Like other Diptera, the life cycle of Piophilidae is composed of six main stages: egg, three larval instars, “pupal” stage (which includes the entire intra-puparial period, from pupariation to adult emergence, i.e., prepupal, pupal, and pharate adult stage), and adult (Martín-Vega et al. Reference Martín-Vega, Hall and Simonsen2016). The adults are small brachycerous flies measuring 3–6 mm (McAlpine Reference McAlpine1987). They vary in colour from shining black or blue to dull brown or yellow (McAlpine Reference McAlpine1987; Byrd and Tomberlin Reference Byrd, Tomberlin, Byrd and Tomberlin2020). Piophilidae can be distinguished from similar small fly families by their divergent postocellars (convergent in Heleomyzidae), the absence of strong spines along the costal vein of the wings (present in Heleomyzidae), and the presence of both vibrassa on cheeks and a subcostal break on the costal vein of the wings (both criteria absent in Sepsidae) (Rochefort et al. Reference Rochefort, Giroux, Savage and Wheeler2015). The family contains 23 genera and 82 families, of which 37 are found in the Nearctic area (McAlpine Reference McAlpine1987; Bickel et al. Reference Bickel, Pape, Meier, Bickel, Pape and Meier2009). Larvae are cylindrical, white, legless, and elongated, measuring 5–10 mm (McAlpine Reference McAlpine1987; Byrd and Tomberlin Reference Byrd, Tomberlin, Byrd and Tomberlin2020). The eggs, with chorion partially transparent and white, measure 0.7 mm × 0.2 mm (e.g., Piophila casei; Mote Reference Mote1914).

Skipper flies are associated with various habitats. Both adults and larvae can be found on human waste, organic decaying matter, excrement, carrion (especially bones and skin), and fur (McAlpine Reference McAlpine1987; Byrd and Tomberlin Reference Byrd, Tomberlin, Byrd and Tomberlin2020). Notably, adults are known to breed in protein-rich plants or animal matter (McAlpine Reference McAlpine1987). Skipper fly larvae are also associated with food products such as cheese, smoked fish, or meat and are considered as major pests in the food industry (Byrd and Tomberlin Reference Byrd, Tomberlin, Byrd and Tomberlin2020). They can be responsible for intestinal myiasis when an infested product is ingested (Wyss and Cherix Reference Wyss and Cherix2013). Some species of skipper flies are also found on cadavers, and larvae of these species are mainly scavengers. Skipper fly larvae are known for their jumping behaviour in response to sound and moisture (Bonduriansky Reference Bonduriansky2002), which can be used for escaping or migrating (McAlpine Reference McAlpine1987; Byrd and Tomberlin Reference Byrd, Tomberlin, Byrd and Tomberlin2020).

Very little is known about the biology and development of skipper flies, and the existing studies often focus on Piophila casei Linnaeus, one of the most common species in the field of forensic entomology and in the food industry. An early study of this species reported durations of 23–54 hours for the egg stage, 14 days for the larval stage, and 12 days for the pupal stage but lacked further precision about the associated temperature (Mote Reference Mote1914). In related studies, it has been shown that the duration of P. casei’s development time decreased with temperature. Its mean total development time (egg to adult) varied from 57.1 days at 15 °C to 14.7 days at 32 °C, and the mean larval development time varied from 39.7 days at 15 °C to 10.6 days at 32 °C (Russo et al. Reference Russo, Cocuzza, Vasta, Simola and Virone2006). In contrast, adult longevity was shown to be negatively impacted by temperature, with the mean longevity of females varying from 20.5 days at 15 °C to 6.6 days at 32 °C and the mean longevity of males varying from 17.7 days at 15 °C to 6.5 days at 32 °C (Russo et al. Reference Russo, Cocuzza, Vasta, Simola and Virone2006). In another study performed on Prochyliza brevicornis (Melander, 1924), the average time of development (egg to adult) varied from 42 to 47 days at 26 °C (Syed Reference Syed1994). However, almost no information is available on the overwintering behaviour of skipper flies, especially in cold climates such as that of Québec, Canada.

