater disadvantage the more time we wait” (John Jack, interview by Sloan Morgan, May 2016).

Former elected Chief Councillor of Huu-ay-aht First Nations and Ḥa’w̓iiḥ also recalls: “[O]nce you sign an agreement, [the federal and provincial governments] kind of put you aside, no matter what it is, I guess. It could do with anything out there. But once you sign an agreement, … they forget about you basically, unless it’s in their best interest” (Yaalthuu-a [Jeff Cook], interview by Sloan Morgan, August 2015). Speaking to political will for provincial parties, two Maa-nulth legal-council participants observed that the former (2001–2017) BC (Liberal) Government’s emphasis on the development of Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) created a noticeable lack of resources to treaty tables, including experienced negotiators: “when they’re reallocating people and resources to things like LNG projects, then it’s even harder to find somebody that’s got authority or the time to address the post-treaty problem” (Gary Yabsley, interview by Sloan Morgan, June 2015). Indeed, during the Liberal Party’s term as the Government of BC from 2005 to 2011, there was significant emphasis on treaty negotiations (Rossiter and Wood Reference Rossiter and Wood2005; Wood and Rossiter Reference Wood and Rossiter2011), but since 2012, its focus has been diverted from treaty negotiations to discussion with First Nations and industry in an attempt to move forward with controversial LNG developments (Fowlie Reference Fowlie2013). In response to these challenges, participants suggested options for incremental and alternative agreements between Provincial and First Nations governments, as well as federal level interim agreements. Such approaches were suggested as integral for First Nations to have options available to enact new relationships, in addition to modern treaties.Footnote 13

Discussion

We begin our discussion by exploring why disjunctions in new relationships under treaty arise. Specific challenges to the new relationship created under the Maa-nulth Treaty are provided in the table below; we draw upon issues from the table to illustrate challenges in our discussion but also intend for the table to be a resource for those negotiating and considering the path of modern treaty (see Table 1).

Table 1 Challenges implementing the Maa-nulth Treaty identified by research participants with recommendations for improvement

BCTC: British Columbia Trade Commission; FLNRO: Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations; INAC: Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada.

New relationships created through modern treaties impact signatories on various scales. While federal and provincial governments must manage their own internal operationalization of agreements, Maa-nulth Nations implement their self-government in place of the Indian Act—an Act that has dictated First Nations’ lives on their homelands since 1876. Reflecting on the change towards federally and provincially recognized self-government that occurs in treaty, Humin’iki [Irene Peters], Hakuum [Huu-ay-aht’s Female Royalty] and a former elected Huu-ay-aht Councillor (interview by Sloan Morgan, January 2016), reveals a fundamental disconnect about how the new relationship is experienced by signatories: “[The Indian Act] was our life…. I think that’s where… the emotion stems from and that investment that [the Maa-nulth Treaty] wasn’t only me, that it’s our people too that are… living and breathing it and talking about it and conversations and everything that’s happening every day because this is going to affect our life.” Although modern treaties indeed have “social and economic importance to all British Columbians” (BC Laws 2007), lifting the Indian Act wholly affects future generations of Huu-ay-aht in innumerable ways. Viewed in this light, achieving “mutual respect” (BC Laws 2007) involves understanding the impacts of final agreements through all levels of government that entered into new relationships:

What to keep in mind is that we’re fundamentally changing the relationship with Indigenous people. It’s an enduring relationship that’s going to last forever. And once you kind of put yourself on that plane I think you see the treaty a little bit differently—not as contracts that need to be fulfilled but the basis for a relationship that’s going to endure. And that’s kind of a mindset I think we need to kind of get around. And to me, that’s treaty implementation, [it] is making that Crown relationship work. (Implementation Branch representative, INAC, interview by Sloan Morgan, May 2016)

Grand Chief Ed John of the First Nations Summit, one of the three Principals to the BC Treaty Negotiation Process along with British Columbia and Canada, relays that treaties are negotiated to “establish sets of relationships that set up reconciliation relationships between themselves and the Crown governments. The sad reality is that the people generally are distant from that. They’re kind of indifferent. They have to worry about their day-to-day things” (Grand Chief Ed John, interview by Sloan Morgan, September 2015). From her Huu-ay-aht perspective, Humin’iki echoes this sentiment:

[T]hat’s frustrating because what I see is the amount of effort and the amount of importance it is to the Maa-nulth Nations, but it’s not on the Canada side or the BC side. And still, to them, it’s just paper and policy and process and, ‘I’m sorry. We received your letter today, but we can’t do anything. And we disagree that this is not a dispute.’ … this is supposed to be an improved process and an ability for us to have a tripartite [agreement] so we can all talk about these issues and work about trying to get beyond them, like the Fraser River sockeye salmon, which was negotiated in our Treaty. (interview by Sloan Morgan, January 2016)

The difficult new relationship between the five Maa-nulth Nations and the DFO is illuminated in Humin’iki’s words. She demonstrates how failed treaty relations are experienced by Maa-nulth Nations signatories, despite the new relationship under treaties intending to reconcile First Nations and Crown relations; indeed, virtually all research participants identified the relationship between Maa-nulth and the DFO to be the most dysfunctional aspect of the new relationship. While the failure to uphold Maa-nulth Treaty obligations was eventually addressed by the federal government, to Huu-ay-aht First Nations, the inability of the federal government to act in a timely manner seriously impacted the everyday realties of Huu-ay-aht citizens whose cultural practices and worldviews are deeply intertwined with salmon. This begs the question: how can new relationships be upheld in a respectful and mutually beneficial manner when one treaty signatory views obligations as bureaucratic process and another, a commitment that will impact their children and grandchildren, cultural practices, and everyday lives for future generations?

