Introduction

Parasitoids belonging to the family Encyrtidae (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) are important natural enemies used in the biological control of insects (Fallahzadeh and Japoshvilli Reference Fallahzadeh and Japoshvili2010). Currently, more than 4000 species of the family Encyrtidae are known throughout the world (Noyes Reference Noyes2019) and are composed by several genera, such as Blastothrix (Mayr), Diversinervus (Silvestri), Encyrtus (Latreille), Metaphycus (Mercet), Microterys (Thomson) (Kapranas and Tena Reference Kapranas and Tena2015), and Ooencyrtus (Ashmead), which are important population regulators of insect pests present in different agricultural and forest ecosystems (Corrêa-Ferreira and Moscardi Reference Corrêa-Ferreira and Moscardi1995; Peri et al. Reference Peri, Cusumano, Agro and Colazza2011; Mainali and Lim Reference Mainali and Lim2012; Tunca et al. Reference Tunca, Colombel, Venard and Tabone2017).

The genus Ooencyrtus comprises more than 300 known species worldwide (Noyes Reference Noyes2019). The species Ooencyrtus submetallicus (Howard) (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) is an endoparasitoid, which is reproduced by thelytoky parthenogenesis in the eggs of its hosts (Wilson and Woolcock Reference Wilson and Woolcock1960). Female diploid individuals are derived from unfertilised eggs (Stouthamer Reference Stouthamer1997; Espinosa et al. Reference Espinosa, Virla and Cuozzo2016), because they do not depend on mating (Monti et al. Reference Monti, Nugnes, Gualtieri, Gebiola and Bernardo2016).

The first record of O. submetallicus was in Granada, in the British West Indies, parasitising Nezara viridula (Linnaeus) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) eggs. Later it was imported from Australia (Wilson and Woolcock Reference Wilson and Woolcock1960). Then, this parasitoid was discovered in Puerto Rico in 1963, parasitising pupae of Hippelates pusio (Loew) (Diptera: Chloropidae) (Legner and Bay Reference Legner and Bay1965). In Brazil, this parasitoid has already been registered in eggs of N. viridula and Piezodorus guildinii (Westwood) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in the state of Paraná (Corrêa-Ferreira and Moscardi Reference Corrêa-Ferreira and Moscardi1995), in eggs of Pentatomidae predatory species (Zanuncio et al. Reference Zanuncio, Oliveira, Torres and Pratissoli2000), in eggs of Chinavia pengue (Rolston) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae), in eggs of Euschistus heros (Fabricius) (Godoy et al. Reference Godoy, Galli and Ávila2005; Ferreira Reference Ferreira2016; Eduardo et al. Reference Eduardo, Toscano, Tomquelski, Maruyama and Morando2018), and in eggs of the lepidopteran Erinnyis ello (Linnaeus) (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) (Silva Reference Silva2017).

The Neotropical brown stink bug, E. heros, is the main insect pest within the complex of phytophagous stink bugs that attack soybean, Glycine max Linnaeus (Fabaceae), in Brazil and Argentina, causing a marked reduction in the production of these crops due to their large population density (Silva et al. Reference Silva, Pasini, Bueno, Bortolotto, Barbosa and Cruz2014; Panizzi and Lucini Reference Panizzi and Lucini2016; Tuelher et al. Reference Tuelher, da Silva, Rodriques, Hirose, Guedes and Oliveira2018). For feeding, E. heros inserts its stylet into the soybean pods, the insect’s preferred food location, reaching the grains, which can cause severe damage to these grains or seeds produced (Depieri and Panizzi Reference Depieri and Panizzi2011; Silva et al. Reference Silva, Silva, Depieri and Panizzi2012).

Egg parasitoids are important agents for biological control of E. heros in soybean crop (Pacheco and Corrêa-Ferreira Reference Pacheco and Corrêa-Ferreira2000). In Brazil, 23 species of stink bug egg parasitoids, including Trissolcus basalis (Wollaston) (Corrêa-Ferreira and Moscardi Reference Corrêa-Ferreira and Moscardi1995), Trissolcus urichi (Crawford), and Telenomus podisi (Ashmead) (Hymenoptera: Platygastridae), have already been reported due to their high potential for parasitism in hosts (Bueno et al. Reference Bueno, Sosa-Gómez, Corrêa-Ferreira, Moscardi and Bueno2012). Studies with O. submetallicus as a population regulator of phytophagous stink bugs are still scarce; however, a study carried out in a semi-field condition proved its effectiveness in parasitising its hosts (Ferreira Reference Ferreira2016).

