Introduction

The Nymphidae (split-footed lacewings) is a small family of medium-sized to large-sized Neuroptera with eight extant genera and 35 extant valid species. They are currently restricted to Australia and adjacent islands, New Guinea (New Reference New1982a, Reference New1985, Reference New1986a, Reference New1988; Oswald Reference Oswald1997, Reference Oswald1998; Global Biodiversity Information Facility 2019), and possibly the Philippines but that record is doubtful (New Reference New1982a). The extant genera of Nymphidae are divided into two distinct subfamilies, Nymphinae and Myiodactylinae (New Reference New, Gepp, Aspöck and Hölzel1984; Shi et al. Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015), which were once considered as separate families (e.g., Tillyard Reference Tillyard1926). The Nymphinae comprises three extant genera (Nymphes Leach, Austronymphes Esben-Petersen, and Nesydrion Gerstaecker), and Myiodactylinae, the other five.

The Nymphidae were relatively diverse in the Mesozoic (Table 1). Twenty species have been described from their earliest appearance in the Middle Jurassic through the Late Cretaceous (Turonian) (Carpenter Reference Carpenter1929; Panfilov Reference Panfilov, Dolin, Panfilov, Ponomarenko and Pritykina1980; Makarkin Reference Makarkin1990a, Reference Makarkin and Akimov1990b; Ponomarenko Reference Ponomarenko1992; Martins-Neto Reference Martins-Neto2005; Ren and Engel Reference Ren and Engel2007; Engel and Grimaldi Reference Engel and Grimaldi2008; Makarkin et al. Reference Makarkin, Yang, Shi and Ren2013; Shi et al. Reference Shi, Makarkin, Yang, Archibald and Ren2013, Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015; Myskowiak et al. Reference Myskowiak, Huang, Azar, Cai, Garrouste and Nel2016). Their fossils are, however, rare in the Cenozoic, with only three species known, each represented by single, incomplete adult specimen: Nymphes? georgei Archibald, Makarkin, and Ansorge from the Ypresian (early Eocene) Okanagan Highlands locality at Republic (Washington, United States of America), and two species of the genus Pronymphes Krüger from Priabonian (late Eocene) Baltic amber: P. mengeana (Hagen) and P. hoffeinsorum Archibald, Makarkin, and Ansorge (Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Makarkin and Ansorge2009). The single known larva from Baltic amber is also considered to belong to Pronymphes (MacLeod Reference MacLeod1971). Here, a fourth adult specimen is described from the Ypresian Okanagan Highlands of Falkland, British Columbia, Canada, representing a new genus and species. We further evaluate the subfamily affinities of Cenozoic and Mesozoic fossil Nymphidae and their biogeographic implications. The generic affinities of some Mesozoic species are revised.

Table 1. Fossil species of Nymphidae.

1Ren and Engel (Reference Ren and Engel2007); 2Makarkin et al. (Reference Makarkin, Yang, Shi and Ren2013); 3Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Cai, Fu and Su2018); 4Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Makarkin, Yang, Archibald and Ren2013); 5Panfilov (Reference Panfilov, Dolin, Panfilov, Ponomarenko and Pritykina1980); 6Rasnitsyn and Zherikhin (Reference Rasnitsyn, Zherikhin, Rasnitsyn and Quicke2002); 7Carpenter (Reference Carpenter1929); 8Schweigert (Reference Schweigert2007); 9Weyenbergh (Reference Weyenbergh1869); 10Westwood (Reference Westwood1854); 11Jepson et al. (Reference Jepson, Makarkin and Coram2012); 12Ponomarenko (Reference Ponomarenko1992), generic placement unresolved; 13Bugdaeva and Markevich (Reference Bugdaeva, Markevich and Godefroit2012); 14Makarkin (Reference Makarkin1990a); 15Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015); 16Makarkin et al. (Reference Makarkin, Yang, Peng and Ren2012); 17Martins-Neto (Reference Martins-Neto2005); 18Martill and Heimhofer (Reference Martill, Heimhofer, Martill, Bechly and Loveridge2008); 19Myskowiak et al. (Reference Myskowiak, Huang, Azar, Cai, Garrouste and Nel2016); 20Engel and Grimaldi (Reference Engel and Grimaldi2008); 21Makarkin (Reference Makarkin and Akimov1990b); 22Makarkin and Khramov (Reference Makarkin and Khramov2015); 23Moss et al. (Reference Moss, Greenwood and Archibald2005); 24Archibald et al. (Reference Archibald, Makarkin and Ansorge2009), generic placement uncertain; 25Wolfe et al. (Reference Wolfe, Gregory-Wodzicki, Molnar and Mustoe2003); 26Pictet-Baraban and Hagen (Reference Pictet-Baraban, Hagen and Berendt1856); 27Krüger (Reference Krüger1923); 28Perkovsky et al. (Reference Perkovsky, Rasnitsyn, Vlaskin and Taraschuk2007).

Material and methods

This study is based on a single specimen in lacustrine shale from a locality near Falkland, British Columbia, Canada.

Locality

This site is in the middle of the southern half of the Okanagan Highlands series of Ypresian upland lacustrine shale and coal basins that are scattered over about 1000 km of south-central British Columbia, Canada, from Driftwood Canyon near the village of Smithers in west-central British Columbia to just over the international border at Republic, Washington, United States of America (Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Greenwood, Smith, Mathewes and Basinger2011a). The locality is about 220 km northwest of Republic. It is a small, difficult to access exposure of Kamloops Group lacustrine shale on Estekwalan Mountain about 5 km northwest of the village of Falkland, British Columbia.

