Introduction

Over 150 species of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) have been introduced into new environments but a small number of tropical and subtropical species have led to pronounced effects on native ants, other arthropods, and even threatened native plants by disrupting ant-plant mutualisms (McGlynn Reference McGlynn1999). These invasive species include the Argentine ant, Linepithema humile (Mayr); the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta Buren; the tropical fire ant, Solenopsis geminata (Fabricius); the African big-headed ant, Pheidole megacephala (Fabricius); the little fire ant, Wasmannia auropunctata (Roger); and the yellow crazy ant, Anoplolepis gracilipes (Smith) (reviewed in Holway et al. Reference Holway, Lach, Suarex, Tsusui and Case2002). These ants are found outdoors in tropical, subtropical, or Mediterranean climate zones. Myrmica rubra (Linnaeus) is a Palaearctic ant species that was first found in North America in Massachusetts, United States of America in the first decade of the 20th century (Groden et al. Reference Groden, Drummond, Garnas and Francoeur2005). In Eurasia, nests consisting of several hundred workers are found in deciduous woodlands, gardens, and grasslands, usually in the soil, under woody debris, or leaf litter in (Fokhul et al. Reference Fokhul, Heinze and Poschlod2007). Like many successful invasive ant species, colonies of M. rubra are normally polygynous and polydomous. Workers prey on insects and other small invertebrates and attend aphids and other Hemiptera, from which they collect honeydew. They may also collect and disperse seeds that contain elaiosomes (Fokhul et al. Reference Fokhul, Heinze and Poschlod2007) that are rich in essential amino and fatty acids.

Myrmica rubra has now been reported in all the Canadian provinces east of Manitoba, and in at least six northeastern states and Washington State in the United States of America. Most of the reports are from within the last 10 years, suggesting that the North American populations are expanding (Wetterer and Radchenko Reference Schlick-Steiner, Steiner, Moder, Seifert, Sanetra and Dyreson2011) or that a new introduction is ecologically distinct from the century-old arrivals. It likely arrived in southwestern British Columbia, Canada at least 20 years ago but went relatively unnoticed for several years (Higgins Reference Higgins2013). North American populations have not been observed to produce flying females (Hicks Reference Hicks2012), so introductions are suspected to occur via the transport of garden products or soil, and spread occurs through colony budding. Workers can deliver a painful sting, an unusual feature among native ant species in British Columbia (Naumann et al. Reference Naumann, Preston and Ayre1999), leading to the ant being called the European fire ant (EFA) in North America. At high populations, EFA stinging can make yard and garden work difficult, cause distress for pets, and there is concern that they may be interfering with the successful nesting of some birds (Higgins Reference Higgins2013). Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Knowler, Kyobe and de la Cueva Bueno2013) estimated that the economic cost of the EFA in British Columbia could reach $100 million/year if they spread across their potential range in the province.

Although populations of the EFA in eastern and western North America are still fragmented, their tendency towards high population densities and the pugnacious nature of the workers suggests that this species could be having similar ecological effects to other invasive ants. Multi-queen, multi-nest colonies have the potential to monopolise entire habitat patches. The purpose of the research was to determine if established populations of the EFA in British Columbia are correlated with lower species richness and abundance of native ant species and other ground-dwelling and leaf litter-dwelling arthropods.

Materials and methods

Study sites

The field work was carried out during the summer of 2013 at four locations near the mouth of the Fraser River, in southwestern British Columbia. The abundance and incidence of native ant species and other leaf litter-dwelling (epigaeic) arthropods were compared in sites with the EFA versus similar control sites without established populations of these ants. A preliminary survey found that the EFA has expanded into a variety of plant communities; three of which were specifically studied here: first, a well-drained riparian zone dominated by cottonwood (Populus balsamifera subsp. trichocarpa (Torrey and Gray) Brayshaw; Salicaceae) and Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius (Linnaeus) Link; Fabaceae); second, a moister, more shaded community, dominated by red alder (Alnus rubra Bongard; Betulaceae), and two exotic blackberries, Himalayan blackberry (Rubus discolor Weihe and Nees; Rosaceae), and evergreen blackberry (Rubus laciniatus Willdenow); and third, grassy fields. All three environments are indicative of human impact but the study locations had been relatively undisturbed for over a decade.