Host density is a determining factor for the quality of offspring (Pereira et al. Reference Pereira, Zanuncio, Pastori, Chichera, Andrade and Serrão2010). This fact is attributed to parasitoid wasps that have behavioural responses to the density of the host, which can lead to a high rate of parasitism, depending on density and the consequent efficient local regulation of stink bug populations (Laumann et al. Reference Laumann, Moraes, Pareja, Botelho, Maia, Leonardecz and Borges2008). The relationship between the number of parasitoids and hosts may vary according to the preference for the species, age, and time of exposure to the host (Faria et al. Reference Faria, Torres and Farias2000).

The objective of this work was to evaluate the reproduction of O. submetallicus females in different densities of E. heros eggs to discern the optimal parasitoid:host ratio for rearing under laboratory conditions.

Materials and methods

The experiment was carried out at the Laboratory of Biological Control of Insects at the Federal University of Grande Dourados, Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil.

Experimental stock

Ooencyrtus submetallicus adults were obtained from the Biological Control Laboratory of Insects and reared according to the methods described by Faca et al. (Reference Faca, Pereira, Fernandes, da Silva, Costa and Wengrat2021). The rearing was kept in a Biochemical Oxygen Demand air-conditioned chamber (ELETROLab®, model EL 222, São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil), at 25 ± 2 °C, 70 ± 10% relative humidity, and 12:12 light:dark hours. Taxonomic identification of the parasitoid species was conducted by specialist Dr. Valmir Antonio Costa, Instituto Biológico in Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil. Voucher specimens of the parasitoid are deposited in the Entomophage Insects Collection “Oscar Monte”, in the Biological Institute – Advanced Centre for Research in Plant Protection and Animal Health in Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil, under number IB-CBE-569-2.

An E. heros colony was established by individuals from collections in soybean crops (−22.409546° latitude, –54.496063° longitude), in the municipality of Fátima do Sul, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. The methodology described by Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Laumann, Blassioli, Pareja and Borges2008) was used to rear E. heros. The rearing cages (20 cm deep × 15 cm wide × 20 cm high) were kept in an air-conditioned chamber at 25 ± 2 °C, 70 ± 10% relative humidity, and 14:10 light:dark hours.

Experiment

Nonparasitised E. heros eggs that were 24 hours old were glued in sky-blue cartons (0.50 cm × 1.00 cm) with gum arabic (20% water). They were later inserted in glass tubes (1.00 cm diameter × 9.50 cm high) with food (drop of honey) and one O. submetallicus female that was five to six days old, which is when the eggs in the parasitoids’ ovaries reach appropriate level of maturity (Faca et al. Reference Faca, Pereira, Fernandes, da Silva, Costa and Wengrat2021), in densities of 1:3, 1:6, 1:9, 1:12, 1:15, or 1:18 (parasitoid:nonparasitised eggs). Parasitism was allowed for 24 hours. After this period, O. submetallicus females were removed, and the eggs remained in the glass tubes, which were kept in a climate-controlled chamber at 25 ± 2 °C, 70 ± 10% relative humidity, and 12:12 light-dark hours until the adult emergence of O. submetallicus.

Several biological characteristics were evaluated. The parasitism percentage was (number of dark eggs/total number of eggs) × 100, and the emergence percentage was (number of eggs with hole/number of dark eggs) × 100. The parasitised eggs were determined by identifying the colour change, because parasitised eggs have a colour that is darker than the natural yellowish colouration of nonparasitised eggs (Medeiros et al. Reference Medeiros, Schimidt, Loiácono, Carvalho and Borges1997). The number of individuals that emerged from each stink bug egg was counted by observing the number of adult parasitoids that emerged. The length of the parasitoid posterior tibia was used as a basis to correlate the body size of the adult parasitoid. As such, the length of the posterior tibia was measured from the joint with the femur to the junction with the tarsus for 10 randomly selected emerged females (Bai et al. Reference Bai, Luck, Foster, Stephens and Janssen1992; Olson and Andow Reference Olson and Andow1998), using a stereoscopic microscope (Discovery V8; ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany) and microscope software ZEN lite (ZEISS) to make morphometric measurements.

Life cycle was considered as the time required for development of the immature parasitoid, measured from the day of parasitism until the emergence of the adult parasitoid. Female longevity (adult parasitoid survival period), in days, was determined by randomly selecting 15 individuals from each treatment (different egg density), collected on the day of their emergence, and later individualised in an Eppendorf tube, fed with honey that was dispersed in droplets, where the female parasitoids remained until their death. Sex ratio [Σ♀/Σ(♀ +♂)] was also determined.

