Introduction

The moth family Gelechiidae (Lepidoptera) encompasses all feeding strategies known for Lepidoptera except exposed feeding and fungivory. These include scavenging, insect predating, lichen feeding, gall forming, leaf mining, seed mining, leaf tying, leaf rolling, stem boring, internal fruit feeding, flower boring, and case making (Karsholt et al. Reference Karsholt, Mutanen, Lee and Kaila2013). The family includes more than 4600 described species worldwide (Hodges Reference Hodges1998), with about 630 species in the Nearctic Region (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Hodges and Brown2009). Most are monophagous on a plant species or genus, with hosts ranging across flowering plants, conifers, mosses, ferns, and lichens (Karsholt et al. Reference Karsholt, Mutanen, Lee and Kaila2013). Such specificity has yielded agriculturally important pests, like the potato tuberworm (Symmetrischema tangolias (Gyen) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae)) (Keasar et al. Reference Keasar, Kalish, Becher and Steinberg2005) and the tomato leafminer (Tuta absoluta Meyrick (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae)) (Shaltiel-Harpaz et al. Reference Shaltiel-Harpaz, Gerling and Graph2016), as well as promising biological control agents against invasive weeds (Story et al. Reference Story, Boggs, Good, Harris and Nowierski1991). The life history of most, however, is poorly known. Evolutionarily, feeding strategies of gelechiids are highly labile, with multiple feeding strategies occurring within clades (Karsholt et al. Reference Karsholt, Mutanen, Lee and Kaila2013). This combination of high host specificity and evolutionarily labile feeding strategy is particularly interesting from an evolutionary point of view: it allows for strong adaptation to host plants over relatively short spans of evolutionary time. In their review of research on plant–herbivore interactions, Karban and Agrawal (Reference Karban and Agrawal2002) used the term “herbivore offense” to describe the derived modes used by herbivores to exploit their hosts and argued for further consideration of the exploitative mechanisms of herbivores to understand more fully the coevolution of herbivores and host plants. We suspect that the Gelechiidae will prove to be an excellent group of insects to study in this regard.

Within the Gelechiidae, shifts in feeding strategy can occur more frequently than shifts in host plant lineage. All 51 species in the New World genus Symmetrischema Povolný are known to use hosts only in the family Solanaceae (Busck Reference Busck1903; Povolný Reference Povolný1967; Des Vignes Reference Des Vignes1979; Blanchard and Knudson Reference Blanchard and Knudson1982; Powell and Povolný Reference Powell and Povolný2001). They do so, however, in a variety of ways, including gall making, bud feeding, fruit feeding, and stem boring. Symmetrischema kendallorum feeds and pupates in galls on the upper stems of Physalis virginiana Miller (Solanaceae) (Blanchard and Knudson Reference Blanchard and Knudson1982). The agricultural pest S tangolias is a stem borer of plants in the genus Solanum Linnaeus (Solanaceae), including agriculturally important potatoes and tomatoes. In S. tangolias the mature larva exits the stem and pupates in the soil or plant debris (Busck Reference Busck1931; Powell and Povolný Reference Powell and Povolný2001). The only species in the genus previously known to use multiple feeding strategies is Symmetrischema capsicum (Bradley and Povolný), which feeds and pupates in the fruit when using Physalis Linnaeus as a host, but feeds on buds and pupates in soil when using Capsicum as a host (Des Vignes Reference Des Vignes1979). Thus, different feeding and pupating strategies may evolve to take advantage of the different ecological opportunities present on different hosts and their environments.

The species Symmetrischema lavernella (Chambers) is widespread in the United States of America, with collections from the District of Columbia to Texas, and as far north as Michigan and Maine (Brower Reference Brower1984). Previous observers record it as a fruit feeder on the plant genus Physalis, including three specimens from P. hederifolia Gray and one from Physalis viscosa Linnaeus (Povolný Reference Povolný1967). In northern Virginia, we observed it regularly on two host plants: P. heterophylla Nees and P. longifolia var. subglabrata (Mackenzie and Bush) Cronquist. On both host plant species, we found larvae engaged in two feeding strategies: feeding on and then pupating inside a single developing fruit (fruitworm) or feeding on and then pupating inside a single unopened floral bud (budworm). Both strategies were in use simultaneously on the same plants and adjacent floral structures sometimes contained moth larvae using different feeding strategies. This work represents an attempt to understand the basic natural history underlying the use of these two feeding strategies by the same species of insect.

