Introduction

With more than 25 000 described species, orchids (Orchidaceae) represent a plentiful resource for herbivorous insects, either as food, larval host, or both (Swezey Reference Swezey1945; Rivera-Coto and Corrales-Moreira Reference Rivera-Coto and Corrales-Moreira2007). Weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in particular use this resource extensively. Associations with orchids have been documented for species of the weevil subfamilies Baridinae, Brachycerinae, Conoderinae, Cossoninae, Cyclominae, Dryophthorinae, Entiminae, Molytinae, and Scolytinae (Weiss Reference Weiss1917; Swezey Reference Swezey1945; Voss Reference Voss1961; Morimoto Reference Morimoto1994). When introduced to other regions, these beetles may pose a risk to native orchid populations and their habitats if they become established. Even though Voss (Reference Voss1961) considered this a rather unlikely scenario in temperate regions, some natural hosts of northern orchid weevils are holarctic and inadvertent dispersal and establishment of orchid weevils across temperate biogeographic realms seems only a matter of time.

The present study is concerned with the native North American orchid weevils found in Canada. All three species belong to the subfamily Baridinae in the sense of Bouchard et al. (Reference Bouchard, Bousquet, Davies, Alonso-Zarazaga, Lawrence and Lyal2011), or to the respective subordinate rank (supertribe or tribe) of Conoderinae in more recent classifications (Prena et al. Reference Prena, Colonnelli and Hespenheide2014; Pullen et al. Reference Pullen, Jennings and Oberprieler2014). They represent the most northern populations of orchid weevils anywhere in the world. Two of them attracted repeatedly the attention of botanists and ecologists during their studies of North American orchids, with Stethobaris ovata (LeConte, Reference LeConte1869) so far having caused the greatest concern in Canada (Brown Reference Brown1966; Reddoch and Reddoch Reference Reddoch and Reddoch1997, Reference Reddoch and Reddoch2009; Light and MacConaill Reference Light and MacConaill2011). Not treated herein (but included in the key) are two unestablished exotic species of the same subfamily, which have been found sporadically on imported orchid cultivars in British Columbia, Nova Scotia, and Ontario, Canada before 1990 (McNamara Reference McNamara1991; Majka et al. Reference Majka, Anderson and McCorquodale2007b; Prena Reference Prena2008). The first, Orchidophilus aterrimus (Waterhouse, 1874), is native to the Indo-Pacific region and has been dispersed widely with traded orchids (Prena Reference Prena2008). The other, Stethobaris laevimargo (Champion Reference Champion1916), a Neotropical species with uncertain provenance, appeared for the first time around 1915 in New Jersey and New York, United States of America (Champion Reference Champion1916; Weiss Reference Weiss1917) and afterward at many other places in North America including Ontario.

Material and methods

Weevil specimens were studied from the following collections and the acronyms are used to refer to them in the text: American Museum of Natural History, New York, New York, United States of America (AMNH); Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (CMNC); Canadian National Collection of Insects, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (CNCI); Pierre de Tonnacour personal collection, Terrasse-Vaudreuil, Québec, Canada (CPTO); Charles W. and Lois O’Brien personal collection, Green Valley, Arizona, United States of America (CWOB); Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America (MCZ); Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources, Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia, Canada (NSNR); Reginald P. Webster personal collection, Charters Settlement, New Brunswick, Canada (RPWC); Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, United States of America (TAMU); University College of Cape Breton, Sydney, Nova Scotia, Canada (UCCB); and Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington, District of Columbia, United States of America (USNM). The data pertaining to NSNR, RPWC, and UCCB are verified records (Majka et al. Reference Majka, Anderson, McAlpine and Webster2007a, Reference Majka, Anderson and McCorquodale2007b) for specimens not studied by myself. Collecting records are arranged by provinces, from west to east, and alphabetically within provinces. Additional state records from the United States of America are given without details (all data in my database, available on request) using the same regions as in O’Brien and Wibmer (Reference O’Brien and Wibmer1982).