Uranium–lead dating from zircons recovered from an ash layer intercalated within the fossil-bearing sediment indicates an age of 50.61 ± 0.16 million years ago (see Moss et al. Reference Moss, Greenwood and Archibald2005). Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Basinger and Greenwood2009) estimated a paleoelevation of greater than 1.3 km, similar or slightly higher than modern levels, and provided estimates of an upper microthermal mean annual temperature, slightly varying by method of analyses (microthermal: mean annual temperature ≤ 13 °C).

Although Falkland fossil insects are plentiful (S.B.A., personal observation), they have received relatively little attention. They were first mentioned by Rice (Reference Rice1959) who named a species of Bibionidae (Diptera) from the site (Plecia cairnesi Rice). The fossils that he reported were collected “northwest of Falkland” by Geological Survey of Canada geologists in 1932, though it is not clear whether this was the same exposure referred to here, and there are other local exposures more readily accessible. Rice (Reference Rice1959) was referenced by Wilson (Reference Wilson1977) and Douglas and Stockey (Reference Douglas and Stockey1996) in their lists of insect-bearing deposits in British Columbia, but they did not collect there or report new taxa.

The site was shown to one of us (S.B.A.) by a local resident in June 2001. The major subsequent focus on it in recent decades has been on its plants (Moss et al. Reference Moss, Greenwood and Archibald2005, Reference Moss, Smith and Greenwood2016; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Basinger and Greenwood2009, Reference Smith, Greenwood and Basinger2010, Reference Smith, Basinger and Greenwood2012). Its few subsequently published insects include a bulldog ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmeciinae: Myrmeciites Archibald, Cover, and Moreau; Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Cover and Moreau2006), a scorpion fly (Mecoptera: Eorpidae: Eorpa Archibald, Mathewes, and Greenwood; Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Mathewes and Greenwood2013), and a parasitoid wasp (Hymenoptera: Trigonalyidae; Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Rasnitsyn, Brothers and Mathewes2018).

The only known other Neuropteran specimen from Falkland is a poorly preserved, undescribed Chrysopidae probably belonging to the Ypresian genus Adamsochrysa Makarkin and Archibald (current research).

Terminology

Venational terminology follows Makarkin et al. (Reference Makarkin, Heads and Wedmann2017). That of wing spaces and finer details of venation (e.g., veinlets, traces) follows Oswald (Reference Oswald1993). Contrary character states of compared taxa are provided in brackets.

Abbreviations: AA1–AA3, first to third anterior analis; CuA, anterior cubitus; CuA1, first (proximal-most) branch of CuA; CuP, posterior cubitus; MA and MP, anterior and posterior branches of the media (M); MP1, proximal-most branch of MP; RA, anterior radius; RP, posterior radius; RP1, proximal-most branch of RP; ScP, posterior subcosta; sv, subcostal veinlets.

Institutional abbreviations: GSC, Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; PIN, Borissiak Paleontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia.

Epinesydrion Archibald and Makarkin, new genus (Nymphidae: Nymphinae)

http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:2C1DAB84-3B3B-4F51-8848-E51B99911C4D

Diagnosis

May be distinguished from other genera of the family by a combination of the following wing characters (see detailed comparison of the new genus in Discussion): Forewing: costal space relatively narrow; RP1 originating very far from wing base (distad origin of CuA1); M forked proximad origin of CuA1; MA, MP, anterior trace of branched portion of CuA arched; no crossvein between the branches of CuA; all anal veins forked. Hind wing: RP originating near wing base; presectoral crossveins (i.e., those between R and M proximad origin of RP) absent.

Etymology

From the Greek epi [επι], near, and Nesydrion, a genus-group name. Gender masculine.

Type and only species

Epinesydrion falklandensis new species, here designated.

Epinesydrion falklandensis Archibald and Makarkin, new species

http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:CE2A7BF9-9888-44A7-8EB6-6C4F66E23739