Statistical analysis

The experimental design used was completely randomised with six treatments (egg densities) and 12 repetitions for each treatment. Each repetition consisted of a glass tube with one female and one egg carton. The data were subjected to the Shapiro–Wilk normality test (Shapiro and Wilk Reference Shapiro and Wilk1965). Data on percentage of parasitism and emergence, number of parasitised eggs, number of individuals per egg, the length of the posterior tibia, and longevity were subjected to analysis of variance. The means were compared by the Tukey test (P ≤ 0.05), using the statistical software Assistat (Silva and Azevedo Reference Silva and Azevedo2016). The means of duration of the life cycle and sex ratio were not subjected to the statistical analysis.

Results

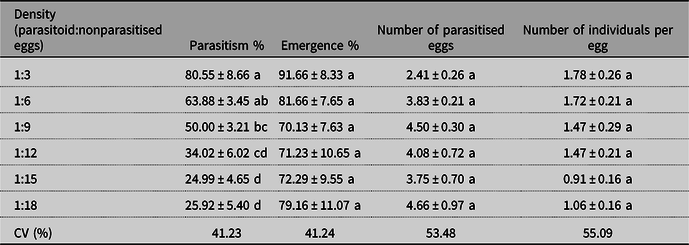

The percentage of parasitism was affected by the different densities of E. heros egg offered to the O. submetallicus females (F = 16.378, df = 5, P = 0.0001) (Table 1). The percentage of parasitoid emergence was not influenced by the different egg densities per female (F = 0.797, df = 5, P = 0.5552; Table 1). The number of E. heros eggs parasitised by an O. submetallicus female and the number of individuals that emerged from E. heros eggs were not differentiated by densities (F = 1.791, df = 5, P = 0.1268 and F = 1.250, df = 5, P = 0.2958, respectively; Table 1).

Table 1. Means (± standard error) of the parasitism (%), emergence (%), number of parasitised eggs, and number of individuals per eggs of Ooencyrtus submetallicus adults exposed to different egg densities of host Euschistus heros.

Note: Means (± standard error) followed by the same letter in the column do not differ statistically from each other by the Tukey test (P ≤ 0.05). CV, coefficient of variation.

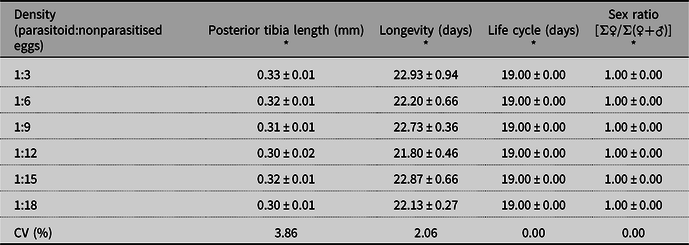

The posterior tibia length and longevity of the emerged adult parasitoids were not influenced by the different densities (F = 0.966, df = 5, P = 0.4463 and F = 0.595, df = 5, P = 0.7036, respectively; Table 2). The life cycle duration (egg to adult) and sex ratio were not influenced by the different E. heros egg densities (P > 0.05). In general, the averages obtained for life cycle duration (egg to adult) and sex ratio evaluated were 19.00 ± 00.00 days and 1.00 ± 00.00, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Means (± standard error) of the posterior tibia length, life cycle duration, longevity, and sex ratio of Ooencyrtus submetallicus adults exposed to different egg densities of host Euschistus heros.

* Analysis of variance (P > 0.05) is not significant. CV, coefficient of variation.

Discussion

The results of this study are fundamental for understanding the behavioural responses of O. submetallicus to the nonparasitised egg density of E. heros hosts that are subjected to 24 hours of parasitism. The ideal density for the mass multiplication of the parasitoid O. submetallicus was 1:6 (parasitoid:nonparasitised eggs), demonstrating a decreasing parasitism as the number of nonparasitised eggs increases.

The ideal density indicates that for the reproduction of this parasitoid, the 1:6 (parasitoid:nonparasitised eggs) ratio can provide the best biological performance. When the egg parasitoid Trissolcus is subjected to high nonparasitised egg densities of their host E. heros, they are able to parasitise to their limit, but after this a decrease in their parasitism rate occurs at high densities (Laumann et al. Reference Laumann, Moraes, Pareja, Botelho, Maia, Leonardecz and Borges2008).