Measurements of length were taken with a micrometer grid to the nearest tenth of a mm. Total length was measured from the elytral apex to the anterior margin of eye, and standard length to the anterior margin of pronotum.

Names of orchid species taken from the literature and labels were adjusted to modern names (National Plant Data Team 2016). For example, all associations reported for Habenaria Willdenow apply to species of Platanthera Richard. The record of “Habenaria hyperborea” by S.D. Hicks (Brown Reference Brown1966) is interpreted as Platanthera aquilonis Sheviak. Unpublished data used herein for tallies of host associations are available on request.

Stethobaris LeConte, 1876

Stethobaris LeConte, 1876: 302. Type species Baridius ovatus LeConte, Reference LeConte1869, by subsequent designation (Brown Reference Brown1966) under erroneous assumption of monotypy (two nominal species plus one subjective synonym originally were included on pages 303 and 420, making the synonym eligible for designation).

Diorymerellus Champion, Reference Champion1908: 252. Type species Diorymerellus laevipennis Champion, Reference Champion1908, by original designation. Synonymy with Stethobaris by Brown (Reference Brown1966).

Diagnosis. Species of Stethobaris are small (2–4 mm, rarely up to 6 mm), glabrous, rather shapelessly ovate, black to red weevils without metallic sheen. Their recognition has been, and to a considerable degree still is, obscured by the great diversity of ovate New World barids with similarly depauperate suites of morphological characters. Males of probably all tropical species of Stethobaris in the widest sense have up to three elytral interstriae with distinct subapical sulci (see fig. 5 in Prena and O’Brien Reference Prena and O’Brien2011). However, the species of both temperate hemispheres of the New World have a mere, usually inconspicuous, single streak of enlarged interstrial pits whereas the type species lacks this apomorphy altogether. Other morphological characters of diagnostic value include a conspicuous, subtriangular prosternal impression with two anterior pits; relatively large antennal club; and small, basally separate claws. The entire suite of characters applies to ~45 described species currently placed in Stethobaris LeConte, 1876 (including Diorymerellus Champion, Reference Champion1908); Cerpheres Champion, Reference Champion1908; Lasiobaris Champion, 1909 (with pilose surface); Montella Bondar, 1948; Ovanius Casey, 1922; and Prodinus Casey, 1922. Prena and O’Brien (Reference Prena and O’Brien2011) referred to this complex as Stethobaris sensu lato, with Stethobaris sensu stricto including the northern species with poorly developed or missing male interstrial sulci (the plesiomorphic condition). A similar and possibly related genus of orchid weevils occurs in eastern Asia. I have seen approximately six reddish-brown species of Phrissoderes Marshall, 1948, all with a similar depression on the prosternum as Stethobaris but with unmodified male interstriae and long, widely divergent claws. This is also one of the few presently known baridine genera outside the New World that have species with prosternal spines. Like in Stethobaris, most species of Phrissoderes are tropical, but at least P. rufitarsis (Roelofs, 1875) has a Palaearctic range (Prena Reference Prena2011).

Distribution and diversity. In broad terms, species of Stethobaris occur with distinctly more than 100 species in the New World from Canada down to at least Buenos Aires (Argentina) and Montevideo (Uruguay) as well as in the Greater and Lesser Antilles. The present-day distribution in Canada shows a conspicuous gap that corresponds closely with the extent of the Laurentide Ice Sheet around 10 000 BC (Dyke Reference Dyke2004). Numerous species have been and still are being dispersed outside their natural realm with traded ornamental plants. One amaryllid-associated species with uncertain origin became established in Barbados and the southeastern United States of America (Prena and O’Brien Reference Prena and O’Brien2011). North America north of Mexico has two or three introduced and seven native species, of which Stethobaris egregia Casey, Reference Casey1892 is essentially Central American and reaches southern Arizona and Texas, United States of America. However, the centre of diversity is in the Neotropics, from where only a very small fraction of the occurring species has been described.