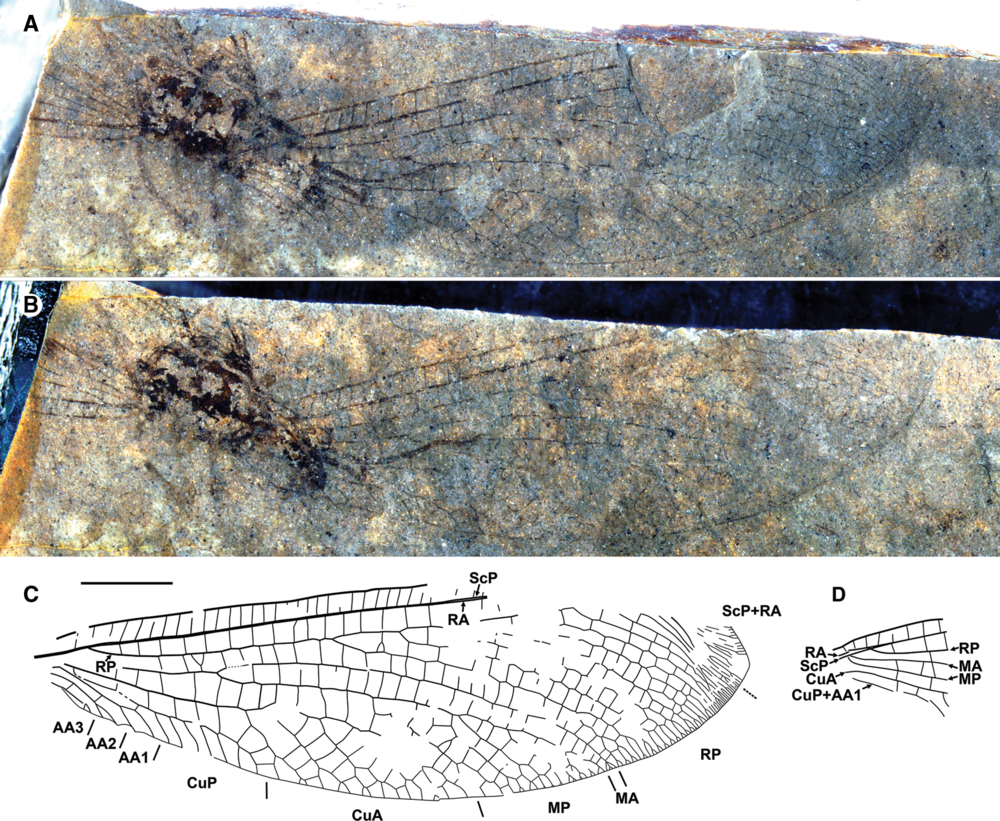

Fig. 1. Epinesidrion falklandensis new genus, new species, holotype. A, Part GSC 141064 A (converted to standard view, with apex to the right); B, counterpart GSC 141064 B; C, venation of the right forewing; D, venation of the right hind wing. Scale bar 5 mm (all to same scale).

Fig. 2. Epinesidrion falklandensis new genus, new species, holotype. A, Right hind wing of the part GSC 141064 A (converted to standard view, with apex to the right); B, same of the counterpart GSC 141064 B. Scale bar 1 mm (both to same scale).

Diagnosis

See genus diagnosis.

Material

Holotype: GSC 141064A, B (part and counterpart) was collected on 5 July 2006, by S.B. Archibald and deposited in the GSC type collections. An incompletely preserved specimen with a head, thorax with three or four very poorly preserved legs, the mostly complete right forewing, the basal portion of the right hind wing, and the fragmentary basal portions of the left wings.

Etymology

The specific epithet is a toponym formed from the name of the locality of the holotype.

Type locality and age

Falkland, British Columbia, Canada, GSC locality number V-016727; late Ypresian.

Description

Head: indistinctly preserved; diameter of eye approximately half head length. Antennae about 10 mm long, details not discernible.

Thorax: Pronotum poorly discernible. Mesonotum and metanotum dark laterally, pale medially, forming broad pale medial stripe through at least pteronotum (but possibly an artefact).

Legs: Poorly preserved, no details discernible.

Forewing: Broadly oval with apex distinctly pointed. Length 40 mm, maximum width 12 mm at mid-wing. Trichosors poorly discernible (proximally along posterior margin not discernible, distally one trichosor between each pair of veins, poorly preserved). Macrotrichia on veins, margins almost not discernible (poorly preserved and/or short). Costal space relatively narrow, even width from near base to 2/3 wing length (apicad this, not preserved). All preserved sv are simple, rather straight, closely spaced. Posterior subcosta and R/RA are close, possibly touching, appearing as single vein without space between them (i.e., subcostal space compressed) through almost all preserved portions of the wing (basal 2/3) but slightly separate basally. ScP + RA terminates at the margin beyond the apex. ScP + RA veinlets are indistinctly preserved but some deeply forked. All appear to have shallow forks near margin. Anterior radius space uniformly wide through middle half of the wing, with 11 crossveins regularly spaced between RA and RP before the origin of RP1. Presectoral crossveins are absent. Posterior radius originates close to the wing base; anterior trace of RP with nine branches, all dichotomously branched distally at different distances from the margin (RP1, RP5 most deeply branched). The proximal-most branch of RP originates at 43% of wing length. Media is deeply forked, half-way between level of origin of RP, origin of RP1, and proximad CuA1. The anterior branch of the media is arched, simple, with only shallow end-twigging. The posterior branch of the media is arched, parallel to MA, with six branches, all (except distal-most) dichotomously forked at different distance from the margin. The posterior branch of the media space is rather broad, triangular. Numerous crossveins in radial to medio-cubital spaces, not arranged in distinct gradate series. The cubitus is divided into CuA and CuP near the wing base (basad origin of RP). The CuA space is broad, triangular. Anterior trace of CuA slightly incurved before the origin of CuA1, arched after; with five branches, each forking again two to three times near margin; all connected by numerous crossveins. The CuA and CuP are connected by numerous crossveins (eight in right wing). The CuP has seven pectinate branches, none connected by crossveins. There is a single crossvein preserved between CuP, AA1 (2cu-aa), connecting CuP and the anterior trace of AA1; a basal crossvein (1cu-aa) is possible at the point where CuP and AA1 are closest. The AA1, AA2 and AA2, AA3 are each connected by a single, long crossvein. The AA1 is rather deeply forked once; AA2 and AA3 are more shallowly forked once. Wing membrane apparently hyaline throughout as preserved.

Hind wing: Basal-most fragment is preserved, likely somewhat torn; apparently the ScP is positioned posteriad RA by damage (Figs. 1–2). Costal space is relatively narrow. Subcostal veinlets are simple, straight. Basal portions of MA and MP are obscured; the fork of M is not visible, apparently very near the wing base. The RP originates near the wing base; no presectoral crossveins are detected. Basal portions of CuA, CuP + AA1 are preserved. Crossveins between RA to CuP are relatively scarce. Wing membrane apparently hyaline.

Discussion

The validity and relationship of Epinesydrion

Two genera of Nymphidae were previously known from the Eocene: the extant Nymphes from the Okanagan Highlands of North America (but see below) and the extinct Pronymphes from Priabonian Baltic amber (Krüger Reference Krüger1923; Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Makarkin and Ansorge2009). A larva from Baltic amber was assigned to Pronymphes (see Weidner Reference Weidner1958, fig. 7; plate 14, figs 4–5; MacLeod Reference MacLeod1971, figs. 5–7). Pronymphes and Epinesydrion confidently belong to the Nymphinae, possessing diagnostic character states of the subfamily (see below). Both are clearly similar to the nymphine genus Nesydrion (four extant Australian species). These three genera share two forewing character states: the deeply forked M [shallowly forked in Nymphes and Austronymphes] and a lack of crossveins between the branches of CuP [present in Nymphes].