Females of Trichogramma species that are presented to their host eggs take a certain period to recognise the hosts. After this, the ovipositor is inserted, and oviposition occurs (Moreira et al. Reference Moreira, dos Maria, Beserra, Torres and Almeida2009). Consequently, the 24-hour exposure of the parasitoid females to host eggs at higher densities may have been insufficient to define their parasitism potential (Polanczyk et al. Reference Polanczyk, Barbosa, Celestino, Pratissoli, Holtz and Milanez2011). In the present study, we obtained a percentage of emergence that was higher than 70% for all egg densities studied, indicating that E. heros eggs are appropriate for parasitoid O. submetallicus development. However, the dissection of E. heros eggs was necessary to verify that all adult parasitoids had emerged. The eggs are morphologically characterised by having a circular cover on the surface, known as an operculum, attached to stink bugs egg masses, which facilitates the emergence of parasitoids (Esselbaugh Reference Esselbaugh1946). The presence of adults was not observed inside eggs from which no emergence occurred.

Parasitoid efficiency in overcoming the host’s immune responses has been widely studied in the larval and pupal stages. However, the immune response within the egg remained unknown. Cusmano et al. (Reference Cusmano, Duvic, Jouan, Ravallec, Legeai and Peri2018) report that Ooencyrtus telenomicida (Vassiliev) (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) injects substances that are involved in the physiological modifications of their hosts to favour the development of their descendants in N. viridula eggs.

The number of parasitised eggs in the present study can be explained by parasitoid reproduction that is conducted in the same alternative host for several generations. This indicates a probable preimaginal conditioning of the parasitoid, which is the preference for the alternative host, that is acquired during parasitoid larval development (Cobert Reference Cobert1985) and may be directly linked to genetic inheritance and traits inherited across generations (Goulart et al. Reference Goulart, De Bortoli, Thuler, Pratissoli, Vianna and Volpe2008).

A greater number of individuals were obtained at lower densities in the present study due to the superparasitism by parasitoid females. Under laboratory conditions, low host density results in superparasitism, which is when a parasitoid female lays more than one egg in a single host (Godfray Reference Godfray1987; Rosenheim Reference Rosenheim1993). In the context of the present study, superparasitism by parasitoid species is of no interest for the parasitoid’s mass rearing, as it can result in intrinsic competitions between parasitoid larvae for a single host, leading to breeding implications (Kaser and Ode Reference Kaser and Ode2016) where there are more individuals per host and with lower body size due to reduced availability among the competing larvae of resources for their development during the larval phase (Pereira et al. Reference Pereira, Guedes, Serrão, Zanuncio and Guedes2017). Superparasitism observed between larvae of Trichogramma pretiosum (Riley) (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) resulted in competition for food by larvae that led to smaller and deformed individuals, when the parasitoids were exposed to different egg densities of Plutella xylostella (Linnaeus) (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) (Pereira et al. Reference Pereira, Barros and Pratissoli2004). Ooencyrtus kuvanae (Howard) (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) exposed to nonparasitised egg densities of Lymantria dispar (Linnaeus) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) exhibited increased development time, decreased life expectancy, and reduced body size (Tunca et al. Reference Tunca, Colombel, Venard and Tabone2017).

Understanding the reproductive biology of parasitoids is essential, because it is related to egg production and female fertility (Papaj Reference Papaj2000). Parasitoids can be classified as pro-ovigenic or synovigenic in relation to how they produce eggs. Synovigenic parasitoid females give rise to offspring that, upon reaching sexual maturation, have several immature eggs with the ability to produce new eggs throughout their adult life (Flanders Reference Flanders1950). In some species, the formation of gametes (oogenesis) is not complete at the time of emergence, as in Ooencyrtus spp. (Battisti et al. Reference Battisti, Ianne, Milani and Zanata1990). In this case, many females of synovigenic species need a greater amount of nutrients to sustain oogenesis (Tunca et al. Reference Tunca, Colombel, Ben Soussan, Buradino, Galio and Tabone2015). In fact, synovigenic sexual maturation is a characteristic present in the Encyrtidae family (Kapranas and Tena Reference Kapranas and Tena2015). Ooencyrtus submetallicus requires more time and nutritious resources to better exploit its host eggs when subjected to higher densities and thus parasitise their hosts. The genus Ooencyrtus has the ability to deposit more than one egg inside host eggs at the lowest densities and is not selective when they decide to parasitise or superparasitise their hosts (Tunca et al. Reference Tunca, Colombel, Venard and Tabone2017).