We set forth five goals in our study of S. lavernella: through observations, we (1) characterise oviposition pattern and subsequent development in each feeding strategy, (2) document the broad pattern of feeding strategy across the flowering season, and (3) survey the natural enemies of S. lavernella. Through manipulations, we (4) examine the underlying mechanism that determines which mode is used and (5) determine if larval occupancy and feeding under the fruitworm strategy initiates and maintains fruit induction in the absence of pollination.

Methods

Taxonomy and voucher specimens

The genus Symmetrischema, erected by Povolný (Reference Povolný1967) based on genital characters, originally included 13 species. As currently classified, the genus includes 51 species. Symmetrischema lavernella was originally described by Chambers (Reference Chambers1874) in the genus Gelechia Hübner based on a female specimen from Texas. Busck (Reference Busck1903) synonymised the taxon Gelechia physalivorella (Chambers) as a junior synonym of Gnorimoschema lavernella. Later Povolný (Reference Povolný1967) transferred the species from Gnorimoschema Busck to his newly described genus, Symmetrischema, where it remains a valid combination. Voucher specimens from this study are deposited in the Hasbrouck Insect Collection at Arizona State University (Tempe, Arizona, United States of America).

Field site

All field and laboratory work was carried out between 2009 and 2014 at Blandy Experimental Farm (Virginia, United States of America, 39.06°N 78.06°W), an ecological field station of the University of Virginia. Observations were made on wild plants of both Physalis longifolia and P. heterophylla, but only P. heterophylla was used for manipulative experiments reported here. The basic natural history of the moth species was inferred through field observations and laboratory dissections of floral buds and infected fruit.

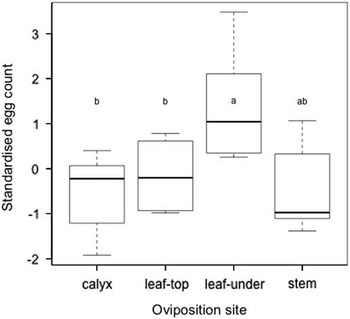

Oviposition preference

Oviposition preference was determined by counting all eggs deposited on 12 potted plants exposed to an active wild population of S. lavernella during June and July 2014. Eggs were counted once for each plant. Oviposition sites were classified as top of leaf, bottom of leaf, calyx, or stem (including pedicel, petiole, and main stem).

Seasonal pattern of feeding strategy

We monitored two populations of P. heterophylla weekly at Blandy Experimental Farm from 1 June through 30 July 2012 for the appearance of fruitworms and budworms. One of these was a natural population and occurred in an early successional field. The second population comprised 63 potted plants propagated from vegetative material dug from the same population the previous year and placed in the field near an existing population of P. longifolia. All infections were tagged when observed in the field and returned to the laboratory after pupation to observe emergence.

Development and role of bud size in the developmental pathway

The timing of developmental milestones and the role of bud size in determining feeding strategies were determined through greenhouse manipulations. Twenty-one P. heterophylla plants propagated from wild cuttings were potted and maintained in a 22 °C greenhouse at Blandy Experimental Farm and caged from insects. An adult S. lavernella population was maintained in a separate cage with additional P. heterophylla plants. Weekly, 10–20 adult moths were captured in the rearing cage and placed for two days in a smaller cage with a cut branch from a P. heterophylla plant. The cut branch was then removed and checked for eggs. Eggs were transferred to leaves in a moist petri plate and monitored daily for hatching. As groups of first instars became available, they were transferred to a stem of a potted P. heterophylla plant. The stem was isolated from the rest of the plant using Tanglefoot® (The Tanglefoot Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan, United States of America), which forms a sticky, impenetrable barrier to crawling insects. Before the introduction of caterpillars, all flower buds and open flowers were noted. Open flowers were marked with hanging paper tags; when large enough, flower buds were also tagged. Because flowers are widely spaced and open acropetally along the stem, bud identifications could be maintained even when they were too small to tag. Twice as many caterpillars as measurable buds were introduced to each stem, and they were spread along the entirety of the target stem so that each bud would have larvae placed near it. The number of available structures per stem ranged from two to nine and all caterpillars given to a particular stem were introduced on the same day.