Epinesydrion differs from Nesydrion and Pronymphes by MA, MP, and a part of the anterior trace of CuA, distad CuA1 being clearly arched, and by its triangular CuA space. This triangular CuA space is also characteristic of Nymphes, which, however, differs from Epinesydrion in other ways (e.g., as above). Three of four species of Nesydrion possess one to three presectoral crossveins in the hind wing, but no presectoral crossveins are found in Epinesydrion. The colour pattern of the mesonotum and metanotum of Epinesydrion falklandensis (i.e., dark entirely or only laterally with possible pale broad medial stripe) also strongly differs from that of any species of Nesydrion where this is generally pale but sometimes with a dark median stripe.

It is noteworthy that, except at the base, ScP and R/RA appear fused and so the subcostal space appears missing. Such an apparent fusion of these veins also occurs in the holotype of the Late Jurassic Nymphites priscus (Weyenbergh) (see Shi et al. Reference Shi, Makarkin, Yang, Archibald and Ren2013, figs. 1–2). The subcostal space is clearly discernible (often well developed) in all other fossil species except the proximal basal part of Nymphes? georgei (generic classification uncertain), which is missing in its only known fossil (see Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Makarkin and Ansorge2009, fig. 1A). We believe it to be likely that this close approach of ScP and RA in Epinesydrion indicates the absence of subcostal crossveins in the space or at least the presence of very short thyridiate crossveins (incomplete crossveins that allow folding or bending of the wing). In all species of Nesydrion, there are numerous thyridiate crossveins in the subcostal space, which often almost reach RA but do not touch it (Shi et al. Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015). This suggests that the apparent lack of the subcostal space may be an artefact resulting from the space collapsing postmortem due to the absence of structural support from the connecting crossveins.

The forewings of Epinesydrion differ from those of all Mesozoic genera by their triangular CuA space and CuA1 originating only slightly distad the fork of M. The origin of CuA1 is located far distad the fork of M in all Mesozoic genera except in Baissoleon Makarkin and Olindanymphes Martins-Neto. Further, M in these genera is strongly arched as in Epinesydrion. Their CuPs, however, have only one to two branches, whereas it is strongly pectinate in Epinesydrion, with six branches.

Epinesydrion is, therefore, clearly a distinct genus. As above, the proximal forking of M suggests that it is closely related to Nesydrion and Pronymphes but more distantly to them than they are to each other because of the triangular CuA space in the forewing, a certainly apomorphic state occurring within the family that these do not possess. However, this is shared by Nymphes, which alternatively suggests that Epinesydrion is more closely related to it.

It should be noted that the genus Nymphes has been reported from the nearby Okanagan Highlands locality at Republic (N.? georgei), which is nearly of the same age (Fig. 3) (Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Makarkin and Ansorge2009). Unfortunately, this record is of a single hind wing that lacks the basal portion, precluding comparison of key character states with Epinesydrion falklandensis. Therefore, N.? georgei could belong to Epinesydrion and so we treat it here as a species of uncertain generic placement. No preserved morphology rules out this possibility. Resolving this requires the discovery of a comparable forewing of N.? georgei or of a more complete hind wing of Epinesydrion.

Fig. 3. Distribution of fossil and extant Nymphidae. Jurassic localities (black dots): 1, Daohugou, China; 2, Karatau, Kazakhstan; 3, Solnhofen, Germany. Cretaceous localities (blue dots): 4, Durlston Bay, United Kingdom; 5, Baissa, Russia; 6, Yixian Formation, China; 7, Crato Formation, Brazil; 8, Burmese amber, Myanmar; 9, Arkagala Formation, Russia. Cenozoic localities (brown dots): 10, Falkland, Canada; 11, Republic, United States of America; 12, Baltic amber. The present-day distribution is shown in red.

Diversity of Nymphidae

This family is monophyletic based on two putative synapomorphies of adults: the presence of thyridiate crossveins in the subcostal space and their possession of a bifid arolium (Shi et al. Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015). However, such crossveins or a bifid arolium have not been detected with confidence in fossil species. Carpenter (Reference Carpenter1929, fig. 1) figured the crossveins in this position as complete in Mesonymphes hageni Carpenter, and Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Makarkin, Yang, Archibald and Ren2013) speculated that thyridiate crossveins are “probably” present in Nymphites bimaculatus Shi, Makarkin, and Ren as its ScP possesses few, small projections posteriorly. Nevertheless, fossil specimens may be confidently assigned to Nymphidae by the following combination of wing character states: (1) ScP and RA are distally fused; (2) ScP + RA enters the wing margin posteriad the apex; (3) trichosors are present; (4) M originates near the wing base (there are no presectoral crossveins), and (5) M is not fused with CuA in the forewing. Only Nymphidae and all Nymphidae share this combination except Baissoleon, where ScP + RA enters the wing margin before the apex (it is assigned to the family by characters 1, 3–5, and general similarity of the venation to that of Nymphidae, for example, by the nonpectinate AA1 in the forewing [pectinate in all Osmylidae possessing characters 1, 3–5]).

Extant

Extant Nymphidae form two distinct groups of genera, which constitute the subfamilies Myiodactylinae and Nymphinae. According to Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015), the species of Nymphinae are easily distinguished from those of the Myiodactylinae by: (6) the presence of tibial spurs, at least on the hind legs [absent]; (7) the narrow costal space in the forewing [broad, often with multiple forked sv]; (8) crossveins between the branches of CuA in the forewing [absent]; (9) short AA1 in the forewing [long]; and (10) at least several rows of linking crossveins between branches of MP in the hind wing [few linking crossveins]. They also differ in the morphology and behaviour of the larvae. Those of Myiodactylinae are rounded and flattened dorsoventrally (New Reference New1983; New and Lambkin Reference New and Lambkin1989) and are arboreal, living on leaves (in Osmylops Banks, with a green body) or dwell in the litter (those of Norfolius Navás are brown). The larvae of Nymphinae (known only in Nymphes) are elongate, dwell in the litter, and carry debris for camouflage (New Reference New1982b, Reference New1986b).