Critiques of modern treaties both report on but also caution the incompatibility of First Nations’ worldviews and the bureaucratic conditions and structures associated with operationalizing modern treaties, particularly for provincial and federal governments (Mack Reference Mack2009; Nadasdy Reference Nadasdy2003, Reference Nadasdy2017; Thom Reference Thom2008). Mack’s (Reference Mack2009) analysis of the normative structure and state forms of recognition through which Indigenous legal orders must be seen for negotiations to persist foreshadows the asymmetrical relations that were reported in many cases during the first years of implementation. Furthermore, Crown parties’ failure to uphold treaty obligations that impact the everyday lives of First Nations signatories demonstrated the lived impacts of this asymmetrical relationship, whereby Crown parties were unaffected—even unaware—of their legally binding commitments. Recommendations to improve relationships under modern treaty provided by research participants overwhelmingly include communicating throughout all levels of government what a modern treaty entails and the respective obligations of each party to the treaty—“communicating into the depths of bureaucracy that there is a new relationship” (Shii-shii-kwalahp [Angela Wesley], interview by Sloan Morgan, September 2015). Allocating resources and experienced personnel to implementation committees—representatives who will not assume an issue surrounding fish migration is due to “not fishing hard enough”—is also integral. Representatives able to grasp the impact of modern treaties on lived realities and understand the priorities and conditions that each Maa-nulth Nation is responding to was recommended by most Maa-nulth negotiators and Huu-ay-aht First Nations leaders as key to respectful new relationships

Recognizing that treaties are in fact new relationships, rather than severance agreements, was also a key recommendation from many participants. Modern treaties require First Nations to hold an election within six months of the effective date. For most Maa-nulth First Nations, those sitting at the treaty table also held seats in First Nations’ governments. Mandatory elections can result in institutional memory loss and, with no instruction manual accompanying the 320-page treaty, create the near impossible task of new leadership having to learn the treaty while implementing a new form of self-governance. While understanding that time is required for all parties to internally define and operationalize new relationships, Huu-ay-aht participants suggested that support be provided to First Nations as they transition into self-governance, rather than “divorcing”:

[Y]ou could call it a new relationship, but is it a new, better relationship? … It’s not rooted in as much problem solving and seeing that there’s a collective effort… Yes, it’s true that that doesn’t exist, or it’s not in a policy, or there’s no pot of money for that. But how are we going to make it happen? That’s the kind of thinking [that is] going to make a difference. Nobody is going to foresee all these things that are coming up with implementation. But in order to overcome them, you have to be willing to do something that doesn’t exist, that’s not been done before. (Trudy Warner, former Huu-ay-aht Communications Lead during negotiation and current Huu-ay-aht First Nations’ Executive Director, interview by Sloan Morgan, August 2015)

Framing reconciliation as something “achieved” under treaty, as suggested in the federal government’s 2009 Act that assented the Maa-nulth Treaty: “…Whereas the Maa-nulth First Nations, the Government of Canada and the Government of British Columbia have negotiated the Agreement to achieve this reconciliation and to establish a new relationship among them…” (Government of Canada 2009), fails to view new relationships as long-term, enduring efforts. Such a perspective may even entrench asymmetrical relations within modern treaties, thereby maintaining the state’s ability to, as Mack (Reference Mack2009) has earlier asserted in regard to the negotiation process, “decide what aspects of the claim to recognize” (63). Even with modern treaties’ ability to “achieve” reconciliation still being on trial, when viewed within the normative state structures in which they are negotiated, their constitutional binding and thereby each signatory party’s legal obligation to uphold these agreements is unquestionable.

Conclusion

There is no one way to define a new relationship, nor is there a handbook dictating how modern treaties should be implemented. Each final agreement is uniquely responsive to local conditions, negotiated by Indigenous, federal, and provincial parties to comprehensively outline obligations, including settlement of land, finances, and Indigenous self-governance. For Indigenous Nations who decide modern treaty is their path to Crown recognition and who redefine a new relationship, the agreements outline obligations that will impact all aspects of community decision-making and community members’ lives for generations.

This paper has explored a “new relationship” created under the Maa-nulth Treaty for Huu-ay-aht First Nations, provincial, and federal parties. Our analysis revealed that the way new relationships are enacted, how they are being learned, and how they are subject to the political will of those in positions of power would benefit from more effective whole-of-government approaches to new relationships, and to recognizing that modern treaties “are going to affect [treaty signatories’] lives.” These findings reveal that a fundamental shift is required for all signatories to take seriously the impact agreements have on the lives of First Nations that have collectively agreed to move forward under treaty, and to recognize the asymmetrical relationship that can remain in new relationships. While provincial and federal signatories have taken steps to ensure their responsibilities under treaty are operationalized, education within the bureaucracies of both are required to ensure new relationships are approached and implemented with respect.