Natural history. Although species of Stethobaris sensu lato are widespread in the New World and cause much concern among orchid growers, relatively little is known about their natural history. The best-studied species, S. ovata, has been reported from five orchid genera in three subfamilies (details in taxonomic section below). Howden (Reference Howden1995) found the female to be adaptable to the properties of the available hosts, with an oviposition behaviour that would change from host to host. Females deposited on nearly any part of the local orchid species in Ottawa, Ontario but appeared to prefer tender tissue. In a longer-term field study conducted in Québec, Light and MacConaill (Reference Light and MacConaill2011) determined a mean of 24% infested fruit capsules on Cypripedium parviflorum var. pubescens (Willdenow) Knight, with two out of 10 years showing values above 50%. Another study with comprehensive life history data is that by Epsky et al. (Reference Epsky, Weissling, Walker, Meerow and Heath2008) on the impact of Stethobaris nemesis Prena and O’Brien (Reference Prena and O’Brien2011) on Hippeastrum Herbert (Amaryllidaceae) hybrids. The weevils fed on and the larvae developed in the thickened leaf base but the authors did not explore whether orchids could be suitable alternative hosts. Prena and O’Brien (Reference Prena and O’Brien2011) mentioned that 48 species of Stethobaris sensu lato had been found on Orchidaceae and six on Amaryllidaceae. My unpublished records include associations with 33 orchid genera (Epidendroideae 25, Orchidoideae 5, Cypripedioideae 2, Vanilloideae 1) and five amaryllid genera but this tally is by no means representative of the actual host range.

Species native to Canada

Stethobaris ovata (LeConte)

Baridius ovatus LeConte, Reference LeConte1869: 363. Transferred to Stethobaris by LeConte (LeConte and Horn Reference LeConte and Horn1876).

Stethobaris congermana Casey, Reference Casey1892: 657. Synonymised with S. ovata by Blatchley and Leng (Reference Blatchley1916). Resurrected by Casey (Reference Casey1920). Reestablished synonymy.

Stethobaris convergens Casey, Reference Casey1920: 506. New synonym.