The length of the posterior tibia serves as a base parameter for the body size of adult parasitoids (Kazmer and Luck Reference Kazmer and Luck1991). In species of Trichogramma, the size of the body is determined by the species of the host in which the parasitoid individual developed and by its ability to exploit the nutritional resources and develop inside the host (Bai et al. Reference Bai, Luck, Foster, Stephens and Janssen1992; Greenberg et al. Reference Greenberg, Nordlund and Wu1998; Olson and Andow Reference Olson and Andow1998). The inadequate choice of host for the reproduction of this parasitoid results in parasitoids of inferior biological quality. Individuals with larger body size have greater capacity to find females and mate, are better able to locate their hosts, live longer, and have greater female fertility; they are, therefore, at a competitive advantage (Waage and Ng Reference Waage and Ng1984; Bai et al. Reference Bai, Luck, Foster, Stephens and Janssen1992; Godfray Reference Godfray1994).

The average life cycle (egg to adult) of E. heros is approximately 28.4 days at 25 °C (Panizzi et al. Reference Panizzi, Bueno and Silva2013), and the life cycle of O. submetallicus corresponds to 60% of E. heros life cycle; that is, the parasitoid reaches the adult stage faster than its host does (Ferreira Reference Ferreira2016). Therefore, the parasitoid life cycle, when reared in this host, does not undergo biological changes. Longevity consists of the survival period of an adult parasitoid until its death. This biological characteristic makes it possible to estimate the parasitoid survival during fieldwork and allows for better synchronisation in the establishment of biological control agents in cultures (Sorensen et al. Reference Sorensen, Addison and Terblanche2012). In this way, longevity helps to determine the number of inoculative releases needed to control insect pest populations in agricultural areas.

Energy expenditure during oviposition is related to parasitoid longevity (Pacheco and Corrêa-Ferreira Reference Pacheco and Corrêa-Ferreira1998). At the 1:3 density ratio (parasitoids:nonparasitised eggs), which in the present study was the treatment with a lowest number of host nonparasitised eggs, the female parasitoids expended more energy when they deposited more than one egg per host; however, this factor did not influence O. submetallicus longevity. In the present study, the parasitoids in each treatment were maintained under the same constant physiological conditions of food, photoperiod, relative humidity, and temperature; therefore, longevity was not affected by the density of eggs to which they were exposed. Oliveira et al. (Reference Oliveira, Silva, Oliveira, Andrade, Pereira and Zanuncio2018) found that the parasitoid Trichospilus diatraeae (Margabandhu and Cherian) (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) exhibited similar longevity between treatments when exposed to different pupae densities of Anticarsia gemmatalis (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae). When the objective is mass production, the ability of natural enemies to survive is a factor of interest in efficient management in the field (Queiroz et al. Reference Queiroz, Bueno, Pomari-Fernandes, Grande, Bortolotto and Silva2017).

The parasitoid sex ratio was not affected by E. heros egg densities. This is a determining factor when choosing a parasitoid species for successful implementation of biological control programmes, where greater production of females is desirable, because they are responsible for parasitism (Bueno et al. Reference Bueno, Parra, Bueno and Haddad2009). In addition, the number of females produced is essential to maintain and increase the population of natural enemies (Heimpel and Lundgren Reference Heimpel and Lundgren2000).

Houseweart et al.’s (Reference Houseweart, Jennings, Welty and Southard1983) hypothesis is that the reduced age-dependent number of female individuals of Trichogramma spp. is due to only enough sperm in the spermatheca to successfully copulate only once, thereby reducing egg fertilisation and the number of females. Ooencyrtus submetallicus reproduction occurs by thelytoky parthenogenesis, which generates female individuals. Males are rare in this species but can emerge in particular conditions, such as when the temperature reaches a critical 29.44 °C (Wilson and Woolcock Reference Wilson and Woolcock1960). Because of this reproductive method, copulation is rare within this species.

Based on the biological characteristics of O. submetallicus, the ideal density for reproduction in E. heros eggs under laboratory conditions can be recorded. The species parasitises Pentatomidae hosts, is a generalist parasitoid, and has interesting characteristics that have been observed in the laboratory. The present study establishes a basis for future work in the semi-field and field, because the parasitoid has the potential to be used in biological control programmes for E. heros.

Ooencyrtus submetallicus parasitised and developed in E. heros eggs in all evaluated densities, with 1:6 being the optimal combination of parasitoids and hosts in the 24-hour period of parasitism.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Brazilian agencies Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – CAPES and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq (Process no. 304 055/2019-0) for granting a scholarship to the first author. They are also grateful to Dr. Jocelia Grazia for the taxonomic identification of Euschistus heros and to Dr. Valmir Antonio Costa for the taxonomic identification of Ooencyrtus submetallicus.