Pollination requirements of Physalis heterophylla

Understanding the role of S. lavernella in fruit initiation necessitates understanding the pollination requirements of the host plant. A total of 282 flowers on seven plants transplanted from the field were subjected to one of three pollination treatments in a greenhouse: outcross pollen, self pollen, and no pollen. Outcross pollen derived from a randomly chosen sire among study plants and was applied with the head of an insect pin. Self pollen was collected from another flower on the same plant and applied with an insect pin. In the no pollen treatment, the stigma was touched with the head of an insect pin but no pollen was applied.

Natural enemies

Natural enemies were observed both opportunistically and in one set of systematic observations. Over several years, pupating/pupated S. lavernella were opportunistically collected from both buds and fruits of wild plants and transferred to falcon tubes in the laboratory until emergence. In 2014, 132 P. heterophylla plants in three patches were examined weekly from the last week of June until the last week of August. Infected fruits were tagged and monitored each week, with pupating S. lavernella returned to the laboratory to monitor emergence. When possible, cause of death was assigned. The larger frugivorous caterpillar Heliothis subflexa (Guenée) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) was considered to be the cause of death when large caterpillar frass accompanied a destroyed fruit previously occupied by S. lavernella.

Interactions with Heliothis subflexa

Heliothis subflexa is a common, much larger, externally feeding frugivore that consumes multiple fruits during its development. At the field site, we often found evidence of recent or active H. subflexa feeding on fruits that showed evidence (i.e., cocoon threads or an entrance hole through the ovary wall) of prior S. lavernella colonisation. We examined the fruit preference of fifth instar caterpillars (1.7–2.5 cm) of H. subflexa in the laboratory by presenting them with a pair of mostly to fully developed P. heterophylla fruits, one with and one without S. lavernella inside. Fruit sizes were matched as closely as possible for each trial and presented 2 cm apart. Heliothis subflexa caterpillars were field collected before use and reared on commercial tomatillo fruits (Physalis species) until the fifth instar, then starved for 12 hours before testing. Tests were done in a petri dish and all H. subflexa caterpillars and P. heterophylla fruits were used only once. A total of 43 trials were carried out. A choice was recorded when H. subflexa began consuming one of the fruits. If a choice was not made within 30 minutes, the trial was terminated without a recorded outcome.

Statistics

All analyses were carried out in R 3.2.2 (R Development Core Team 2013). For all comparative analyses between fruitworms and budworms, only branches in which both fruitworms and budworms were produced were used in the analysis.

Relationship of floral bud size to feeding strategy

A generalised linear effects model using glmer in the lme4 package (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) was used to construct a logistic regression model with developmental pathway (budworm or fruitworm) as the dependent variable, bud length as the predictor variable and plant identification as a random factor. A model including branch within plant failed to converge, so we present an analysis in which data are pooled within plant. Data from flowers open at the time of caterpillar introduction were excluded from this analysis; all open flowers (n=32) that were colonised produced fruitworms. Buds too small to measure at the time of caterpillar introduction were assigned a length of 0.1 mm.

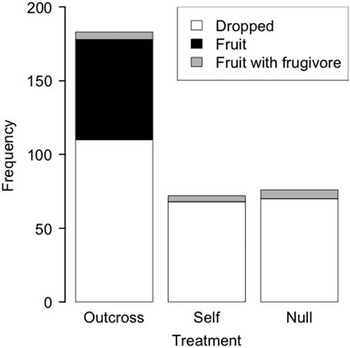

The effect of pollination type on fruit development

Each of the three treatments was replicated at least six times (depending on flower availability) on each of the seven plants. A g-test was carried out for each experimental plant and the log likelihood ratio statistic (G) was pooled across tests and compared with the pooled degrees of freedom to test for overall significance.