Cenozoic

Based on these adult character states, both Epinesydrion and Pronymphes – the Nymphidae genera known only as fossils in the Cenozoic – may be assigned to Nymphinae with certainty, as they conform to all of these, except that the presence or absence of tibial spurs (character 6) and hind wing crossvenation (character 10) cannot be assessed in Epinesydrion by preservation, and the hind wing MP branches (character 10) in Pronymphes are connected by only a single row of linking crossveins. Pronymphes does, however, possess tibial spurs (Pictet-Baraban and Hagen Reference Pictet-Baraban, Hagen and Berendt1856). The Baltic amber larva tentatively assigned to Pronymphes clearly belongs to the Nymphinae by its elongate body, the rugose texture of the cuticle of the head, the presence of distinct dorsal and ventral rows of lateral scoli on the abdomen, and the vestiture of setae with globular tips as in Nymphes (MacLeod Reference MacLeod1971). However, as Nymphes is the only extant nymphine genus whose larva has been described, the position of this larva within the subfamily remains unresolved.

Mesozoic

The subfamily assignments of almost all Mesozoic genera are more problematic than are those of the Cenozoic. Makarkin (Reference Makarkin and Akimov1990b) suggested that Dactylomyius Makarkin (Fig. 3) probably belongs to the Myiodactylinae, and Mesonymphes Carpenter certainly to the Nymphinae. Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015) made the first attempt to resolve the phylogeny of the family, including the five Mesozoic genera. They assigned Baissoleon, Sialium Westwood, and Nymphites Haase to the Nymphinae; Spilonymphes Shi, Winterton, and Ren to the Myiodactylinae; and Liminympha Ren and Engel were considered sister to Nymphinae + Myiodactylinae (see Shi et al. Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015, fig. 5). Below, we evaluate the subfamily and genus assignments of all Mesozoic genera and conclude that some of these may be incorrect.

All Mesozoic genera are at least superficially similar in some ways to the Nymphinae except Dactylomyius from the Late Cretaceous of northeastern Siberia. As in the Nymphinae, their wings are relatively narrow, and tibial spurs are preserved in some species (e.g., Nymphites bimaculatus, Baissoleon similis Shi, Winterton, and Ren). Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015) treated the presence of these spurs as apomorphic in the Nymphinae; however, it is plesiomorphic, as it is present in all families of Neuropterida (including extinct families wherever legs are preserved well enough to evaluate), and their absence (including in the Myiodactylinae) is an apomorphy.

The relatively narrow wing shape of Mesozoic genera is a generalised condition, which often occurs in the order and so lacks diagnostic value in resolving their subfamily affinities. Even in extant taxa, forewings of nymphine species are sometimes broader than those of myiodactyline species (e.g., length/width ratio is 2.99 in Nesydrion diaphanum Gerstaecker, and 3.20 in Osmylops ectoarticulatus Oswald), though the forewings in the Myiodactylinae are usually broader than those of Nymphinae.

The venation of Mesozoic taxa varies to a large extent among genera. The monotypic genus Dactylomyius differs most strongly. It is known by the mostly complete, broad hind wing of D. septentrionalis Makarkin (Fig. 3). Its venation is most similar to that of Myiodactylus, especially by its dilated costal space, dense crossvenation, and wing shape but differs by its nonpectinate MP [pectinate in Myiodactylus], the broad space between CuA and CuP [narrow in Myiodactylus], and the very long CuA with its distal branches strongly curved anteriorly [moderately long with all branches only slightly curved in Myiodactylus]. Reexamination of the holotype shows that the interpretation of the veins by Makarkin (Reference Makarkin and Akimov1990b) was partly incorrect: the anterior branch of MP in that work is actually MP; the posterior branch of MP is actually CuA; Cu is actually CuP or CuP + AA1; and A1 is probably AA2. This is supported by CuA being clearly concave, as is characteristic of the hind wings of all Neuroptera (see Makarkin et al. Reference Makarkin, Ren and Yang2009). This is perhaps the single fossil genus whose assignment to the Myiodactylinae appears possible, even though it bears a number of notable dissimilarities in its venation with Myiodactylus.

Fig. 4. Dactylomyius septentrionalis Makarkin, the sole fossil species possibly belonging to the Myiodactylinae, holotype PIN 1832/7. A, Photograph; B, drawing. Scale bar 5 mm (both to same scale).

Other Mesozoic genera are superficially similar to the Nymphinae, and most may be divided into four groups.

(1) The Middle Jurassic to Early Cretaceous Liminympha Ren and Engel, Daonymphes Makarkin, Yang, Shi, and Ren, Nymphites, Mesonymphes, Sialium, and Spilonymphes. These form a relatively homogeneous group characterised by a very deeply forked M; MA with few branches; MP and CuA are pectinate, with long branches; the origin of CuA1 is located far distad the fork of M; CuP is strongly pectinate; and AA1 is often relatively strongly branched (forked two to three times, rarely more). Their general venation pattern is clearly more similar to that of Nymphinae than Myiodactylinae. However, some features contradict this. For example, AA1 has more branches than in extant Nymphinae (similar to the condition seen in the myiodactyline Osmylops). Also, there is only one row of crossveins between branches of MP in the hind wings, not several as in extant genera of Nymphinae. It is possible that all genera of this group belong to stem Nymphidae or are sister to Myiodactylinae + Nymphinae.