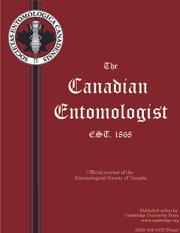

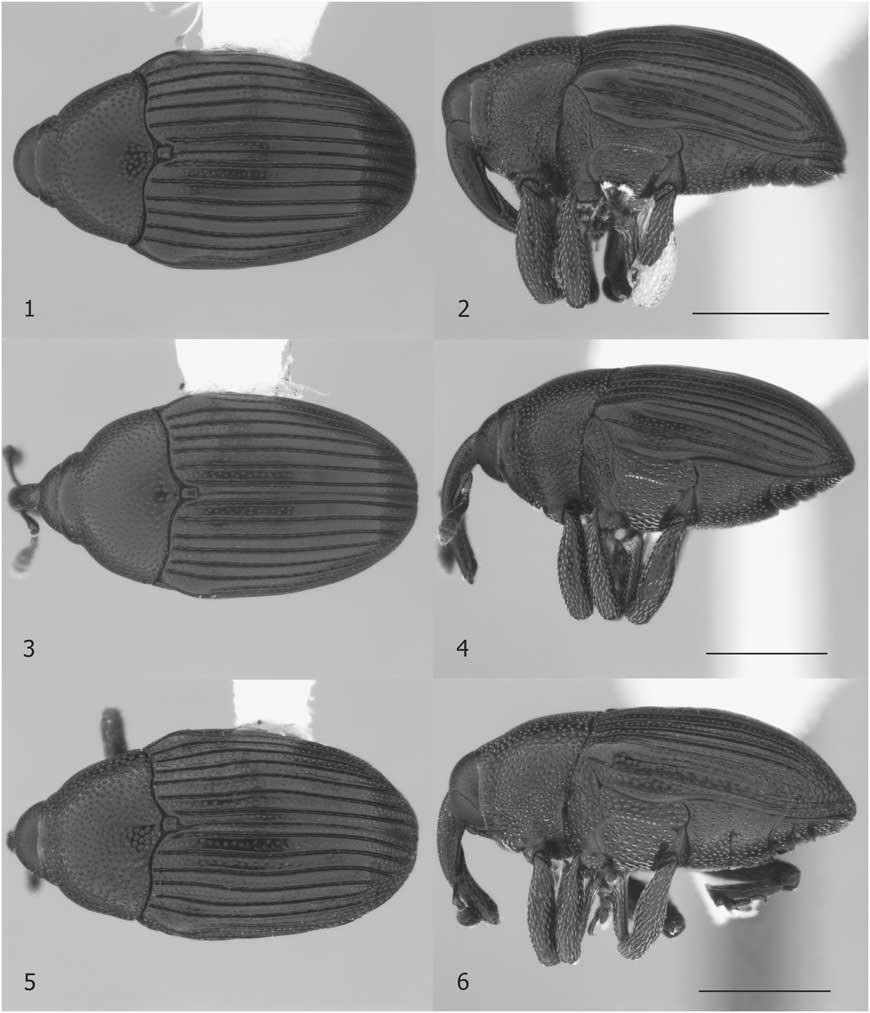

Diagnosis. Stethobaris ovata has a more strongly arched elytral disc than the other two native species (Fig. 2). The ovate penis with conspicuous denticles on the internal sac (Fig. 7) is highly diagnostic.

Distribution. Stethobaris ovata occurs in eastern Canada south of the Saint Lawrence River and along the northern shores of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, Québec). The western range continuous in the United States of America south of the Great Lakes at least to Wisconsin and connects to an old Canadian record from Manitoba. In the United States of America, the species occurs in the northeast (Connecticut, District of Columbia, Indiana, Massachusetts, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Wisconsin), southeast (Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia), southwest (Oklahoma, Texas), and central-north (Kansas, Missouri).

Natural history. Adult S. ovata have been found on Cypripedioideae (Cypripedium acaule Aiton, Cypripedium arietinum Brown, Cypripedium candidum Muhlenberg ex Willdenow, and Cypripedium parviflorum var. pubescens), Epidendroideae (Corallorhiza striata Lindley, Corallorhiza trifida Châtel, Epipactis helleborine (Linnaeus) Crantz), and Orchidoideae (Amerorchis rotundifolia (Banks ex Pursh) Hultén, Galearis spectabilis (Linnaeus) Rafinesque, Platanthera aquilonis, P. leucophaea (Nuttall) Lindley, P. psycodes (Linnaeus) Gray, Spiranthes casei Catling and Cruise) (Harrington Reference Harrington1884; Brown Reference Brown1966; Judd Reference Judd1979; Howden Reference Howden1995; Reddoch and Reddoch Reference Reddoch and Reddoch1997, Reference Reddoch and Reddoch2009; Dunford et al. Reference Dunford, Young and Krauth2006; Light and MacConaill Reference Light and MacConaill2011; Prena and O’Brien Reference Prena and O’Brien2011; Walsh et al. Reference Walsh, Arnold and Michaels2014). Along with Orchidophilus aterrimus and O. epidendri (Murray, 1869), S. ovata is one of the few orchid weevils known to develop in Cypripedioideae, or lady’s slipper orchids, whereas Epidendroideae and, to a lesser degree, Orchidoideae attract many weevil predators (J.P., unpublished data). Howden (Reference Howden1995) documented the oviposition behaviour at one site in Ottawa, Ontario. Single eggs were laid in May/June primarily in the stems of Corallorhiza trifida and, following the demise of this orchid species, primarily in the flowers of Epipactis helleborine. She concluded from her observations that the females changed their oviposition strategy because of the harder and tougher stem of E. helleborine. Light and MacConaill (Reference Light and MacConaill2011) found 2–59% of the Cypripedium parviflorum fruit capsules to be infested by S. ovata during a 10-year study in Parc de la Gatineau, Québec, with an average infestation rate of 24% in a total of 3293 examined capsules on 391 plants. The same authors observed that adult weevils started feeding upon buds and flowers of E. helleborine in late June to early July and oviposited in stems and developing fruits. Nothing is known about the development of the larva and the pupation site. Walsh et al. (Reference Walsh, Arnold and Michaels2014) cite “M. Light in litteris” that S. ovata may have two generations per year but this would be unusual for a baridine weevil of the temperate zone.