In cold climates, insects, which are poikilothermic animals, have developed specific physiological adaptations or specific behaviours to survive winter. For example, some species choose to escape cold temperatures by migrating to warmer regions (e.g., monarch butterfly; Solensky Reference Solensky2004), whereas others, such as Mecoptera and Diptera: Tipulidae or Heleomyzidae, can remain active in snow (Sömme and Östbye Reference Sömme and Östbye1969; Soszynska-Maj and Woznica Reference Soszynska-Maj and Woznica2016). Finally, others – which represent the majority of insects in Québec – enter into diapause to overwinter. Diapause is an adaptive and genetically programmed phenomenon in response to an unfavourable environment or conditions (e.g., temperature, photoperiod, lack of food, or drought), which is characterised by a behavioural inactivity, the arrest of the functions of reproduction and morphogenesis, and reduced growth and metabolic activity (Hodek Reference Hodek2002; Tougeron Reference Tougeron2019). Diapause can be facultative or obligatory and involves different growth stages. Regarding insects of forensic interest, Silphidae and other Coleoptera are known mainly to overwinter at the adult stage (Ratcliffe Reference Ratcliffe1972; Byrd and Tomberlin Reference Byrd, Tomberlin, Byrd and Tomberlin2020), whereas Diptera overwinter at the larval, pupal, or adult stage, depending on the family and species (Vinogradova Reference Vinogradova1986).

Because some skipper fly species can be found on cadavers, they are important in the field of forensic entomology. The study of the succession of arthropods on a cadaver provides relevant information about the time elapsed since death, also called the post-mortem interval (Martín-Vega Reference Martín-Vega2011; Wyss and Cherix Reference Wyss and Cherix2013; Huntington et al. Reference Huntington, Weidner and Hall2020). According to Mégnin (Reference Mégnin1894), eight “squads” of arthropods colonise a cadaver through time, depending on the decomposition stages and post-mortem period. Skipper flies were reported to be part of the fourth wave of arthropods that colonise a cadaver, arriving during caseic fermentation, which represents the fermentation of proteins (Wyss and Cherix Reference Wyss and Cherix2013). In studies performed on pig carcasses, skipper fly larvae are mainly associated with active decay, which is characterised by the liquefaction of the body, and with strong odours of decay (Payne Reference Payne1965). Adults can also be observed on cadavers earlier in the decomposition process – as soon as three or four days after death (Wyss and Cherix Reference Wyss and Cherix2013; Byrd and Tomberlin Reference Byrd, Tomberlin, Byrd and Tomberlin2020).

The purpose of this study was to investigate the overwintering behaviour of the skipper flies found on animal carcasses during fall in Québec, Canada. An experiment performed on pig carcasses during the summer of 2019 in Trois-Rivières, Québec showed that adults of the skipper fly were first recorded on the carcasses as soon as Day 0 – that is, the same day the carcasses were deposited at the experimental sites (fresh stage), which is in accordance with the literature, whereas larvae were first observed on the carcasses at the end of the advanced decay stage (Day 23) – that is, when flesh was removed at the extremities and when desiccation of tissues had occurred (Maisonhaute and Forbes Reference Maisonhaute and Forbes2020). Both adults and larvae were subsequently observed on the carcasses until the dry remains stage (starting from Day 34), which is characterised by the loss of soft tissue, with only dry skin, bones, hair, and teeth remaining on the carcasses (Payne Reference Payne1965).

Thirteen skipper fly species of forensic importance have been reported in the Nearctic region. Of these, seven have been reported in Canadian studies (Rochefort et al. Reference Rochefort, Giroux, Savage and Wheeler2015). These are Boreopiophila tomentosa Frey, 1930 (Gill Reference Gill2005), Liopiophila varipes Meigen, 1830 (Michaud et al. Reference Michaud, Majka, Privé and Moreau2010), P. casei (Sharanowski et al. Reference Sharanowski, Walker and Anderson2008), P. brevicornis (Anderson and Vanlaerhoven Reference Anderson and Vanlaerhoven1996), Prochyliza xanthostoma Walker, 1849 (Gill Reference Gill2005), Protopiophila latipes (Meigen, 1838) (Michaud et al. Reference Michaud, Majka, Privé and Moreau2010), and Stearibia nigriceps Meigen, 1826 (Anderson and Vanlaerhoven Reference Anderson and Vanlaerhoven1996; Gill Reference Gill2005; Michaud et al. Reference Michaud, Majka, Privé and Moreau2010). In addition to these species, Parapiophila spp. were also reported in New Brunswick, Canada (Michaud et al. Reference Michaud, Majka, Privé and Moreau2010). In Québec, specimens collected on pig carcasses in 2019 belonged to S. nigriceps, P. latipes, and Mycetaulus bipunctatus (Fallén, 1823) (Maisonhaute and Forbes Reference Maisonhaute and Forbes2020). This adds M. bipunctatus to the species recorded in Canada. Interestingly, adults of this species were observed on the carcasses during the dry remains stage only, whereas S. nigriceps and P. latipes (adults and larvae) were observed earlier in the decomposition process. Identifications were performed using Rochefort et al. (Reference Rochefort, Giroux, Savage and Wheeler2015) and were confirmed by the Laboratoire d’expertise et de diagnostic en phytoprotection (Ministère de l’Agriculture, des Pêcheries, et de l’Alimentation du Québec, Québec, Québec, Canada).