Of these, only Liminympha was considered as sister to the remaining Nymphidae by Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015), presumably based on a recurrent humeral veinlet, no crossveins between distal branches of RP, and the antennae longer than half wing length (an apomorphy shared with the extant Nymphes aperta New). However, the head with antennae is missing in both the part and the counterpart (see the photograph of the part in Ren and Engel (Reference Ren and Engel2007, fig. 1) and of the counterpart in Makarkin et al. (Reference Makarkin, Yang, Shi and Ren2013, fig. 3)), so we assume that the apparent long antennae of the original description are actually artefacts of preservation. The humeral veinlet is recurrent in Liminympha makarkini Ren and Engel, Daonymphes bisulca Makarkin, Yang, Shi, and Ren and Sialium sinicus Shi, Winterton, and Ren, while it is crossvein like in all other Nymphidae. It is not branched or has a single, short branch (in Daonymphes). The presence of the recurrent humeral veinlet is probably a symplesiomorphy of the family. The absence of crossveins between distal branches of RP appears to be a good character to help separate genera but probably nothing more. By these reasons, consideration of Liminympha as the single sister genus to the remaining Nymphidae appears insufficiently based.

The genus Spilonymphes (with one species: Spilonymphes major Shi, Winterton, and Ren) was assigned to the Myiodactylinae by Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015). We believe that this is incorrect. Indeed, the venation of S. major does not significantly differ from that of Sialium minor Shi, Winterton, and Ren, which was considered to belong to Nymphinae by Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015). Here, we transfer S. minor to the genus Spilonymphes, in particular based on the presence of an important synapomorphy: the hind wing intramedian space is slightly but clearly expanded in the region of the origin of MP1, and distad this MP is slightly curved in both S. minor and Spilonymphes major (and see below). Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015) assigned Spilonymphes to the Myiodactylinae based solely on its slightly broader forewing in the costal space than is typical of Nymphinae genera; however, they mentioned that such a forewing costal space is present in some other Mesozoic genera (e.g., Daonymphes and Elenchonymphes Engel and Grimaldi). Moreover, this space is not especially broad; it is nearly of the same width as in, for example, Nymphites and Mesonymphes. These two congeneric species have been assigned to two subfamilies; we believe that they belong to neither.

(2) The Early Cretaceous genus Cretonymphes Ponomarenko, represented by three specimens of C. baisensis Ponomarenko, possesses a forewing (the holotype) and two isolated hind wings (Ponomarenko Reference Ponomarenko1992, fig. 1). These share a similar dense crossveins throughout. However, the holotype may not be conspecific or even congeneric with the hind wings (which belong to a single species with certainty). The forewing differs from that of the previous group by the forking of M slightly distad, its pectinate MA and its MP with few pectinate branches. By these reasons, Cretonymphes baisensis is most similar to Rafaelnymphes cratoensis Myskowiak, Huang, Azar, Cai, Garrouste, and Nel. The hind wing is unique within the family, as its CuP is strongly pectinate, with 13 branches. All other Nymphidae (including the oldest) have their hind wing CuP with a maximum of two branches, except Sialium sinicus, whose pectinate CuP bears five to six branches. If these three wings belong to the same species, then Cretonymphes should be considered as stem Nymphidae. If not, only the hind wings belong to stem Nymphidae, whereas the forewing may be tentatively assigned to crown Nymphinae by the narrow costal space and the presence of crossveins between branches of CuA in the forewing.

(3) The Early Cretaceous Rafaelnymphes cratoensis (Myskowiak et al. Reference Myskowiak, Huang, Azar, Cai, Garrouste and Nel2016). It is the single fossil species (and genus) whose M in the forewing is forked in its distal part (much distad the origin of RP). In this aspect, its venation is most similar to that of some species of Nymphes, differing mainly by the configuration of its CuA. Therefore, the nymphine assignment of the genus appears reasonable. However, although the legs are partly present in this fossil, tibial spurs were not detected (possibly, however, because of their small size). Also, the hind wings appear markedly longer than the forewings in the resting position (i.e., they are slightly longer, or at least not shorter than the forewings), while lengths of the forewings and hind wings of all extant Nymphinae (and Nymphidae) appear equally long in the resting position (i.e., the hind wings are actually shorter than the forewings) (see Myskowiak et al. Reference Myskowiak, Huang, Azar, Cai, Garrouste and Nel2016, figs. 4–5). Despite this, Rafaelnymphes Myskowiak, Huang, Azar, Cai, Garrouste, and Nel may be tentatively assigned to Nymphinae by the narrow costal space and the presence of crossveins between branches of CuA in the forewing.

(4) The Early Cretaceous genera Baissoleon and Olindanymphes (Makarkin Reference Makarkin1990a; Martins-Neto Reference Martins-Neto2005). These are probably closely related. They are smaller than other Mesozoic genera and differ further from them by the forewing CuP with few branches (one to two), a distinct pterostigmata in both wings, and ScP + RA entering the margin before the apex (slightly beyond the apex in Olindanymphes). The forewing with a pectinate CuP and ScP + RA entering the margin far beyond the wing apex is characteristic of all extant genera of both subfamilies. By these reasons, we find the assignment of Baissoleon to the Nymphinae Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015) to be uncertain. We believe it more likely that these two genera belong to stem Nymphidae.

The systematic positions of Elenchonymphes and Santananymphes Martins-Neto are unclear, and they might be associated with any or none of the above genera.

Elenchonymphes was described based on the distal 2/3 of the forewings and hind wings of the type species E. electrica Engel and Grimaldi, from earliest Late Cretaceous Burmese amber. The preserved venation of both wings appears rather atypical (e.g., the RA space is narrowed at the distal crossvein in both wings, and CuA is strongly incurved in the forewing).