Material examined. CANADA: Manitoba: Riding Mountain National Park, 9.vi.1937, W.J. Brown (CNCI, one specimen). Ontario: Campbellville, 24.v.1978, W.A. Attwater (CMNC, one specimen); 7 km W Carleton Place, 26.vi.1980, S.J. Miller (CNCI, one specimen); Dundas, 18.v.1979, K.L. Bailey (CMNC, one specimen); Erin, 17.vi.1979, J. Ernst (CMNC, one specimen); Foxboro, C.J. Edwards (CMNC, one specimen); Guelph, South Arboretum, 22.v.1985, B.V. Brown (CMNC, one specimen); Hamilton, 26.vi.1980, 16.vii.1980, 30.vi–8.vii.1981 (three specimens), 19–24.vii.1980 (two specimens), 12.vi.1980 (two specimens), 23.v–3.vi.1982, 23–29.v.1981 (two specimens), 7.vi.1981 (two specimens), 15.v.1981 (two specimens), 2–7.viii.1981, 14–19.vii.1981, 7.vi.1981, 28.vi–14.vii.1982, 23.vii.1980, 14–26.vii.1982, 28.vi.1980, M. Sanborne (CNCI, 23 specimens); Hamilton, 3.vii.1979, K.L. Bailey (CMNC, one specimen); Milton, 21–30.viii.1981, M. Sanborne (CNCI, one specimen); Ottawa, 24.vi.1995, 25.vii.1986 (five specimens), 27.v.1987 (four specimens), H. and A. Howden (CMNC, 10 specimens); Prince Edward County, 16.vi.1957, J.F. Brimley (CNCI, one specimen); Rondeau Provincial Park, 1–8.viii.1973, W.R. Mason (CNCI, one specimen); Rondeau Provincial Park, 2.vi.1985, L. LeSage (CNCI, one specimen); Rondeau Provincial Park, 1–9.viii.1985, L. LeSage and A. Woodliffe (CNCI, three specimens); Rondeau Provincial Park, 2–13.vii.1985 (CNCI, four specimens); Rondeau Provincial Park, 1–5.ix.1985 (CNCI, 1 specimen); Shirleys Bay, 15 km W Ottawa, 1.vii.1984, M. Kaulbars (CMNC, 27 specimens); Saint Lawrence Islands National Park, McDonald Island, 28.vii.1976, W. Reid (CNCI, two specimens); Saint Lawrence Islands National Park, Twarty Island, 15.viii.1976, 16.vii.1976, 6.viii.1976, (no date), A. Carter and W. Reid (CNCI, four specimens); Saint Lawrence Islands National Park, 20.vii.1976, W. Reid (CNCI, one specimen); Windsor, 23.vi.1985, B. Gill (CMNC, one specimen). Québec: Bécancour, 18.vi.1983, L. LeSage (CNCI, one specimen); Gatineau Park, Dannison Dam, 1–3.viii.1988, M. Light (CMNC, seven specimens); Hull, 28.vi.1965 (CNCI, one specimen); Montréal, 12.vi.1971, 2.vi.1972 (two specimens), 30.v.1972, 18.vi.1979, E.J. Kiteley (CNCI, five specimens); Notre-Dame-de-l’Ile-Perrot (Vaudreuil), 29.v.2012, P. de Tonnacour (CPTO, one specimen); Old Chelsea, Summit King Mountain, 16.vi.1965, D.D. Munroe (CNCI, one specimen); Terrasse-Vaudreuil (Vaudreuil), 20.vi.1994, P. de Tonnacour (CPTO, three specimens); Vercheres Varennes, 6.vi.2003, C. Chantal (CMNC, one specimen). New Brunswick: Edmundston, Madawaska County, 17.vi.2012, R. Migneault (bugguide.net/node/view/736340); Shepody National Wildlife Area, Mary’s Point section, 30.vii.2004, R.P. Webster (RPWC, one specimen). Nova Scotia: Debert, Colchert County, 23.vi.1995, E. Georgeson (NSNR, one specimen); Shubenacadie, Colchert County, 8.vii.1998, J. Ogden (NSNR, one specimen); Rear Estmere, Inverness County, Cape Breton, J.M. MacMillan, 9.vi.1996 (UCCB, one specimen); Sydney, Cape Breton, 19.vi.1995, B.L. Musgrave (UCCB, one specimen).