Poplar/Scotch broom sites with the EFA were identified at McDonald Beach Park on Sea Island and Fraser River Park in Vancouver; infested alder/blackberry sites were located within the Sea Island Conservation Area and at Fraser River Park; infested grassy areas were all within the Sea Island Conservation Area. Matched EFA-free control sites were located on nearby Iona Island and Pacific Spirit Park (Vancouver) (cottonwood/Scotch broom); and the Sea Island Conservation Area (grass and alder/blackberry). The EFA-infested sites were chosen to be as similar to the un-infested sites as possible, often being separated only by an arm of a river or a canal. All sites were within 5 km. The presence or absence of the EFA was confirmed by hand collecting and setting out apple slices as baits, to which the EFA rapidly recruit (Higgins Reference Higgins2013).

Sampling

Sampling was accomplished by pitfall trapping within each of six study zones, i.e., EFA-infested and un-infested areas in each of the three vegetation types. Other sampling methods were tested in preliminary work but were rejected; hand collecting makes quantification difficult; bait trapping (with apple slices and oily tuna) captured only a subset of the ant species found in the pitfall traps and is biased towards those species that that are active during the baiting period or best able to exploit and defend a bait. Mini-Winkler extractions of soil and leaf litter likewise collected only a subset of the local ant fauna, and the red alder blackberry zone had little leaf litter in some locations. Pitfall trapping is not the ideal collecting method for all types of epigaeic arthropods, such as Collembola and Diplura, however we include this data in order to make a preliminary estimate of the effect of the EFA on non-ant arthropod species.

Once per month, in June, July, and August, 20 Nordlander pitfall traps were placed within each of the six study zones. The traps were located a minimum of 10 m apart and at least 10 m from the edge of a vegetation zone. Each trap consisted of a lidded, 237 mL, plastic cup, with ~25 (6 mm diameter) holes punched around the upper circumference, just below the rim (Higgins and Lindgren Reference Higgins and Lindgren2012). The cups were buried so as to leave the holes at ground level, giving access to epigaeic arthropods. A small amount of litter was placed onto the lids to make them less visible to vertebrates. Each trap contained ~80 mL of a preservative solution of 25% propylene glycol: 75% water. The traps were left undisturbed for one week and then the contents of each individual trap collected, labelled, and stored for analysis. Any traps that were disturbed by mammals, birds, or people were excluded from the analysis. All ants in each trap were counted and identified to species using the keys of Wilson (Reference Wetterer and Radchenko1955); Naumann et al. (Reference Naumann, Preston and Ayre1999); Fisher and Cover (Reference Fisher and Cover2007), and an unpublished key to the Myrmica by A. Francoeur (Centre de données sur la biodiversité du Québec, Chicoutimi, Québec, Canada). Non-ant arthropods were identified to order or family and categorised into morphospecies.

Data analyses

Incidence of different ant species

While total trap captures were tallied by species, the areas with the EFA and those without were compared in terms of the number of traps containing at least one individual of a given species, i.e., incidence at the trap level. Data for the three sampling periods were consistent and were pooled for each vegetative area and EFA status.

Non-ant species

The pooled numbers of captured individuals of each species were determined for each plant community and EFA status over all three sampling periods, i.e., each value represented the summed data from ~60 traps in each of the three plant communities for both EFA present and absent sites. Morphospecies were grouped by order or family. Numbers of individuals of each taxon collected in areas with and without EFA were compared with χ2 tests, correcting for multiple comparisons with the sequential Bonferroni technique (Rice Reference Rice1989; Human and Gordon Reference Human and Gordon1997). Rarely captured species (those with a total of five individuals or less) were not reported. In the comparisons of taxa, two sums were considered to be different if the P value derived from the χ2 test was <0.0012, i.e., (α/n) 0.05/42.