Four larvae from Burmese amber described as Nymphavus progenitor Badano, Engel, and Wang were assigned to the Nymphinae. They have the typical morphology of the subfamily, differing only in details (Badano et al. Reference Badano, Engel, Basso, Wang and Cerretti2018, figs. 3c, S1h, S2a [not S2e as cited by them]). They are, however, represented by different instars, which might not belong to a single species and even genus; they might even be conspecific with E. electrica.

Santananymphes ponomarenkoi Martins-Neto was inadequately described, and so its systematic position cannot be evaluated without examination of the holotype.

In summary, the great majority of fossil genera may be assigned either to stem Nymphidae (most Mesozoic genera) or to Nymphinae (Late Cretaceous Burmese amber larvae, tentatively the Early Cretaceous Rafaelnymphes, and all Cenozoic genera). We find that both Nymphinae and Myiodactylinae (if Dactylomyius is a member) might have existed by the mid-Cretaceous, consistent with Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015) who believed that these groups likely diverged during “the Middle Jurassic or Early Cretaceous at the latest” (p. 478). The Early Cretaceous Nymphidae are more diverse than those of the Jurassic.

Taxonomic remarks

Sialium minor differs from the type species Sialium sipylus (known only from a hind wing) and S. sinicus by the following hind wing morphology: RP1 has few dichotomous branches distally [posterior trace of RP1 is pectinately forked in these two species]; the intramedian space is slightly dilated towards the origin of MP1 as MP distad MP1 is slightly arched [MA and MP are nearly parallel]; and CuA is gradually bent to the margin [nearly parallel to the margin from most part]. The venation of S. minor is most similar by these and other character states similar to that of Spilonymphes major from the same locality. The configuration of the hind wing intramedian space shared by these two species is especially important as it does not occur in other genera of Nymphidae. This may be considered a synapomorphy, a diagnostic trait grouping them together. Here, we transfer Sialium minor to this genus: Spilonymphes minor new combination. Both species occur in the Yixian Formation of China and have similar forewing colour patterns.

Mesonymphes sibirica Ponomarenko does not belong to the genus Mesonymphes. Examination of the holotype shows that the drawing of the hind wing (Ponomarenko Reference Ponomarenko1992, fig. 2b) is in part incorrect and that its venation is actually most similar to that of the genus Nymphites. There is a single row of linked crossveins between the branches of MP and CuA in both the forewings and hind wings, similar to the condition seen in N. bimaculatus (Shi et al. Reference Shi, Makarkin, Yang, Archibald and Ren2013, fig. 6). This row of crossveins is not present in Mesonymphes (i.e., M. hageni and M. rohdendorfi Panfilov). Mesonymphes sibirica is transferred here to Nymphites: Nymphites sibiricus (Ponomarenko, Reference Ponomarenko1992) new combination.

Mesonymphes apicalis Ponomarenko also does not belong to Mesonymphes. This species is represented by a distal fragment of a wing, which was interpreted by Ponomarenko (Reference Ponomarenko1992) as a hind wing. The proximal branches of RP in this wing are strongly convergent towards the outer wing margin, which is not characteristic of any known genera of Nymphidae, and so it may not belong to this family. A more complete wing is required to resolve its position.

Menon et al. (Reference Menon, Martins-Neto and Martill2005), Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Winterton and Ren2015), and Myskowiak et al. (Reference Myskowiak, Huang, Azar, Cai, Garrouste and Nel2016) considered Araripenymphes Menon, Martins-Neto, and Martill to belong to the Nymphidae (one species: A. seldeni Menon, Martins-Neto, and Martill from the late Aptian Crato Formation). However, this unusual genus is most similar to Cratosmylus Myskowiak, Escuillié, and Nel, also from the Crato Formation, for which the monotypic subfamily Cratosmylinae was erected within the Osmylidae by Myskowiak et al. (Reference Myskowiak, Escuillié and Nel2015). Makarkin et al. (Reference Makarkin, Heads and Wedmann2017) suggested that these two genera form the family Cratosmylidae, closely related to Nymphidae and together with the Cretaceous Babinskaiidae form the epifamily Nymphidoidae (see Makarkin et al. Reference Makarkin, Wedmann and Heads2018, fig. 16). Araripenymphes strongly differs from the genera of Nymphidae by the origin of RP being distant from the wing base, the presence of many presectoral crossveins in the forewing, and the very short CuA in the hind wing.

Biogeography

The distribution of Nymphidae in the past was much wider than today. Their fossils have been found across Asia and Europe in the Jurassic; in Asia, Europe, and South America in the Cretaceous; and in Europe and North America in the Eocene (Fig. 4).

Today, they are restricted to Australia, north through New Guinea and possibly, but doubtfully, the Philippines (see Introduction). All records outside of Australia are of species of the Myiodactylinae (Fig. 5) (New Reference New1985, Reference New1988). The Nymphinae is restricted to Australia, where it is widespread, mostly but not exclusively in eastern coastal regions from Queensland south to Tasmania (New Reference New1982a, Reference New1985, Reference New1986a, Reference New1988; Oswald Reference Oswald1997, Reference Oswald1998; Global Biodiversity Information Facility 2019).

Fig. 5. Present-day distribution from data of New (Reference New1982a, Reference New1985, Reference New1986a, Reference New1988), Oswald (Reference Oswald1997, Reference Oswald1998), and Global Biodiversity Information Facility (2019). A, Myiodactylinae; B, Nymphinae. The reported occurrence of Myiodactylus at Mindanao, the Philippines, is doubtful (see New Reference New1982a).