Results

Oviposition and development based on field observations

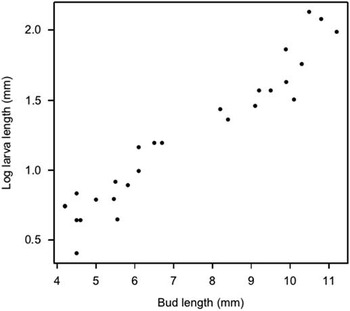

Adult females oviposited single eggs towards the top of the plant on small flower buds, pedicels, stems, and upper leaves, most commonly on the underside of upper leaves (Fig. 1). On several occasions first instars (0.5–0.7 mm) were observed under the microscope crawling among tightly clustered buds and feeding on trichomes. Larger S. lavernella caterpillars were seldom seen in a free-living state, but could readily be found feeding within one of two substrates where they consumed distinct floral resources. We refer to these feeding strategies as “fruitworm” and “budworm” (Figs. 2–3), both of which routinely occur on the same plants at the same time. Budworms enter floral buds then consume the immature ovary, anthers, and some petal tissue before fastening the calyx lobes with cocoon threads and pupating inside the consumed bud. Fruitworms, in contrast, enter a bud or open flower, chew through the ovary wall near the connecting point of the style, descend the ovary and feed on developing ovules. The entrance hole through the ovary wall seals quickly, but leaves a red scar that reveals its occupancy. Growth of the caterpillar inside the ovary strongly parallels growth of the fruit (P<0.001, r 2=0.86, Fig. 4). Ovules were the only part of the ovary that we observed being consumed by the fruitworm during development, and toward the end of larval feeding most or all of the ovules were destroyed without developing into seeds. At the end of feeding, the caterpillar chews a narrow round exit hole near the bottom of the ovary and often another hole through the inflated calyx then returns to the hollow fruit to pupate, with the cocoon threads plugging the exit hole. The emerging adult fruitworm exits through the hole it had chewed as a caterpillar.

Fig. 1 Comparison of the number of eggs deposited on different plant structures. Above=upper leaf surface. Below=lower leaf surface. Stem includes pedicel, petiole, and branch. Data standardised to control for different numbers of eggs on plants in the field.

Fig. 2 Life history of Symmetrichema lavernella as a fruitworm. Upper left: free-living, 0.5-mm larva among young flower buds. Upper right: red mark in developing fruit where larva entered the ovary. Centre left: young fruitworm consuming ovules. Centre right: late fruitworm just before pupation. Lower left: exit hole prepared before pupation. Pupa inside fruit, with cocoon threads covering hole. Lower right: adult moth perched on leaf.

Fig. 3 Distinct stages of Symmetrichema lavernella developing as a budworm. Upper left: infected bud. Not always discoloured but usually with attenuated bud tip. Upper right: young budworm, having damaged the style. Lower left: late budworm, after consuming anthers, ovary, and style. Lower right: budworm pupa.

Fig. 4 Growth of fruitworm inside the ovary compared with growth of the fruit. P<0.001, adjusted r 2=0.85.

Multiple early instars were occasionally found in the same bud or ovary, but usually only one caterpillar was alive at inspection and multiple caterpillars were never observed reaching maturity in the same structure. Direct antagonism between caterpillars was not observed and the cause of death to subsequent caterpillars entering a structure is unknown.

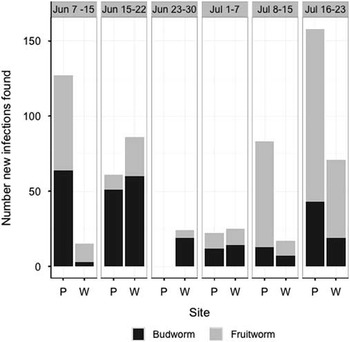

Seasonal pattern of feeding strategy

Physalis heterophylla produced its first flowers in field plots in early June, and S. lavernella colonised many of the first flowers. We observed 238 infections on 23 plants in the wild population and 452 infections on the 63 potted plants placed in the field. Early infections were primarily by fruitworms in the wild population but balanced between fruitworms and budworms among the potted plants (Fig. 5). By the second week, new infections were mainly by budworms at both sites. A second round of infections began in early-mid July, presumably representing a second generation of moths. The first infections in the second generation were predominately fruitworms but a shift to colonisation mainly by budworms was not observed in the second generation. Systematic observations were not continued beyond the second generation, but Physalis continues flowering into September at the field site and later infections were noted, indicating at least three generations.

Fig. 5 Number of new infections of each feeding strategy found per week at two field sites. P, potted plant population; W, wild population.