Biodiversity indexes

Smoothed (100 randomisations) species accumulation curves were generated using EstimateS (9.1.0) to assess sampling adequacy (Longino Reference Longino2000; Colwell Reference Colwell2013). Fisher’s α, Simpson’s Inverse, and Shannon’s biodiversity-indexes were calculated using EstimateS (9.1.0) software (Colwell Reference Colwell2013) and these were compared between areas with the EFA and EFA-free areas in all three plant communities. All species, including rarely captured species, were included. In order to determine if the presence of the EFA affected the biodiversity of arthropods other than ants, the same three biodiversity indexes were also calculated with the ant data excluded.

Results

Ant species

Fourteen ant species were observed in the course of the study (Table 1). This level of species richness is typical for those areas of southwestern British Columbia that do not have a closed canopy of coniferous forest, including disturbed sites (Naumann et al. Reference Naumann, Preston and Ayre1999). One of the 14 species, Formica obscuripes Forel, was hand collected at one location in the cottonwood/Scotch broom community but was not captured in a pitfall trap and is not included in any analyses. Eleven ant species were found in the pitfall traps in the cottonwood/Scotch broom community when the EFA were absent but only two of those species were collected where EFA was present, and then only in a small number of traps (Fig. 1). In the grassy areas, three ant species were collected in the uninfested areas. The two most widely distributed were congenerics of the EFA, M. incompleta Provancher and M. specioides Bondroit. The latter species is exotic in British Columbia and it is not known how long it has been present. It does not show the characteristics of an invasive ant although there have been complaints of people being stung on Vancouver Island, British Columbia (personal observation). No individuals of M. incompleta or M. specioides were collected in grassy areas where M. rubra was present. Only a small number of individual ants (from three species) were collected in the red alder/blackberry zone when the EFA was absent but these species were no longer captured where the invasive species was established (Fig. 1). The EFA was captured in every pitfall trap placed in the infested areas of all three plant zones, often thousands per trap. The EFA represented more than 99.99% of the total ant fauna caught in the infested areas, and the numbers of the EFA captured in the cottonwood/Scotch broom zone were just over 100 times the total number of all ants collected in the corresponding un-infested zone (52 893 versus 506); ~10 times in the grassy areas (71 023 versus 6783), and over 1300 times in the red alder/blackberry zone (23 151 versus 17).

Fig. 1 Ant species incidence, measured as the number of pitfall traps collecting at least one individual of a given species.

Table 1 Total numbers of individuals of each ant species captured in pitfall traps within study sites near the mouth of the Fraser River, southwestern British Columbia, Canada.

Note: Tetramorium species E has usually been referred to as T. caespitum (Linnaeus) but Schlick-Steiner et al. (Reference Schlick-Steiner, Steiner, Moder, Seifert, Sanetra and Dyreson2006) determined that the name had been applied to a number of similar species. Formica obscuripes was hand collected in a cottonwood/Scotch broom community, not caught in a pitfall trap.

A small number of traps were disturbed by being pulled from the ground by dogs, a coyote, and what was probably a beaver. These were excluded from the analyses.