Stethobaris incompta Casey

Stethobaris incompta Casey, Reference Casey1892: 655.

Stethobaris commixta Blatchley, 1916: 407 (Blatchley and Leng Reference Blatchley1916). New synonym.

Diagnosis. Many S. incompta can be recognised by elongate confluent punctation on the pronotal flank. Towards the eastern and western perimeter of the range, this strigose surface changes gradually to an ordinary punctation similar to that present in the other two native species. In eastern Canada, such specimens can be distinguished with confidence from possibly co-occurring S. ovata by dissection of males and, with some practice, by comparing body shapes (Fig. 1–4). In western Canada, the only other species is S. sacajaweae, with shiny, longitudinally depressed elytral interstriae. Stethobaris corpulenta LeConte, 1876 from Florida and South Carolina, United States of America is very similar to non-strigose S. incompta but the penis is convex apically (notched in S. incompta, Fig. 7).

Figs. 1–6 Stethobaris, dorsal and lateral habitus. 1–2. Stethobaris ovata male. 3–4. Stethobaris incompta female. 5–6. Stethobaris sacajaweae male. Scale bar=1 mm.

Figs. 7–9 Stethobaris, aedeagus, dorsal view. 7. Stethobaris ovata. 8. Stethobaris incompta. 9. Stethobaris sacajaweae. Scale bar=0.2 mm.

Notes. Blatchley (Blatchley and Leng Reference Blatchley1916) proposed S. commixta for a species misidentified by Casey (Reference Casey1892) as S. ovata (LeConte Reference LeConte1869), based on the study of LeConte’s four syntypes, information provided in Casey (Reference Casey1892), and specimens of his own and F. Blanchard’s collections. Casey (Reference Casey1920) was unconcerned about the taxonomical aspects of this action but claimed his misidentified Massachusetts specimen to be the type for Blatchley’s species. This is unjustified because (i) it had not been included in the description and (ii) S. commixta did not replace an available name described from this particular specimen. A lectotype was designated by Blatchley (Reference Blatchley1922), which was cited again in Blatchley (Reference Blatchley and Leng1930) although with a different gender.

Casey and Blatchley each had one S. incompta that they distinguished from S. commixta by slightly different strial punctation. Because this character varies in the ~200 specimens examined by me, I consider S. commixta as a junior subjective synonym of S. incompta (new synonymy). The present location of Blatchley’s lectotype of S. commixta from Steuben County, Indiana, United States of America (and several other Baridinae described by him) is unknown to me. I tried to borrow this material from Purdue University (West Lafayette, Indiana, United States of America) four times in 2007–2008 and was told each time that it will be mailed. However, neither specimens nor loan documents arrived in the USNM so I was surprised when a newly hired collections manager inquired in 2013 (and another one again in 2014) about the material. Our research showed that the requested specimens were mailed on 23 April 2008 but not delivered to the USNM. It is unknown at present whether the box has been lost in the mail or was delivered elsewhere. Six paralectotypes of S. commixta, collected by F. Blanchard in Tyngsboro, are in the MCZ and were studied by me in 2012.