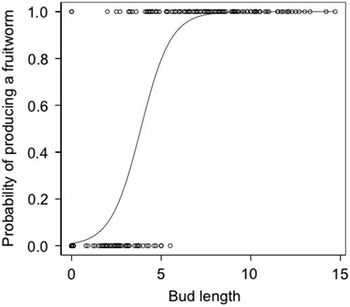

Determination of feeding strategy

In the greenhouse, a total of 364 buds and open flowers were measured and tracked, 242 of which were colonised by S. lavernella. Caterpillars colonised flower buds across a wide range of sizes (<1–15 mm, and open flowers). Bud size was a very strong predictor of feeding strategy (P<0.001), with buds <4.05 mm at the time of caterpillar introduction typically producing budworms and buds >4.05 mm, as well as open flowers, typically producing fruitworms (Fig. 6). Fruitworms usually pupated successfully (116/180=64.4%) and 46.7% reached adulthood. Budworm success was not estimated, as budworm infections are difficult to recognise in their early stages and thus their early mortality could not be incorporated into survival estimates.

Fig. 6 Logistic regression showing the probability of the strategy being a fruitworm based on the length of the floral bud presented to a first instar.

Pollination requirements of Physalis heterophylla and implications for fruit induction by larval feeding

Of the 282 open flowers receiving pollination treatments, five were discarded because of wilted branches. Of the remaining flowers, 83 set fruit but 15 of those were infected by fruitworms of S. lavernella that were inadvertently introduced to the greenhouse. Of the 68 fruits not containing a fruitworm, all arose from the outcross pollen treatment (68/124) and none from the self (0/70) or the null (0/68) treatments, indicating a need for pollination with outcross pollen for fruit induction (Pooled G=125.4, df=14, P<0.01). Every tested plant produced fruit from cross pollinations. Among the 15 fruits containing fruitworms, six occurred in null treatments and four occurred in self treatments (Fig. 7). Because these treatments did not produce fruits in the absence of caterpillars, fruit induction could only arise from caterpillar activity or from outcross pollination by the adult moths. The presence of adult moths is not required for fruit induction when the ovary is occupied by S. lavernella, however (see Determination of feeding strategy above), thus indicating that the presence of the larva in the ovary is the likely cause of the ovary developing into a fruit rather than aborting.

Fig. 7 Fruits produced from different pollination treatments. Infections by fruitworms were inadvertent to the pollination treatments.

Natural enemies

Across all field collections of budworms and fruitworms, three parasitoid species have been reared from S. lavernella: an ichneumonid wasp (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) in the subfamily Cryptinae (n=5), a braconid wasp (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) in the genus Bracon Fabricius (n=31), and a chalcid wasp (Hymenoptera: Chalcididae) in the genus Conura Spinola (n=9). In a structured field collection during 2012, 10 of 97 S. lavernella pupae brought to the laboratory from the field were found to have parasitoids (six Bracon and four Cryptinae). Cryptinae and Bracon specimens were reared from both fruitworms and budworms, while Conura was only reared from budworms. Cryptinae and Conura killed the moth during pupation and emerged from its pupal case while Bracon killed S. lavernella as a late instar and created a pupal case inside the floral structure. Evidence of fruit consumption by the externally feeding frugivorous caterpillar H. subflexa was sporadically found along with remaining pieces of S. lavernella (e.g., cocoon threads or pupal cases), indicating that H. subflexa could be an important natural enemy.

In laboratory choice trials, H. subflexa first consumed the fruit containing S. lavernella in 17 of the 26 trials in which a choice was recorded (P=0.11, χ2 test). In all trials in which H. subflexa chose an infected fruit, it consumed the entire fruit, including S. lavernella. The larger caterpillar was observed directly attacking and consuming S. lavernella (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8 Larger frugivore Heliothis subflexa feeding on Symmetrischema lavernella that has just exited the fruit.

Of 132 plants monitored in three patches in 2014, 20 plants were uninfected but the remaining 112 contained a total of 437 fruitworms. Of those, 19.7% survived to adulthood. The leading attributable causes of failure were fruit/larval consumption by the caterpillar H. subflexa (31.3%), fruits dropping off the plant (10%), and frugivory by unknown vertebrates and invertebrates (9.6%). Failure could not be attributed to a cause in 42.6% of cases. In such cases, fruits were often shrivelled and dried out but it was unclear whether these cases were due to plant processes or environmental desiccation following fruit damage by unknown sources. Only two of these 437 fruitworms yielded a parasitoid. A total of 105 budworm infections were observed during fruitworm monitoring but they could not be compared with fruitworm survival given that they could not be recognised during the early stages of infection.