The Nymphidae – more specifically the Nymphinae – is not the only insect group found in the Okanagan Highlands that is restricted to the Australian region today. These include the parasitoid Peradeniidae (Hymenoptera) found in southeastern Australia and Tasmania (Masner Reference Masner, Goulet and Huber1993); the ant subfamily Myrmeciinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) found in Australia, New Caledonia, and introduced in New Zealand (summary: Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Cover and Moreau2006); and termites of the family Mastotermitidae (Isoptera) that range in northern Australia and southern New Guinea (probably recently introduced) (Šobotník and Dahlsjö Reference Šobotník and Dahlsjö2017).

Other Okanagan Highlands insects today range in the Australian region, are restricted in other places, and are scattered worldwide: parasitoid wasps of the family Monomachidae, rare in Australia and tropical regions of the New World (Masner Reference Masner, Goulet and Huber1993); an undescribed species of Megymenum Guérin-Menéville (Hemiptera: Dinidoridae) distributed in the Australian and Oriental regions (Kocorek and Ghate Reference Kocorek and Ghate2012), and green lacewings of the subfamily Nothochrysinae (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae), which mostly inhabit Mediterranean and semi-Mediterranean climates around the world, including portions of southern Australia (Archibald and Mathewes Reference Archibald and Mathewes2000; Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Bossert, Greenwood and Farrell2010, Reference Archibald, Johnson, Mathewes and Greenwood2011b, Reference Archibald, Makarkin, Greenwood and Gunnell2014a, Reference Archibald, Morse, Greenwood and Mathewes2014b, Reference Archibald, Rasnitsyn, Brothers and Mathewes2018).

Although these insects inhabit climates with a wide range of mean annual temperatures, from cooler mid-latitudes to hot low latitudes, all tend to share milder winters. This is also modelled for the Okanagan Highlands, where there appears to have been no frost days even in its coldest months, despite mostly microthermal mean annual temperatures (e.g., Archibald and Farrell Reference Archibald and Farrell2003; Archibald et al. 2010; Reference Archibald, Morse, Greenwood and Mathewes2014b). The modern range of Nymphinae, extending from the tropics of north Australia to the cool temperate climate of Tasmania, similarly shares milder winters.

Other insects found in the Okanagan Highlands that are not found in Australia today also show a similar pattern of occurrences in regions of mild winters throughout the Cenozoic to the present. For example, the single extant species of Eomeropidae (Mecoptera) inhabits the mid-latitude coastal Valdivian forest of Chile, with temperate but mild winters (Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Rasnitsyn and Akhmetiev2005), and Pachymerina (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae), which are found in frost-free regions of the New and Old World where the palms that they feed upon grow (Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Morse, Greenwood and Mathewes2014b).

Eocene climates were globally equable, with frost-intolerant insects, vertebrates, and plants extending their ranges into high latitudes, such as palms (Arecaceae) and Crocodilia in temperate climates north to the Arctic Ocean (summaries: Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Bossert, Greenwood and Farrell2010, Reference Archibald, Morse, Greenwood and Mathewes2014b). The post-Eocene shift in global climate regime may then have restricted both thermophilic and cold-intolerant organisms to low latitudes for differing reasons: thermophilic taxa because of extra-tropical decrease in the mean annual temperatures and the cold-intolerant taxa by extra-tropical decrease in the coldest month mean temperatures.

This would have ended the mixed tropical/temperate communities of the Okanagan Highlands, for example, forests with spruce and palms; tropical cockroaches (Blattodea: Blaberidae: Diplopterinae) and aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae), extirpating cold-intolerant taxa (heat-requiring taxa would have never been present in these mostly upper microthermal climates) (Archibald and Farrell Reference Archibald and Farrell2003; Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Bossert, Greenwood and Farrell2010). Only Okanagan Highlands insects that could adapt to colder winters would have been able to persist there and in other extra-tropical regions where later Cenozoic broadened temperature seasonality lowered winter temperatures, for example, aphids, Siricidae (Hymenoptera), and Raphidioptera (Archibald and Mathewes Reference Archibald and Mathewes2000; Archibald and Rasnitsyn Reference Archibald and Rasnitsyn2015; Makarkin et al. Reference Makarkin, Archibald and Jepson2019); those that could not would have had their ranges moved or reduced to regions of the world without harsh winters, or would have gone extinct. Even cooler southern regions of modern Australia do not experience the extremes of winter cold common throughout the Northern Hemisphere in similar extra-tropical latitudes (Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Bossert, Greenwood and Farrell2010, fig. 1). This expansion of extra-tropical temperature seasonality (particularly Northern Hemisphere) and associated change in insect community composition since the post-Eocene global climatic downturn could, for example, in part explain the overturn in dominance within green lacewings from the Nothochrysinae to the Chrysopinae since the Eocene (Makarkin and Archibald Reference Makarkin and Archibald2013; Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Makarkin, Greenwood and Gunnell2014a).

If this model is correct, then the Nymphinae (and, more broadly, the Nymphidae) may persist in the Australian region by its possession of the key climatic similarity with the Ypresian Okanagan Highlands of mild winters independent of the mean annual temperature. Its absence in similar climates around the world (where, e.g., Nothochrysinae inhabit today) may be due to regional extirpations resulting from historical contingencies.

Acknowledgements

We thank James Haggart and Michelle Coyne (GSC) for accessioning the specimen into its type collection and Warren Wulff (librarian at the GSC) for assisting in literature search concerning early collecting at Falkland. We thank Marlow Pellatt (Parks Canada) for providing permission to use the microscope with digital camera in his laboratory; Alexander V. Khramov (PIN) for photographs of some Mesozoic Nymphidae from the PIN collections. S.B.A. thanks Rolf Mathewes (Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada) for facilitating research, including financial assistance. S.B.A. is also grateful for the fieldwork funding provided by a Putnam Expeditionary Grant through the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University (Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America).