Distribution. Stethobaris incompta has a disjunct distribution in Canada. In the east, it occurs south of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and Saint Lawrence River. The species so far is unknown along the northern shores of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie but it might occur there as well. Western Canada has records from British Columbia to Saskatchewan except from the Great Plains. The gap between the western and eastern populations corresponds to the extent of the Laurentide Ice Sheet around 10 000 BC. The record from Jans Bay in Saskatchewan, at 55°N, represents the most northern find of any orchid weevil worldwide. In the United States of America, S. incompta occurs in the northeast (Connecticut, District of Columbia, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island), southeast (Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia), southwest (Oklahoma, Texas), northwest (Oregon, Washington), and central-north (Kansas, Missouri, North Dakota).

Natural history. The scarce information presently available stems almost entirely from orchid studies. Charles Dury (Blatchley and Leng Reference Blatchley1916) is said to have bred this weevil (described as S. commixta) in July from a species of Corallorhiza Gagnebin found in Balsam, North Carolina. However, this date appears rather early for the emergence of a specimen of the new generation. The reported host is, so far, the only record associating this weevil with an orchid in Epidendroideae. The following verified host associations all apply to Orchidoideae. Sieg and O’Brien (Reference Sieg and O’Brien1993) reported an association with Platanthera praeclara Sheviak and Bowles in a North Dakota tall-grass prairie. Their specimens (identified as S. commixta) were found in partially consumed flower buds during a study of the federally listed threatened host plant. Numerous independent observations (TAMU, label data) made in prairie habitats in Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas indicate that the weevil occurs also on species of Spiranthes Richard. The associations in Texas with Spiranthes cernua (Linnaeus) Richard, S. parksii Correll, and S. vernalis Engelmann and Gray were ascertained during a study of the endemic, federally listed threatened S. parksii (Navasota ladies tresses).

Material examined. British Columbia: Leanchoil, 30.v.1991, B.F. and J.L. Carr (CNCI, one specimen); Revelstoke, 15.v.1990, B.F. and J.L. Carr (CNCI, one specimen); Gabriola, 10.iv.1988, 2.vi.1991, B.F. and J.L. Carr (CNCI, two specimens). Alberta: Township 39 Range 7 W. 5 Meridian, 18.v.1992, B.F. and J.L. Carr (CNCI, one specimen); Ghost Dam, 10.vi.1980, 11.vi.1980 (two specimens), 13.vi.1980, 25.v.1983, 1.vi.1992, B.F. and J.L. Carr (CNCI, six specimens); Calgary, 24.vi.1964, 2.vi.1968, B.F. and J.L. Carr (CNCI, two specimens). Saskatchewan: Road 965, 14 km W junction road 155, 1.viii.1986, B.F. and J.L. Carr (CNCI, one specimen). Ontario: Ottawa, Mer Bleue bog, 30.iv.1982, L. LeSage (CNCI, one specimen). Québec: Mont Orford, Sherbrooke County, 30.vi.1984, Larochelle and Larivière (CNCI, one specimen); Ormstown, 8.vii.1983, E.J. Kiteley (CNCI, one specimen). New Brunswick: Bathurst, 9.vii.1939, W.J. Brown (CNCI, one specimen); Kouchibouguac National Park, 26.vi.1977, D.M. Wood (CNCI, one specimen).

Stethobaris sacajaweae Prena, new species

Diagnosis. Stethobaris sacajaweae is a western species with slightly depressed and moderately punctate elytral interstriae. This and the usually pronounced sheen separate S. sacajaweae from S. incompta in western Canada and from S. egregia in the southwestern United States of America. The penis is apically convex in S. sacajaweae (Fig. 9) and slightly notched in S. incompta and S. egregia. Other morphologically similar species occur throughout the Neotropics (among them the type species of Montella Bondar) but have flat or convex interstriae.