Discussion

Three aspects of the life history of S. lavernella are noteworthy: that the presence inside the ovary of an unpollinated flower causes the flower to develop into a fruit, that it consumes different food sources and develops in a different plant structure depending on the size of the bud it enters, and that one of the main sources of mortality is a specialist frugivore that not only competes for fruits but consumes it directly.

Colonisation of the ovary by S. lavernella causes fruit formation in the absence of pollination. This is inferred by the results of two experiments, neither of which is sufficient alone. The pollination experiment shows that the plants at the study site do not develop fruit in the absence of pollination (except when infected by S. lavernella). Because these plants were accessed by adult moths for oviposition, it cannot be ruled out that adult moths pollinated the flowers. This seems unlikely because the caterpillars typically colonise the ovaries before the flowers open and because the flowers close at night, when the adult moths are active. Even if adult moths were active in flowers, the manipulative greenhouse experiment in which caterpillars were introduced to plants in the absence of adult moths (or other insects) shows that fruit development occurs following colonisation by a S. lavernella caterpillar in the absence of potential pollinators. Thus, the fruitworm strategy is available regardless of pollinators in the environment. How colonisation leads to fruit formation is unknown. There are very few examples in the literature of flowers producing fruit as a result of insect activity, aside from actual insect pollination. The gelechiid moth Frumenta nundinella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) also causes fruit formation when it colonises Solanum carolinense Linnaeus flowers (Solomon Reference Solomon1980). In that plant species, as well as some fig species (Ficus Linnaeus, Moraceae) (Galil et al. Reference Galil, Dulberger and Rosen1970), manual damage to the reproductive structure is sufficient to induce fruit formation. In Physalis, successful pollination leads to inflation of the calyx to several times its original volume as well as elongation of the ovary and swelling of the ovules. All of these outcomes of pollination are apparent following colonisation. Inflation of the calyx (inflated calyx syndrome) is a floral trait limited to a few genera in the Solanceae (Hu and Saedler Reference Hu and Saedler2007). In both Physalis and the closely related Withania Pauquy, cytokinins and gibberellins act as signals to the flower bud to inflate the calyx following pollination (He and Saedler Reference He and Saedler2007; Khan et al. Reference Khan, Hu and He2012). In Withania, suppression of the hormone ethylene also led to an inflated calyx (Khan et al. Reference Khan, Hu and He2012). Thus, there are various pathways that may be exploitable by a colonising insect that benefits from being in a developing fruit, but which pathway and how it is exploited are unknown. The exploitation of hormonal pathways to prevent the host plant from dropping the fruit would qualify as a particularly sophisticated form of “herbivore offense” (Karban and Agrawal Reference Karban and Agrawal2002).

Although fruitworms and budworms originate in floral buds of the same host plants, they represent dimorphic strategies that differ categorically in food source, developmental environment, and behaviour. Budworms consume the anthers, ovary, and some petal tissue; develop just under the calyx; and bind the calyx lobes together with cocoon threads to close their developmental chamber. Fruitworms, in contrast, consume ovules, develop inside a thickened, expanded and sealed ovary wall that is inside an inflated calyx, and excavate an exit hole through the fruit just before pupation. For budworms, the richest source of nutrition is likely to be the anthers, which contain immature pollen grains. Physalis is in the plant family Solanceae, which typically has pollen grains very rich in protein (Roulston et al. Reference Roulston, Cane and Buchmann2000). The nutritional content of immature pollen, such as that being consumed by budworms, is unknown, however. While the apparent food source for fruitworms is developing ovules, it is possible that fruitworms not only consume the contents of the ovules but also material flowing to the ovules through vascular connections to the rest of the plant.