During summer 2019, skipper fly larvae collected from pig carcasses were successfully reared at the entomological laboratory of the Canada 150 Research Chair in Forensic Thanatology at the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Trois-Rivières, Québec. Mason jars of 500-mL or 1-L capacity, half filled with moist wood chips and covered with muslin tissue, were used as rearing containers, in which the wood chips represented a support for pupation. Larvae were deposited on a piece of pig liver and a piece of cheddar cheese in a small aluminium cup that was placed on the wood chips. The jars were placed in a growth chamber (Thermo Scientific Precision Model 818 Incubator, model PR505755L; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Marietta, Ohio, United States of America) at a temperature of 23.5 °C and a photoperiod 8:16 (dark:light), and plastic containers filled with water maintained sufficient humidity levels (30–70%) inside the chamber. Most of the adults that emerged were S. nigriceps, but a few specimens of P. latipes were also observed. At the end of the summer and during the fall, the number of adults emerging in the jars decreased drastically. It was noticed that most of the larvae were still alive, but few of them initiated pupation. For example, some larvae collected in mid-August remained in the larval stage for three months without initiating pupation.

A laboratory experiment was then performed to investigate this phenomenon and to determine whether the skipper fly larvae needed cold temperatures to complete their life cycle – that is, whether they experienced obligatory winter diapause. To simulate winter conditions, the skipper fly larvae (inside their original Mason jars or in the aluminium cup transferred into smaller plastic containers filled with wood chips and covered by muslin net) were stored inside the refrigerator at a constant temperature of 6 °C. Humidity inside the refrigerator was maintained at approximately 60%. A first batch of larvae (five replicates) was refrigerated on 25 October 2019 in order to verify whether the larvae could survive in these conditions. The remaining larvae and pupae were refrigerated on 20 November 2019 (31 replicates) and on 25 November 2019 (seven replicates), making for a total of 43 replicates (Table 1). Replicates contained larvae and some pupae collected from 8 August 2019 to 25 October 2019. Twenty-seven replicates contained both larvae and pupae, five replicates contained pupae only, and 11 replicates contained larvae only. Only eggs or larvae had been collected in the field, so any pupae present were the result of larvae that had transformed in the laboratory. Replicates were stored in the refrigerator for 84, 89, or 115 days (Table 1).

Table 1. Details of the overwintering experiment. Larvae of Piophilidae were collected on pig carcasses that reached the dry remains stage. Larvae and pupae (puparia) were stored in the refrigerator (at approximately 6 °C) during the winter, for 84–115 days. The mean and minimal ambient temperatures represent the average of the daily temperature recorded with the three data loggers installed on the pig’s cages. All replicates were removed from the refrigerator on 17 February 2020. E: eggs; L: larvae; P: pupae (puparia).