Description. Body oblong-oval, convex, subglabrous, shiny with obsolete micropunctation at 40× magnification; colour piceous (nearly black). Rostrum as long as pronotum, moderately curved in lateral view, not distinctly sexually dimorphic. Antenna inserted at midlength of rostrum, funicle stout, antennomere 1 as long as next three, antennomeres two to seven short, progressively wider towards club; antennal club moderate, oval, in both sexes as long as preceding six antennomeres; prothorax 1.24–1.29× as wide as long, sides gradually converging in basal half and then abruptly curved inward to subapical constriction. Pronotal disc with punctures slightly smaller than those in elytral striae, punctures coarser and denser on flank but well defined and not confluent to ridges. Scutellum rectangular. Elytra 1.20–1.23× as wide as prothorax, humeral callus moderately developed, striae coarse and deep, with edges not crenulate-punctate except near base, interstriae concave in cross-section, finely (on disc) to moderately (towards flank) punctate, male interstria 9 with distal three to four punctures modified to continuous sulcus; metepisternum with punctures dense. Tarsal claws divergent and basally separate, of equal length. Aedeagus as in Figure 9; total length (without rostrum) 2.9–3.2 mm, standard length (without head) 2.7–3.0 mm, width 1.6 mm.

Distribution. Stethobaris sacajaweae occurs on the Pacific side of the Rocky Mountains, from British Columbia south to California, United States of America.

Natural history. Elwood Zimmerman collected two specimens from Corallorhiza maculata (Rafinesque) Rafinesque in Ridge, California (label data).

Type material. Holotype: Female, labelled “Salmon Arm / BC 1933 / Smith” (CNCI). Paratypes 10 (five males, five females): California: Challenge, Yuba County, 28.v.1963, E.E. Ball (AMNH, one male, one female); California: Challenge, Yuba County 7.vi.1963 (AMNH, one female; CWOB, two females); 7.5 miles NE Alexander Valley, Pine Flat Road, Sonoma County, 5.v.1967, W. Gagné (CWOB, one female); Ridge, Mendocino, 1.v.1933, E. Zimmerman (USNM, two males); Yosemite, 17.v.1928, E. Zimmerman (USNM, one male); Bridgeville, 20.vi.1959, Kelton and Madge (CNCI, one male); Forest Grove, Washington County, 19.iv.1918, L.P. Rockwood (USNM, one female); Washington: Thurston County, Grand Mound, 5.iv.1930, W. Baker (USNM, one female).

Etymology. The epithet is a patronym given in memory of Sacajawea (“Bird Woman” in the language of the Hidatsa tribe that abducted her as a child), a courageous Shoshone woman who was recruited by the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1804. Clark later adopted her two children.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Bob Anderson (CMNC), Pat Bouchard (CNCI), Lee Herman (AMNH), Henry Hespenheide (Los Angeles, California, United States of America), the late Anne and Henry Howden (CMNC), Charlie and Lois O’Brien (CWOB), Phil Perkins (MCZ), Ed Riley (TAMU), Paul Skelley (Gainesville, Florida, United States of America), and Jim Wappes (San Antonio, Texas, United States of America) who provided specimens or access to them. Pat Bouchard also helped find field observations made by the late John Carr of Calgary, Alberta. Rick Westcott (Salem, Oregon, United States of America) was very kind and searched for specimens in the collection of the Oregon State Department of Agriculture, Salem. I also acknowledge the immensely useful contribution of ecological data by the community of orchid researchers, such as Robert Dressler, Marilyn Light, Michael MacConaill, Joyce and Allan Reddoch, and Ryan Walsh, even though they (understandably) may not be particularly fond of orchid-eating weevils. Two reviewers and the subject editor provided thoughtful comments.