Biodiversity of all captured species and the non-ant arthropods

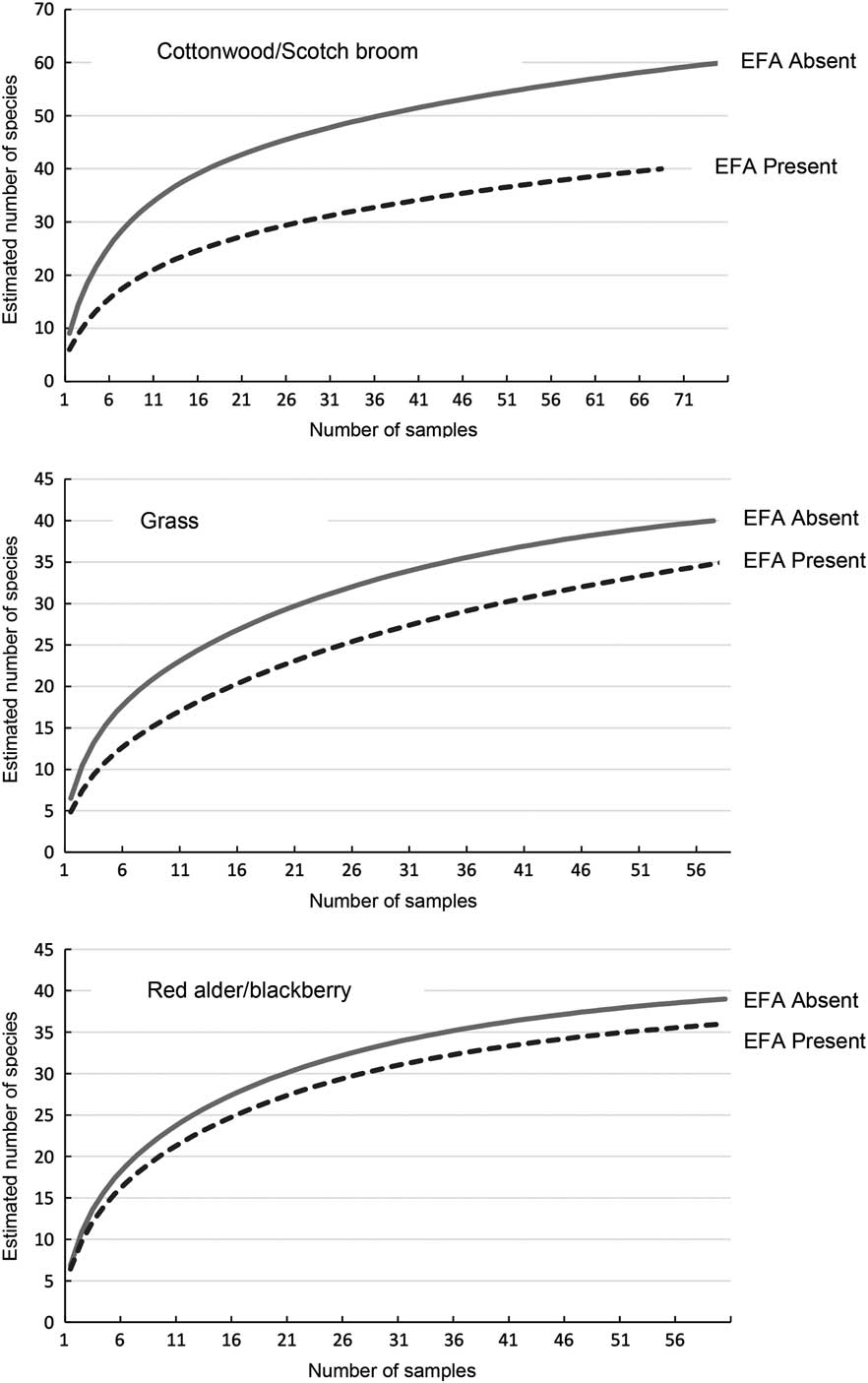

Plots of smoothened species richness estimates versus number of samples (pitfall traps) show curves approaching a plateau for all three plant zones (Fig. 2). This supports the adequacy of the sampling protocol with respect to estimates of species richness and thus biodiversity.

Fig. 2 Smoothened (100 runs) species accumulation curves for the arthropods captured in pitfall traps in areas with the European fire ant (EFA) and EFA-free areas of three plant communities. Curves reaching a plateau suggest that sampling has been adequate to make reasonable estimates, and comparisons, of species richness and biodiversity.

The pitfall traps captured a total of 79 arthropod species at least once, including the 13 ant species, 21 beetle (Coleoptera) species and 21 species of spider (Araneae). There were also nine Hemiptera species; two Lepidoptera caterpillars; two springtail (Collembola) species; one species each of wingless wasp (Hymenoptera), earwig (Dermaptera), and Diplura; two species of millipedes (Diplopoda); one centipede (Chilopoda) species; two Isopoda; two species of harvestman (Opiliones); and one type of mite (Acari).

The total capture numbers of members of the most common taxa of non-ants are shown in Table 2. Twenty taxa were caught at significantly different numbers in EFA-infested versus un-infested areas; 17 of those represented declines where EFA was present.