Feeding variation within insect species is usually associated with differences in the availability of preferred resources. The gelechiid moth F. nundinella Zeller (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae), like S. lavernella, uses one of two different feeding substrates on the same host, S. carolinense, and also develops in a different structure – either a leaf capsule at a meristem or within a fruit (Solomon Reference Solomon1980). In F. nundinella, however, the meristem is used by the entire first generation and the fruit is used by the second generation. In S. lavernella, both developmental patterns occur simultaneously on the same plants. In this species, the proximal cause of a shift towards the predominance of budworms is likely bud availability. When plants began flowering at the study site, the strategies were equally represented in one population and fruitworm dominated in another (Fig. 5). Early in the flowering season, flowers are relatively rare. Physalis heterophylla produces flowers before P. longifolia at the study site (T.H.R., personal observation) and thus there are few flower buds available for the overwintering population of adult moths seeking oviposition sites. Once the larger buds, which will produce fruitworms, are colonised on a stem, only small buds remain and they will produce budworms. Under high infection rates, the system is expected to produce only budworms because all new buds will be colonised before they are large enough to support fruitworms. Such a situation would continue to produce only budworms until a gap between generations would allow uncolonised floral buds to reach sufficient size to support fruitworms. Later in the summer, during the second generation of S. lavernella, flower buds were more plentiful. Flower buds per plant increase as Physalis grows and the second host plant species, P. longifolia was also flowering abundantly during the second generation. Understanding the selection pressures that govern developmental strategy, however, will require an understanding of the differences in success between the two strategies and whether or not there are genetic factors influencing the choice of strategy. Given that the preferred oviposition substrate is underneath leaves, bud choice is ultimately made by wandering neonate larvae, but larval choice is constrained by the oviposition choices available on a given plant, which are influenced by prior adult female oviposition decisions.

Heliothis subflexa, a large frugivorous caterpillar that specialises on Physalis, potentially has large effects on survival of S. lavernella. Each individual consumes multiple fruits to develop and can be extremely common at both agricultural and wild sites. It is considered an important pest of commercially grown Physalis ixocarpa Brotero ex Hornemann (tomatillo) in Mexico where it can destroy over half the crop at low altitudes (Bautista-Martinez et al. Reference Bautista-Martinez, Lopez-Bautista and Madriz2015). It is also very common on wild species of Physalis (Bateman Reference Bateman2006). Defensive traits in some Physalis species, such as leaf necrosis at the site of oviposition (Petzold-Maxwell et al. Reference Petzold-Maxwell, Wong and Arellano2011) and fruit abscission following damage (Benda et al. Reference Benda, Brownie, Schal and Gould2009), may have evolved to reduce damage by major frugivores, especially H. subflexa. Because H. subflexa does not avoid fruits occupied by S. lavernella, and in laboratory situations deliberately consumed the smaller caterpillar, H. subflexa may play a strong role in regulating S. lavernella populations. In the field, 31.3% of fruitworm deaths were attributed to fruit consumption by H. subflexa. When common, H. subflexa may increase the relative advantage of the budworm strategy over the fruitworm strategy.

There are likely to be tradeoffs involved in the two feeding strategies. The fruitworm strategy appears to offer better physical protection against parasitoids, given the thickened fruit wall surrounding the developing caterpillar. Parasitism, however, was relatively rare in our system and it is possible that the escape door the fruitworm makes before pupation makes it more vulnerable to attack during the pupal stage. Furthermore, because the fruit itself is attractive to fruit consumers, the fruitworm is likely susceptible to more types of antagonism than budworms are. Because we were unable to recognise budworms early enough in development to compare survival, we cannot tell if one feeding strategy has a higher likelihood of success than the other from these data. We also do not know if one strategy is preferred over the other. The general pattern from our field study that the fruitworm strategy is more likely to occur early in a S. lavernella generation seems to suggest a preference for larger buds if they are available, but preference tests by caterpillars are required to truly test this, as the pattern could arise by other means, such as more frequent failure of budworms early in development making their choices undetectable. In the relatively similar system of S. carolinense and the gelechiid moth F. nundinella (Solomon Reference Solomon1980), there is a strong prevalence of the fruitworm form in the second generation even though the leaf substrate used by the first generation is still available; that suggests a preference of fruit over leaves in that species. It is difficult to make comparisons, however, when the options are separated in time: it is possible the leaf strategy would be better in the first generation even if fruits were available, depending on other factors, such as the natural enemies prevalent at that time. The current system seems like a robust natural system for examining tradeoffs in feeding strategy while keeping as many factors as possible constant.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Robert Kula for the identification of parasitoids and Tim Stanonik and Adriana Foster for assistance in the field. This work was partially supported by the National Science Foundation through Research Experiences for Undergraduates site grants (DBI 0755198 and DBI 1156796). The manuscript benefitted greatly from two anonymous reviewers.