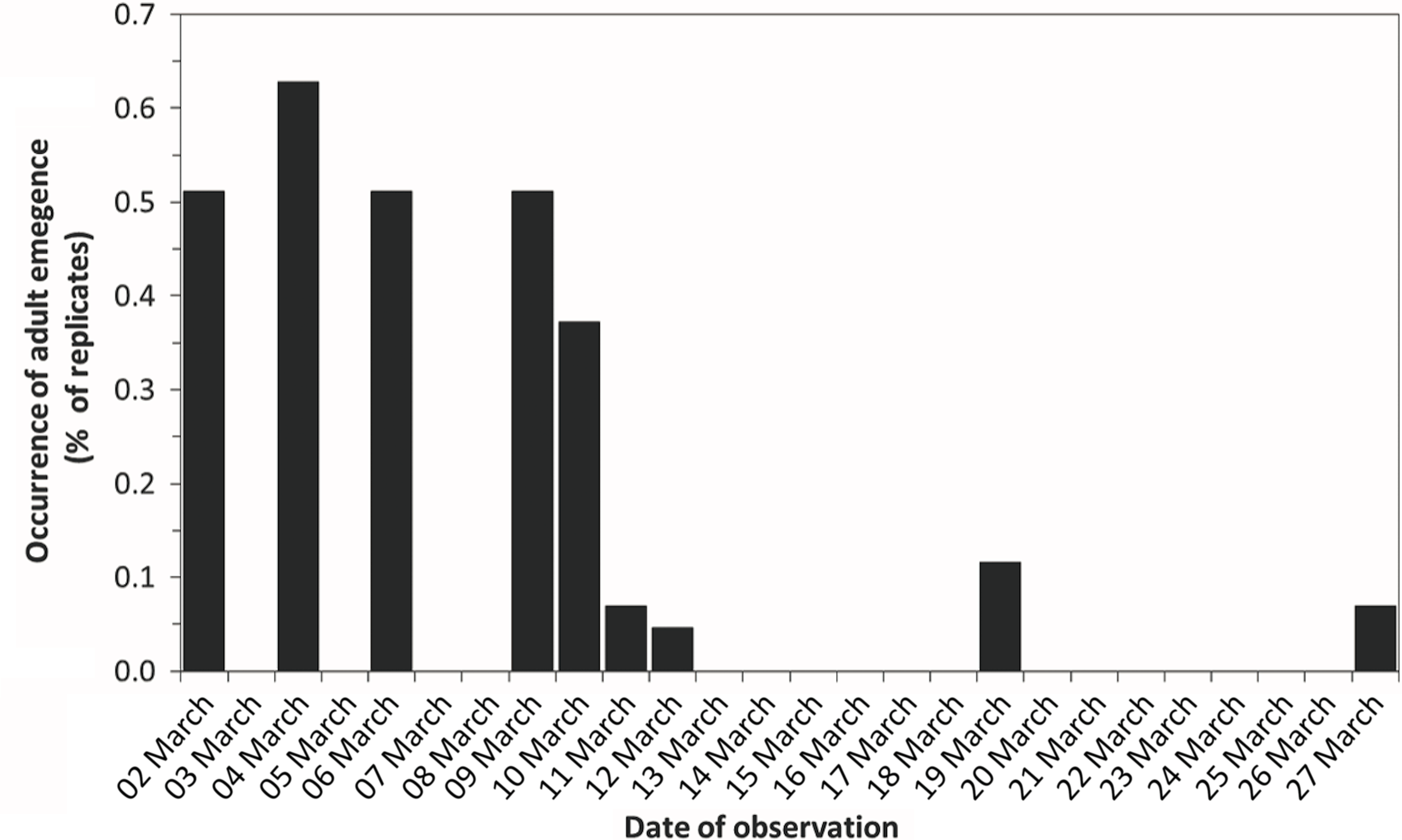

Larvae of all replicates were removed from the refrigerator on 17 February 2020 and placed again in the growth chamber, where they were reared according to the protocol that was followed during the summer (23.5 °C, 30–70% humidity). The larvae rapidly initiated pupation, which means that the cold temperatures imposed within the refrigerator from October or November to February allowed the larvae to complete their development. On 24 February, puparia or pupae were observed in all but two replicates that contained larvae (92.3%). Adult emergence was observed in 51.2% of the replicates on 2 March, 14 days after the removal from the refrigerator (Fig. 1), reached 62.8 % on 4 March, then decreased to 51.1% on 6 and 9 March and to 37.2% on 10 March, and was observed for up to six to seven weeks after placement in the growth chamber (27 March to early April, 7.0% of replicates). Adults emerged in 86% of the replicates (37 of 43 Mason jars). Half of the replicates with no adult emergence contained pupae only (three replicates), while only one replicate that contained larvae failed to produce adults (Table 1). Overall, our experiment showed that skipper fly larvae (and pupae) can survive cold temperatures (6 °C) for several months. Diapausing larvae of other Diptera species of forensic importance, such as Lucilia sericata (Meigen, 1826) (Calliphoridae), have also been found to survive cold temperatures (7 °C) for several months (Ichikawa et al. Reference Ichikawa, Ikeda and Goto2020).