Table 2 Total numbers of non-insect arthropods captured in pitfall traps.

Notes: Data are organised by order or family and include only those species for which five or more individuals were captured. Asterisk denotes significantly different values between areas with or without the EFA (χ2 test; Bonferoni correction for multiple comparisons).

EFA, European fire ant.

Biodiversity of ground-dwelling arthropods, as measured by pitfall traps, was consistently lower in EFA-infested zones than those free of the ants (Table 3). These differences are absent when ants are excluded from the data (Table 4).

Table 3 Biodiversity indexes (±SD) for all pitfall-trapped arthropod species in plant communities with or without the EFA.

Notes: EFA–non-EFA pairs marked by an * are significantly different (by non-overlap of 95% confidence intervals; calculated as 1.96×SD). No determination of significant differences are made for Shannon and Simpson Inverse biodiversity estimates because they were calculated without measures of SD.

SD, standard deviation; EFA, European fire ant.

Table 4 Biodiversity indexes (±SD) of non-ant, ground-dwelling arthropods captured by pitfall traps in plant communities with or without the EFA.

SD, standard deviation; EFA, European fire ant.

Discussion

The EFA in this study have had the effects of a typical invasive ant, unusual for a temperate species. In Wittman’s (Reference Wilson2014) tabulation of literature on invasive ants, 22 of 24 papers quantified the effects of tropical or subtropical invasives on resident ants but there were only two reports of species with temperate origins. Typical effects of invasive ants have been declines in the number and abundance of native ant species. For example, Human and Gordon (Reference Human and Gordon1997) observed the complete replacement of three native ant species by the Argentine ant (L. humile) over a four-year period. Invasive ant species have even been reported to displace previously invasive ants, as in cases of P. megacephala displacing L. humile, S. invicta Buren, and S. geminata (Fabricius) (reviewed in Erickson Reference Erickson1971). The results of the current study clearly show that where the EFA (M. rubra) has established, other ant species are almost completely absent. This result was most apparent in a cottonwood/Scotch broom community, which had the greatest ant diversity in the absence of the invader (Fig. 1).

Few species of ants were collected in the EFA-free grassy zone (Fig. 1) but the two most common species there are congenerics (M. incompleta and M. specioides), and likely to be competitors. Both were absent in the grassy areas with the EFA, suggesting that they were displaced by the new invader. Holway et al. (Reference Holway, Lach, Suarex, Tsusui and Case2002), in their review of the causes and consequences of invasive ants, suggested that invasive ants may have the greatest effect on ecologically similar species.

Few ants of any species were collected in the EFA-free red alder/blackberry areas (Fig. 1), suggesting that ants have not been successful at exploiting this habitat. In general, the ground in these areas is cool, shaded, and damp, not conducive to thermophilic ants. Interestingly, the EFA was collected in large numbers in the same type of plant community, and nests or bivouacs were commonly encountered in the leaf litter. It is not clear why the EFA is able to produce such high population densities when other ant species do not. They may be present because of population pressure in nearby cottonwood/Scotch broom and grassy areas, they may be exploiting a resource that pre-existing species have not accessed, or they may be more cool tolerant.

The abundance of the EFA in the infested areas (Table 1), as measured by pitfall trap catches, far exceeded the total numbers of ants of all types collected in the unaffected areas. Such superabundance has also been reported for other invasive species (Porter and Savignano Reference Porter and Savignano1990; Holway Reference Holway1998), and may be due to escape from the natural enemies of their home range, and re-allocation of resources to worker production instead of fighting neighbouring colonies (which would contain genetically similar individuals). This result may also be the result of disturbed habitats or other environmental factors that favour the EFA.

Holway et al. (Reference Holway, Lach, Suarex, Tsusui and Case2002) reviewed the causes and consequences of ant invasions and identified a number of features that are common to the more cosmopolitan invasive species. They are phylogenetically and morphologically diverse but most are tropical or subtropical, and have successfully established only in similar climates, except where established indoors. The EFA is thus unusual in being a temperate species that shows the properties of a typical invasive species in other temperate regions. There is a strong tendency for invasive ant species to form large, multiple-queened, multiple-nested supercolonies. That is certainly the case for the EFA in British Columbia. Nests are often as little as a metre apart and there is little apparent negative interaction between workers from adjoining nests (personal observation). Garnas et al. (Reference Garnas, Drummond and Groden2007) however, reported that M. rubra populations on Mount Desert Island, Maine, United States of America are not truly unicolonial, as intercolony aggression is present both within and between local infestations. Further, invasive ants usually have an omnivorous diet, and the EFA does harvest honeydew from aphids as well as preying on small invertebrates. They were not observed to collect elaiosomes in this study but this was not specifically investigated.

Holway et al. (Reference Holway, Lach, Suarex, Tsusui and Case2002) give a thorough review of the competitive mechanisms and behaviours reported to be important in interactions between invasive ant and native ants, including interspecific aggression. Few incidences of aggression between EFA workers and those of other species were observed during this study but few contacts were seen. In one notable example, workers of the large carpenter ant Camponotus modoc Wheeler were seen to be attacking EFA workers as an EFA column passed by an entrance to the carpenter ant nest. A pile of dead EFA workers had accumulated and no C. modoc workers were seen to be killed, however one week later, no carpenter ants were observed at the same location.

In this study, one of the species present only when M. rubra was absent is another exotic, M. specioides (Fig. 1). Its native range extends from Spain to western Russia and from southern Finland to Italy and the Balkans (Collingwood Reference Collingwood1979). It was first recorded in North America in Washington State by Jansen and Radchenko (Reference Jansen and Radchenko2009) who reported that it possesses the characteristics of a potential pest ant, e.g., high aggressiveness, polygyny, and tendency to reach high local abundance. Myrmica specioides has likely been established in southwestern British Columbia for some years but, aside from some reports of stinging, has not created much of a stir in the public.

Because this study was observational, not experimental, we cannot say that the EFA directly caused differences in the abundance of other species. However, the species accumulation curves (Fig. 2) suggest that sampling was adequate to make comparisons between areas with the EFA and control areas that were EFA-free, and several taxa of non-ant arthropods were less frequently captured in areas with EFA. Some inequalities could be attributable to non-ant differences between study areas but the fact that 17 out of 20 significant differences showed fewer individuals in the EFA areas, does suggest an ant effect (Table 2). Carabidae (Coleoptera) and Staphylinidae (Coleoptera), centipedes, spiders, and harvestmen (Opilionids) are predators and may lose out in direct competition with the ants. Predominantly herbivorous groups such as weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) and millipedes were not significantly reduced. Predominantly herbivorous Coleoptera of the families Elateridae and Tenebrionidae were sometimes reduced. The high capture rates of Isopoda (generally scavengers) in all size categories, suggests that they were not heavily preyed upon by the ants. Their capture rates were lower than controls in some EFA-infested communities but were higher in others, suggesting little relationship to the presence of the EFA.

In this study, the presence of established populations of the EFA was associated with a reduced overall arthropod diversity. Although there was a reduction in the numbers of individuals of certain non-ant taxa, much of the loss of biodiversity can be attributed to the impact on other ant species.

The results of this study suggest that the recently established population of M. rubra in southwestern British Columbia represents a rare example of a temperate ant that shows the characteristics of an invasive species. Much work remains to be done to understand the causes for the competitive success of newly established populations of the EFA, and to relate these to other invasive ant species.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank to Sue Seward and Emerald Naumann for assistance in the field, handling specimens, and formatting. The following organisations and individuals gave permission to carry out the work on lands that they administer: the city of Vancouver, Sophie Dessureault; city of Richmond, Lesley Douglas, Eric Portelance; Greater Vancouver Regional District, Markus Merkens; and the Canadian Wildlife Service (for the Sea Island Conservation Area), Courteney Albert. Andre Francoeur gave advice on the determination of M. specioides. This work was supported in part through funds from the Langara College Research Committee and Langara College Professional Development funds. Nadine Beaulieu translated the abstract. They also thank to the anonymous referees who improved the manuscript.