Fig. 1. Occurrence of adult emergence (2020) in Piophilidae after exposure to cold temperatures during winter 2019/2020. Samples were placed in the refrigerator on 25 October, 20 November, and 25 November 2019 and were removed on 17 February 2020.

The observations made in the laboratory of very few adults emerging at the end of summer and fall, in addition to our laboratory experiment with a period of cold temperature over several months, demonstrate that the skipper fly larvae (S. nigriceps) collected during late summer and fall engaged in an obligatory winter diapause, as Syed (Reference Syed1994) suggested regarding another species, P. brevicornis. This means that skipper fly larvae can remain inside dead bodies for long periods in cold climates, and this makes estimating post-mortem interval difficult when the estimates are based on skipper fly larvae’s presence.

At the present time, no information on the minimum temperature required for the development and activity of Piophilidae is available. In our outdoor experiment, temperatures below 10 °C were observed from 10 September (minimal ambient temperature), and temperatures below 5 °C were observed from 10 October, whereas the minimum ambient temperature was 15 °C during August. The slowed development of the Piophilidae larvae and the commencement of the winter diapause could then be associated with this decrease in ambient temperature. Other observations made about several Diptera species of forensic importance indicate that temperature and photoperiod both have an effect on inducing diapause, which occurs at the larval stage in Calliphoridae (e.g., Numata and Shiga Reference Numata and Shiga1995; Tachibana and Numata Reference Tachibana and Numata2004; Vinogradova and Reznik Reference Vinogradova and Reznik2013) and at the pupal stage in Sarcophagidae (Denlinger Reference Denlinger1972). More laboratory experiments with controlled temperature and photoperiod conditions are needed to determine at what temperature winter diapause in Piophilidae is induced.

Few decomposition studies have been conducted for a period longer than one year, which limits the data available on the overwintering behaviour of the different arthropod species associated with carrion. In our outdoor study that was initiated in June 2019, larvae of Piophilidae remained active inside the carcasses during the fall, but some of them were observed migrating deep into the soil to overwinter (Pecsi, personal communication). Observations of the carcasses were performed until the day before the first snowfall (6 November 2019) and, despite the low temperatures recorded (mean temperature: 1.2 °C; minimum temperature: −1.9; maximum temperature: 4.2 °C; Government of Canada 2019), skipper fly larvae remained present inside the carcasses. The pigs’ thick skin, which had desiccated due to the decomposition process during summer, seemed to have protected the larvae from the cold. In spring 2020 (starting in April), when the snow thawed and the carcasses became accessible again, field observations confirmed the presence and activity of skipper fly larvae inside the carcasses, supporting the hypothesis of an obligatory winter diapause occurring at the larval stage, notably at lower temperatures than those recorded in our laboratory study. Similar observations were reported in Poland, where Piophilidae larvae (S. nigriceps) were found overwintering in pig carcasses (Mądra et al. Reference Mądra, Frątczak, Grzywacz and Matuszewski2015).

In conclusion, field observations confirmed that skipper fly species associated with carrion, especially S. nigriceps, overwinter in the larval stage in Québec, Canada, can remain inside a carcass throughout winter and can initiate pupation the following spring. In addition, laboratory experiments suggest the species undergo an obligatory diapause that is associated with cold temperatures. It is advised that forensic entomology investigations take this information into account when estimating the minimum time elapsed since death for bodies that are recovered in the spring and that may have been deposited weeks or months previously.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Fonds de Recherche du Québec (AUDACE programme, Frank Crispino, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières) and the Canada 150 Research Chair in Forensic Thanatology (C150-2017-12) for funding this project, the Laboratoire d’expertise et de diagnostic en phytoprotection, Ministère de l’Agriculture, des Pêcheries, et de l’Alimentation du Québec for fly identifications, Sophie Morel and Anne-Marie Marchand (BSc., Ecological and Biological Sciences, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières) for help in field sampling and lab work, and the team of the Canada 150 Research Chair in Forensic Thanatology that assisted with the project (Darshil Patel, Rushali Dargan, Emily Pecsi, Karelle Seguin, and Ariane Durand-Guevin).